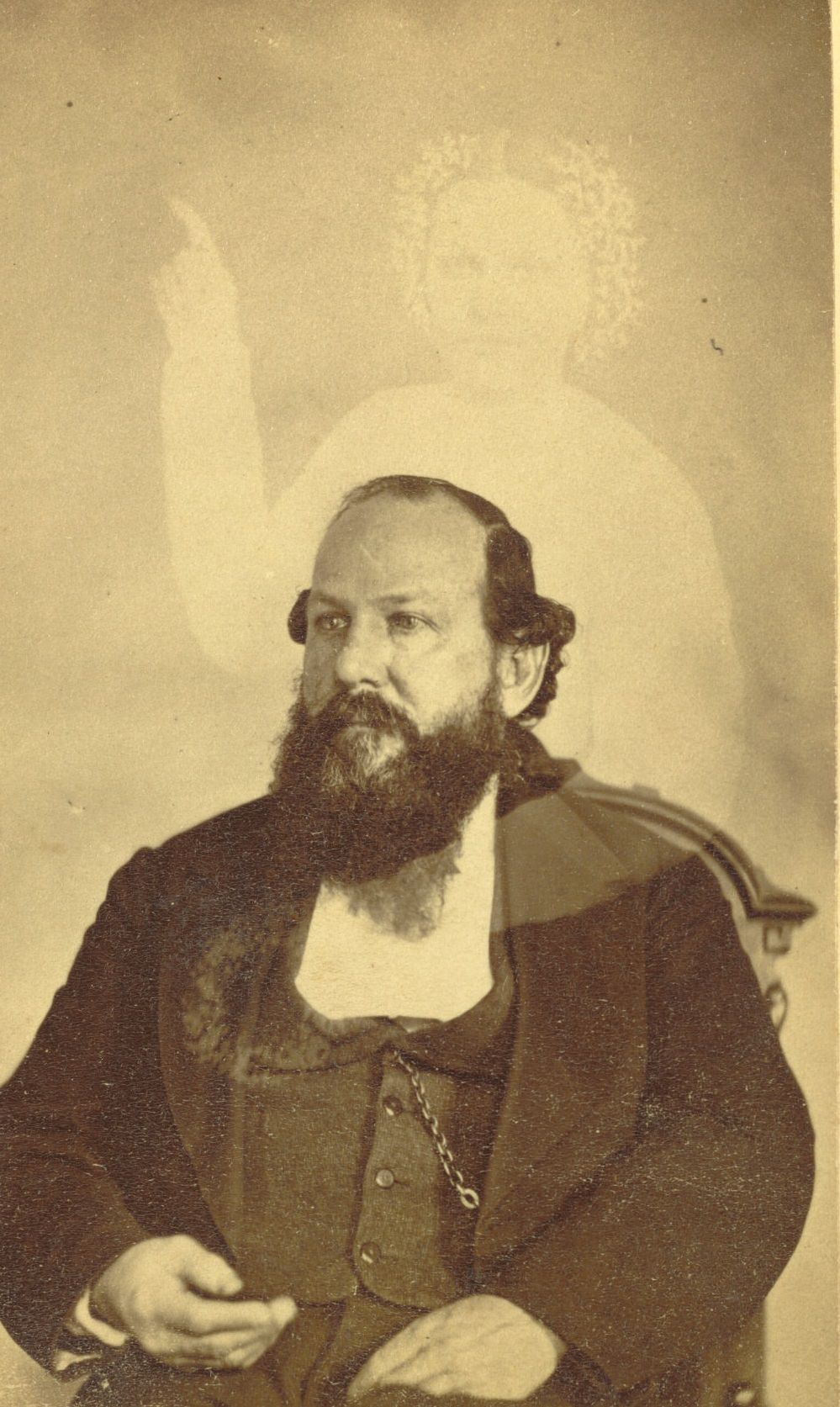

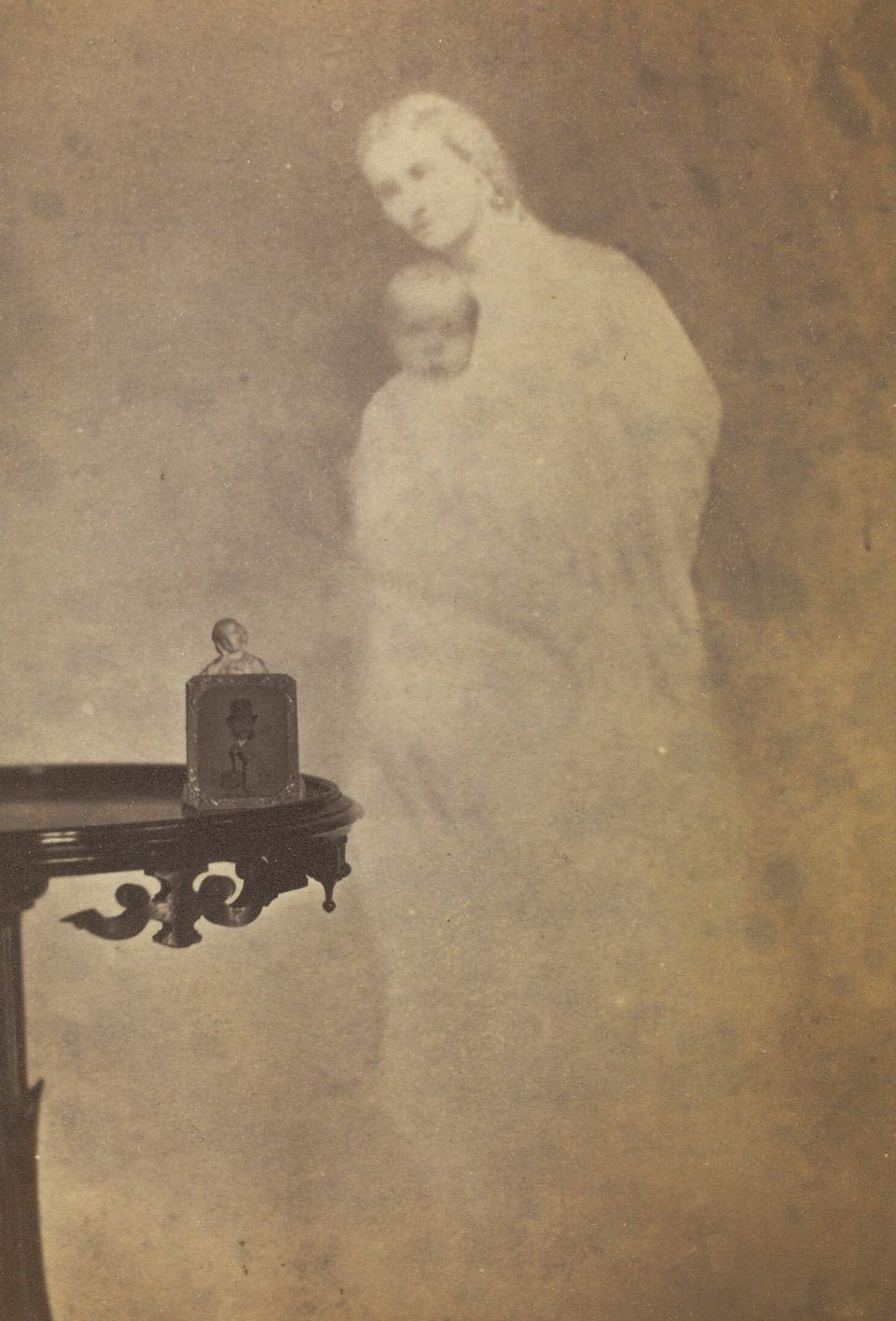

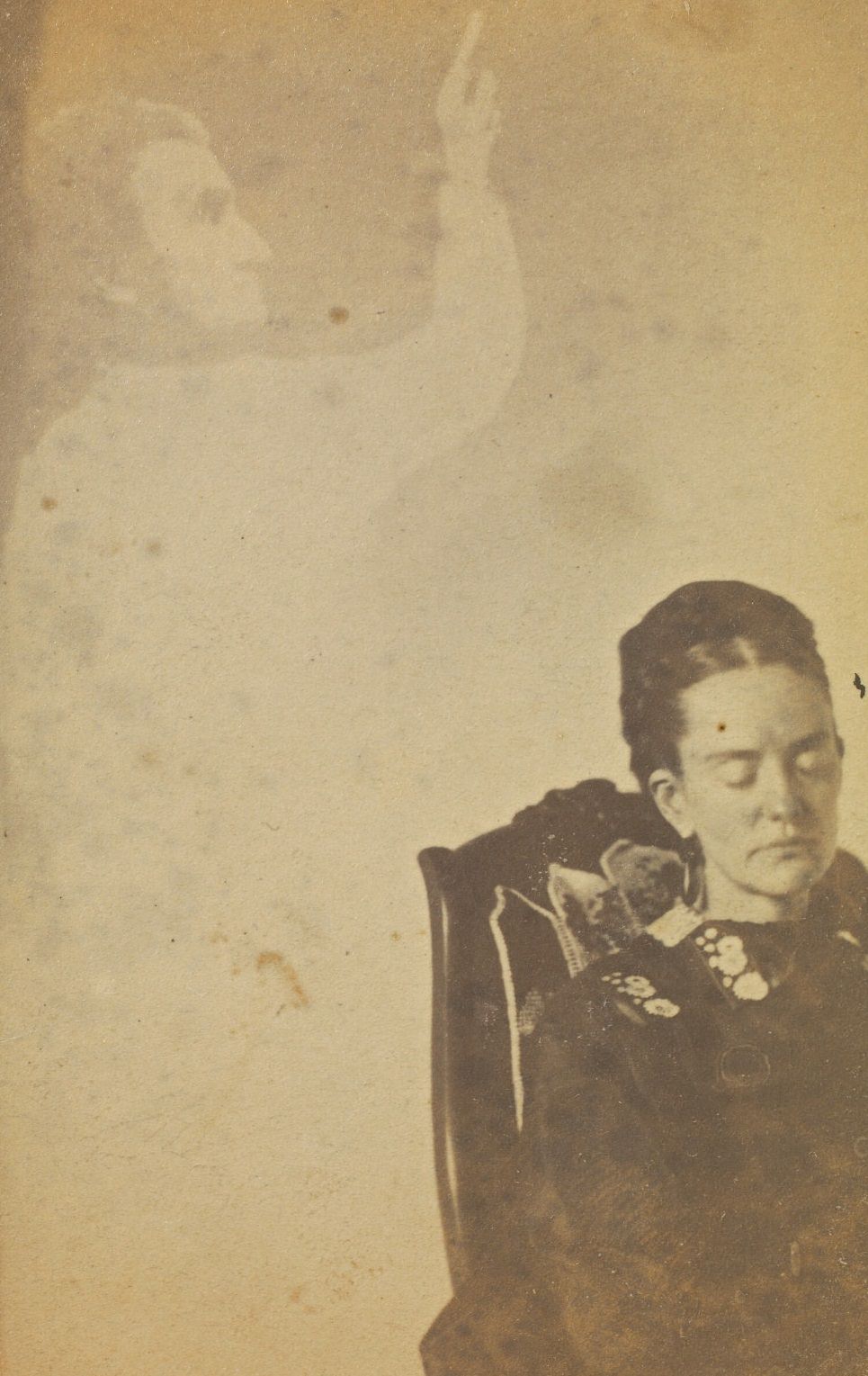

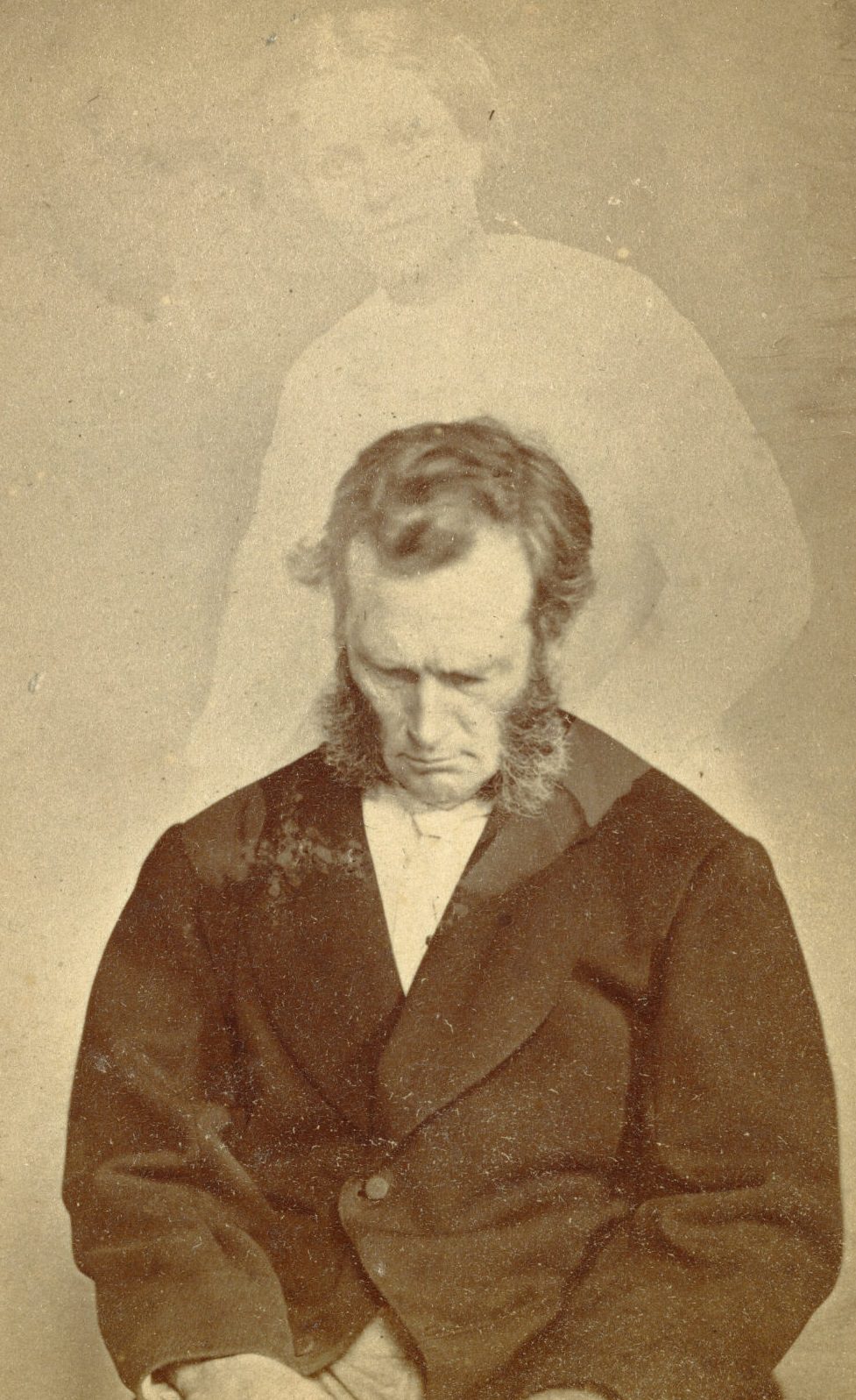

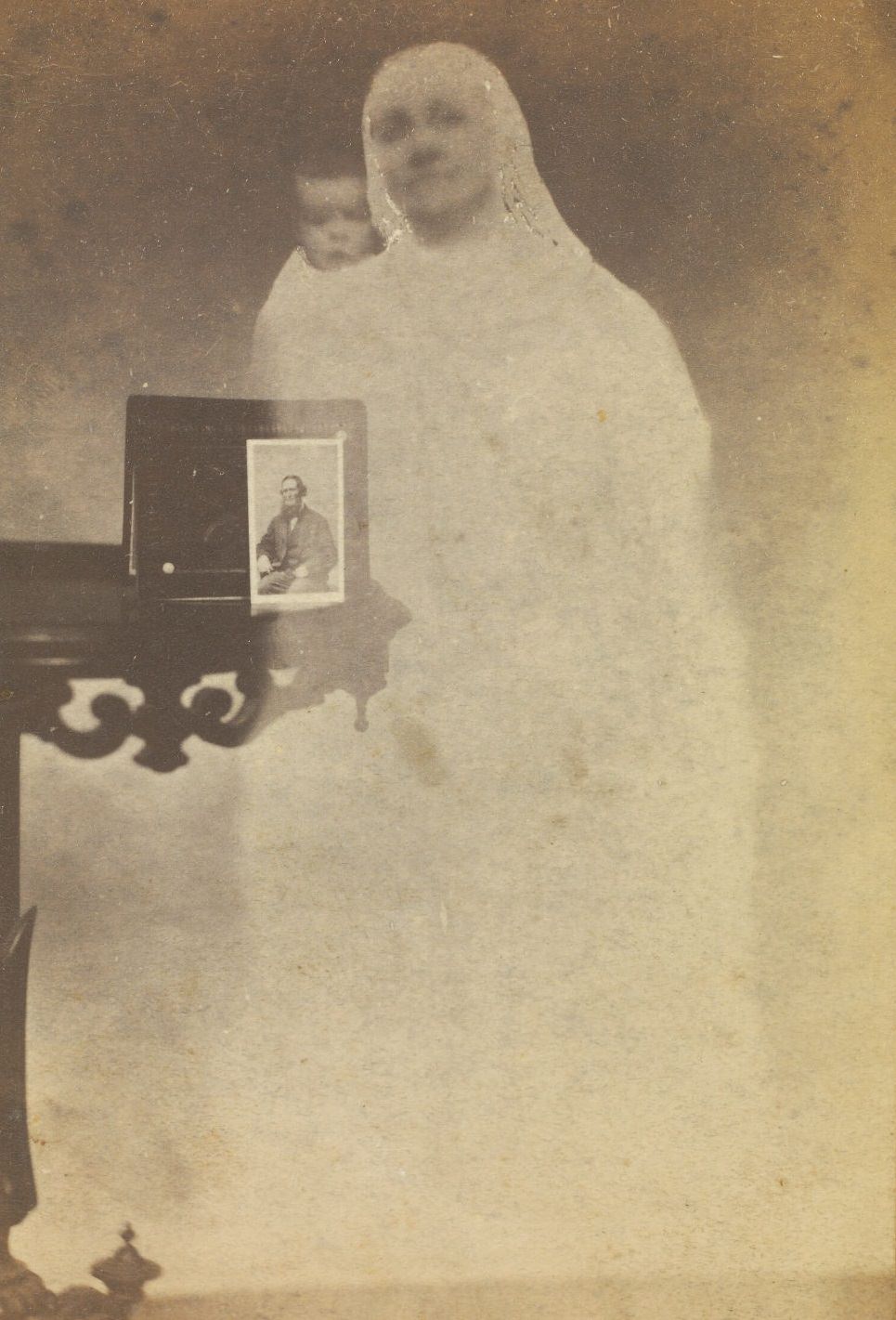

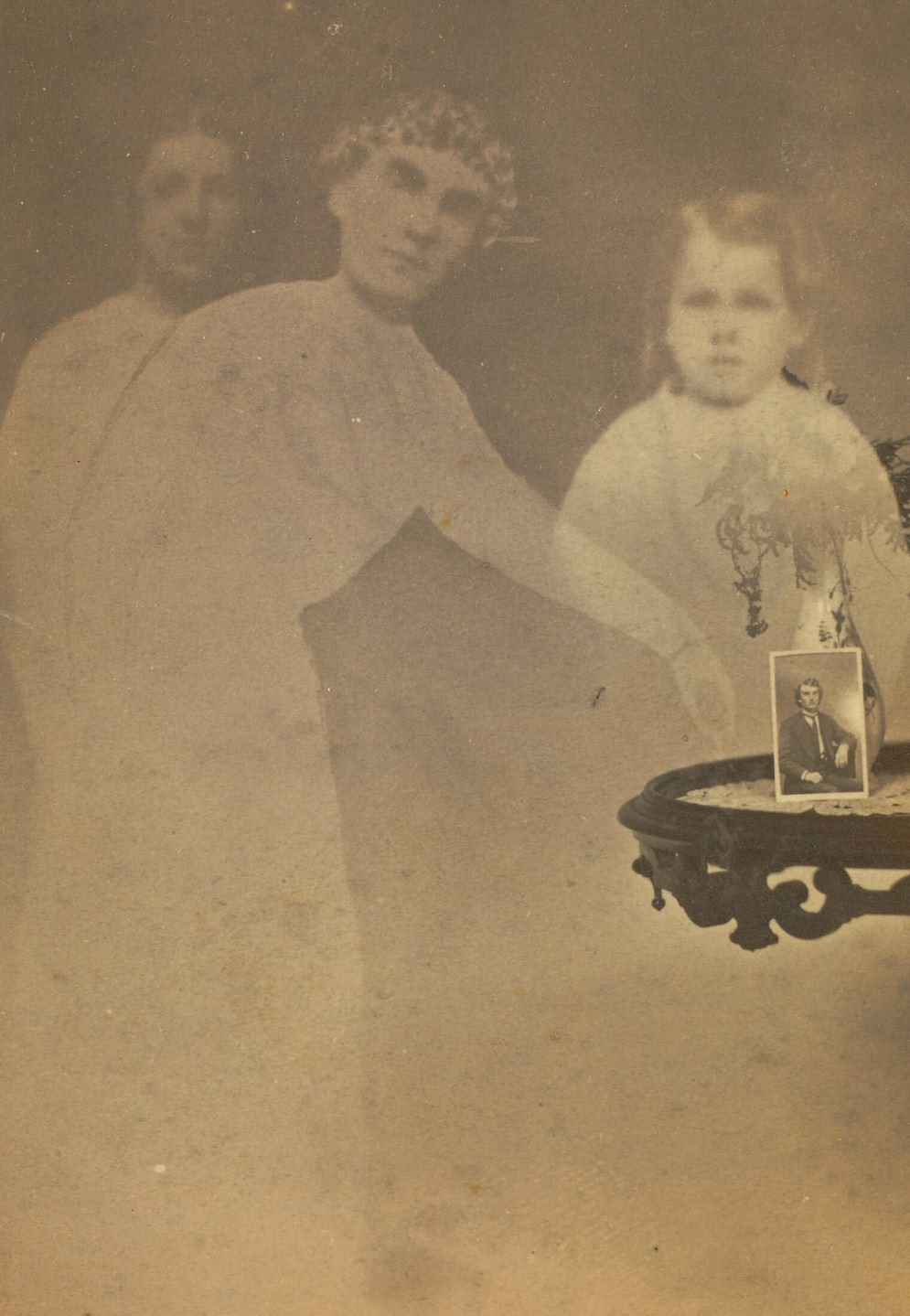

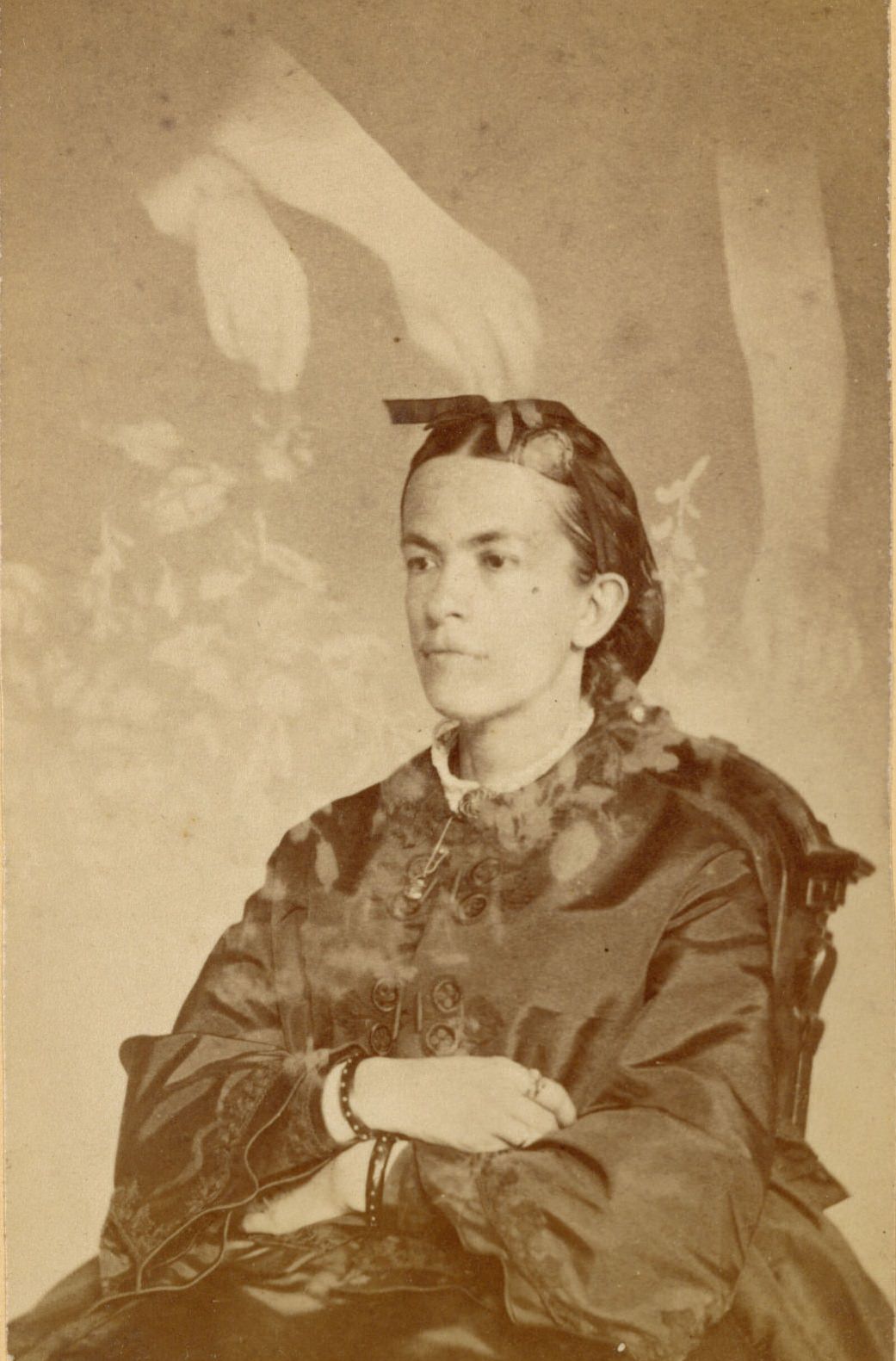

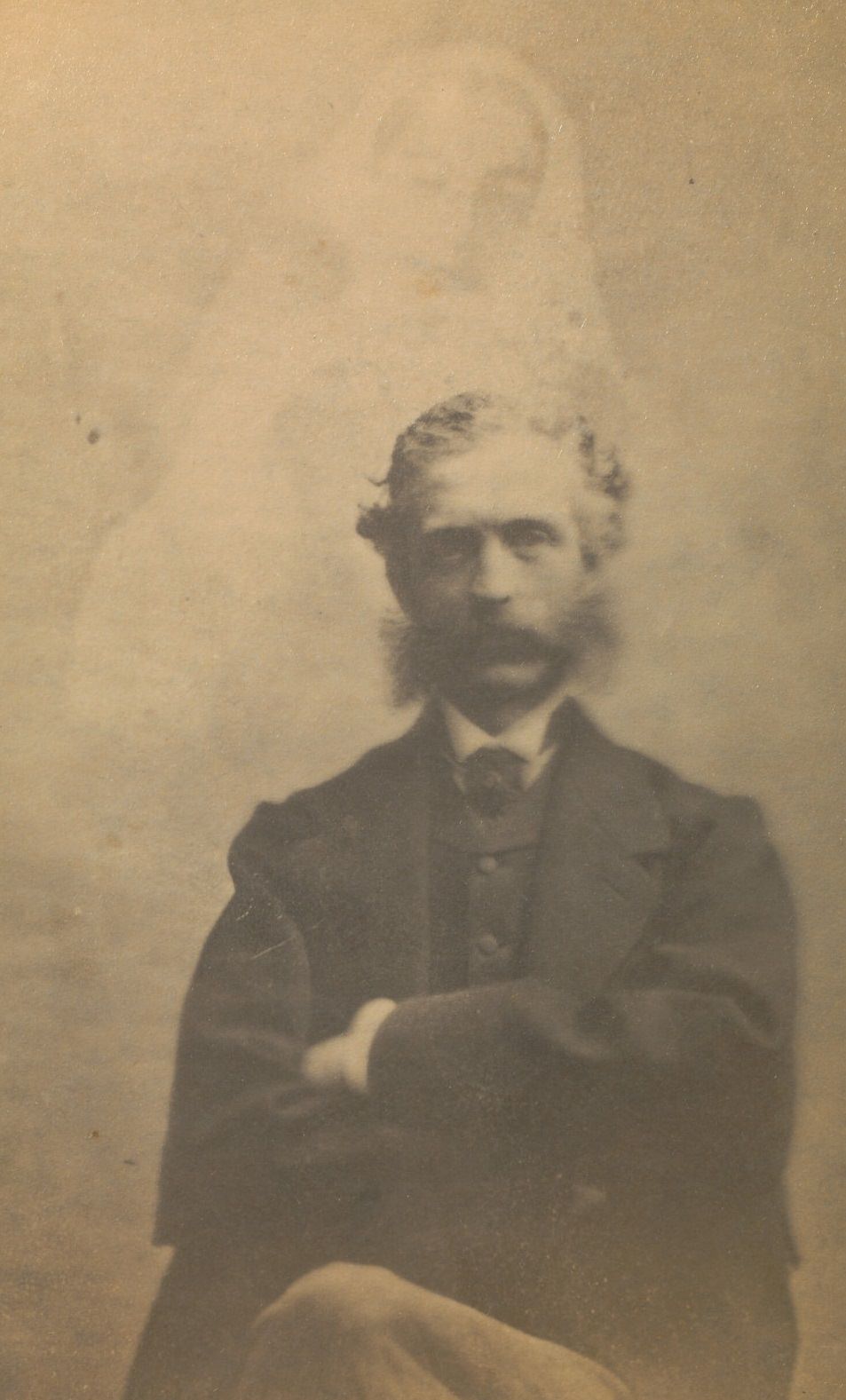

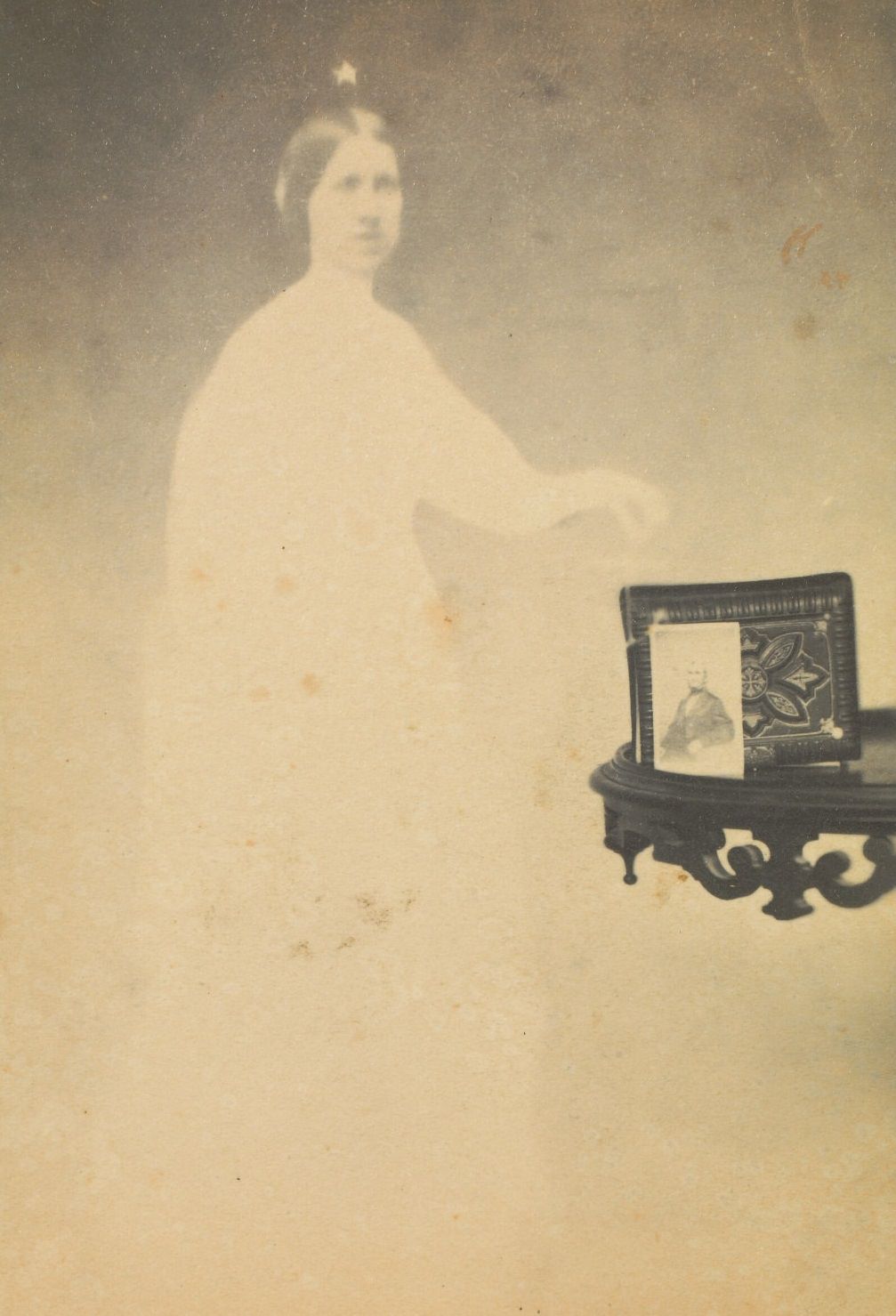

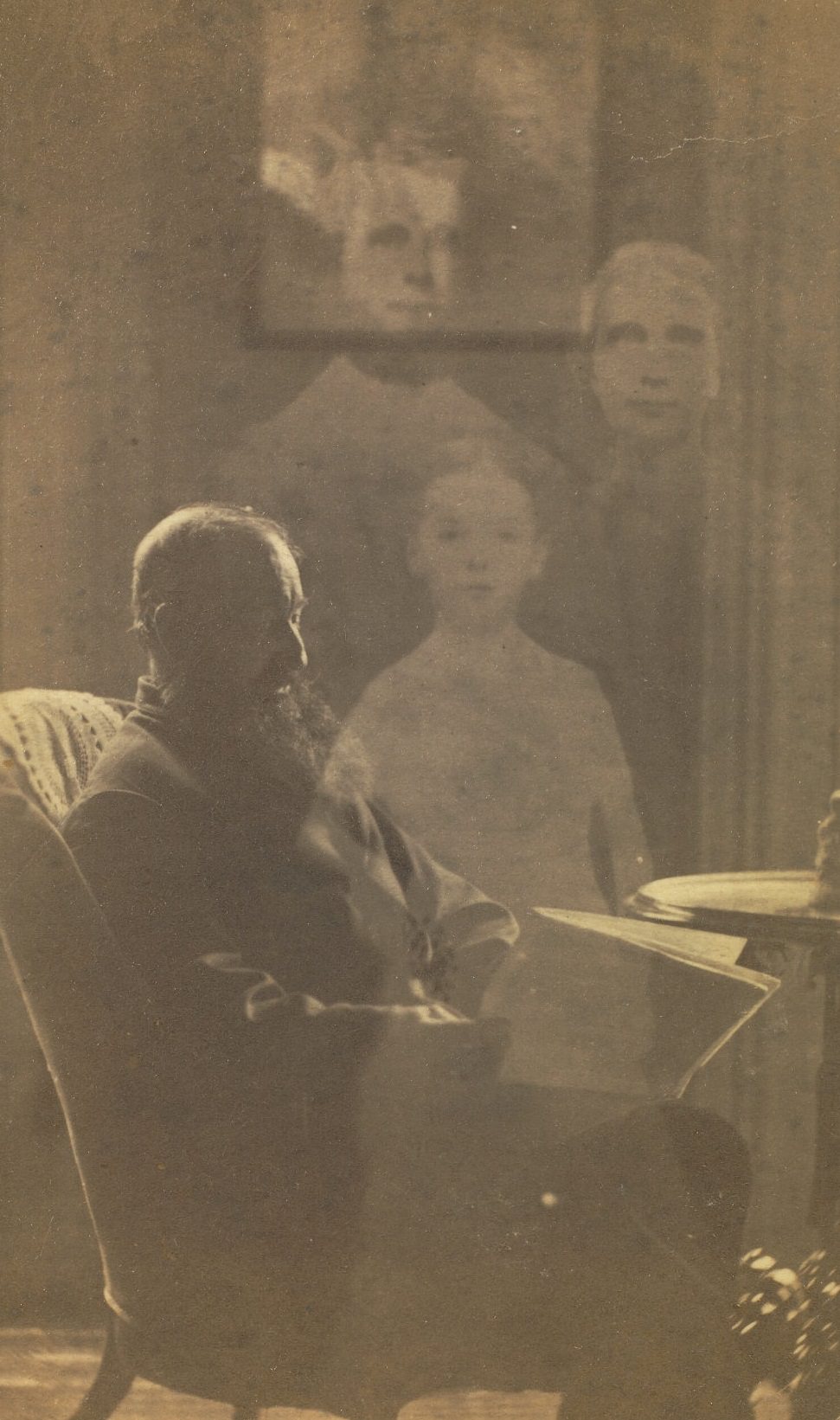

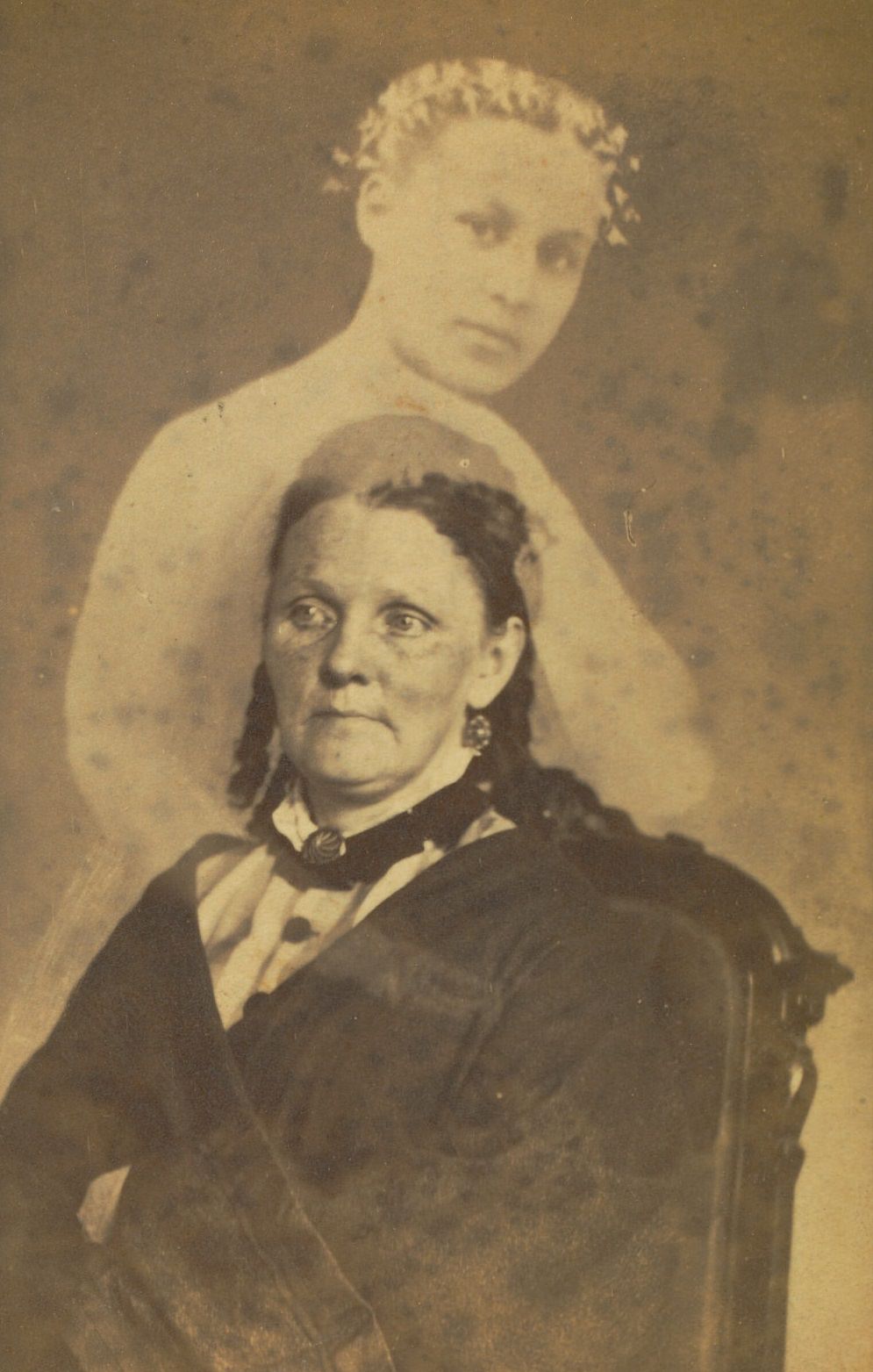

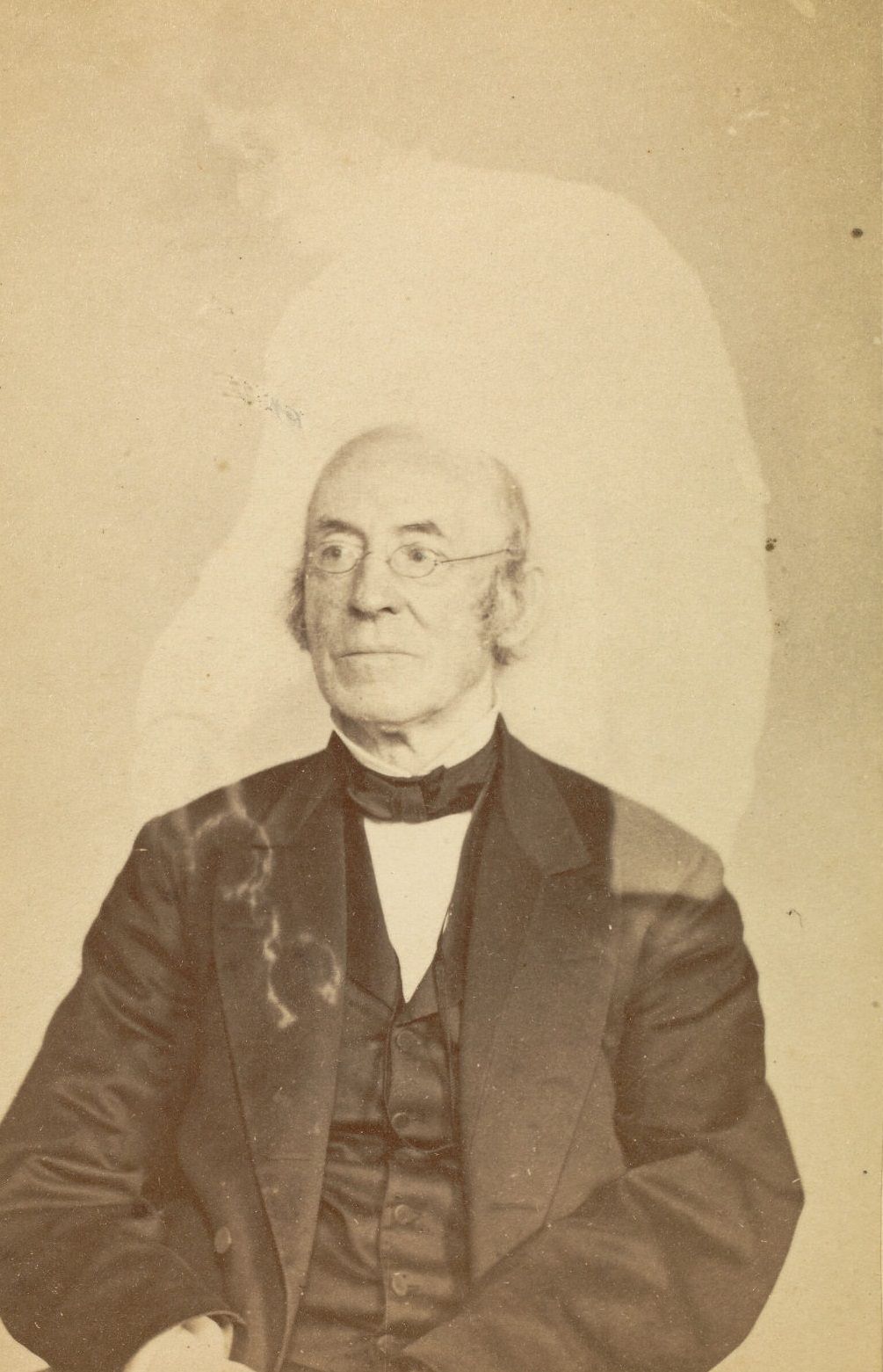

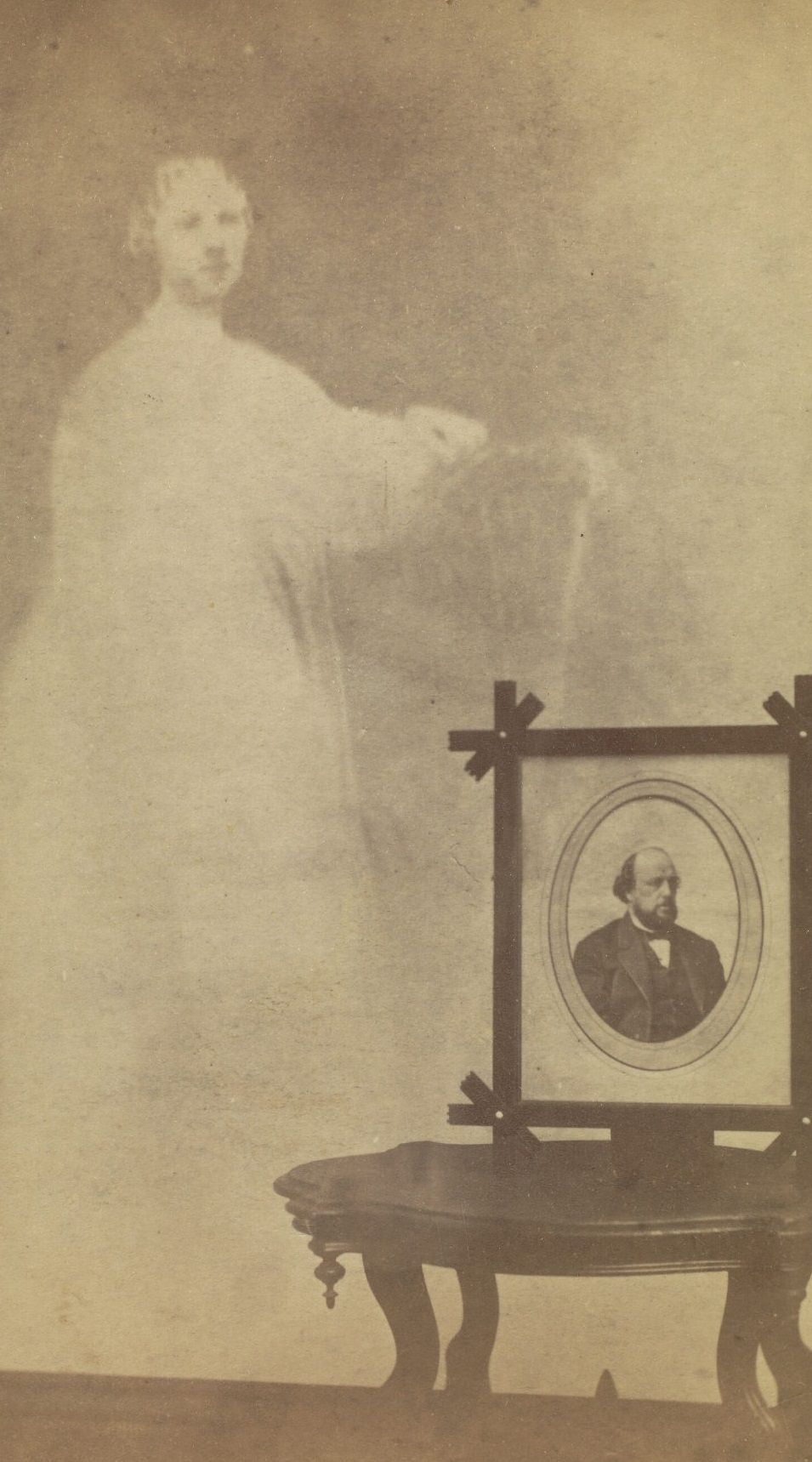

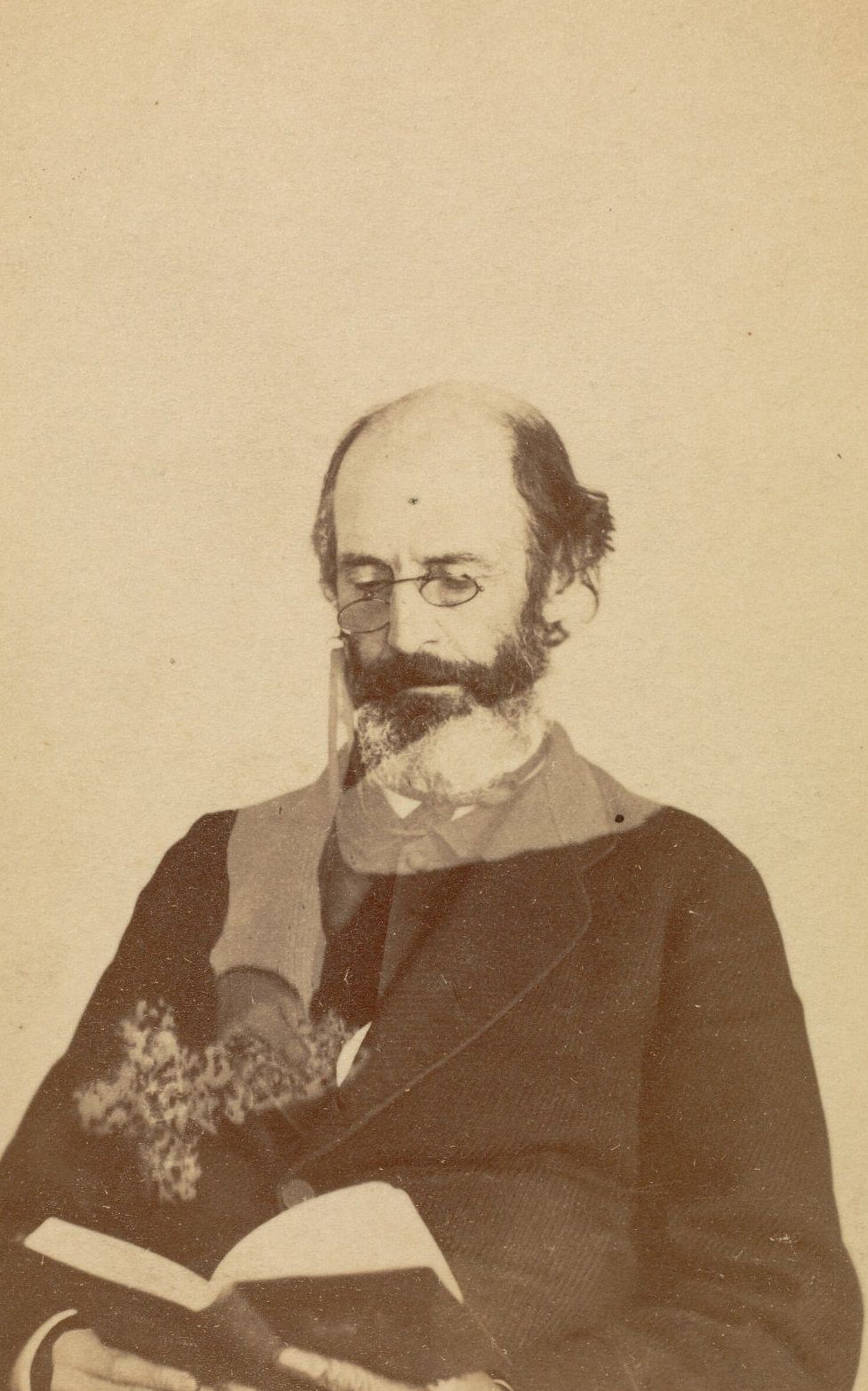

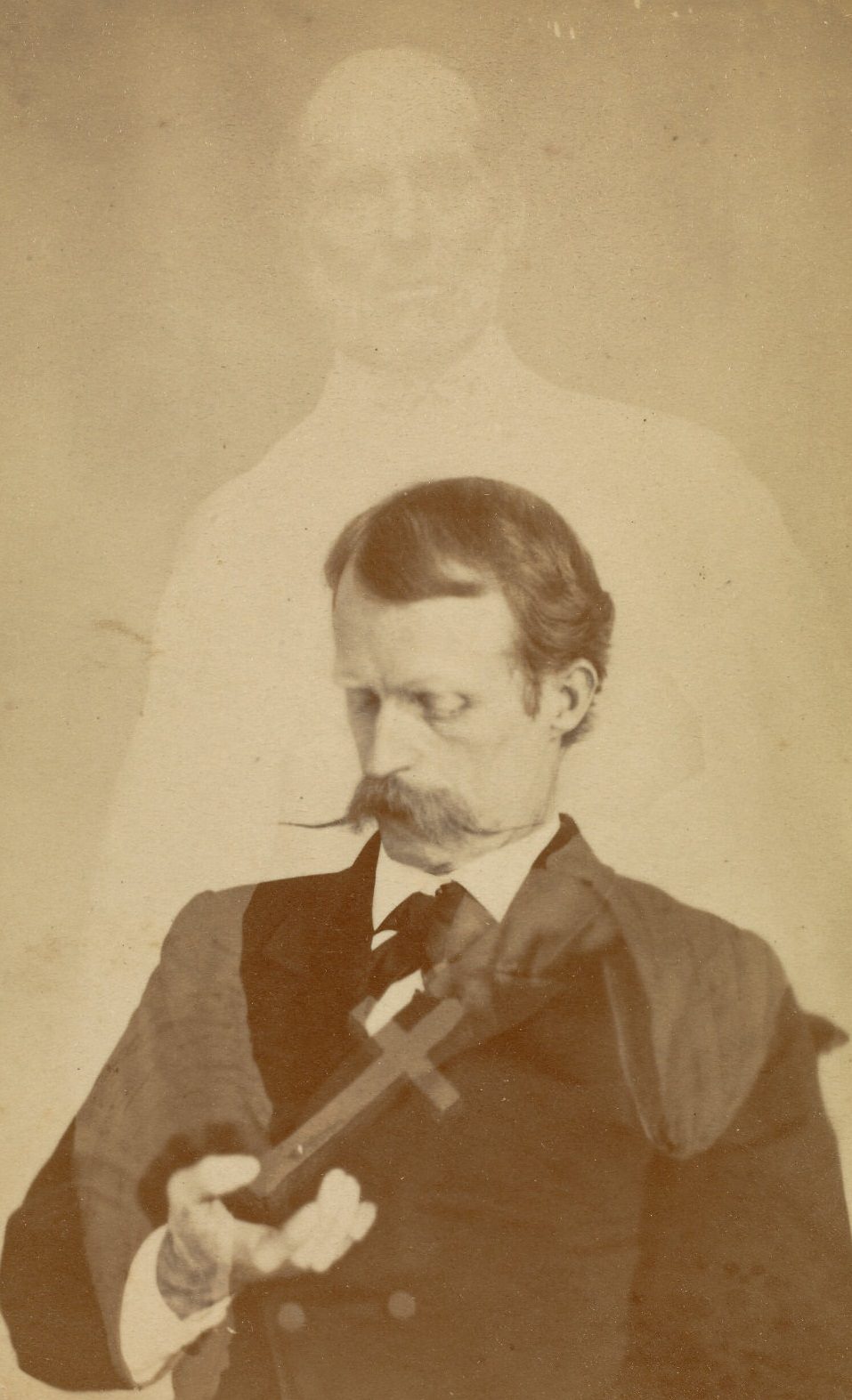

Spiritualists believed the human soul exists beyond the body and that the dead can communicate with the living. After the Civil War, the US gained momentum in this concept developed in the 1850s. Mumler (1832–1884) believed he was capable of photographing the spirits of deceased loved ones. He made ghostly images by incorporating an existing picture of the deceased into a new photograph he took of the surviving relative. Highly publicized civil court trials marked his eight-year-long activity for fraud.

Thousands of families sought reassurance that their loved ones lived on after death through spirit photography due to the vast death toll caused by the American Civil War. Mumler worked as a jewelry engraver in Boston before becoming a spirit photographer. He created a self-portrait that appeared to feature the ghost of a long-dead relative in the early 1860s. This is widely acknowledged as the first spirit photograph, which features the likeness of a deceased person (often a relative) imprinted by the spirit of the deceased. Eventually, Mumler moved to New York City, where his work was analyzed by numerous photography experts, none of whom was able to find any signs of fraud. Mumler became a full-time spirit photographer, working in Boston and eventually moving to New York City.

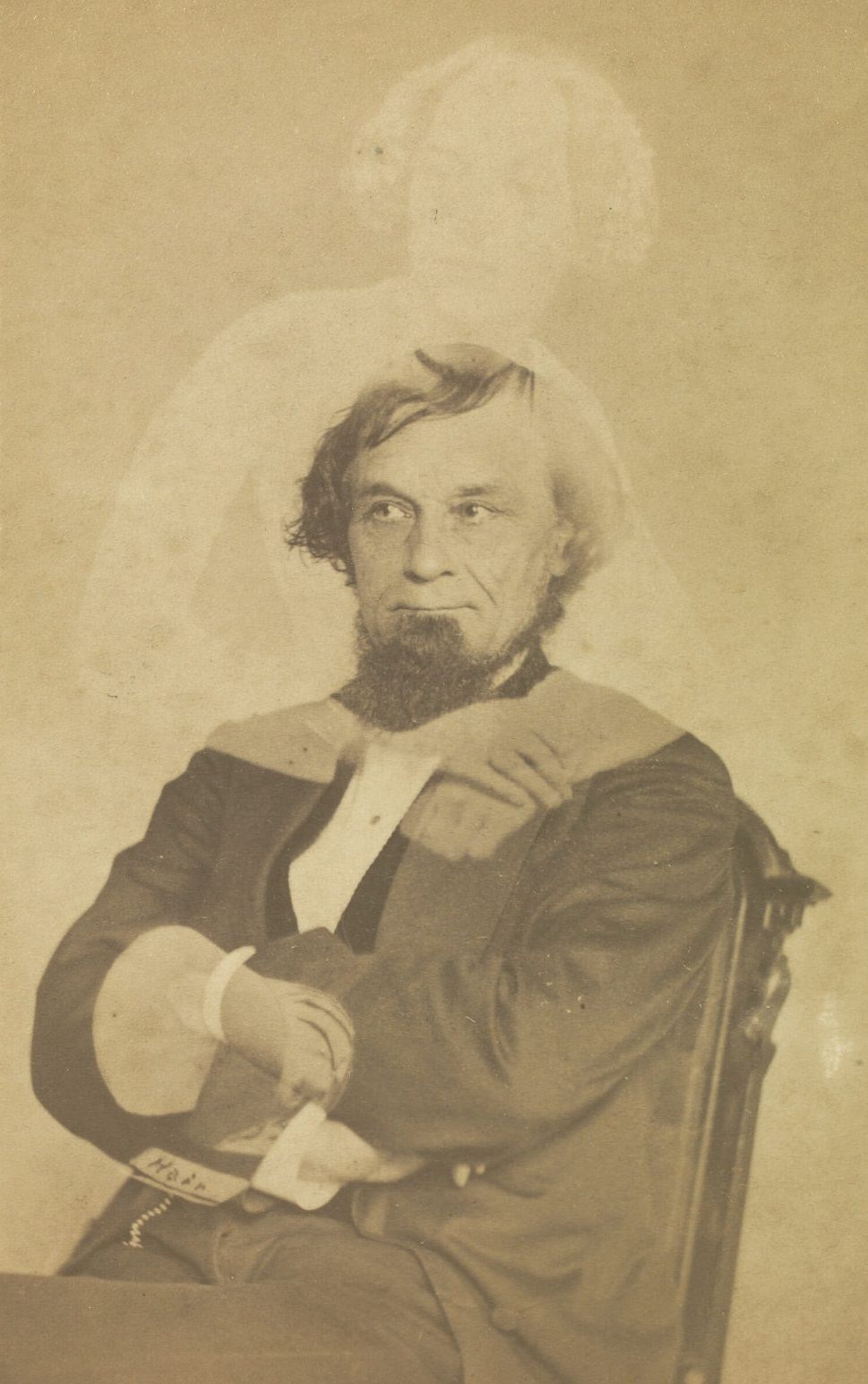

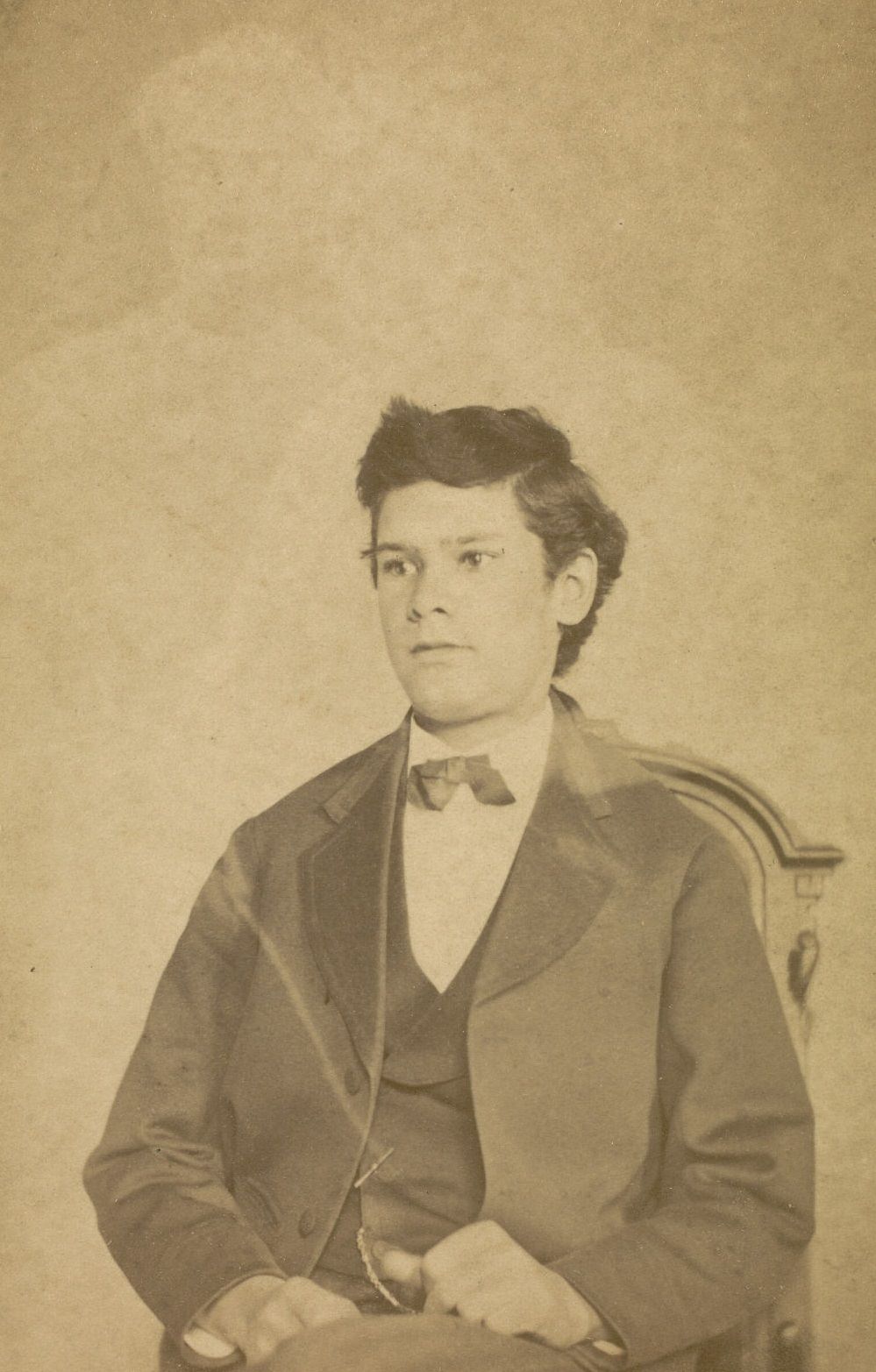

A critic of Mumler’s work was P.T. Barnum, who claimed that Mumler exploited grief-stricken people’s judgment. Mumler had been accused, among many others, of staging ghosts of people who were still living and stealing photos of deceased relatives from houses. Barnum’s accusation was one of many in a chorus of accusations. When people realized that some of the supposed spirits were still alive, he was exposed as a fraud. Mumler was eventually brought to trial for fraud in April 1869. To demonstrate how easy it was to create spirit photographers, Barnum hired Abraham Bogardus to create a photograph that appeared to depict Barnum with Abraham Lincoln’s ghost. Moses A. Dow, a journalist Mumler had photographed, testified in support of Mumler. Mumler was acquitted because the prosecution could not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the photographs were fabricated. As a result of the trial, some sources reported that he died penniless and disgraced, while others claimed that his business took off due to the publicity. After working in photography, Mumler developed a process by which photo-electrotypes could be made and printed as quickly as woodcuts (known as the “Mumler Process”). He died on May 16, 1884, and his obituary briefly mentioned the earlier spirit photography scandal in the last line.