Every city has a history woven with tales of development, struggle, and occasionally, disaster. Halifax, a quiet, picturesque town in Canada, harbors one such tragic event deep within its past: The Halifax Explosion. A catastrophe that rocked not only the city, but also the world, with its extent and consequences. The incident marked a devastating day in human history.

The Cause: A Collision that Sealed the Fate

The morning of December 6, 1917, started like any other for the residents of Halifax, Nova Scotia, until the calm was shattered by a catastrophic event. The cause? A disastrous collision in the Halifax Harbor between two ships: The SS Mont-Blanc, a French cargo ship loaded with wartime explosives, and the SS Imo, a Norwegian vessel.

The Mont-Blanc was fully loaded with a deadly cocktail of explosives, including TNT, picric acid, guncotton, and benzol, intended for the war efforts in Europe during World War I. The Imo, running late and moving at a high speed, collided with the Mont-Blanc in the narrowest part of the harbor, setting off a spark that ignited the benzol stored on the deck of the Mont-Blanc.

The crew of the Mont-Blanc, realizing the inevitable catastrophic consequence, abandoned the ship and fled to the nearby shores, warning as many people as they could. But the imminent disaster was not understood by many, and curious onlookers gathered to watch the spectacle of the burning ship.

Approximately 20 minutes later, the unthinkable happened: the burning Mont-Blanc exploded.

The Explosion: Catastrophe Unleashed

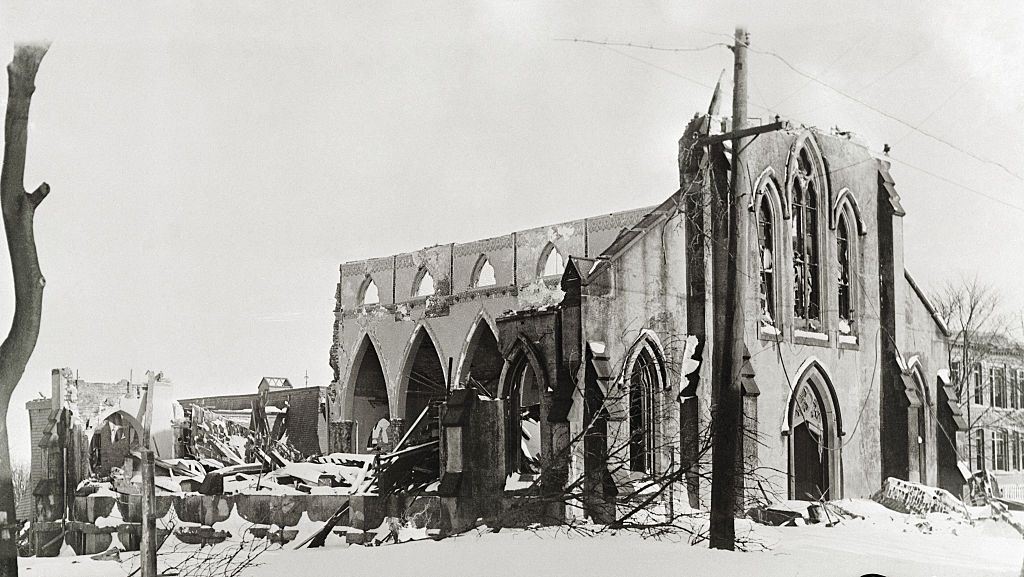

The Halifax explosion was the largest man-made explosion before the advent of nuclear weapons, releasing energy equivalent to about 2.9 kilotons of TNT. The blast wave radiated across the harbor and the city, instantly flattening over 2 square kilometers of the city, reducing buildings, homes, factories, and ships to rubble.

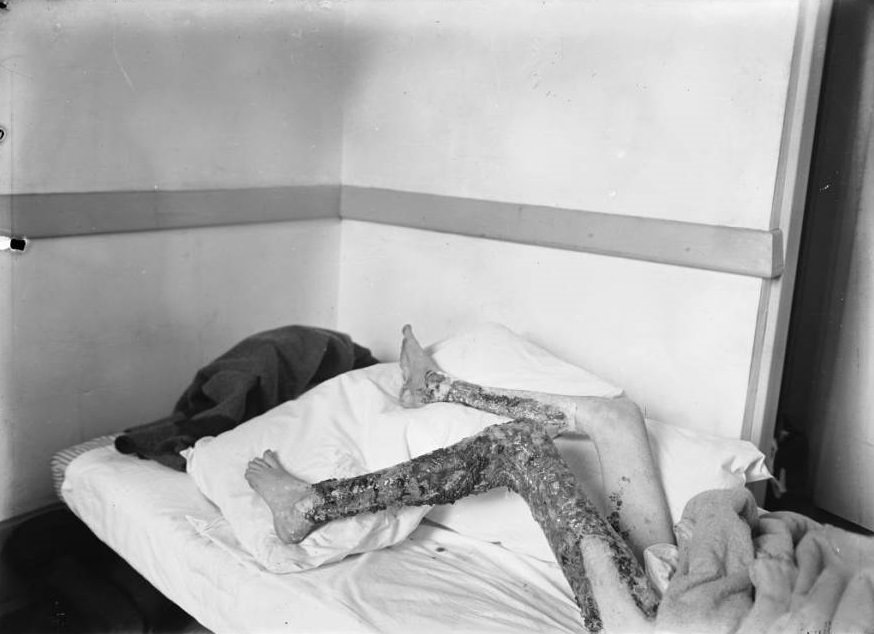

The casualties were unprecedented. More than 1,900 people were instantly killed, and an estimated 9,000 were injured, many severely. Approximately 25,000 residents, almost half of Halifax’s population, were left without adequate shelter. Additionally, a tsunami created by the explosion wiped out Mi’kmaq First Nation people who had lived in the Tufts Cove area for generations.

Aftermath: Rising from the Ashes

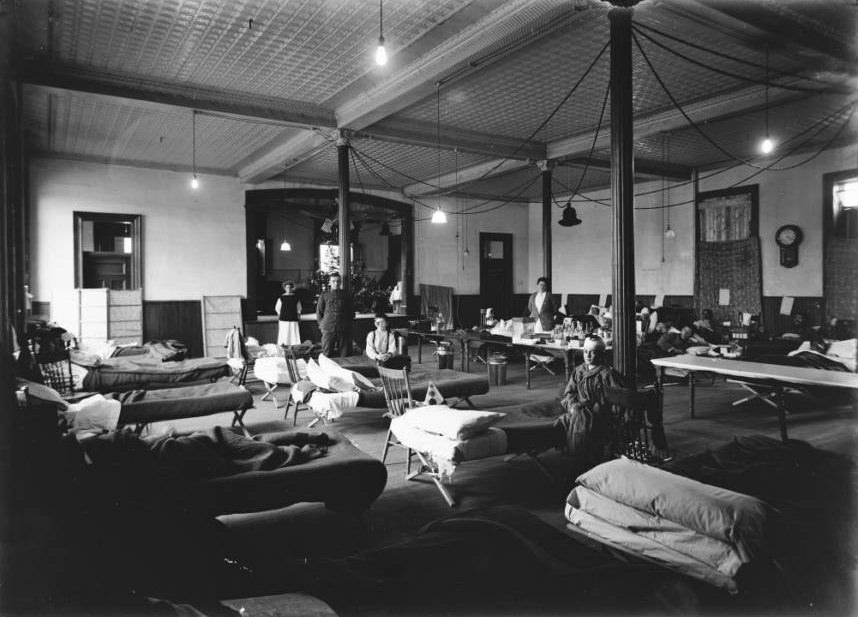

In the aftermath of the explosion, Halifax was a city in ruins. But amidst the tragedy, stories of resilience, heroism, and humanity emerged. Rescue teams, medical personnel, and volunteers from across Nova Scotia and neighboring provinces and states rushed to provide relief.

Telegraph operator Vince Coleman, realizing the impending disaster, chose to stay behind to warn an incoming passenger train, saving countless lives, but losing his own in the process. His story is just one of the many tales of bravery that day.

In the years that followed, Halifax faced the monumental task of rebuilding. Reconstruction efforts were funded by Canadian government assistance and international aid, including a significant donation from Boston, which sends a Christmas tree to Halifax each year to this day as a symbol of their continued friendship.

The city gradually reconstructed itself, rebuilding structures, communities, and lives, transforming the scarred cityscape into a vibrant and bustling city once again. Today, the Halifax Explosion is remembered through various memorials scattered around the city, and the incident remains a significant part of the city’s rich history.

Here are some rare historical photographs that depict the intensity and the aftermath of the Halifax Explosion.

Two ships collided at one knot, igniting a shipment of benzol barrels. Over 800 meters away, the explosions cause a pressure wave that snaps trees and bends iron for kilometers. As a result, a water void in the bay created a tsunami wave that destroyed Halifax.

There was a record set for the longest distance flown by a living human projectile during the Halifax explosion: One man, William Becker, was lucky: He was in a rowboat 300 feet from the ship when it exploded, which sent him 1,600 yards across the harbor. He swam to safety and lived until 1969.

My mom’s elementary school teacher survived the explosion but lost an eye to a shard of glass. To freak out the children, she would remove her glass eye whenever they misbehaved.

At the mueseum, they have some of the clothes of people that died on display. That was quite a sad thing to see.

SS Imo, one of the two ships directly involved in the eruption, was launched in 1889 under the name Runic for the White Star Line (which later built Titanic, Britannic, and Olympic). The ship collided with the Mont Blanc, which was carrying explosives. After the collision, the MB ignited and exploded. The Runic had changed owners and names many times by the time of the Halifax Explosion, eventually becoming the South Pacific Whaling Company. The ship was named Ino at the time of the explosion, and was later renamed Guvernøren in 1920. In 1921, she ran aground off the Falklands and was abandoned.