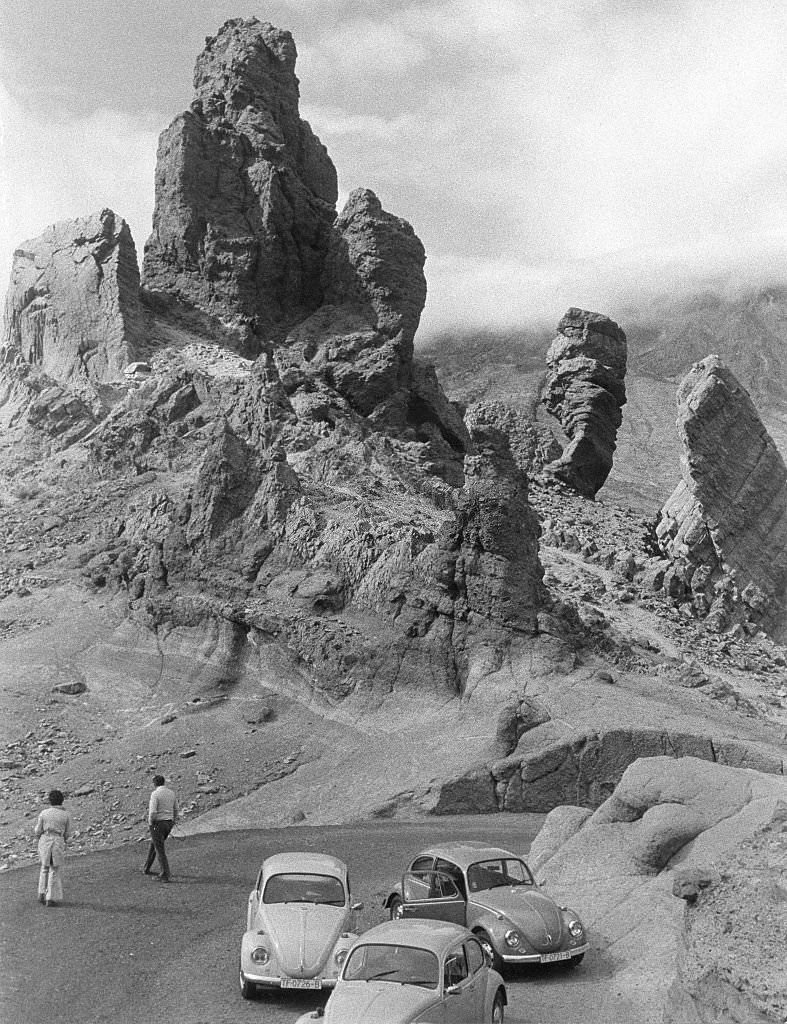

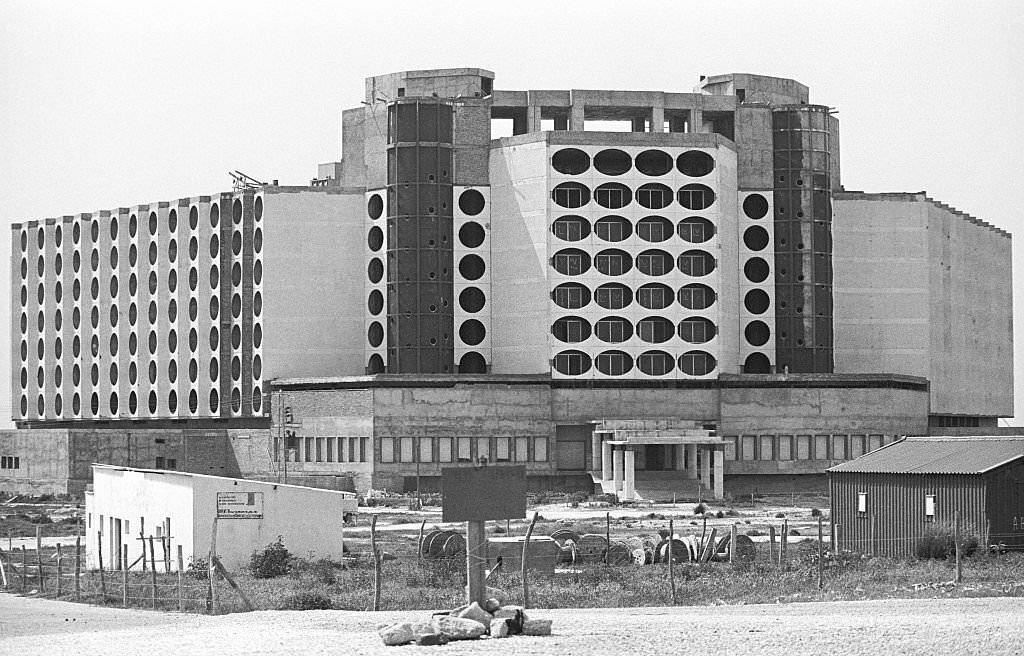

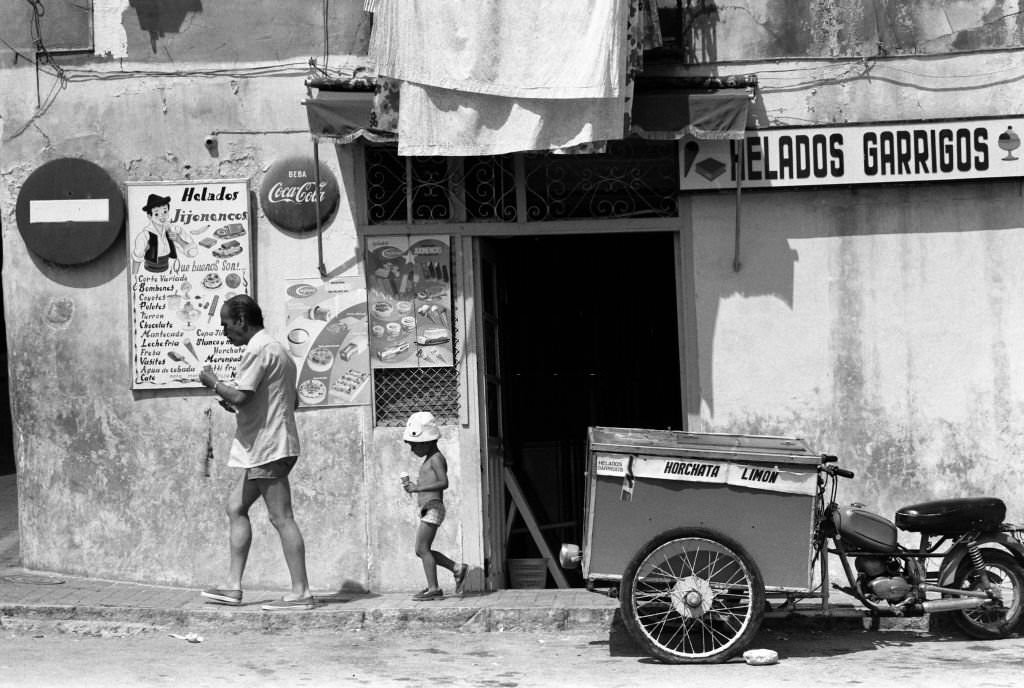

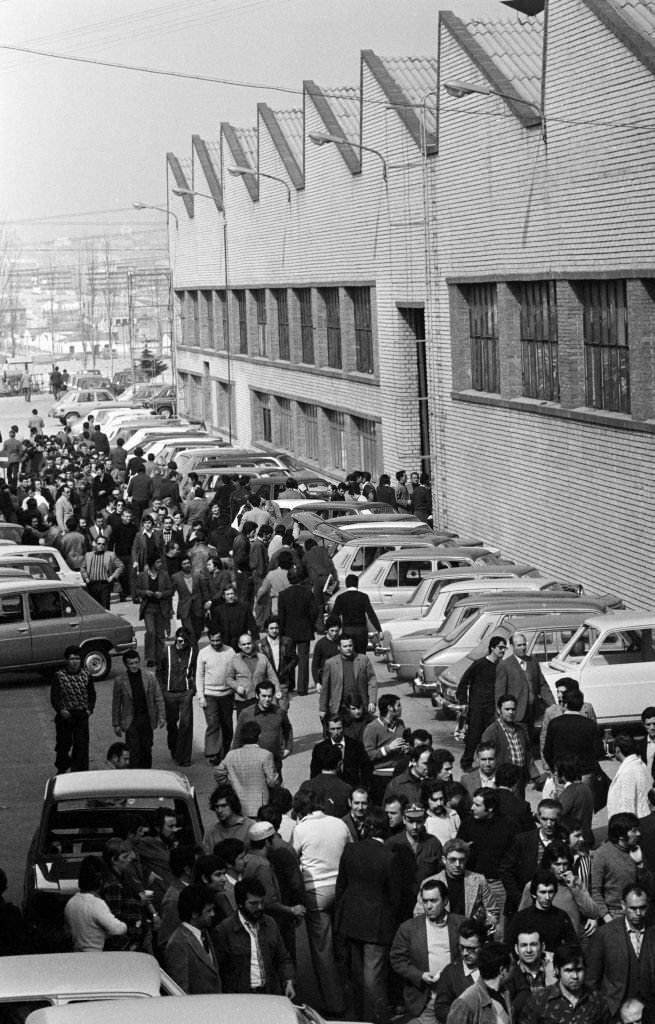

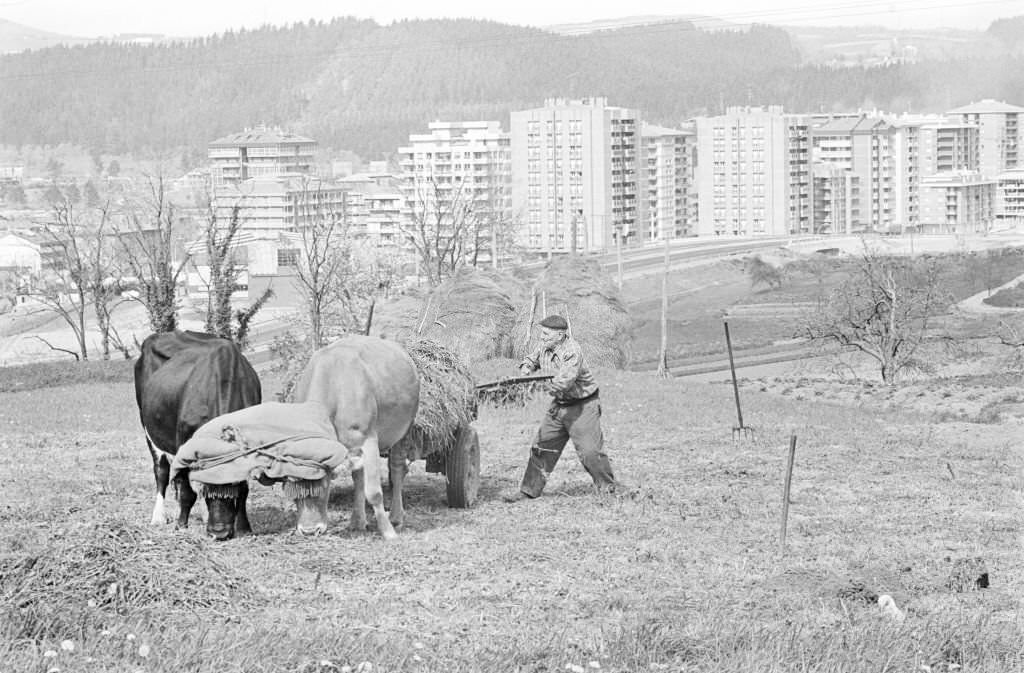

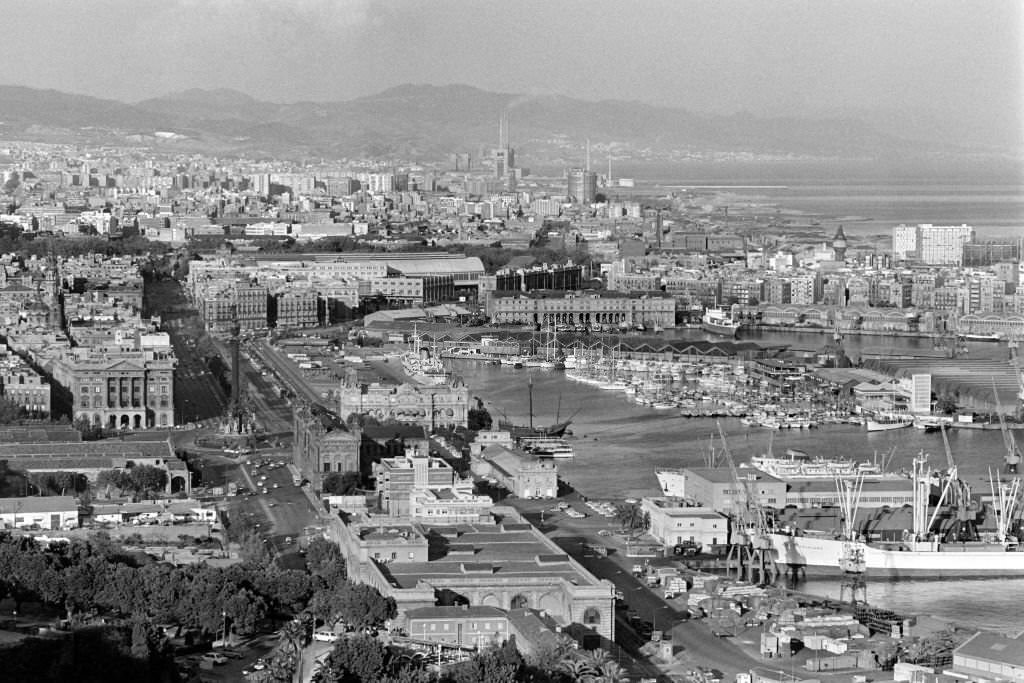

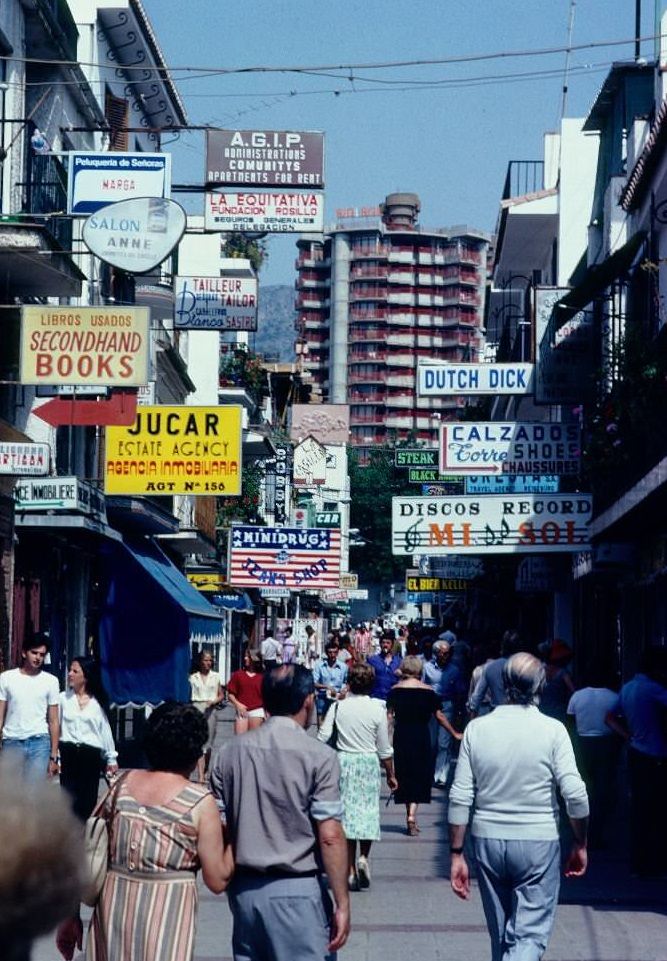

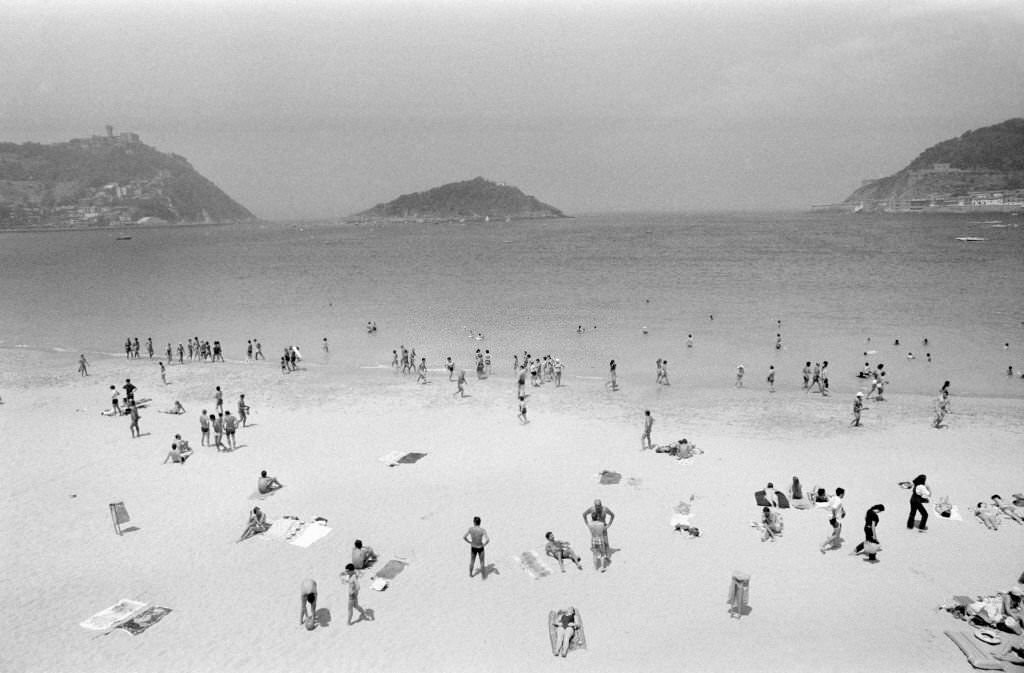

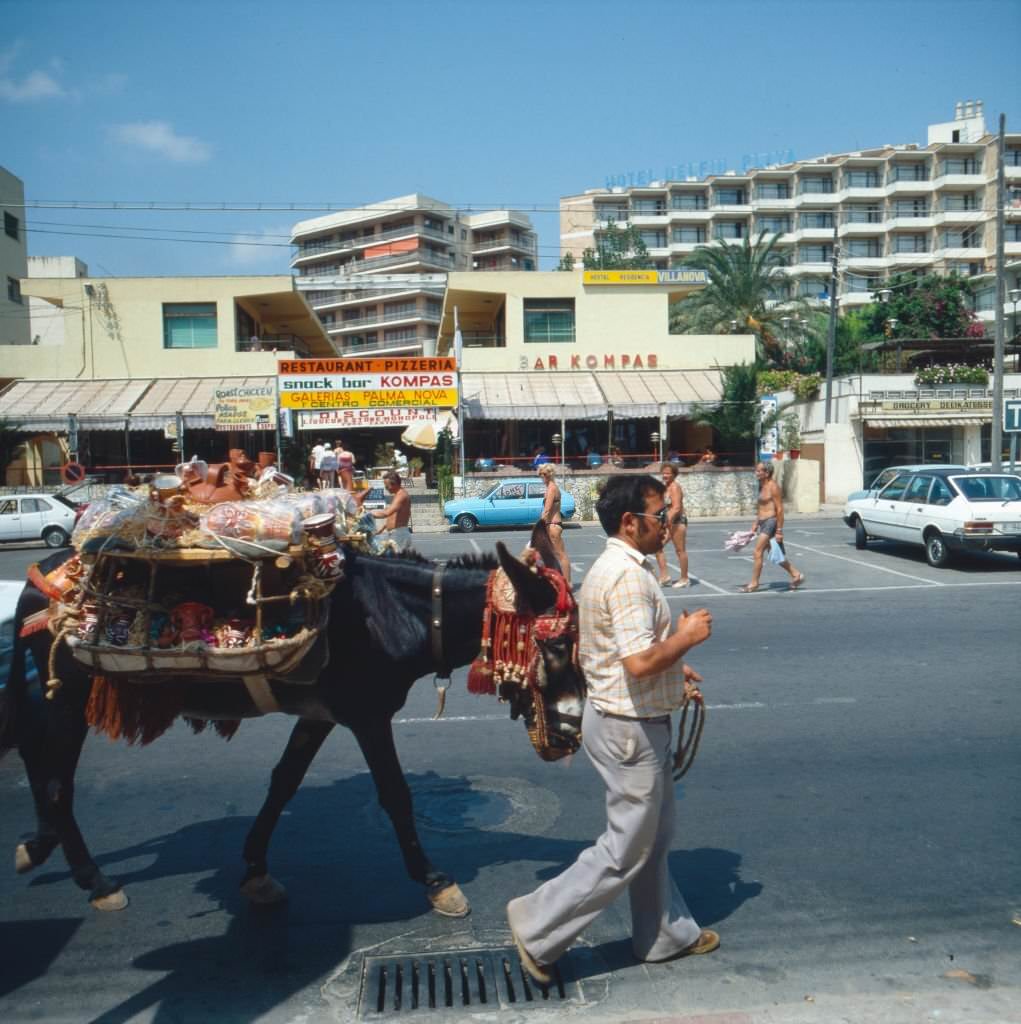

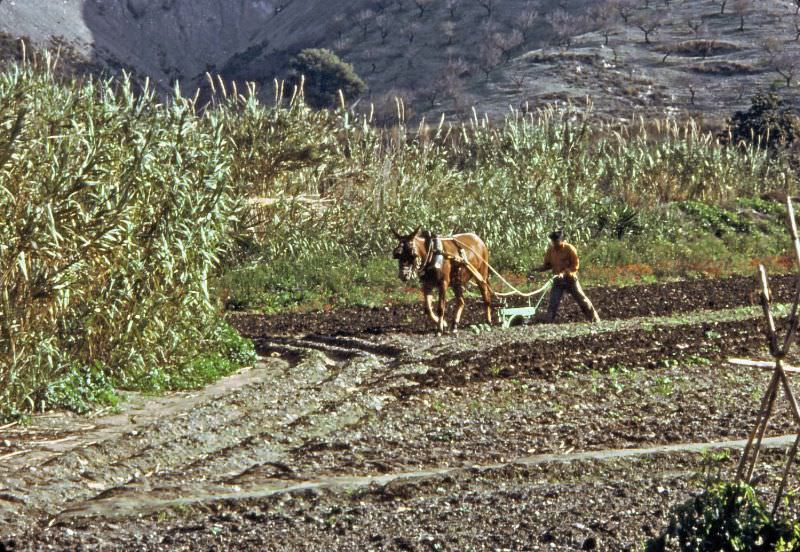

The economic boom of the 1970s had a powerful impact on Spain’s society. People from the countryside moved to those urban areas that provided employment, mainly Madrid, Barcelona, and centers in the Basque Country. As agriculture became more mechanized (the number of tractors in Spain increased sixfold during the boom), many agricultural workers became redundant. Five million Spaniards left the countryside during the 1960s and 1970s because of the need for work and the desire for better living conditions in urban areas. Around one million moved to other Western European countries. By the mid-1970s, some areas of Extremadura and the high Castilian plateau appeared nearly depopulated due to migration.

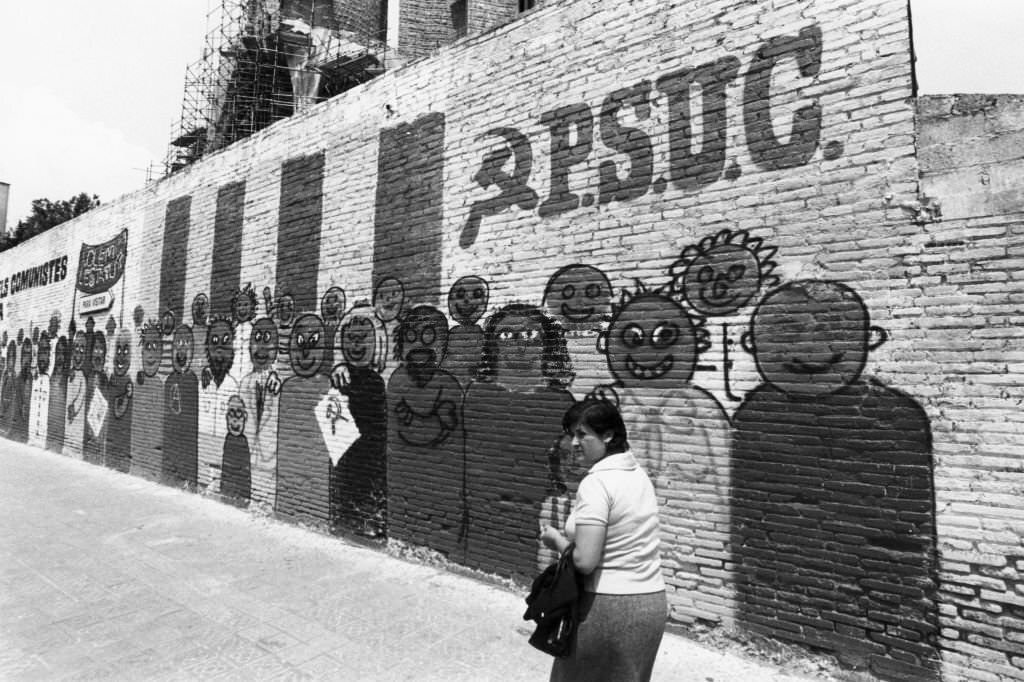

In the 1970s, cities grew at an annual rate of 2.4 percent, and as early as 1970, migrants accounted for 26 percent of Madrid’s population and 23 percent of Barcelona’s. The rate of mass migration slowed substantially after the mid-1970s, and some of the largest urban areas even saw a slight decline in population in the 1980s.

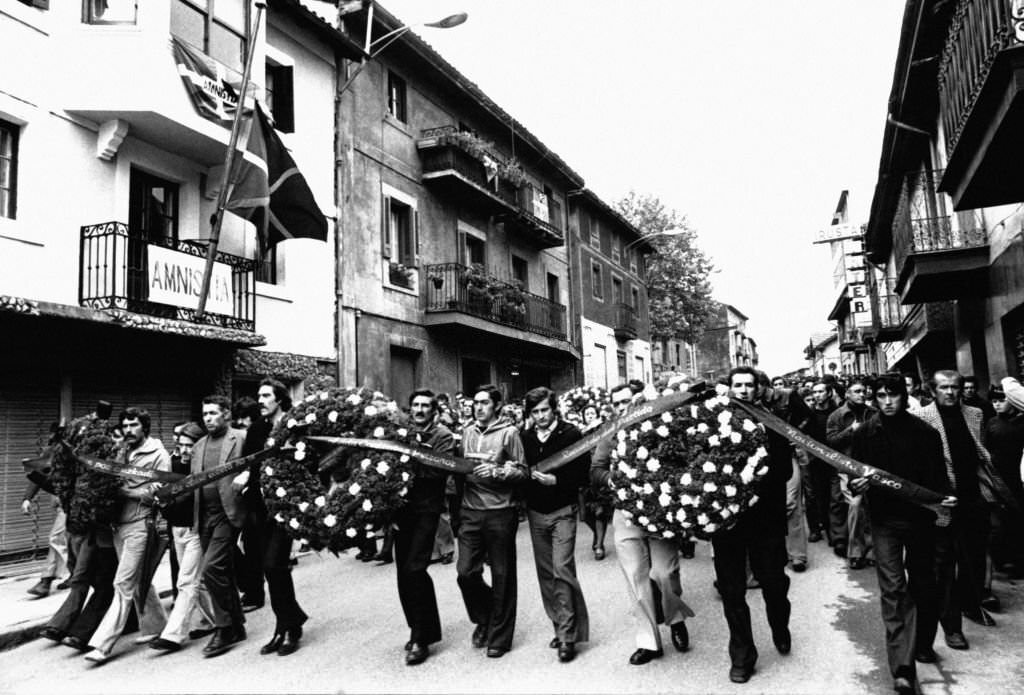

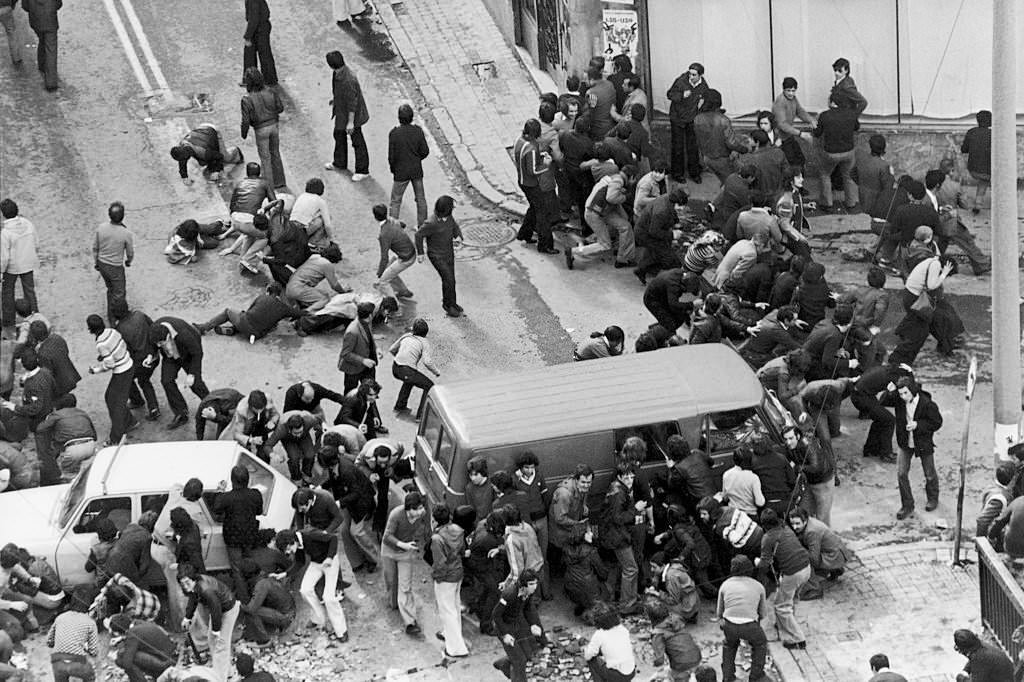

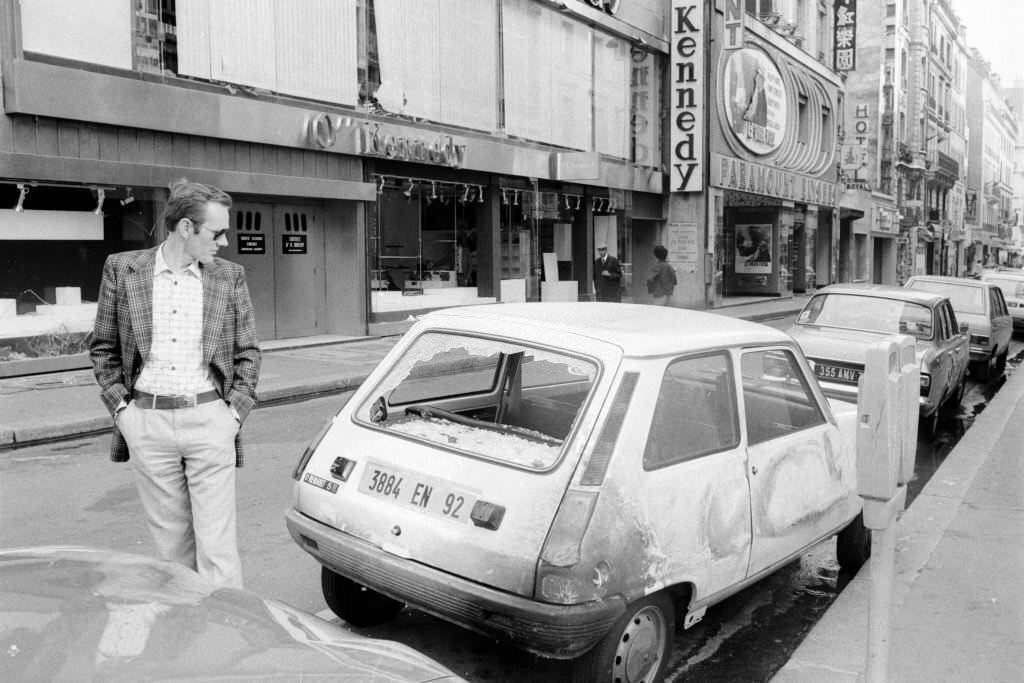

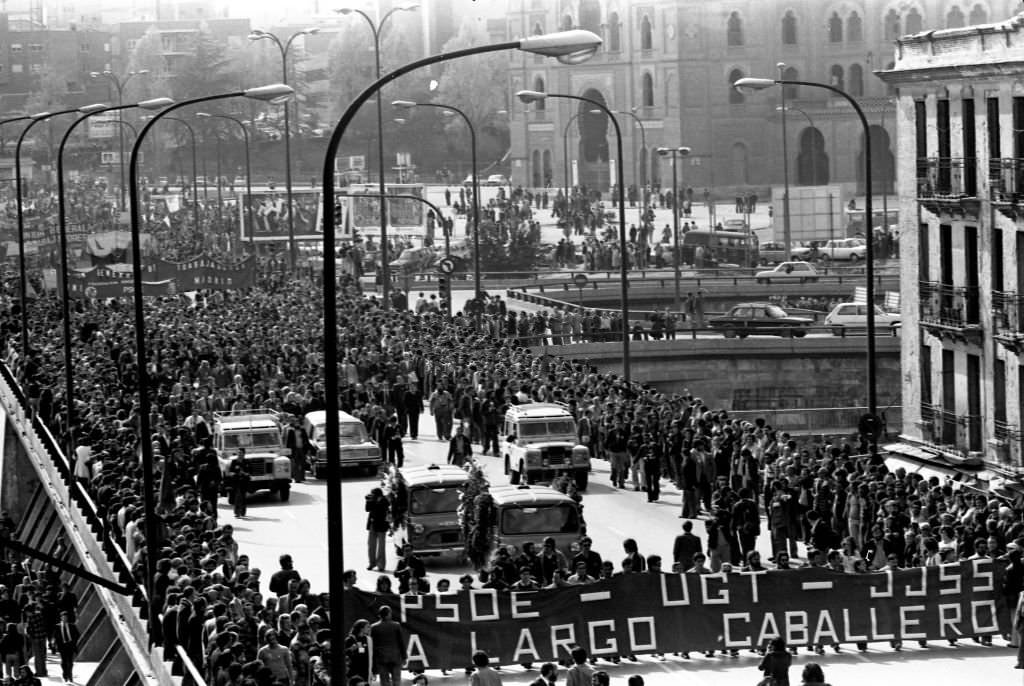

During the early 1970s, Basque Fatherland and Freedom, a revolutionary Basque nationalist group, faced the most virulent opposition from the Franco regime. In order to gain recognition for its demands for regional autonomy, this extremist group used terror tactics and assassinations. ETA’s most daring act was the assassination of Franco’s first prime minister, Luis Carrero Blanco, in December 1973. Carrero Blanco had embodied hard-line Francoism and was considered the person who would continue Caudillo’s policies. Franco’s assassination precipitated the regime’s most serious governmental crisis and disrupted his continuity plans.

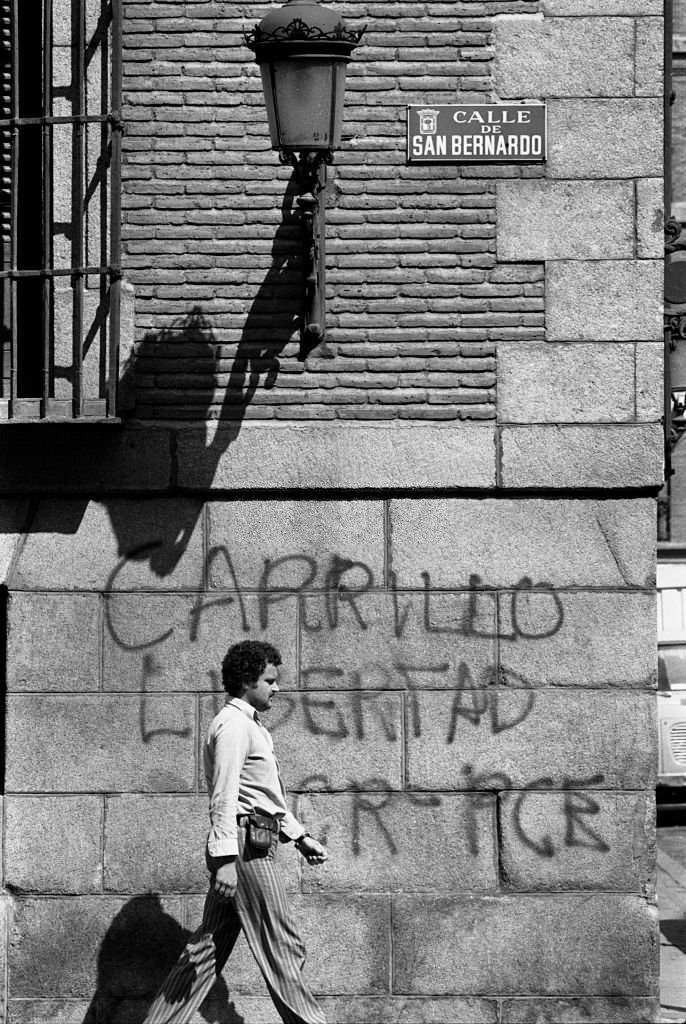

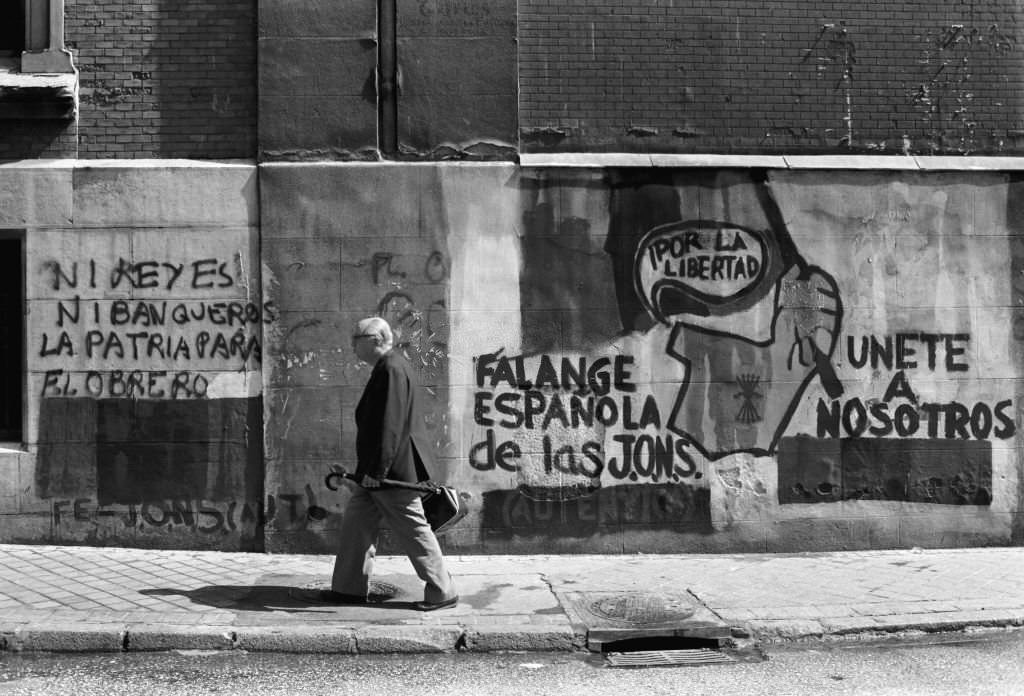

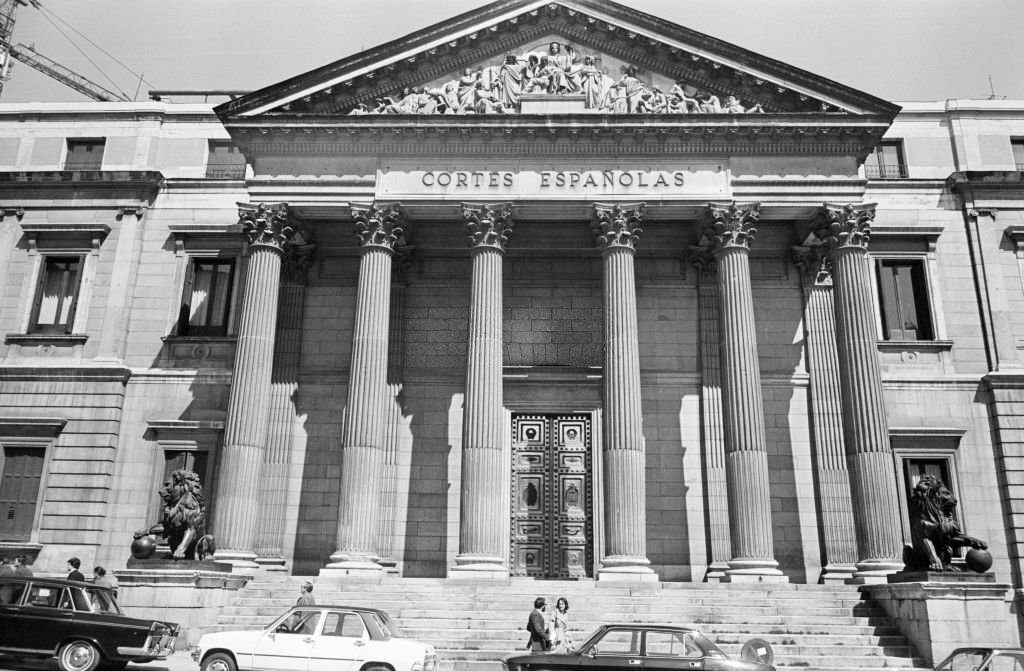

Despite Carrero Blanco’s death, the mounting tensions within Franco’s regime made the continuation of the regime untenable. Carrero Blanco had been plagued by conflict between reactionary elements and those willing to open the door to reform. The conflict continued under Carlos Arias Navarro. The New Prime minister promised to liberalize reforms, including the right to form political associations, in his first speech to the Cortes on February 12, 1974; however, diehard Francoists on the right, who equated any change with chaos, and radical reformers on the left, who wouldn’t accept anything less than a complete break with the past, condemned Arias Navarro.