In the history of aviation, certain aircraft captivate one’s imagination with their cutting-edge design and promise, even if they never reach full operational status. The Northrop XB-35, an experimental heavy bomber developed during World War II, is one such marvel.

Dreaming of Innovation: The XB-35 Genesis

As World War II raged, the United States sought to bolster its military prowess and global strategic reach. Central to this was the ability to deploy long-range bombers capable of carrying heavy payloads to distant targets. The Northrop Corporation, founded by the visionary Jack Northrop, responded to this call to arms with the conception of the XB-35, an aircraft that promised unparalleled range and payload capabilities, thanks in part to its radical ‘flying wing’ design.

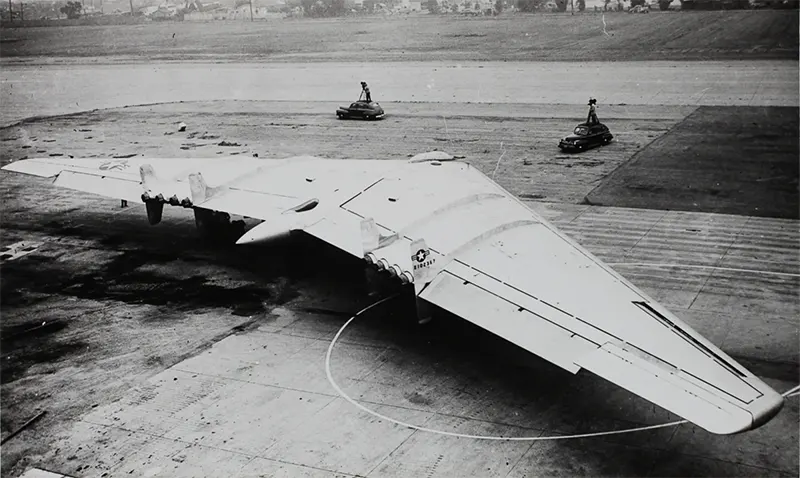

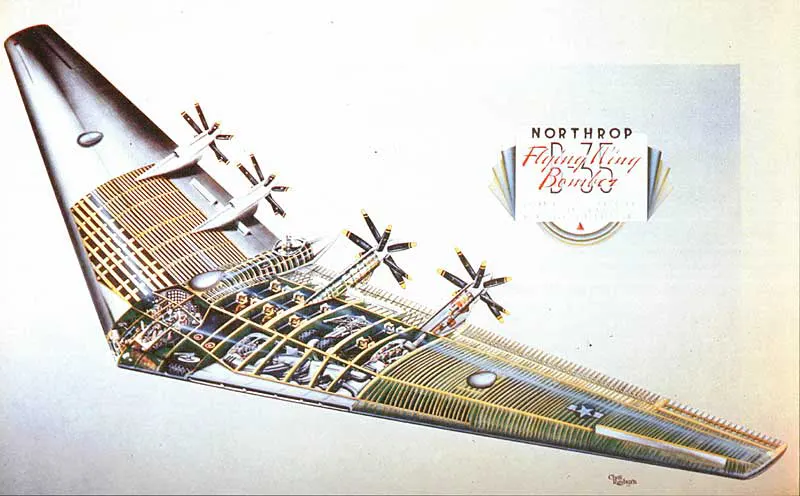

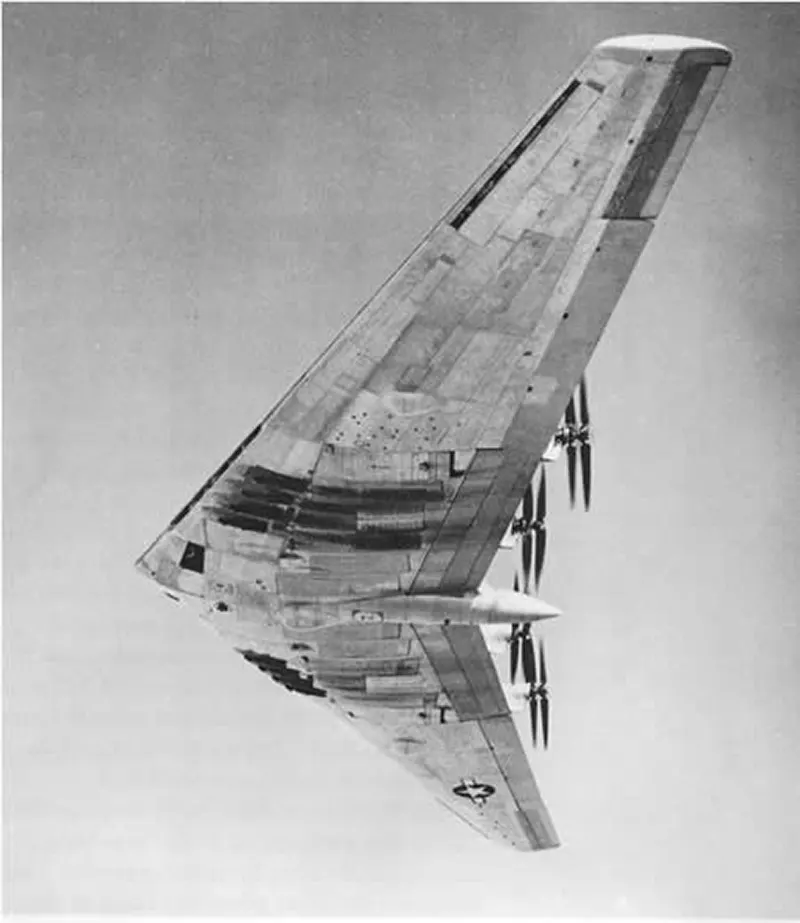

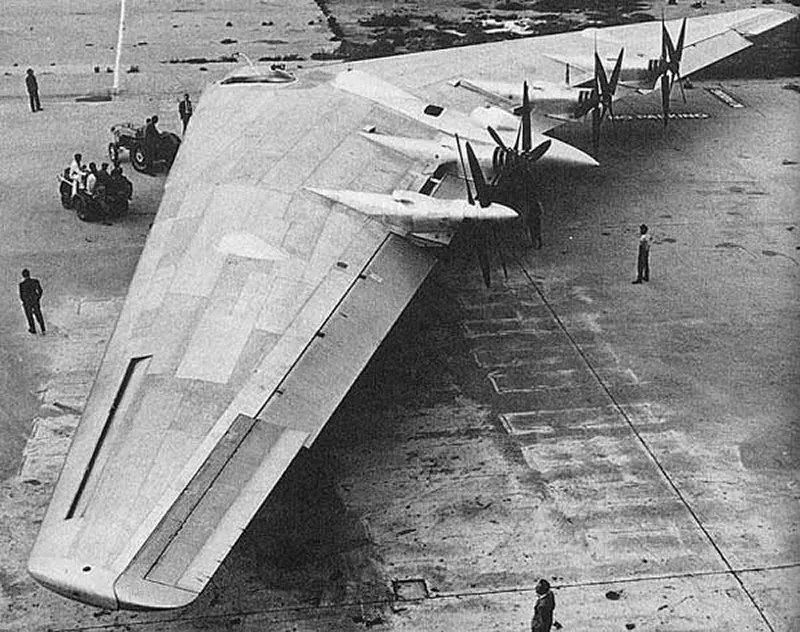

The flying wing, characterized by the absence of a conventional fuselage and tail, wasn’t a new concept, but never before had it been proposed on such an ambitious scale. This design aimed to reduce drag significantly, thus enhancing the aircraft’s range and fuel efficiency. It was a daring departure from traditional aeronautical design, illustrating the extremes of innovation that the pressures of war brought to the fore.

From Drawing Boards to the Skies: The Design and Challenges

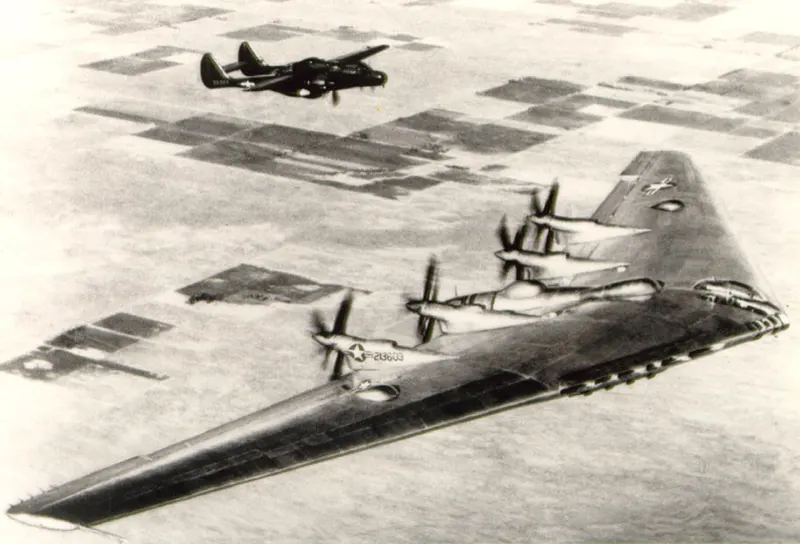

The XB-35 was a behemoth, with a wingspan comparable to a B-29 Superfortress. Its all-wing structure was intended to house four contra-rotating propellers (pusher configuration), powered by massive Pratt & Whitney R-4360 ‘Wasp Major’ radial engines. These engines were the pinnacle of piston engine technology, a necessary choice when jet propulsion was still in its infancy.

However, translating groundbreaking design into a functional aircraft presented monumental challenges. The XB-35 suffered from a range of issues, including problems with propeller synchronization and engine reliability, structural inefficiencies, and a host of other developmental setbacks. These were complicated further by the rapidly evolving landscape of aeronautical engineering, with jet technology promising to outdate the XB-35 before it even took to the skies.

First Flight and Operational Struggles

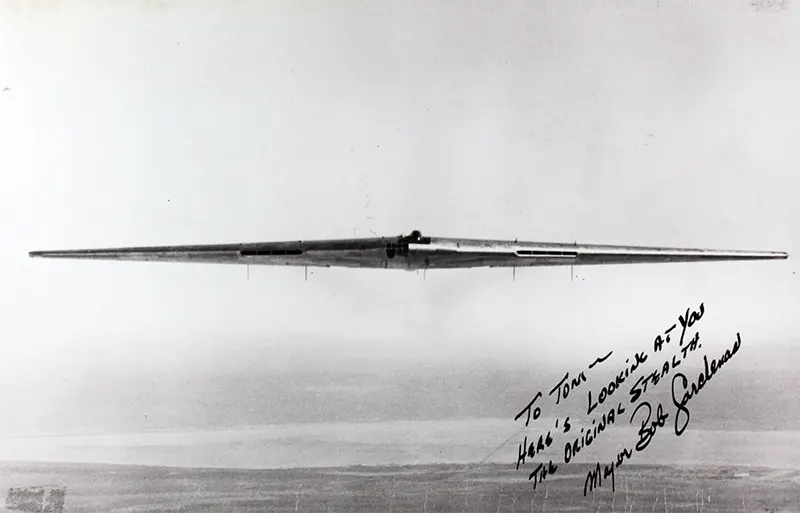

After years of developmental challenges, the XB-35 finally took its maiden flight in 1946, a post-war era that had already begun to erode the strategic necessities that birthed the project. While the aircraft’s performance metrics, including its range and payload, were promising, it became increasingly apparent that the XB-35 was a machine born out of time. The complexities of its maintenance, paired with the teething troubles of its advanced systems, led to spiraling costs and diminishing faith in the project.

With the advent of more reliable and powerful jet-powered bombers, particularly the B-47 and B-52, the XB-35’s operational role became increasingly questionable. The piston-engined giant, despite the futuristic promise, was competing against the undeniable momentum of jet-powered aviation.

The XB-35 project was eventually canceled, with only a handful of prototypes ever taking to the skies. However, its legacy is not measured by its operational history but by its audacious design and the glimpse it offered into the future of aviation. Jack Northrop’s flying wing concept was revolutionary, and its aerodynamic principles were sound, aspects that found vindication decades later in designs such as the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.