Television gained a foothold in the United States during and following the Second World War. As TV sales boomed in the 1950s, they became America’s most popular entertainment source. Approximately 20 percent of American homes had TVs in 1950. Nearly 90 percent of homes in ten years had TVs – some even had color TVs. As a result of this growing demand, the number of TV stations, channels, and programs increased.

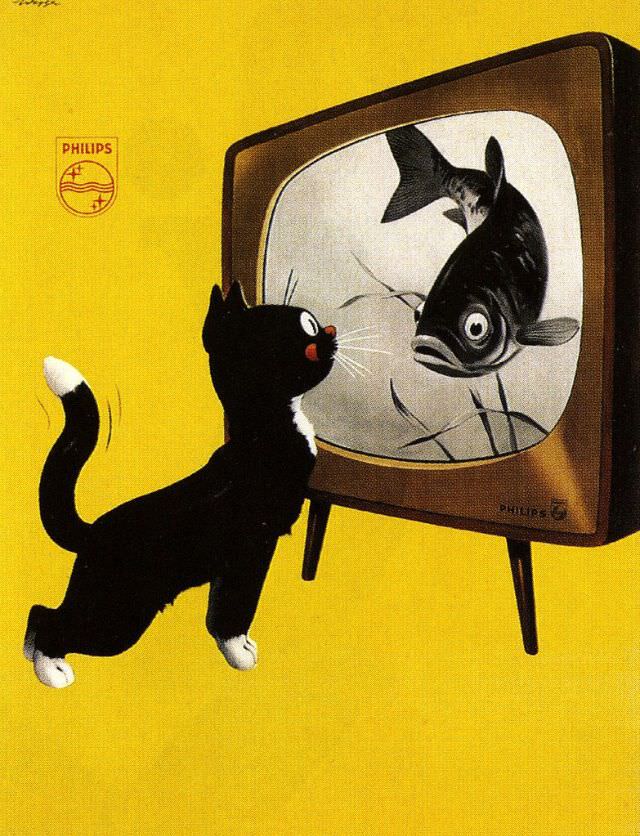

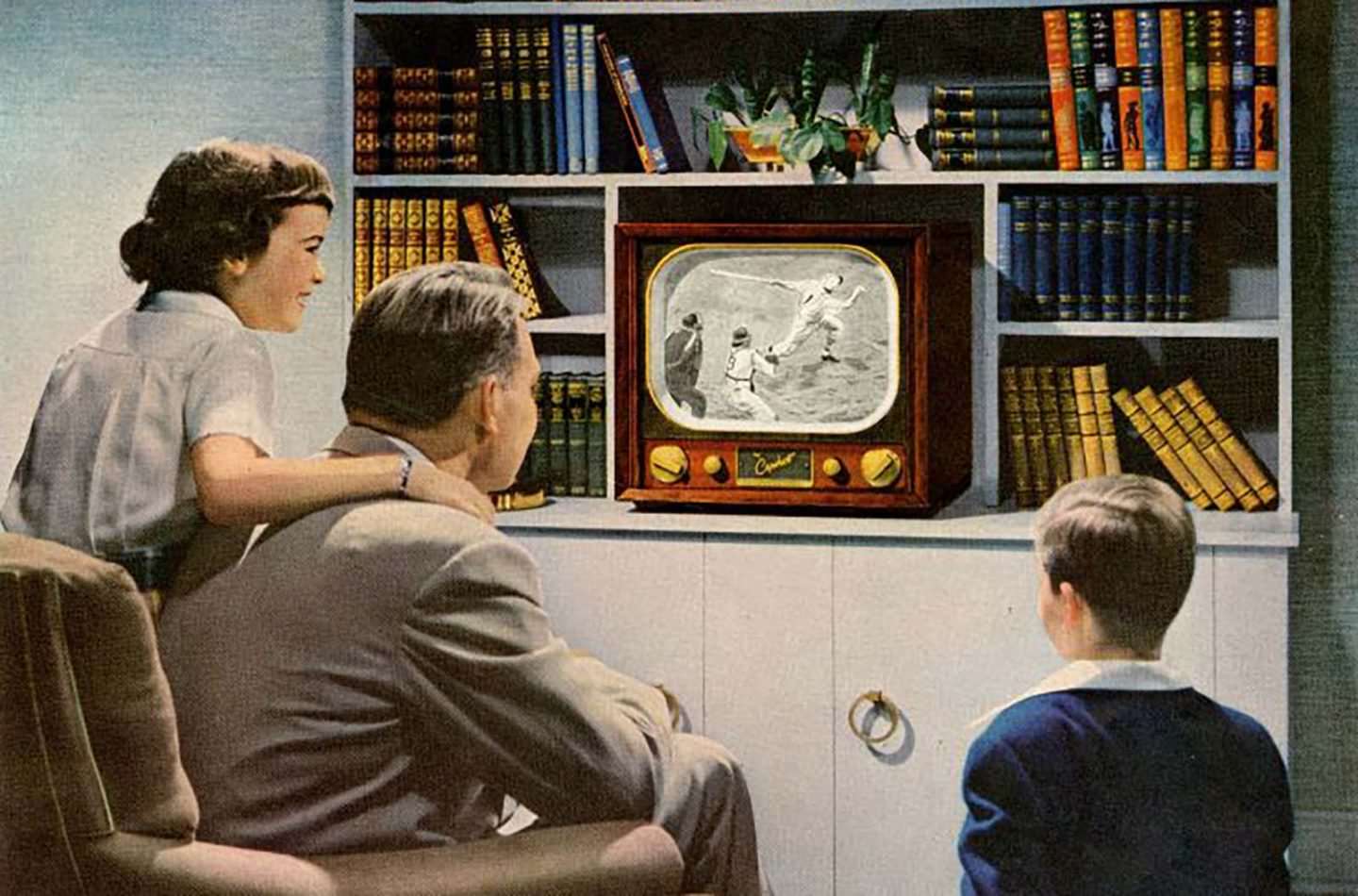

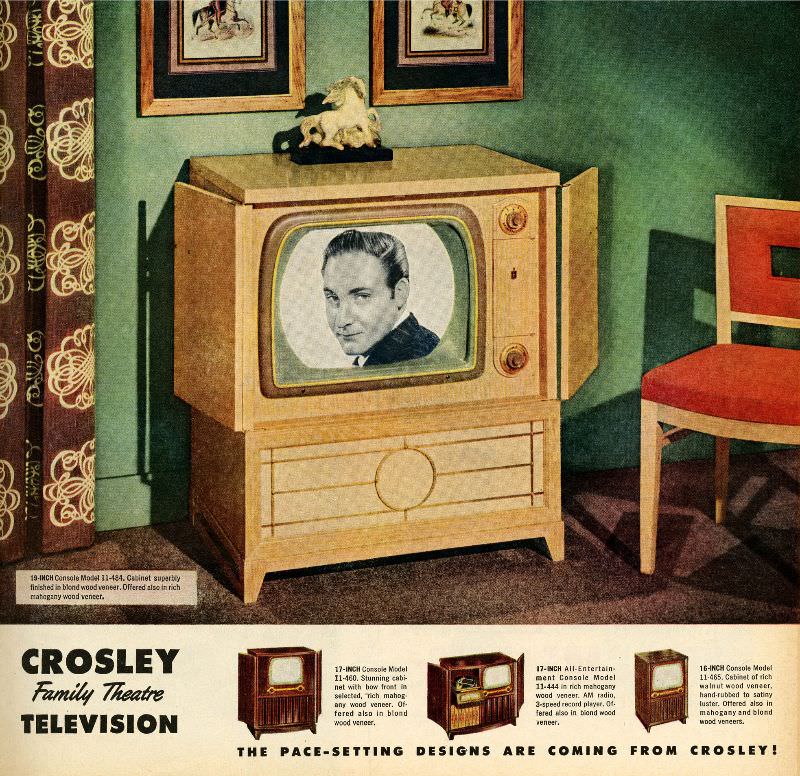

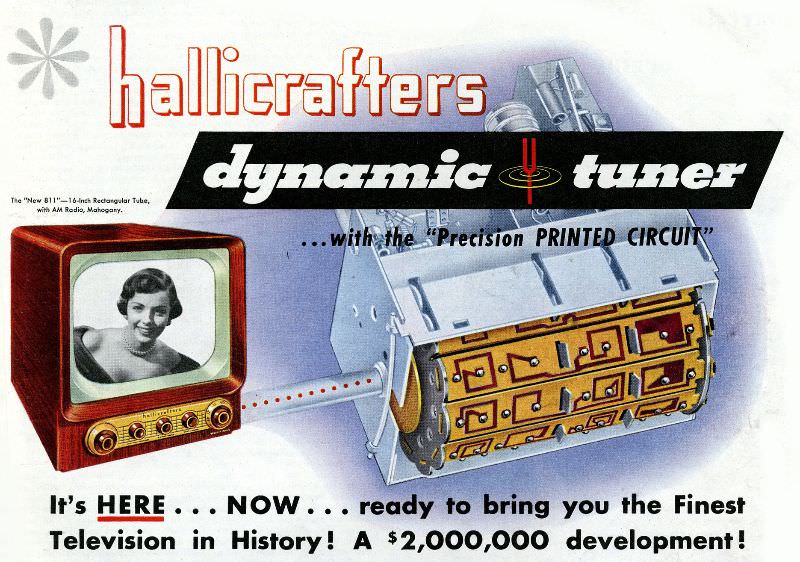

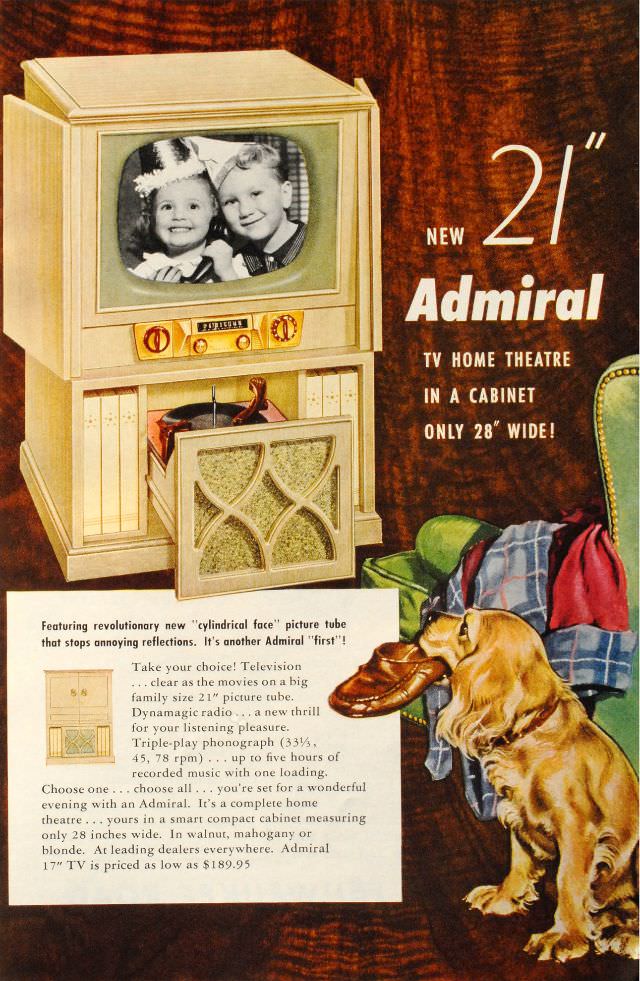

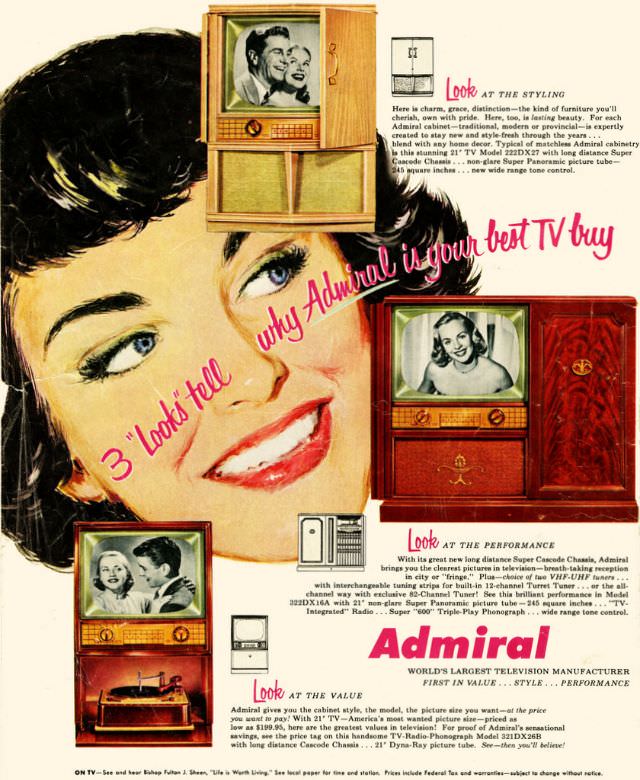

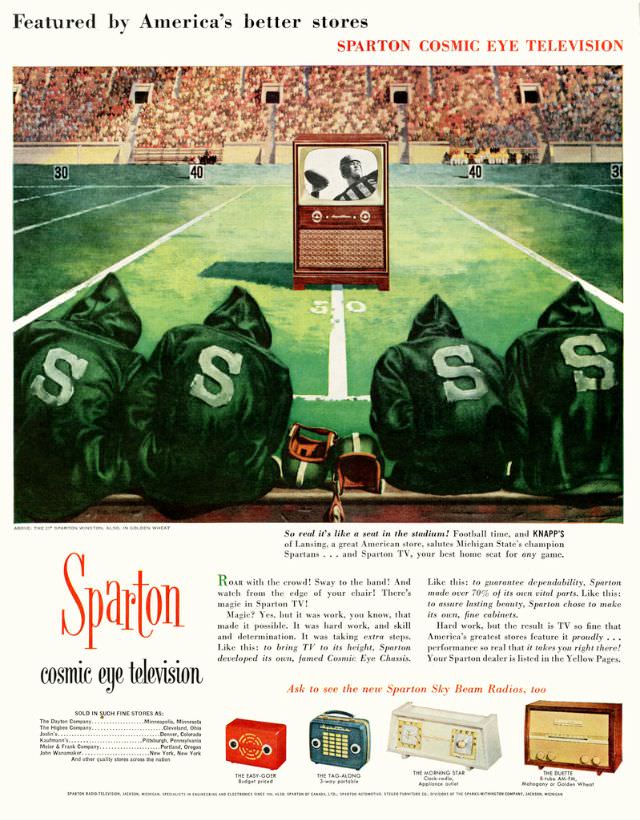

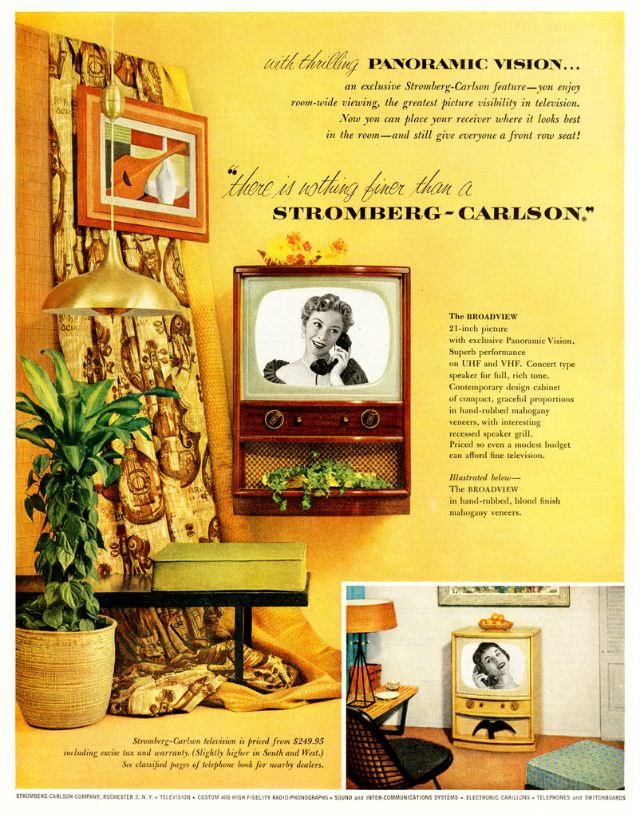

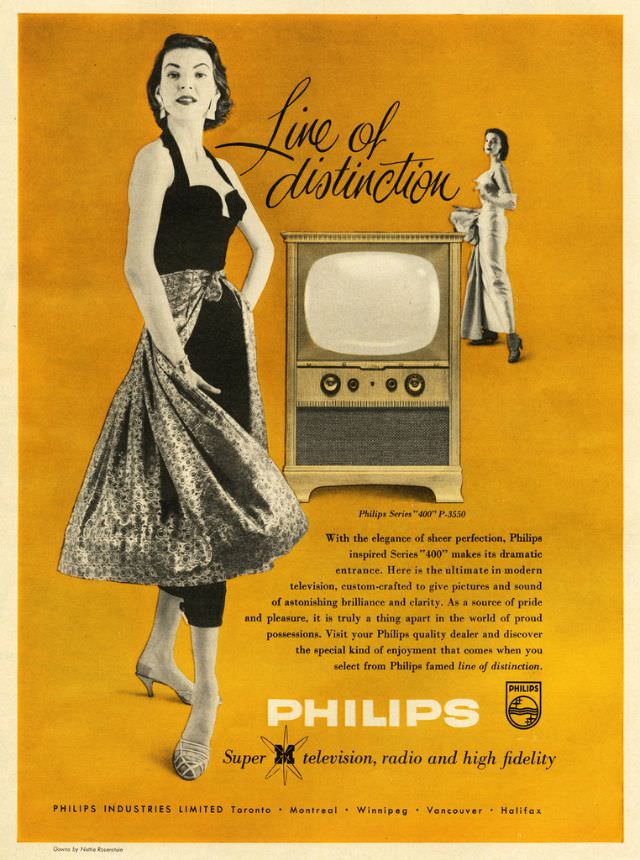

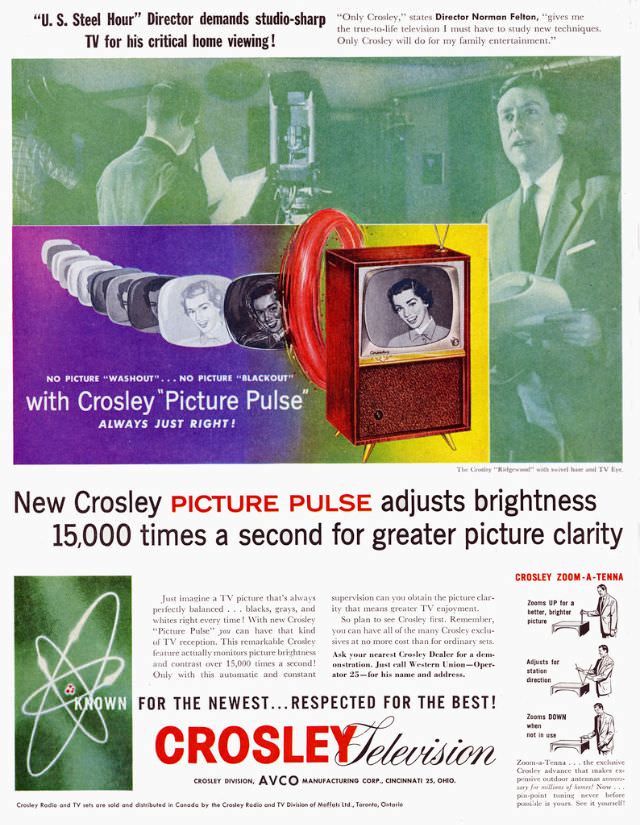

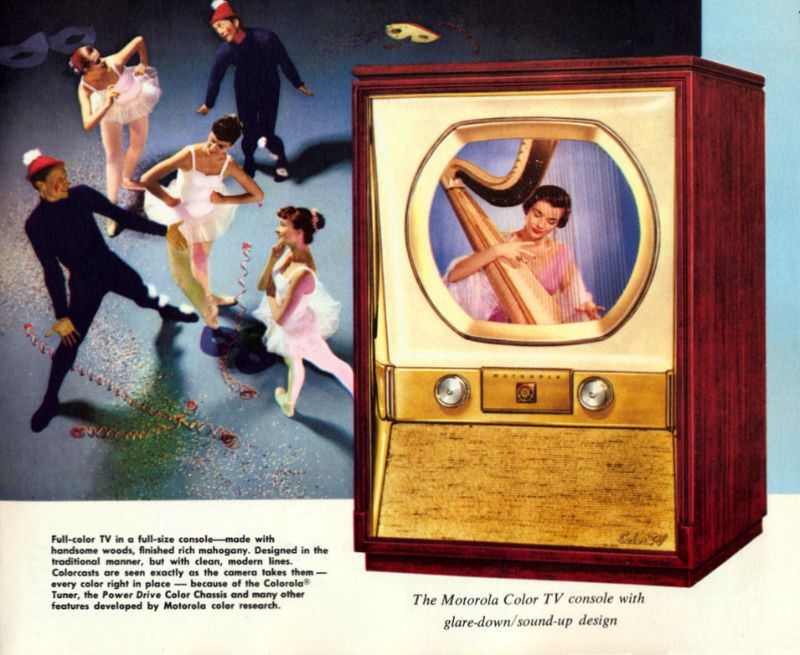

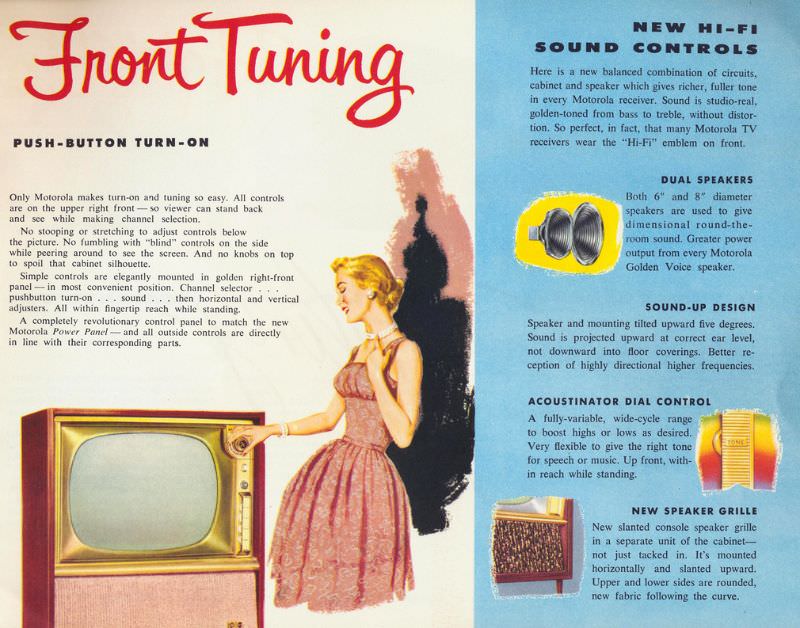

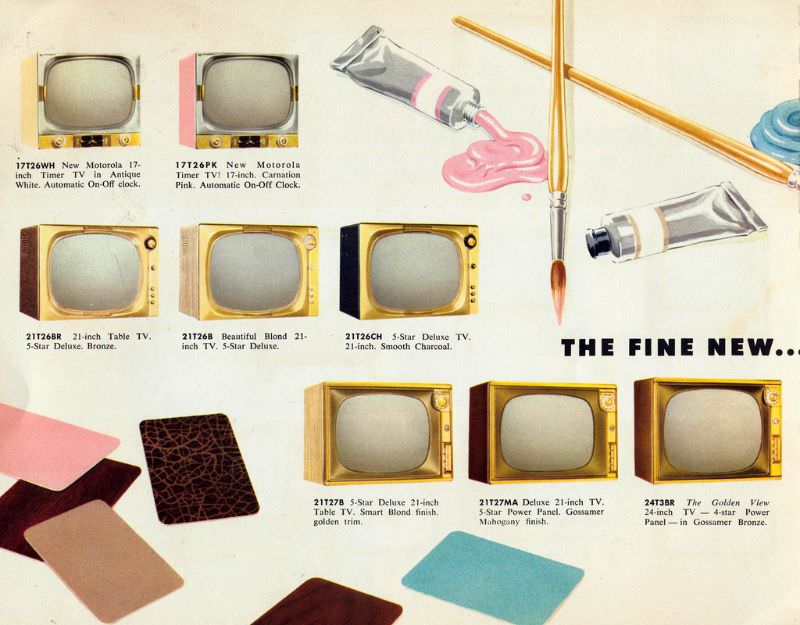

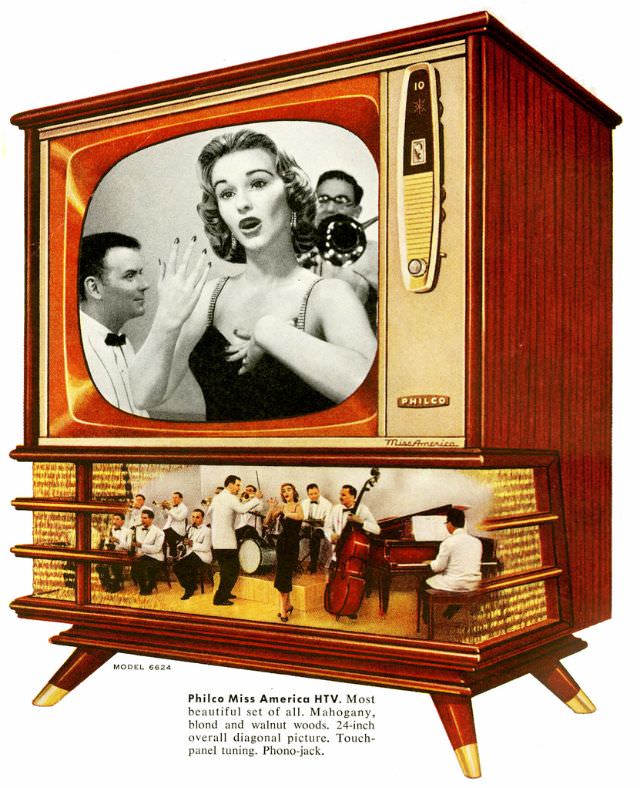

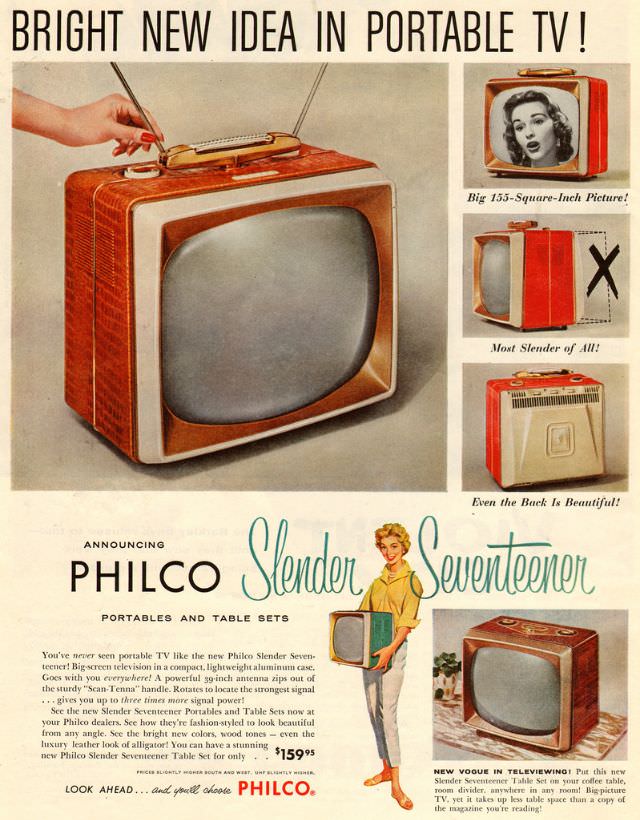

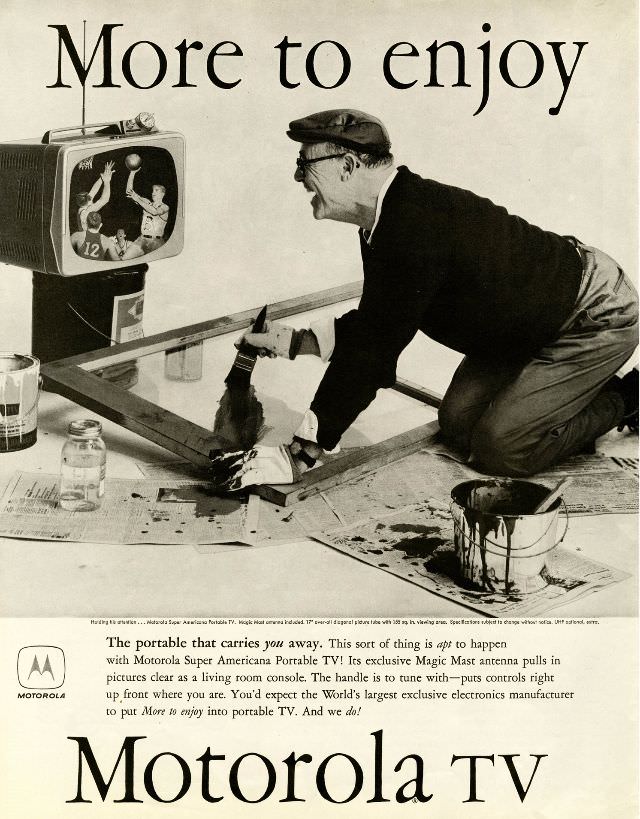

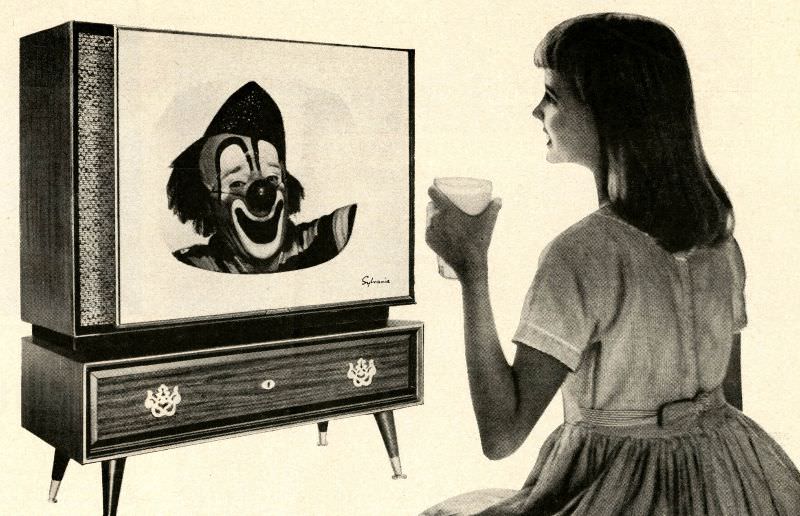

Manufacturers and advertising agencies created many engaging ads to entice buyers to buy TVs. Early electronic television sets used vacuum tubes as analog circuits and were large and bulky. One example is the RCA CT-100 color TV set, which used 36 vacuum tubes. In 1952, Sony founder Masaru Ibuka predicted that transistor-based electronics would lead to smaller and more portable televisions following the invention of the first working transistor at Bell Labs. In 1960, Sony released the TV8-301, the first transistorized portable solid-state television set. The British Radio Corporation released the first transistorized color TV set in 1967, the HMV Colourmaster Model 2700. TV viewing began to transform from a communal to a solitary activity.

Sony sold over 4 million portable television sets worldwide by 1960. American television viewers could watch, for example, ‘The Texaco Star Theater (1948)’, starring Milton Berle, and ‘Howdy Doody (1947)’, a children’s show. Early television programs such as ‘Amos ‘n’ Andy (1951)’ and ‘The Jack Benny Show (1950-65)’ borrowed many elements from the more established, older Big Brother of radio: network television. The formats of the new programs, including newscasts, situation comedies, variety shows, and dramas, were primarily borrowed from the radio. This new medium was funded by the profits earned by NBC and CBS in the radio industry. Television networks would soon be making substantial profits, and network radio would be all but forgotten, except for hourly newscasts. It wasn’t easy to develop ideas on how to use the visual element television added to the radio. In particular, news programs tended to fill the screen with “talking heads,” newscasters reading the news. The networks initially used newsreel companies, whose work had previously been shown in movie studios, to deliver news events.

The television industry was in a transitional phase by the mid-1950s. Most television programming broadcasts from New York City was based on the city’s theatrical traditions in the early decade. The network schedules soon included most of entertainment television’s iconic genres, such as situation comedies, westerns, soap operas, adventure shows, quiz shows, and police and medical dramas. During this time, the television production industry was moving from New York to Los Angeles, resulting in programming changes: the live theater was giving way to films in the Hollywood tradition. A notable example of the “spectacular” was Peter Pan (1955), starring Mary Martin, which attracted 60 million viewers. In 1954, ABC turned its first profit with youth-oriented shows like Disneyland (now broadcast under other names) and The Mickey Mouse Club. During the mid-1950s, both major networks drew heavily on another medium: theater. CBS and NBC presented drama anthologies such as Kraft Television Theater (1947), Studio One (1948), Playhouse 90 (1956), and The U.S. Steel Hour (1953). Some of the most memorable television dramas of the era were Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty (1955), starring Rod Steiger (Ernest Borgnine starred in the film), and Reginald Rose’s Twelve Angry Men (1954).