During Queen Victoria’s reign from 1837 to 1901, England emerged as the world’s foremost superpower. London, as the heart of this empire, pulsed with life and energy. The city was a bustling metropolis filled with magnificent palaces, grand buildings, and thriving businesses. However, beneath this glittering surface lay a stark and harsh reality. Poverty was rampant, creating a sharp contrast to the wealth surrounding it. Today, colorized photographs of Victorian London allow us to step back in time and see this complex world more vividly. These images provide a glimpse into everyday life during the late 19th century, revealing both its beauty and its struggles.

The Growth of London

In the 19th century, London underwent a rapid transformation. The population exploded, growing from just over 1 million in 1801 to approximately 5.6 million by 1891. This growth made London the largest city in the world and the capital of the British Empire. By 1897, the population of Greater London, which included areas beyond the City of London, was estimated to be around 6.3 million.

This population boom was driven by people flocking to the city for work and opportunity. London had become a magnet for those seeking a better life. By the 1860s, the population of London was significantly larger than that of other major cities, including Beijing, Paris, and New York City. This rapid urbanization brought many challenges, especially for the working class..

Read more

The Wealth and Poverty of Victorian London

While London was a city of wealth and luxury, it was also a place of deep inequality. The disparity between the rich and the poor was stark. In the affluent areas of the city, grand homes and elegant shops contrasted sharply with the squalid conditions found in the slums. George W. M. Reynolds, a writer from the time, described this contrast vividly. In 1844, he wrote, “The most unbounded wealth is the neighbor of the most hideous poverty.”

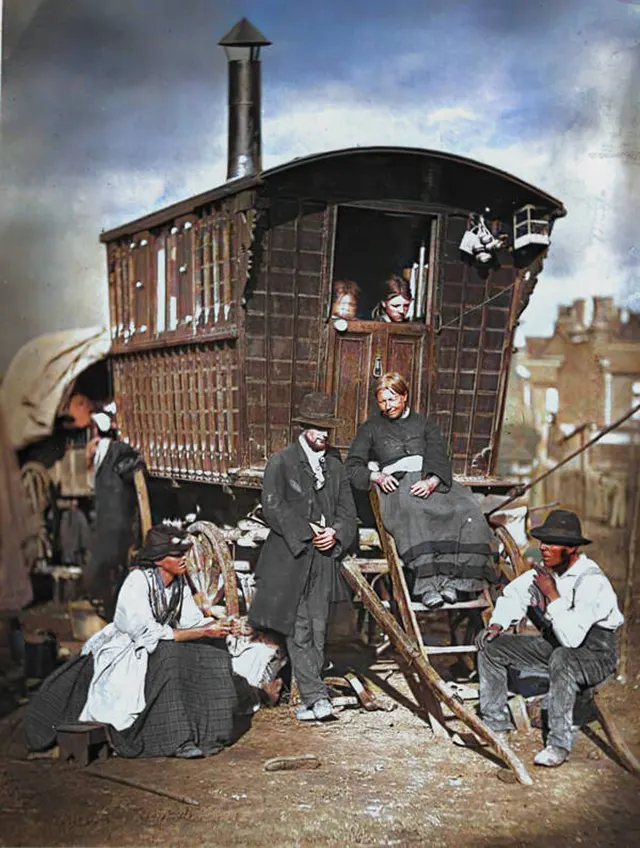

He went on to highlight the desperate conditions of the poor, who often resorted to pawn shops to survive. Many were forced to sell their clothes and possessions just to buy food. Public houses, or gin-palaces, served as places for the downtrodden to drown their sorrows, while workhouses became a refuge for the destitute. These institutions, while meant to provide aid, often became places of despair.

The East End: A Hub of Struggle

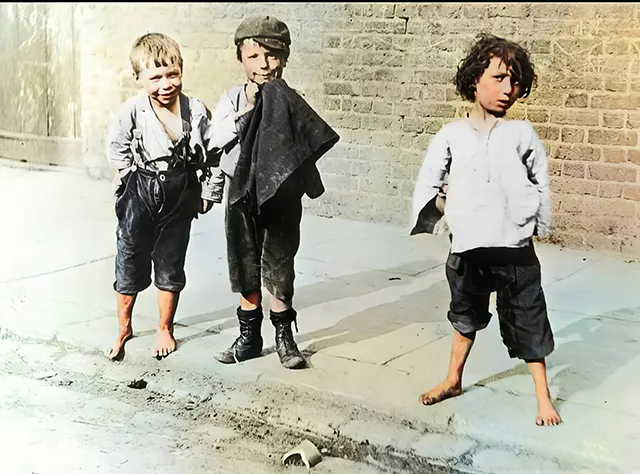

The East End of London was particularly known for its struggles. The area was home to many of the city’s working poor, who lived in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions. By the late 19th century, the East End earned a notorious reputation for crime, poverty, and overcrowding. The 1881 census recorded over 1 million inhabitants in the East End, and a third of them lived in poverty.

American author Jack London visited the East End in 1903 and described his shock at the poverty he witnessed. Many Londoners had never ventured into the East End, despite living in the same city. When he approached a travel agency to get information about the area, he was told to consult the police instead. This reluctance to engage with the East End reflected a wider societal neglect of its poorest residents.

In his account, London described the East End as an “unending slum.” The streets were filled with people who appeared worn down by life. He noted the sight of drunken men and women and the sounds of arguments in the air. This vivid description highlights the grim reality many faced in this part of London.

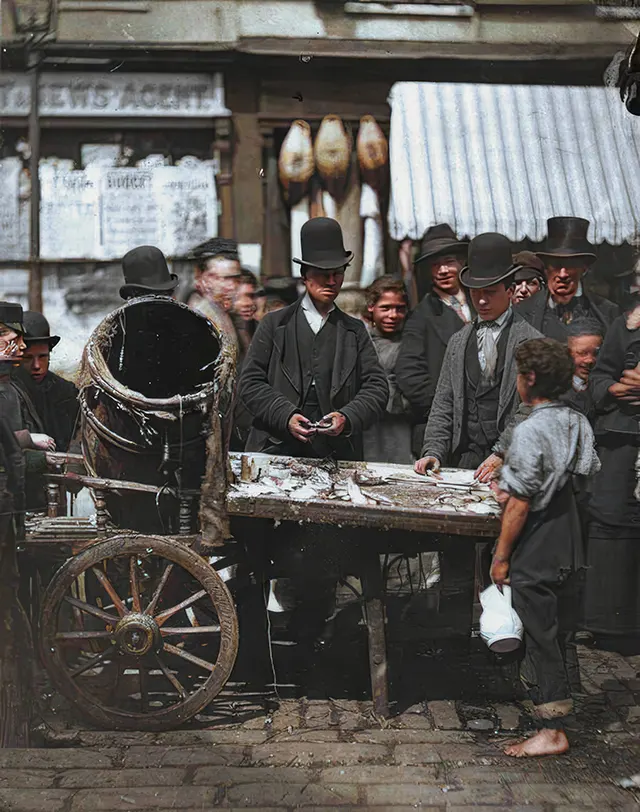

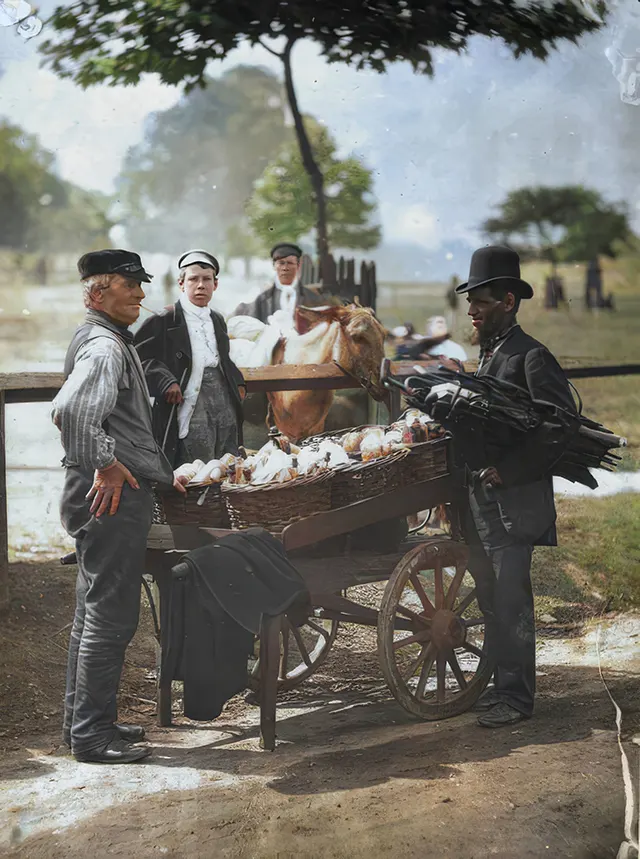

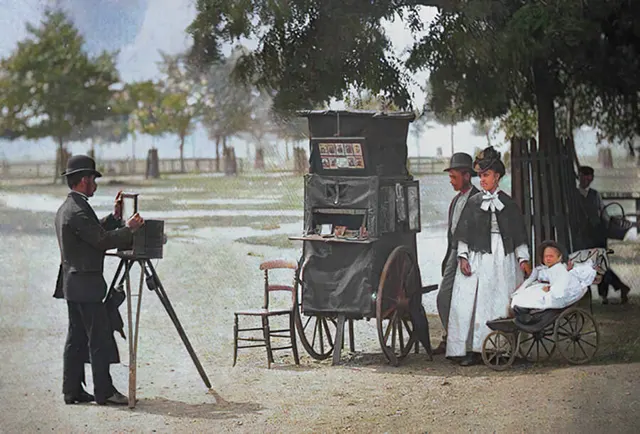

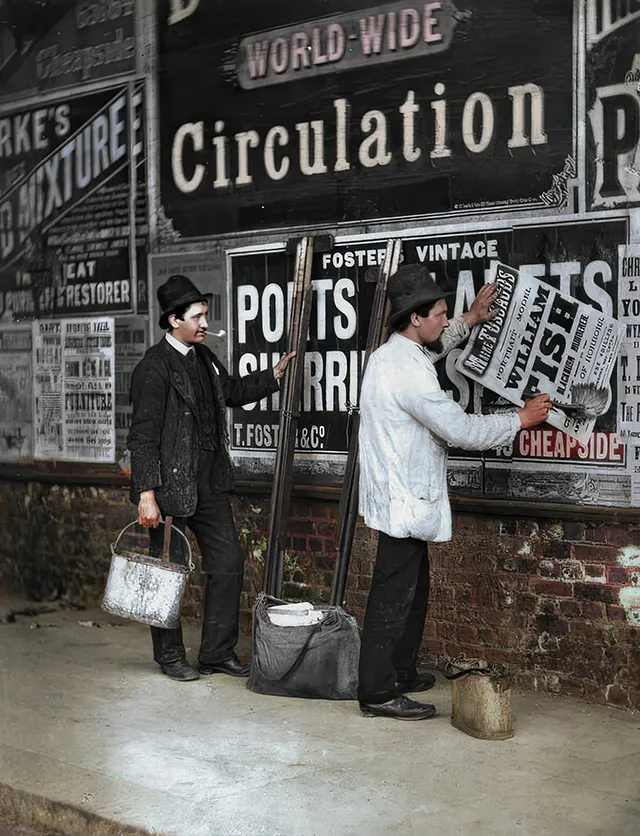

The following Colorized photographs of Victorian London provide a new perspective on this historic era. These images allow us to move beyond the typical black-and-white photographs that often dominate our understanding of the past. By adding color, these photographs bring life and vibrancy to scenes that once seemed distant and monochrome.

Colorization helps to humanize the people in these photos. It reveals the clothing styles, the conditions of the streets, and the everyday life of Londoners. The colorized images feature everything from the bustling markets to the quiet moments in the parks. They show us the faces of working-class individuals and families, allowing us to connect with them on a personal level.