On June 6, 1889, the Great Seattle Fire destroyed Seattle’s central business district. Burning through the afternoon and night, it was less than a day-long and occurred during the same summer as the Great Spokane Fire and the Great Ellensburg Fire. Seattle rebuilt quickly using brick buildings that stood 20 feet above the original street level. During reconstruction, its population surged, making it the largest city in the newly admitted state of Washington.

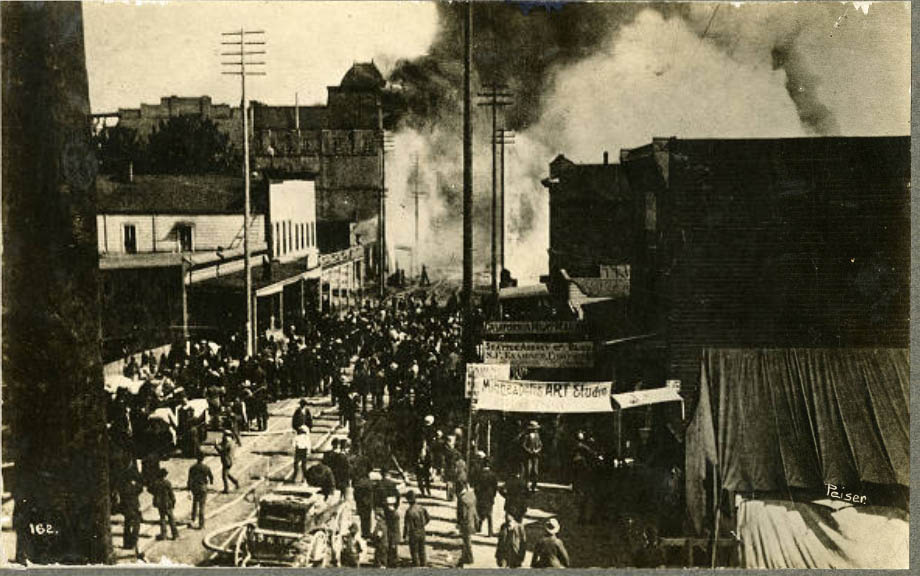

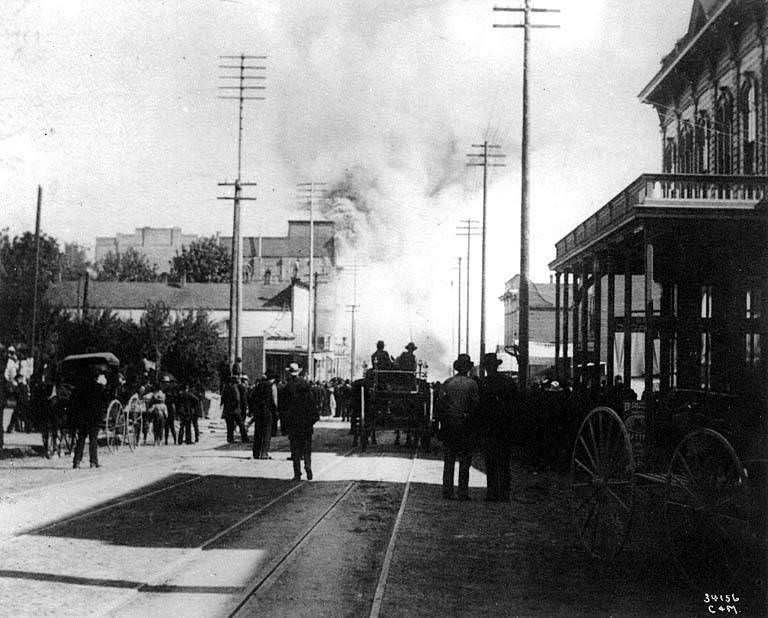

Seattle had experienced a beautiful spring in 1889. There was little rain, and temperatures were consistently in the 70s. The perfect weather proved to be a disaster, as the dry conditions conspired with a handful of other factors to cause the worst Fire in the city’s history. An assistant to Victor Clairmont, John Back, was heating glue over a gasoline fire in his woodworking shop at Front Street (now First Avenue) and Madison Avenue in the afternoon of June 6, 1889. Around 2:15, the glue boiled over, caught fire and spread to the floors covered by wood chips and turpentine. The water he used to douse the Fire served only to thin it and spread the flames further. By 2:45, the fire department had arrived on the scene, and everyone had been evacuated safely. The Fire had already spread out of control due to the dense smoke. The Fire rapidly spread to the Dietz & Mayer Liquor Store, which exploded, the Crystal Palace Saloon, and the Opera House Saloon. The entire block from Madison to Marion was on Fire due to alcohol.

Inadequate water supply

Fighting the Fire proved challenging due to Seattle’s water supply. Spring Hill Water Company was then in charge of providing water. There were only a few hydrants on each street, and the ‘pipes,’ which were hollowed-out logs (some of which would burn in a fire), were small. The water pressure dropped to the point that the hoses stopped working as more hoses were added to fight the Fire. Firefighters attempted to contain the Fire by pumping water onto the Commercial Mill from Elliott Bay, but the tide was out, and the hoses were not long enough to reach the side closest to the Fire. As the water pressure dropped, crowds harassed the firefighters. In addition to the diminishing water supply, the wind was a factor in spreading the Fire. Within a short time, the mill, Colman Building, and Opera House caught fire. During the Fire, Mayor Moran took command of the city from acting as Fire Chief Murphy (ironically, Chief Collins was away at a fire-fighting convention in San Francisco). Moran blew up the Colman block to put the Fire, but it spread past the block and up the wharf and Second Avenue.

The Fire quickly spread from Third Avenue to Trinity Church and then moved to the three-story Courthouse across the street. Eventually, the Fire spread to Fourth and University, but many buildings, including the Courthouse, were saved. A fire department attempt to water the Courthouse was unsuccessful because of the low pressure, which meant the hoses could only reach the first floor. Lawrence Booth, a quick-thinker, climbed to the Courthouse’s roof and poured buckets of water down its sides, saving both the building and public records. Jacob Levy’s house and the Boston Block were saved because of Booth’s leadership. The house of Henry Yesler was also saved, thanks to a person who covered the structure with wet blankets.

Destruction and loss caused by the Fire

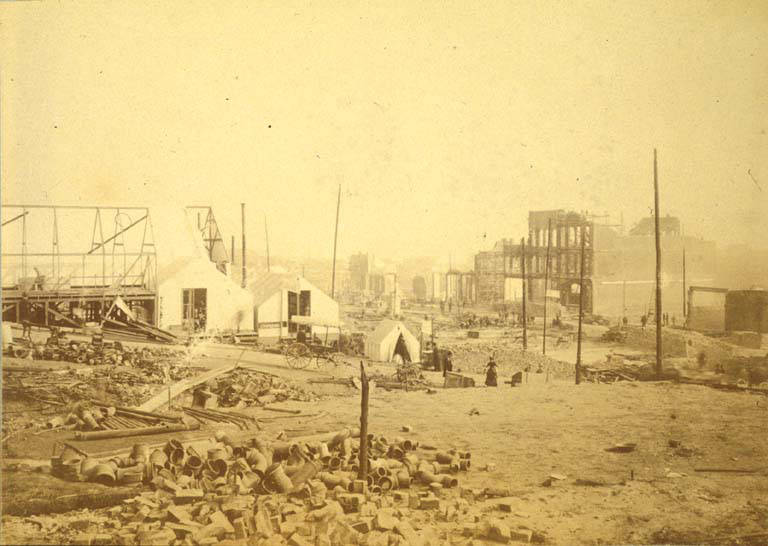

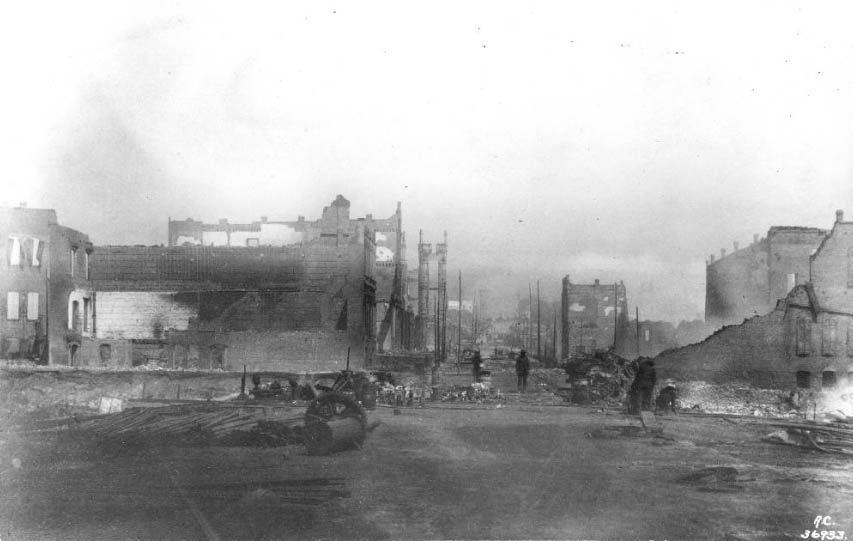

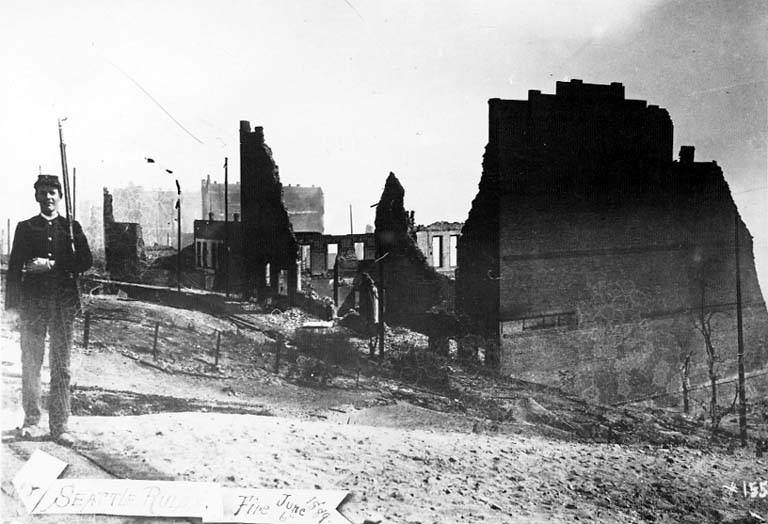

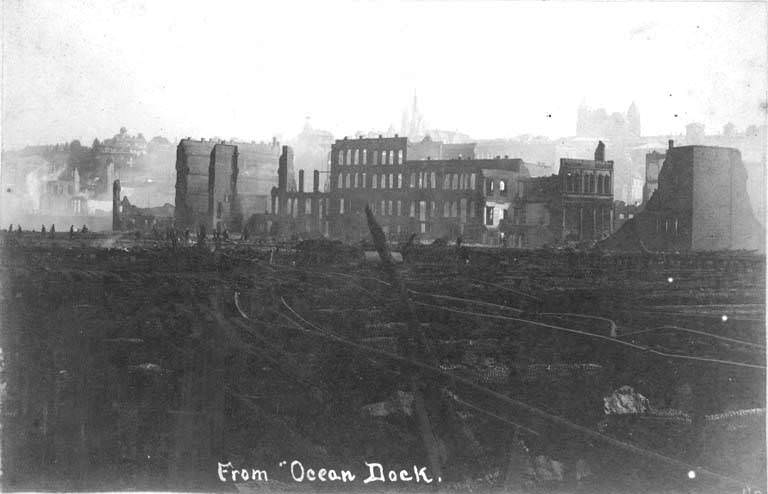

The Fire had burned 25 city blocks by the morning of June 7, including the downtown business district, four piers, and several railroad terminals. Although there was extensive property destruction, few or no people were killed. James Goin, a young boy, has been killed in the blaze, but no reliable records have been found. During the cleanup process, over 1 million rodents were killed. Tens of thousands of people were displaced, and 5,000 men lost their jobs. More than $8 million worth of losses were estimated for the city, and that does not include people’s losses or damage to water and electrical systems. Total losses could be as high as $20 million.

The aftermath of the Fire

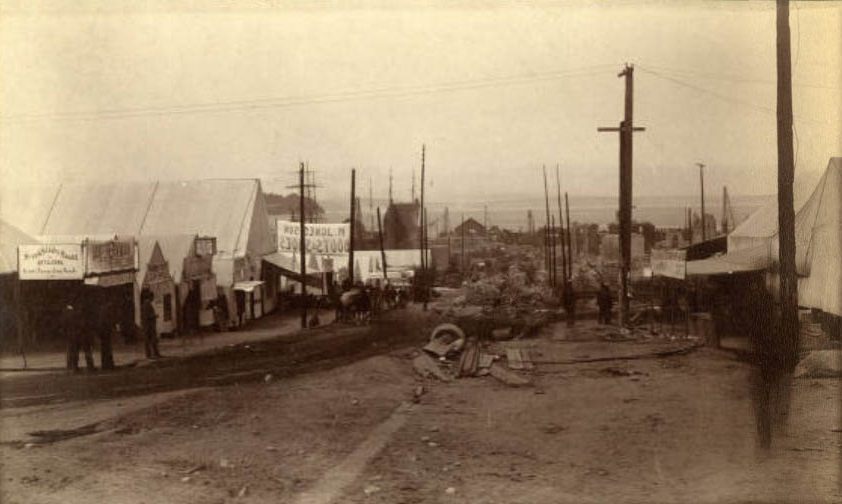

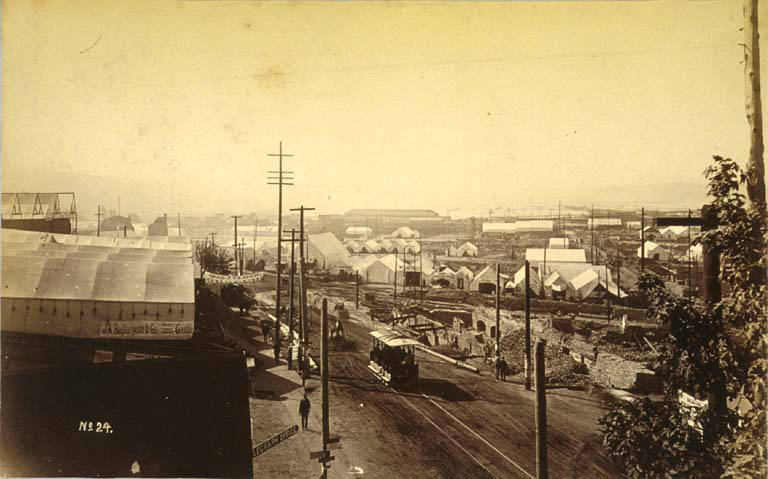

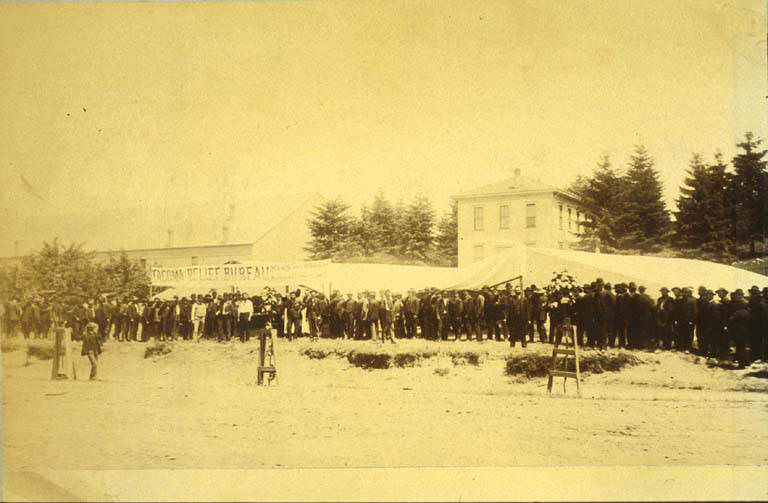

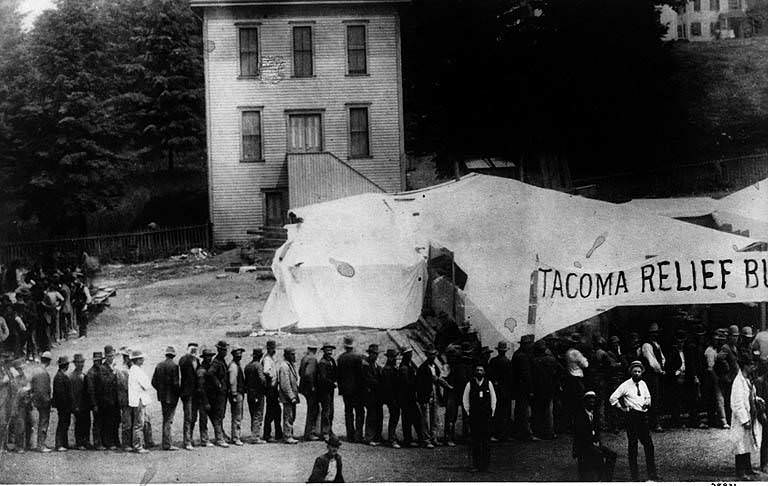

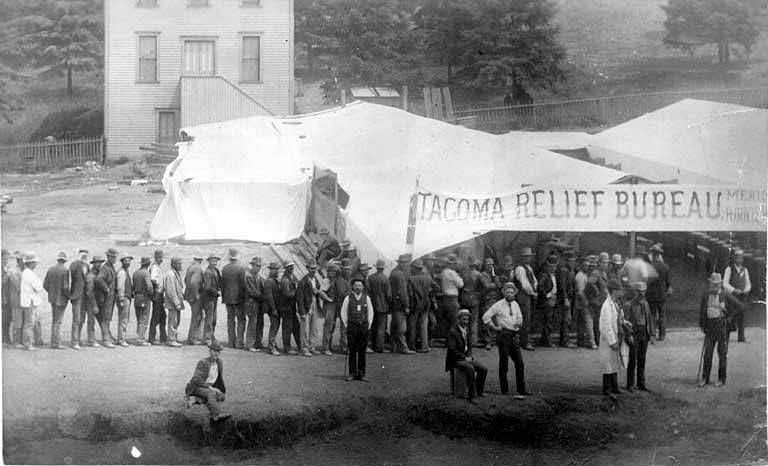

The city didn’t take much time to mourn. On June 7, 600 businessmen met in Seattle at 11 am to discuss coping with the current situation and plan for the future. During the two weeks of martial law, two hundred special deputies were sworn in to combat looting. In response to the charitable donations from all over the country, a relief committee was formed. Tacoma, a former rival but now an ally, collected $20,000 and sent a relief committee to help. A dining hall was converted from the armory so that displaced citizens could eat. The supplies from San Francisco (many of which had been ordered before the Fire) arrived by June 18. Relief bureaus closed as quickly as June 20 since tent restaurants had been set up quickly and had been able to meet people’s needs. Within a month of the Fire, more than 100 businesses were operating from tents.

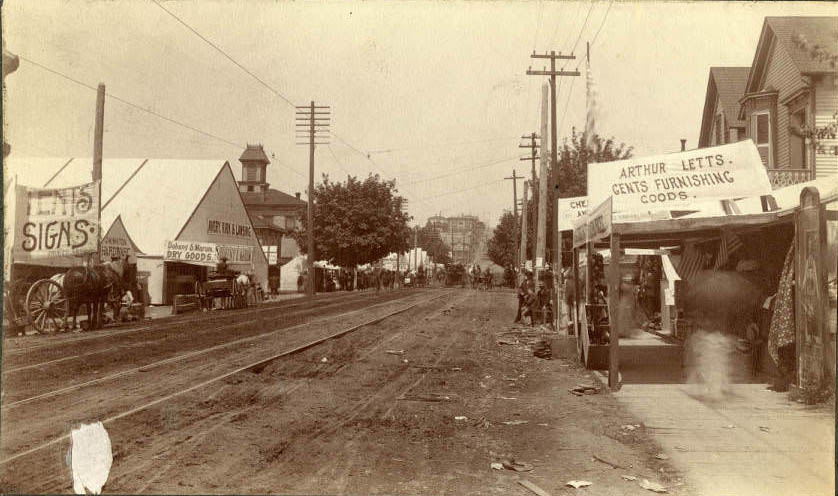

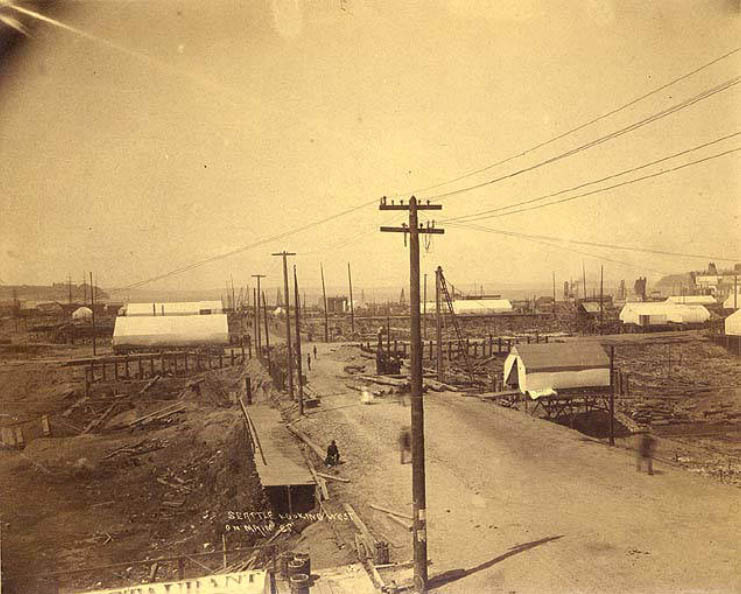

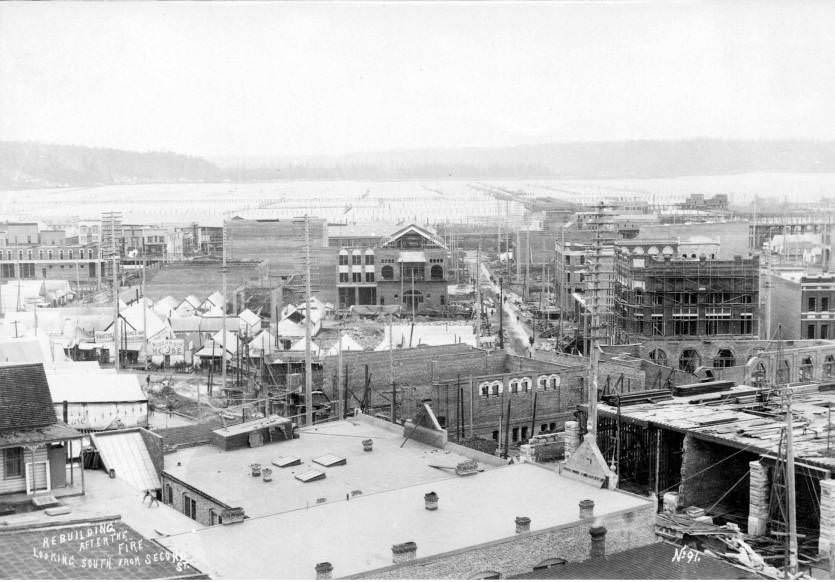

Most businesses opted to rebuild where they had been instead of relocating, and the rebuilding process began almost immediately. In the burned-out district, wood buildings were banned and replaced with brick buildings. The city’s hilly terrain was also leveled by raising streets to 22 feet in some places. In just one year, 465 buildings had been built, most of the reconstruction had been completed, and businesses had reopened.

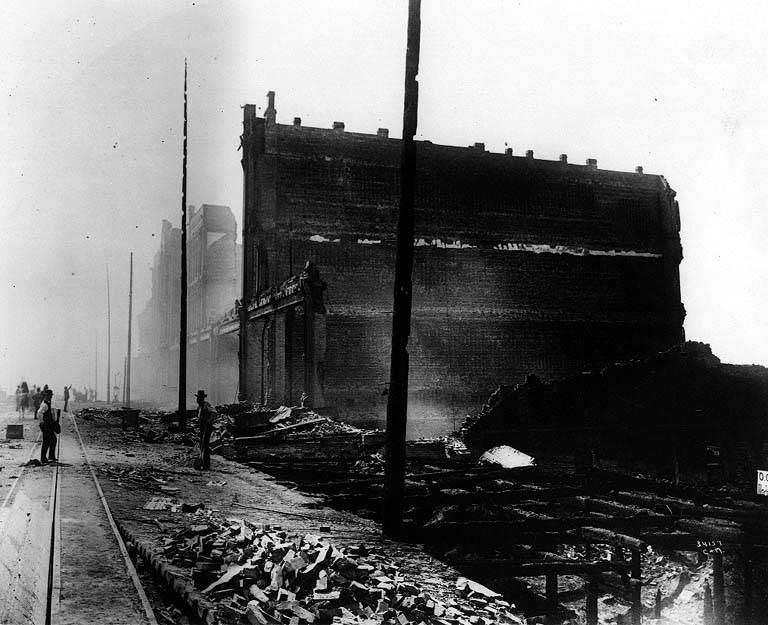

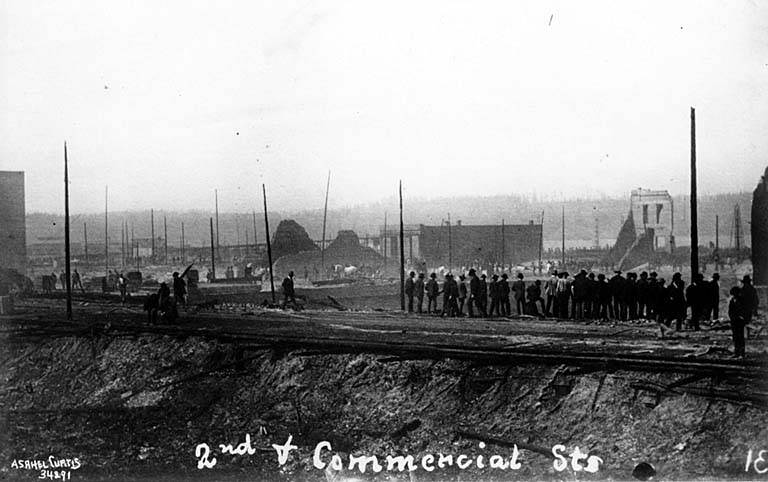

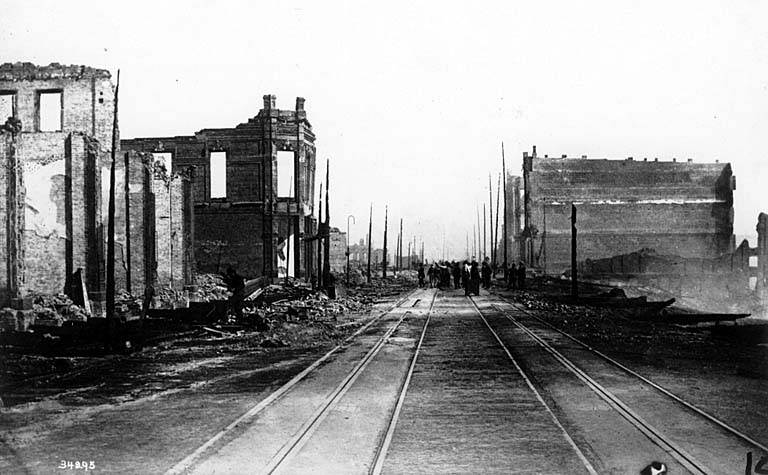

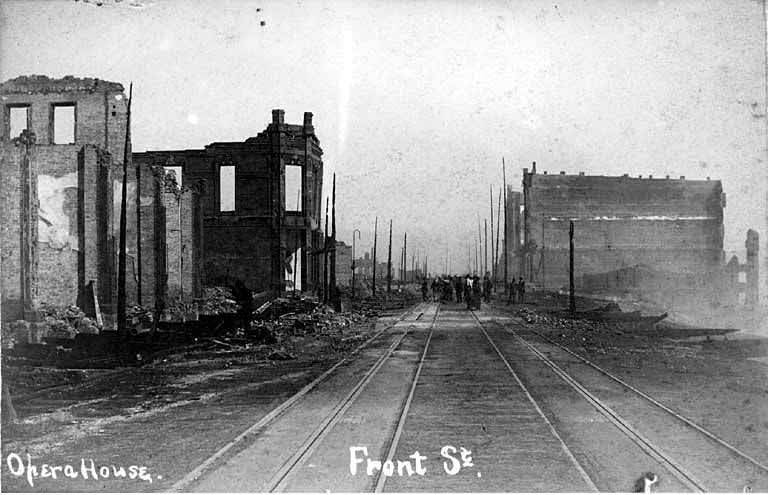

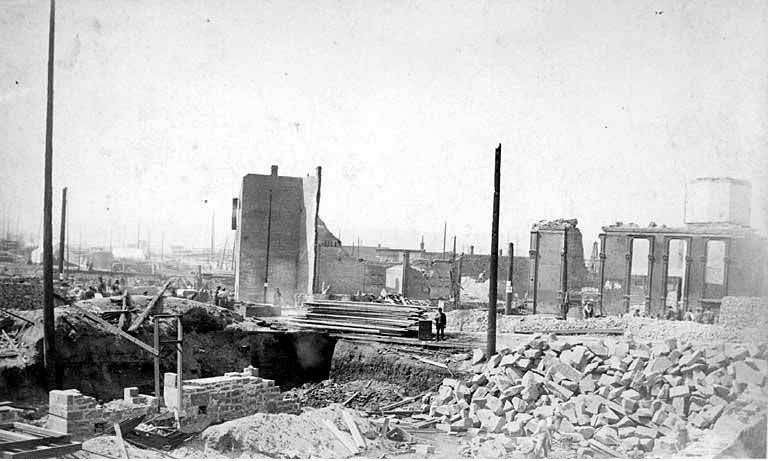

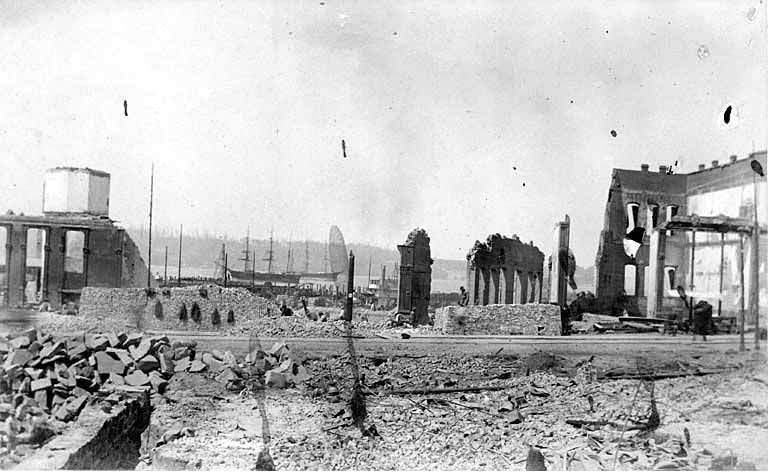

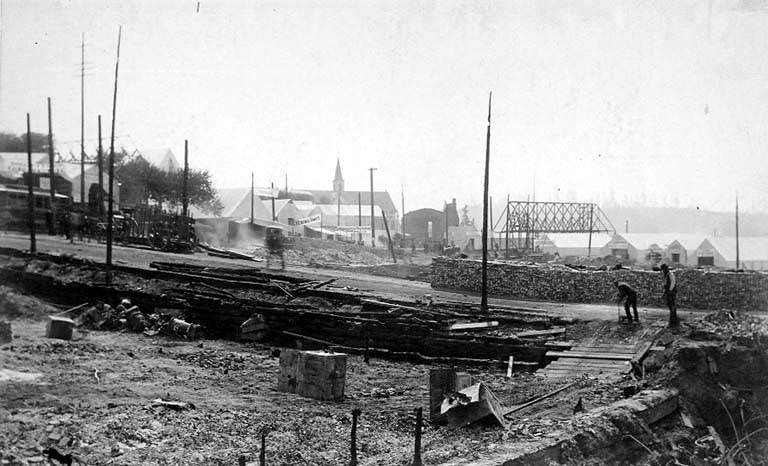

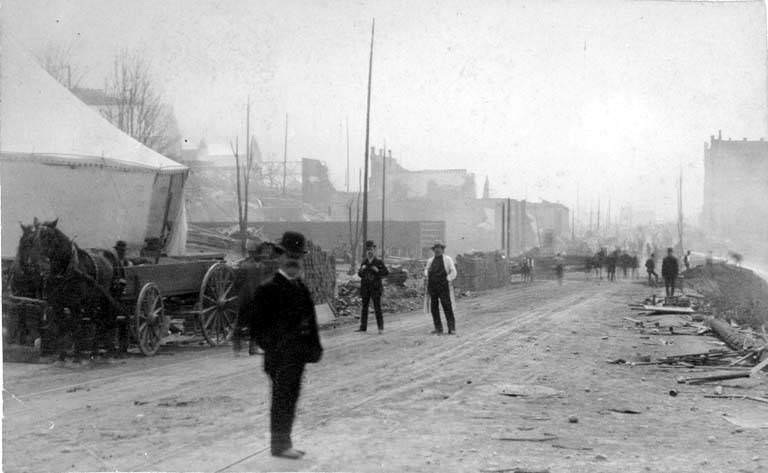

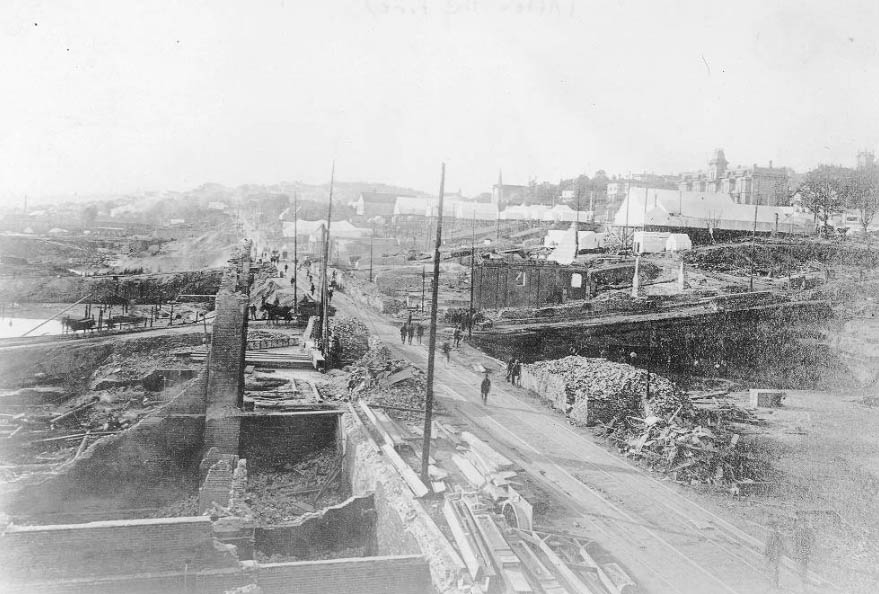

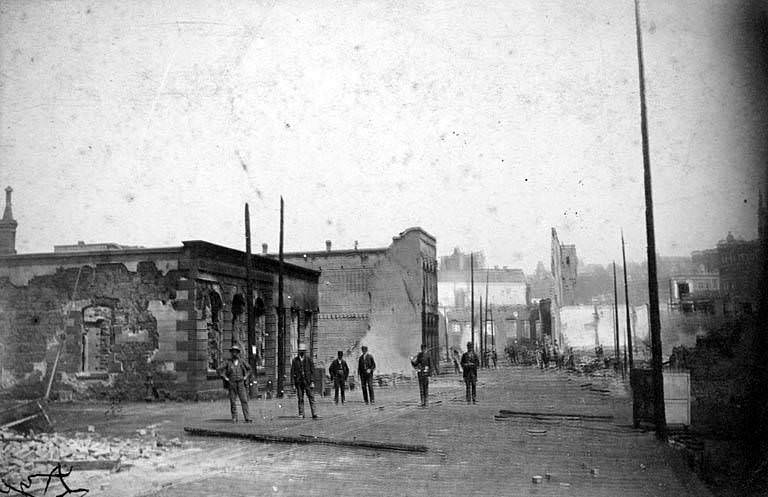

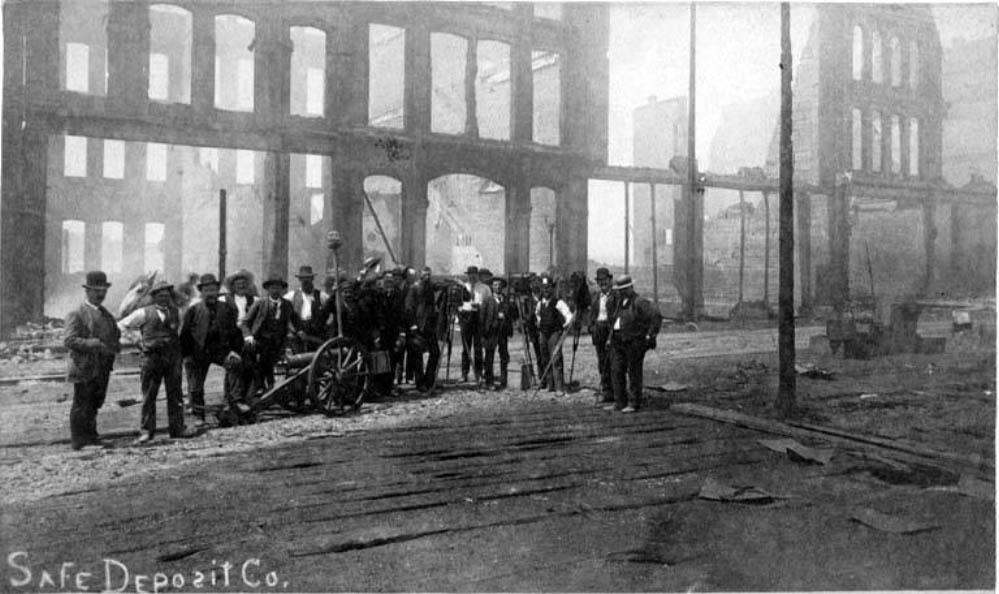

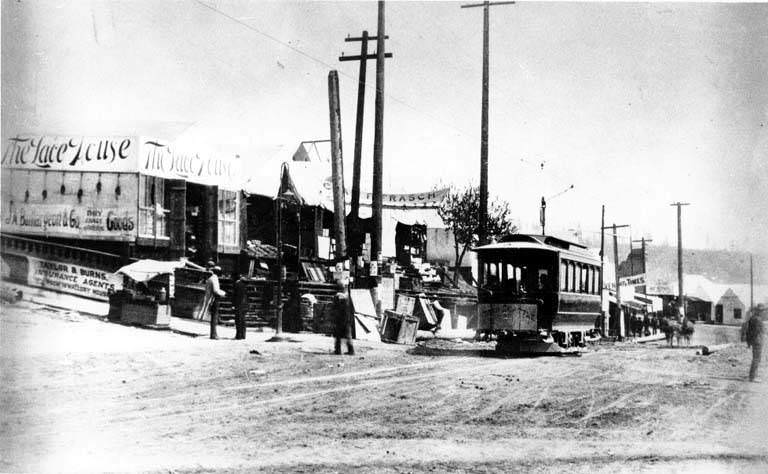

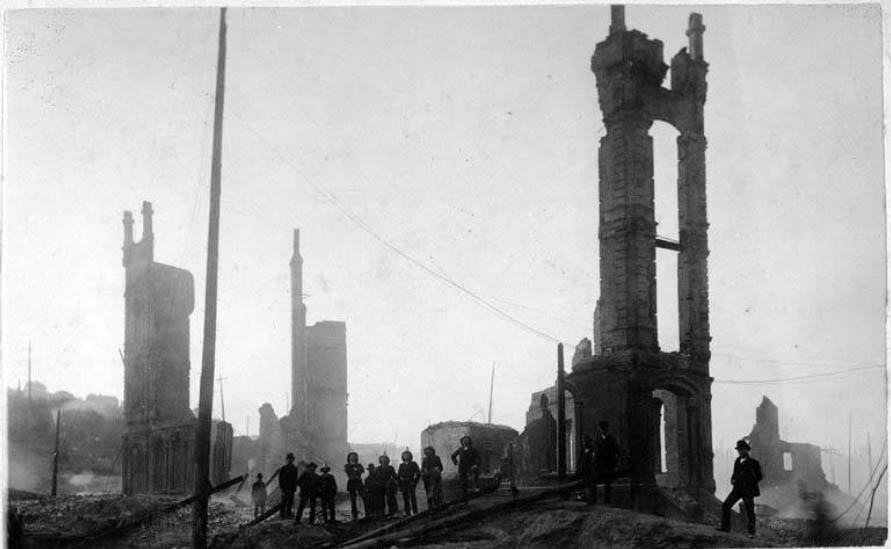

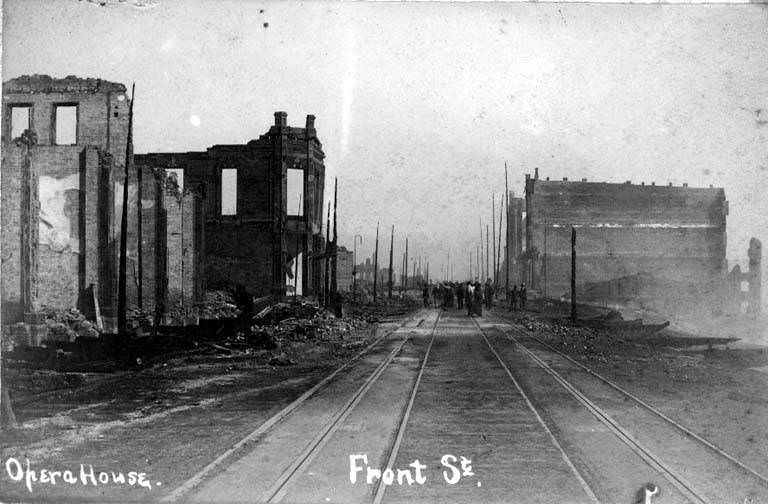

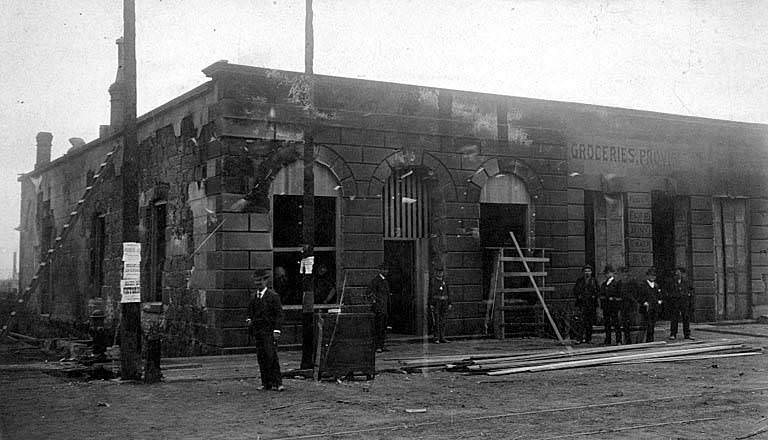

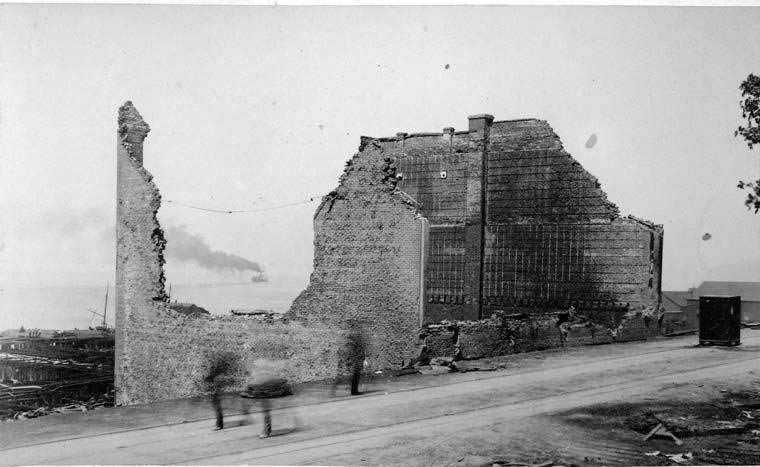

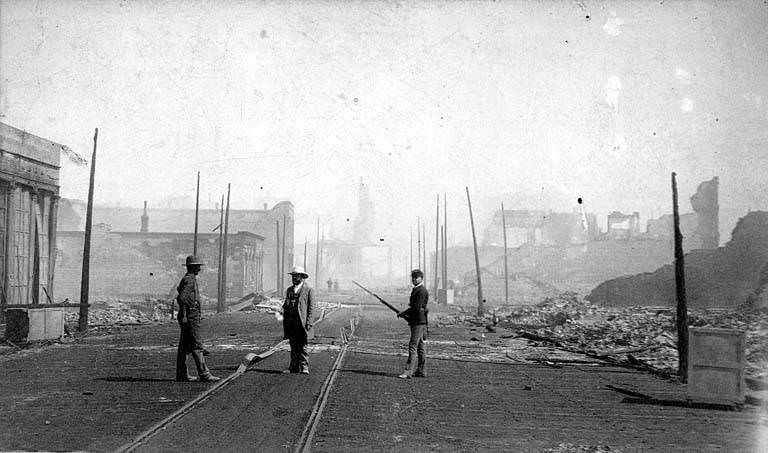

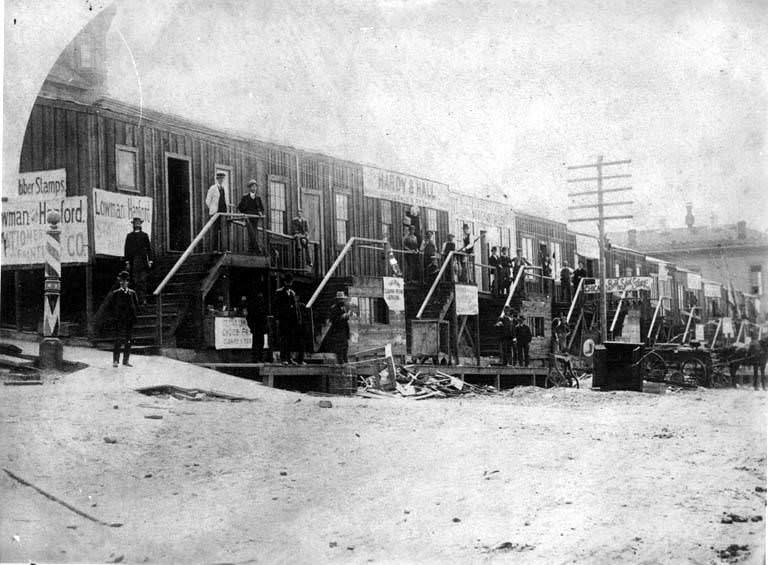

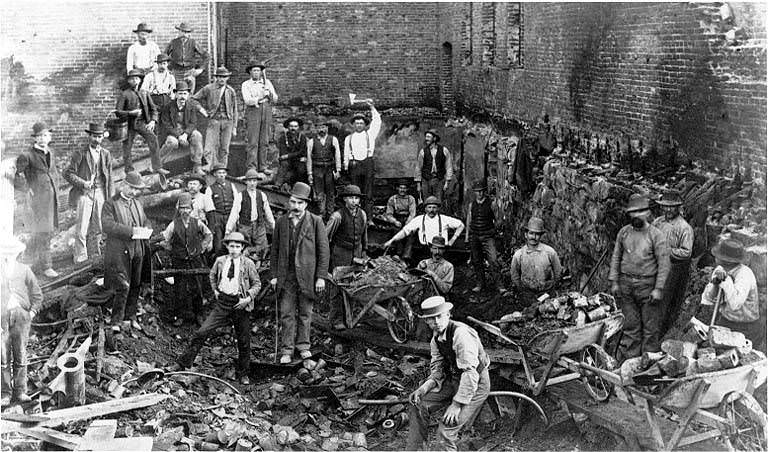

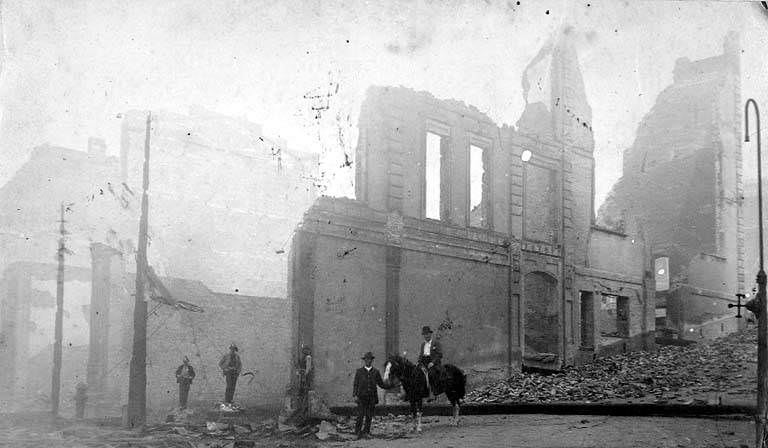

Below are some historical photos that depict the destruction and the aftermaths of the Great Seattle fire.

#1 Ruins of the Puget Sound National Bank, June 1889

#2 Ruins of the Occidental Hotel, June 1889

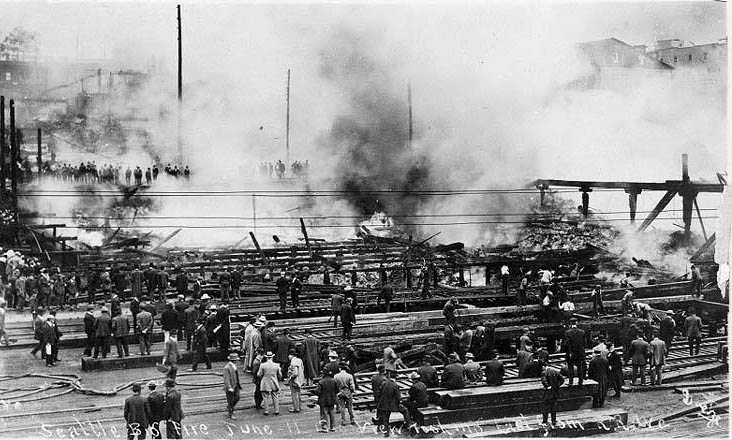

#3 Ruins of Main St. wharves following fire, ca. June 1889

#4 Ruins at 2nd Ave. and Columbia St. following the Great Fire, June 1889

#5 Reconstruction near 3rd Ave. and Yesler Way., June 1889

#6 Reconstruction near 2nd Ave. and Yesler Way, June 1889

#7 Reconstruction near 2nd Ave. and Madison St., June 1889

#8 Reconstruction near 2nd Ave. and James St., June 1889

#9 Reconstruction at 2nd Ave. and Spring St. following fire, June 1889

#10 Native American camp on Ballast Island, 1889

#11 Occidental Hotel ruins following fire, June 1889

#12 Frye’s Opera House Ruins, June 1889

#13 Fire ruins south from 1st Ave. S. and S. Washington St., 1889

#14 Fire ruins on west side of 1st Ave. between Columbia St. and Cherry St., June 1889

#15 Fire ruins on 1st Ave., north of Occidental Square, June 1889

#16 Fire ruins on 1st Ave., north of Occidental Square, June 1889

#17 Fire ruins of the Peoples Savings Bank near 1st Ave. and James St., June 1889

#18 Fire ruins near Post Ave. and Yesler Way, June 1889

#19 Fire ruins near Columbia St. and Cherry St., June 1889

#20 Fire ruins near 2nd Ave. and Columbia St., June 1889

#21 Fire ruins near 2nd Ave. and Cherry St., July 1889

#22 Fire ruins near 1st Ave. S. and S. Washington St., June 1889

#23 Fire ruins near 1st Ave. and Yesler Way, June 1889

#24 Fire ruins near 1st Ave. and Madison St., June 1889

#25 Fire ruins from 1st Ave. S. and S. Jackson St., June 1889

Looking Northeast from Jackson Street. Dexter Horton and Co. building left of center. Fire began at southwest corner of Front Street and Madison Street. 1. Yesler College. 2. Brown's skating rink. University of Washington Digital Collection regarding Yesler College: 'Boarding and day school for boys. Non-sectarian. Classical, scientific and commercial courses. Primary intermediate and preparatory departments.

#26 Fire origin from 1st Ave. and Spring St., June 6, 1889

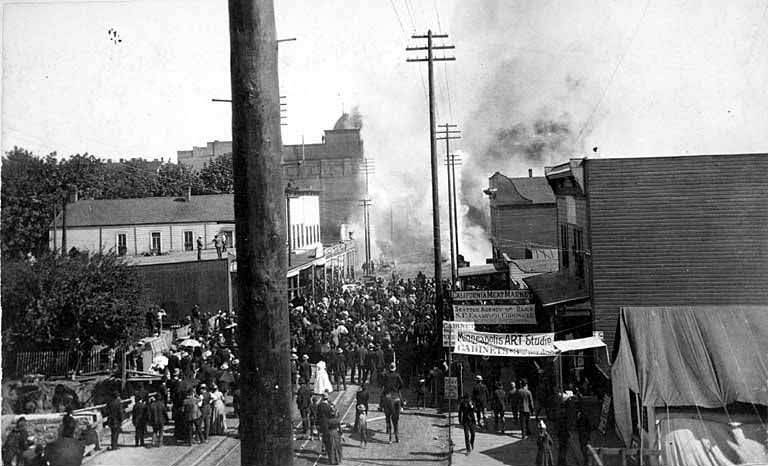

#27 Fire at southwest corner of 1st Ave. and Madison St., June 5, 1889

#28 Fire at 1st Ave. and Madison St., June 6, 1889

#29 Columbia and Puget Sound Railroad Depot and Machine Shop, 1880

#30 3rd Ave. and Jefferson St. after the fire, July 1889

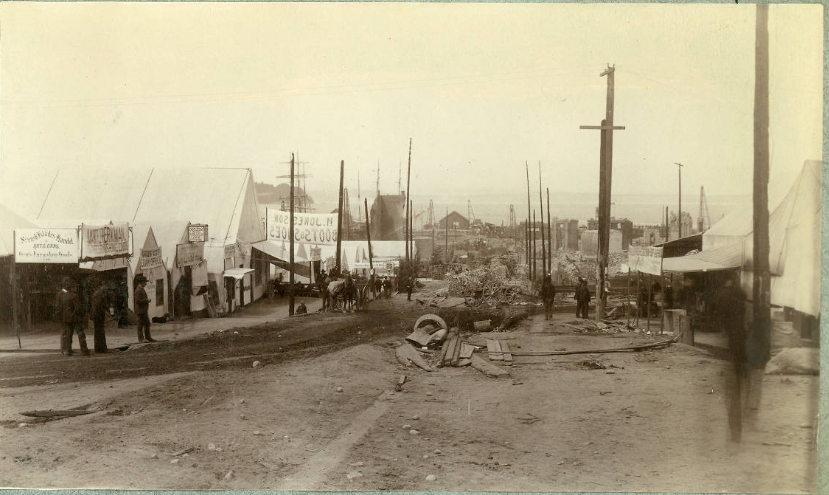

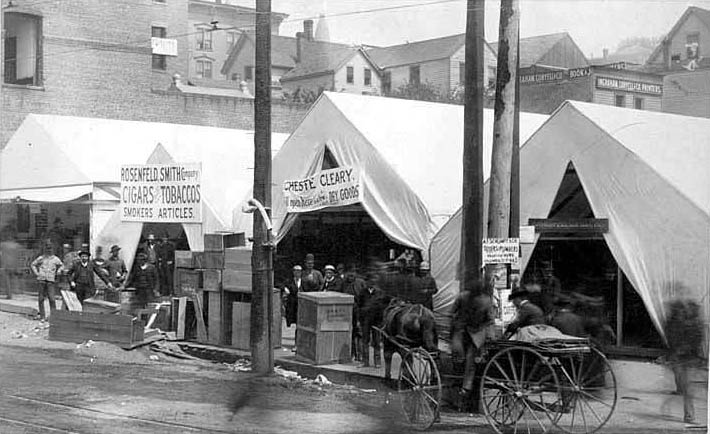

#31 Temporary buildings at 2nd Ave. and James St. following fire, June 1889

#32 Temporary tents at 2nd Ave. and Marion St. following fire, June 1889

#33 Yesler Way ruins after fire, June 6, 1889

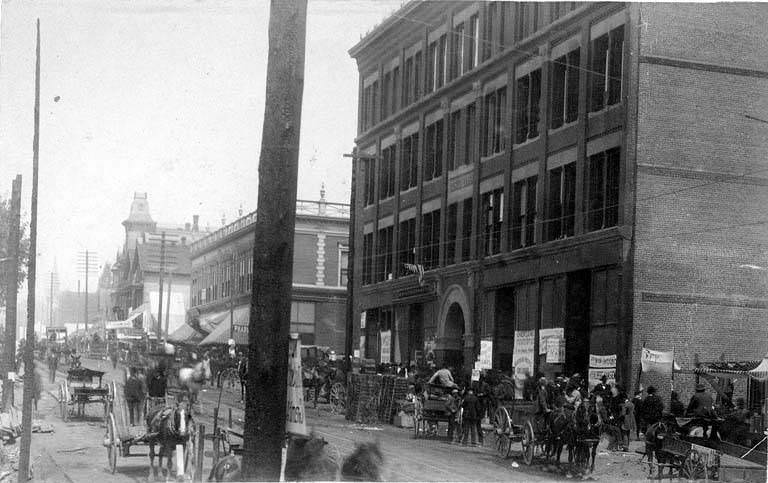

#34 1st Ave. from Columbia St. after Seattle fire of June 6, 1889.

#35 1st Ave., at the start of the fire, June 6, 1889

#36 1st Ave., from James St. after the fire of June 6, 1889

#37 1st Ave., looking north from Pioneer Square, 1890

#38 2nd Ave. from Cherry St. after the Seattle fire of June 1889

#39 2nd Ave. in Seattle after the fire of June 6, 1889

#40 Aftermath of a fire in Dawson, Yukon Territory, October 14, 1898.

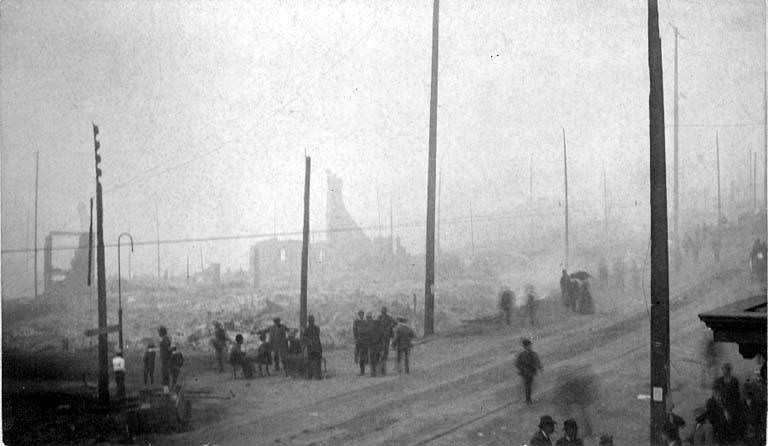

#41 Aftermath of Seattle fire of June 6, 1889 as seen from Railroad Ave. to the east.

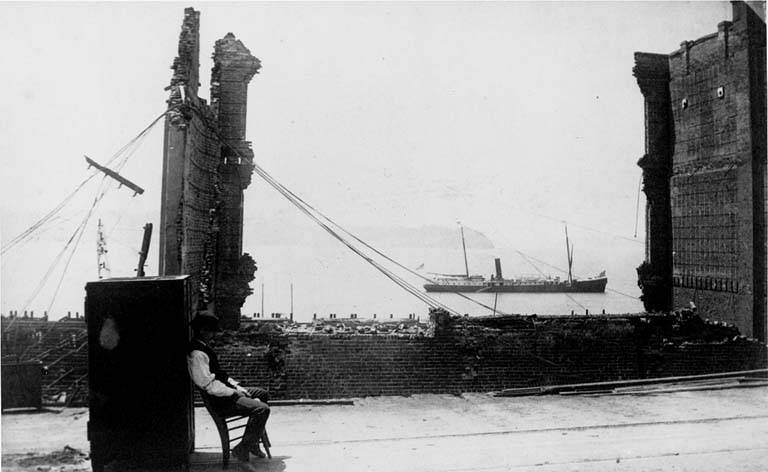

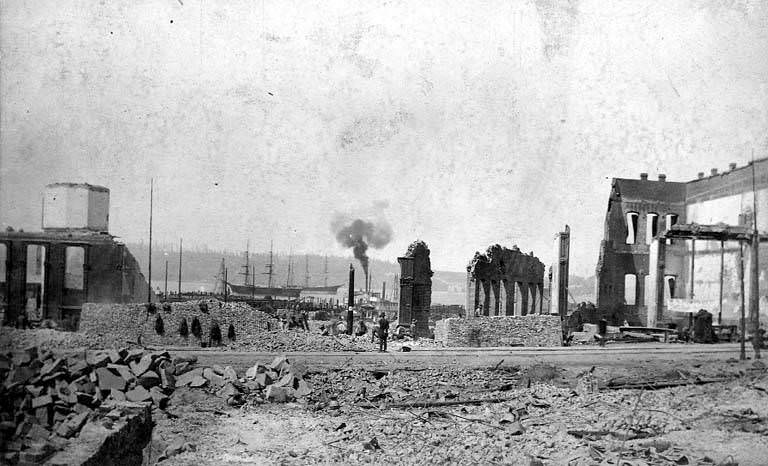

#42 Aftermath of Seattle fire of June 6, 1889, 2nd Ave. and Columbia St., showing destroyed wharves.

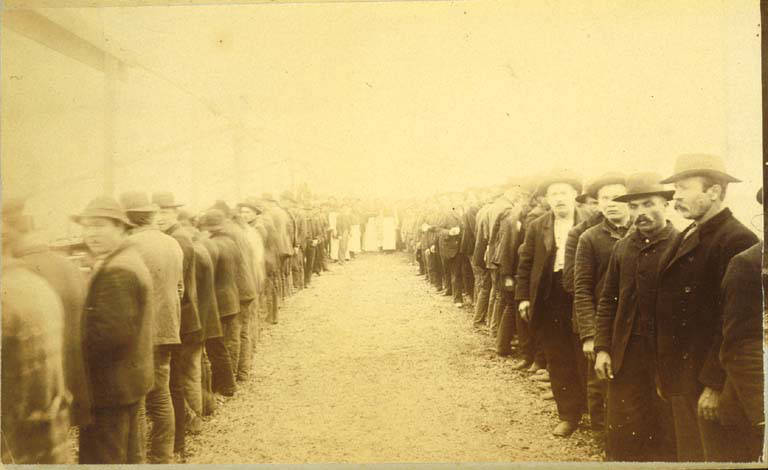

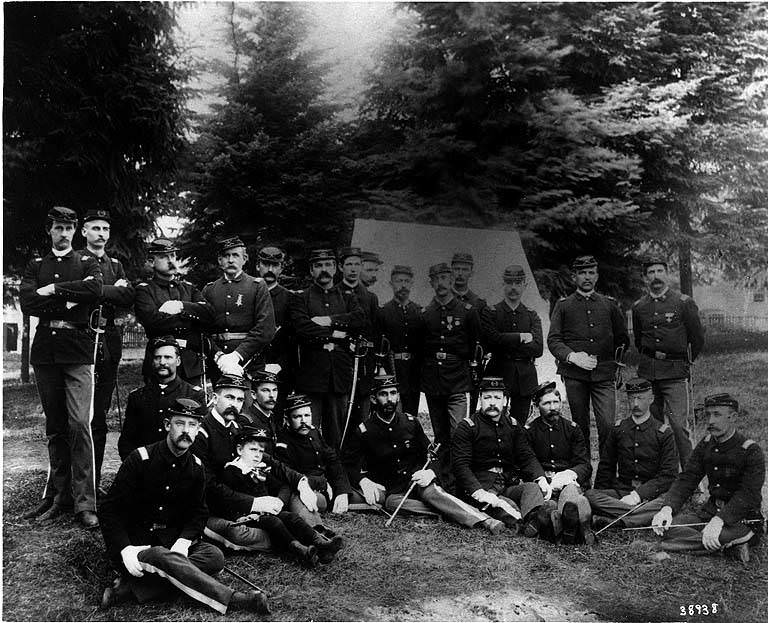

#43 Aftermath of Seattle fire of June 6, 1889, depicting officers of the Washington National Guard.1889

Standing, left to right: A. P. Brown, J. M. Howell, J. A. Hatfield, S. W. Scott, Wm. Kimball, J. C. Haines, Fred Grant, L. S. Booth, Paul D. Heirry, Wm. T. Sharpe; last four unidentified. Sitting, left to right: Wm. J. Gorham, E. M. Carr, Joseph Green, Joseph W. Phillips, Wm. R. Thornell, Wm. H. Fife, L. A. Dawson, C. L. F. Kellogg.