For centuries, the term “computer” meant a person, often a woman, performing complex calculations by hand. These human computers were essential in many fields, from astronomy to engineering, long before electronic computers existed. By the late 19th century, these women became the unsung heroes of numerous scientific advancements.

In the early 20th century, human computers were crucial in various industries. Teams of people were used to undertake long and often tedious calculations. The work was divided so it could be done in parallel, and the same calculations were frequently performed independently by separate teams to ensure accuracy. This method was efficient and ensured high-quality results.

Pioneers of Computing

Ada Lovelace

One of the earliest known female computer pioneers was Ada Lovelace. Born in 1815, she was an English Countess and a brilliant mathematician. She is often hailed as the world’s first computer programmer. Ada foresaw the potential of machines beyond simple arithmetic, planting the seeds for modern computing. Her work laid the groundwork for future generations of human computers.

Grace Hopper

Another notable figure was Grace Hopper, a visionary in computer science. She developed the first compiler, a tool that revolutionized programming by converting human-readable code into machine language. Hopper’s innovation made it possible for computers to understand and execute complex instructions more easily.

Hedy Lamarr

Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr also made significant contributions to early technology. Renowned for her beauty, she co-invented a frequency-hopping technology that became the backbone of today’s Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. Her invention was initially aimed at preventing torpedo signals from being jammed during World War II.

Katherine Johnson

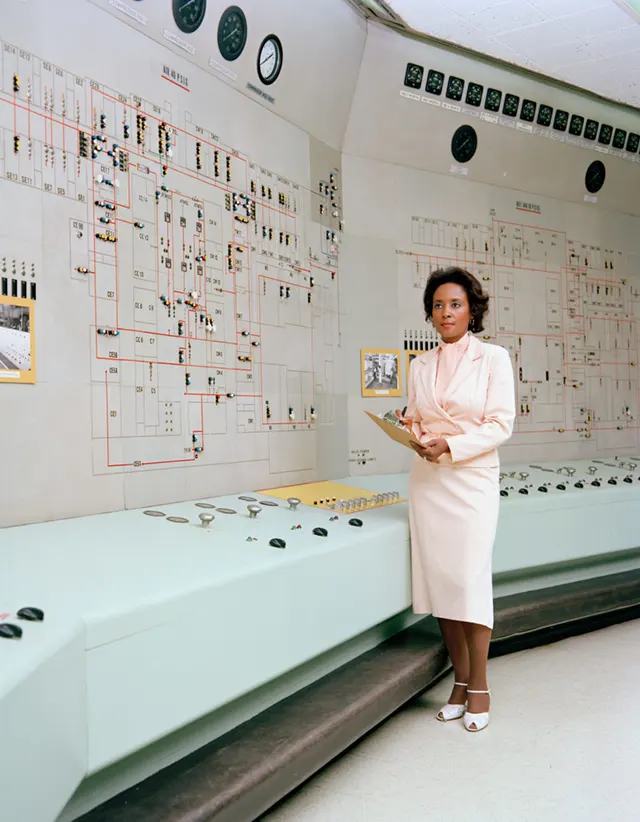

Katherine Johnson, an African-American mathematician, is another inspiring figure. Her precise calculations were vital for the success of U.S. space missions, including John Glenn’s orbit around the Earth and the Apollo moon landing. Johnson’s work was critical to NASA’s success during the Space Race..

Read more

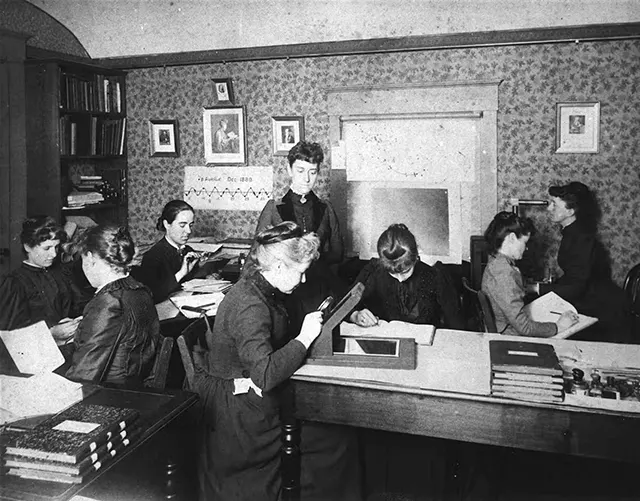

Edward Pickering and the Harvard Computers

In the late 19th century, Edward Pickering of the Harvard Observatory hired a team of women. Frustrated with his male assistants’ performance, he recognized that women could do the job as well as men and often worked for less pay. These women, sometimes referred to as “Pickering’s harem” or the Harvard Computers, undertook clerical work deemed tedious by their male counterparts. Despite their lower wages, they made significant contributions to astronomy. They cataloged around ten thousand stars, discovered the Horsehead Nebula, and developed a system to classify stars. Among them, Annie Jump Cannon stood out, capable of classifying stars at an impressive rate of three per minute.

Human Computers During World War I

During World War I, Karl Pearson and his Biometrics Lab were instrumental in producing ballistics calculations for the British Ministry of Munitions. Among his team, Beatrice Cave-Browne-Cave played a key role in calculating shell trajectories. In 1916, she left Pearson’s employ to work full-time for the Ministry. In the United States, women computers were hired in 1918 to calculate ballistics, working in a building on the Washington Mall. Elizabeth Webb Wilson served as the chief computer, overseeing these crucial calculations.

In the early 1920s, George Snedecor, a professor at Iowa State College, sought to enhance the school’s science and engineering departments. He experimented with new punch-card machines and calculators while also collaborating with human calculators, most of whom were women. Among them was Mary Clem, who introduced the term “zero check” to identify calculation errors.

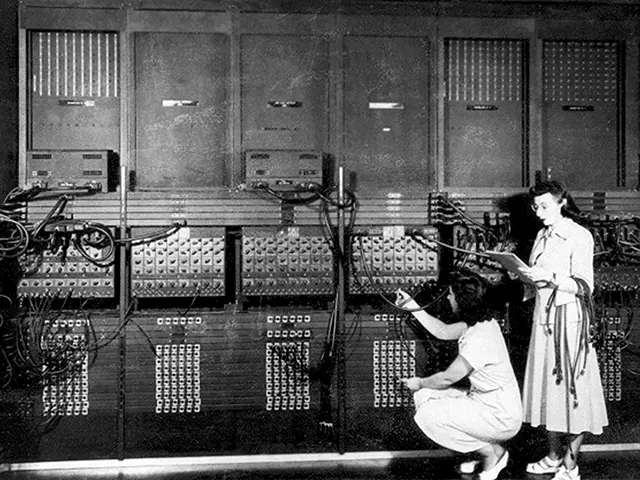

The “Kilogirl” Concept in the 1940s

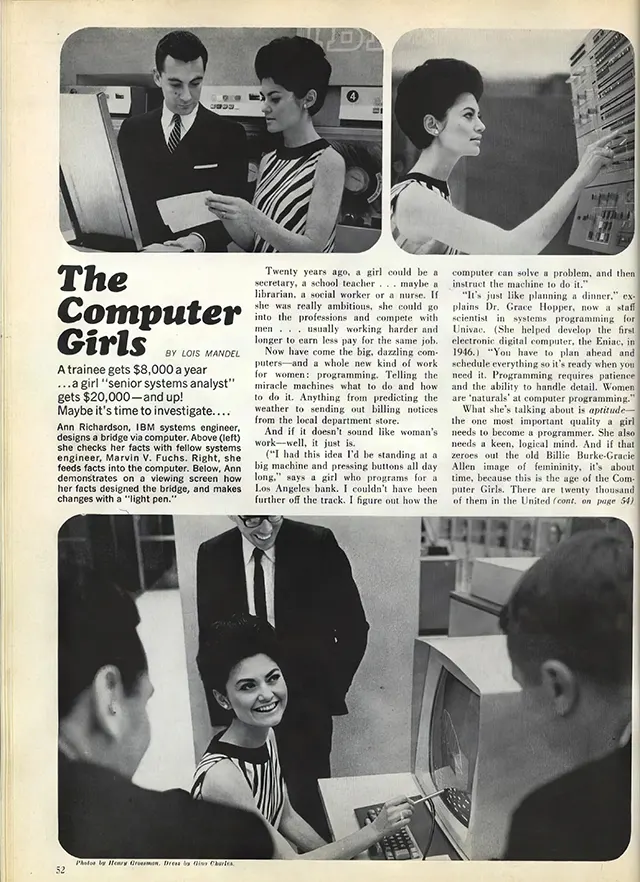

By the 1940s, computing and calculating were considered “women’s work.” A member of the Applied Mathematics Panel even created the term “kilogirl” to represent approximately a thousand hours of computing labor. Although the media celebrated women’s contributions to the U.S. war effort during World War II, their roles were often downplayed. The complexity, skill, and knowledge required for computing work were minimized, portraying these tasks as simple clerical work. During World War II, women performed the majority of ballistics computing, a task male engineers deemed beneath their expertise. Black women worked just as hard, often twice as hard, as their white counterparts but did so in segregated environments.

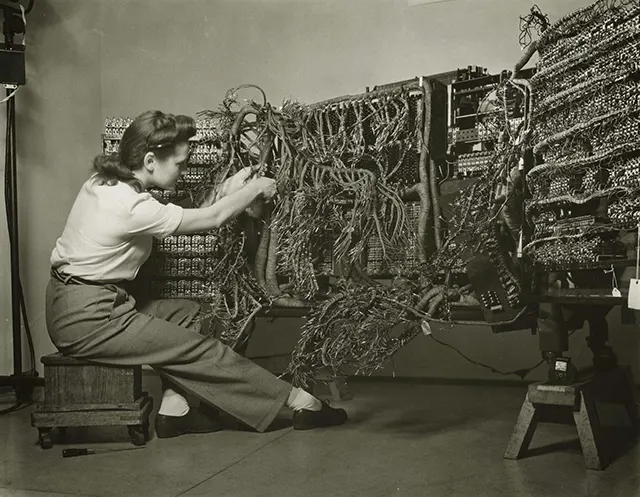

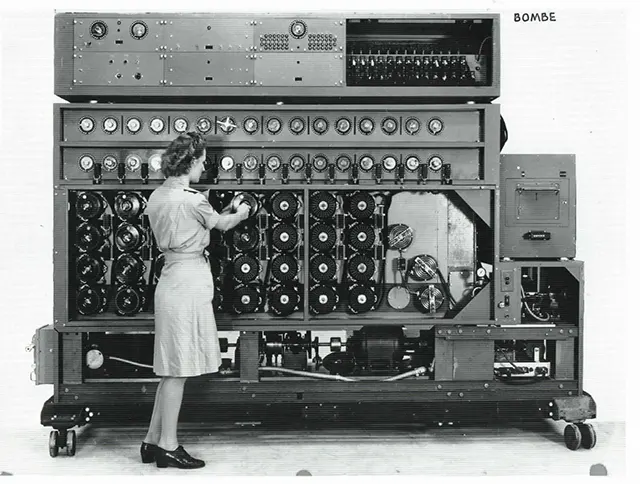

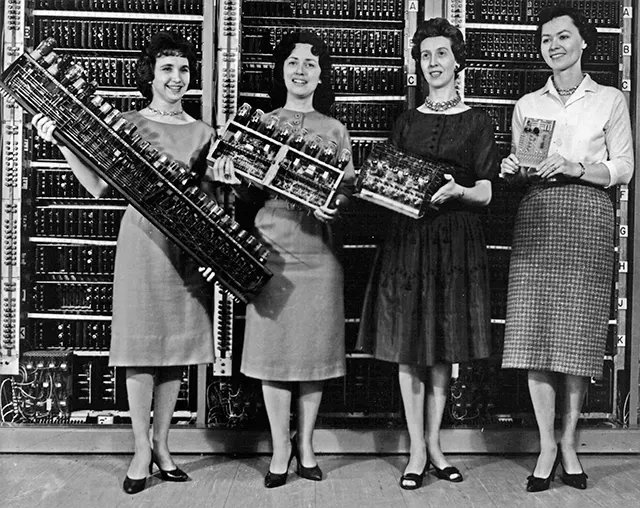

Women in Cryptography During World War II

By 1943, nearly all human computers were women. One report noted, “Programming requires lots of patience, persistence, and a capacity for detail, traits that many girls have.” Women played a significant role in cryptography during World War II, with many eventually operating and working on the Bombe machines despite initial resistance. Joyce Aylard was one such operator, testing various methods to break the Enigma code. Joan Clarke, a cryptographer, collaborated closely with her friend Alan Turing on the Enigma machine at Bletchley Park. Despite her promotion to a higher salary grade, civil service lacked a designation for a “senior female cryptanalyst,” so she was listed as a linguist instead.

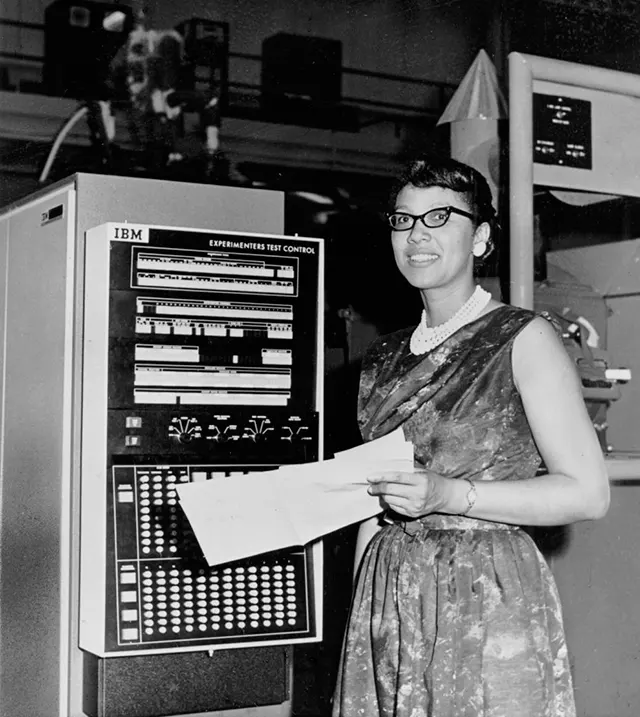

Post-War Recruitment by NACA and NASA

Following World War II, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and later NASA recruited women as human computers. By the 1950s, a team of female mathematicians was performing critical calculations at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. This team included notable figures such as Annie Easley, Katherine Johnson, and Kathryn Peddrew. At the National Bureau of Standards, Margaret R. Fox joined the technical staff of the Electronic Computer Laboratory in 1951. In 1956, Gladys West was hired by the U.S. Naval Weapons Laboratory as a human computer. Her work was instrumental in the calculations that eventually led to the development of GPS technology.

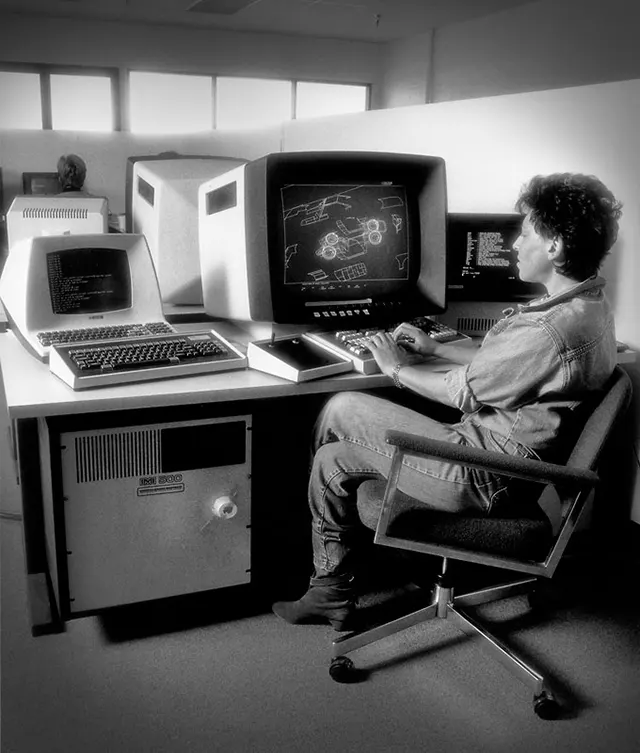

At Convair Aircraft Corporation, Joyce Currie Little was among the original programmers analyzing data from wind tunnels. She used punch cards on an IBM 650, which was located in a different building from the wind tunnel. To expedite the delivery of the punch cards, she and her colleague, Maggie DeCaro, used roller skates to travel between buildings more quickly.

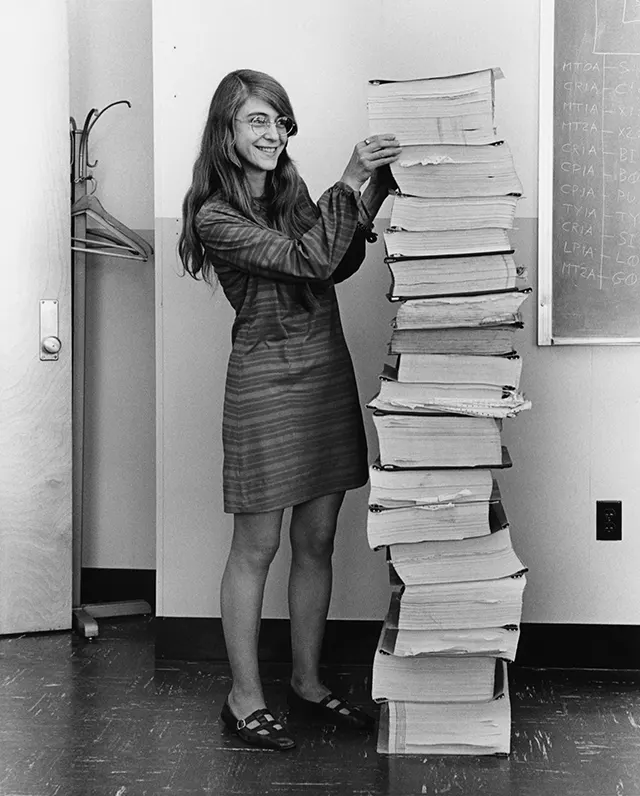

Milly Koss, who had worked with Grace Hopper at UNIVAC, joined Control Data Corporation (CDC) in 1965. There, she developed algorithms for graphics, including methods for graphic storage and retrieval. Between 1961 and 1963, Margaret Hamilton began studying software reliability while working on the U.S. SAGE air defense system. In 1965, she was responsible for programming the onboard flight software for the Apollo mission computers. Once Hamilton completed the program, the code was sent to Raytheon, where “expert seamstresses” known as the “Little Old Ladies” hardwired the code by threading copper wire through magnetic rings.

In 1942, NACA acknowledged that “the engineers admit themselves that the girl computers do the work more rapidly and accurately than they could.” These women, often working in the shadows, were the backbone of many technological advancements. Their contributions laid the foundation for the computer age and paved the way for future generations of women in technology.