In the history of espionage, few incidents capture the imagination as vividly as the discovery of the Great Seal Bug – a pivotal event that unfolded during the tension-fraught Cold War era. This episode wasn’t just a feat of secret intelligence; it was a stark demonstration of the lengths nations would go to for gathering information, marking a significant moment in U.S.-Soviet relations.

The Stage and the Players

As World War II drew to a close in 1945, the landscape of international relations was changing. The Soviet Union and the United States, erstwhile allies against the Axis powers, found their ideologies on a collision course. Trust was threadbare, and mutual suspicion was building, a scenario that set the stage for the Cold War.

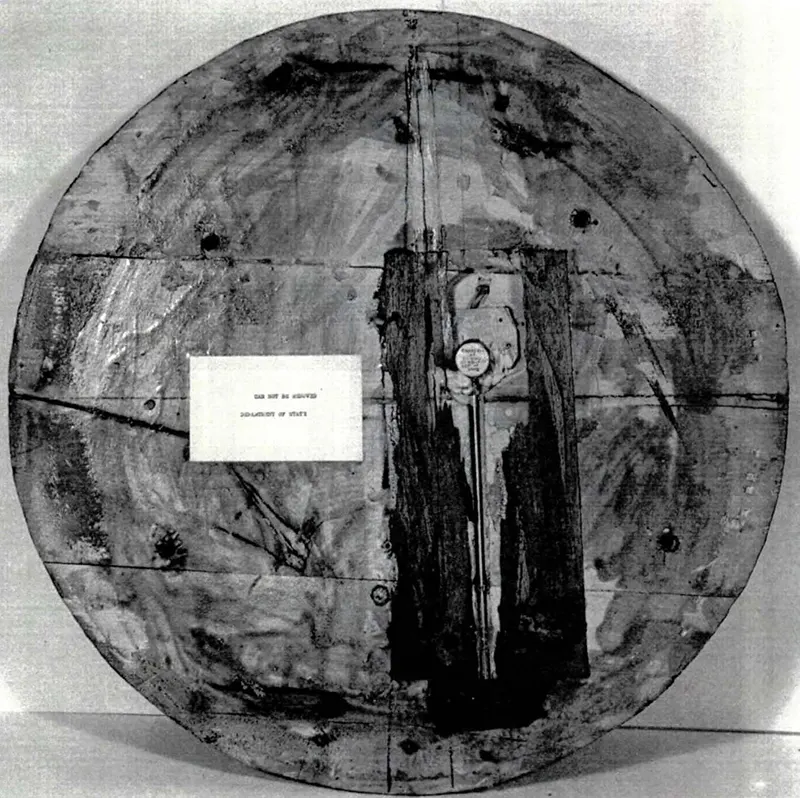

In this atmosphere of burgeoning distrust, an event seemingly unrelated to the world of espionage took place: the presentation of a carved wooden Great Seal to U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman. It was a gift from the Young Pioneer organization of the Soviet Union, a gesture that appeared to symbolize the possibility of peace and friendship between the two global powers. Ambassador Harriman, suspecting nothing amiss, graciously accepted the gift, and the plaque took a place of pride within the study of his Moscow residence.

An Ingenious Plan Unfolds

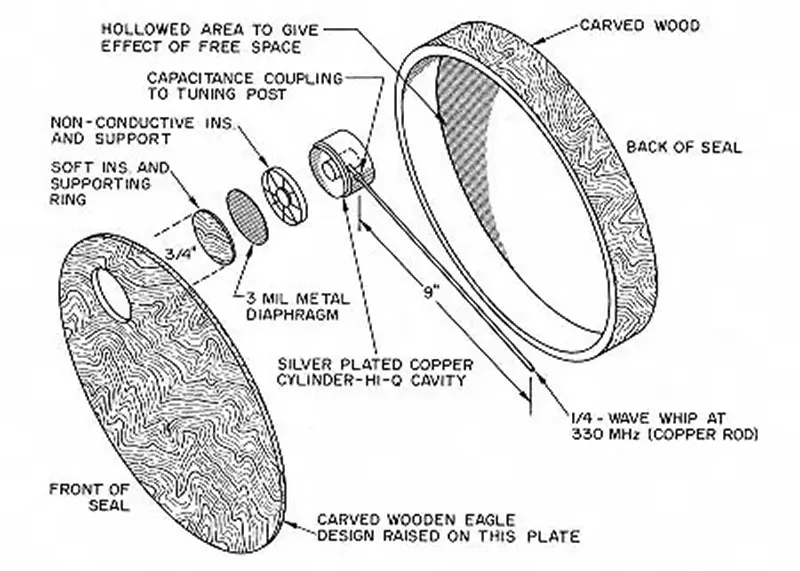

The truth of the Great Seal gift was far more insidious. The Soviets, under the directive of the notorious Lavrentiy Beria, head of the secret police, had conceived a daring plan to bug the Ambassador’s residence. The execution of this plan fell to the brilliant inventor Léon Theremin. Unlike standard listening devices of the time, which required their power source and regular maintenance, Theremin’s creation was a marvel of espionage technology.

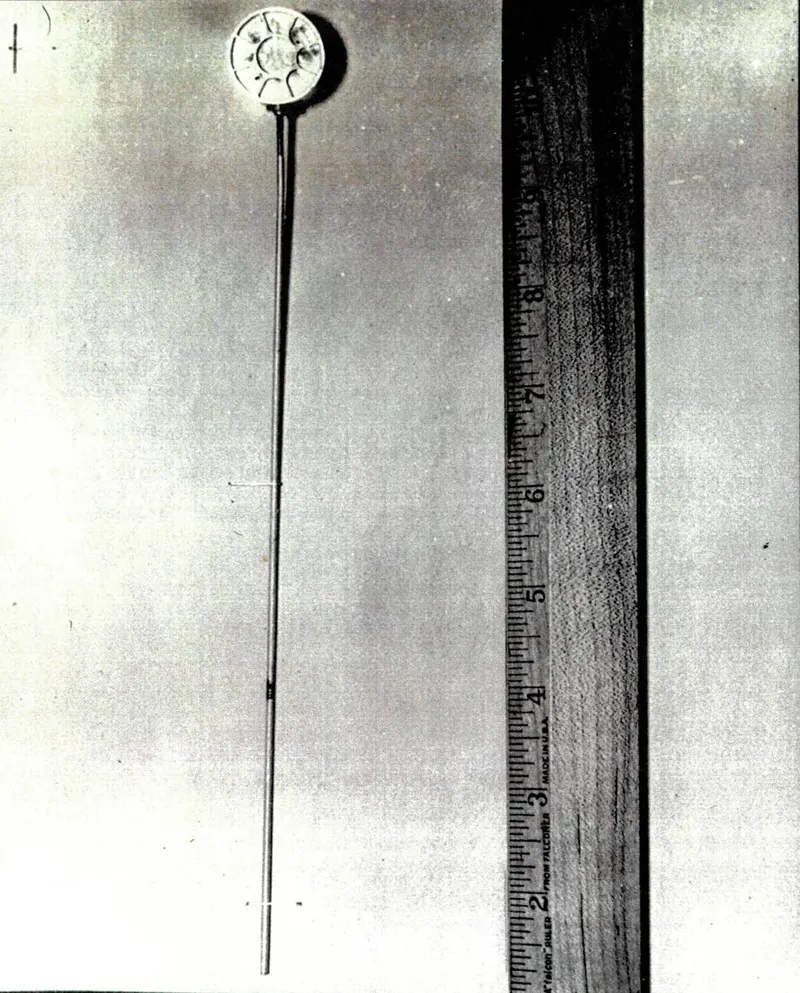

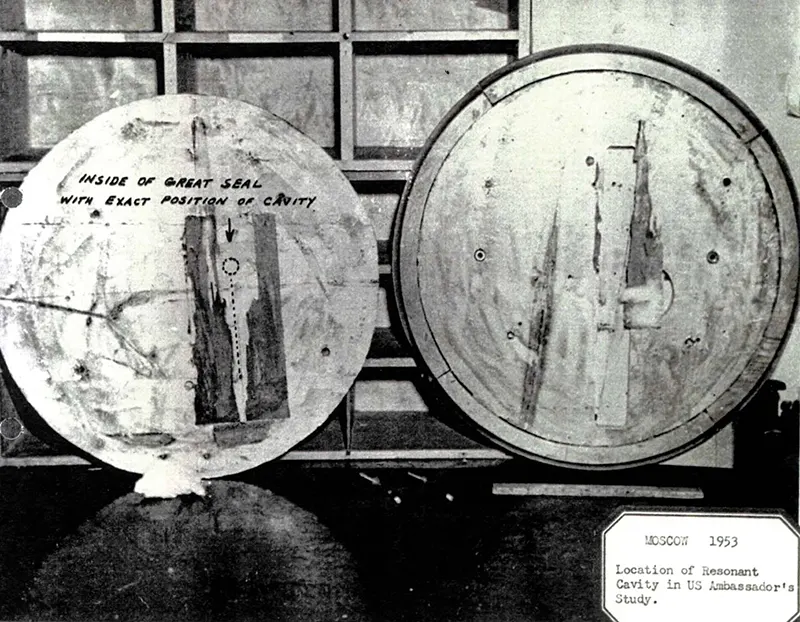

The bug itself consisted of a tiny capacitive membrane connected to a small antenna, hidden inside the wooden carving of the Great Seal. This device, a passive resonant cavity microphone, had no power supply or active electronic components, making it almost undetectable. It was designed to become active only when a radio signal of the correct frequency was sent to the device from an external transmitter. This signal would be modulated by the vibrations of the membrane (i.e., sound in the room), and the device would retransmit the modulated signal to a nearby receiver operated by Soviet intelligence.

The Exposure

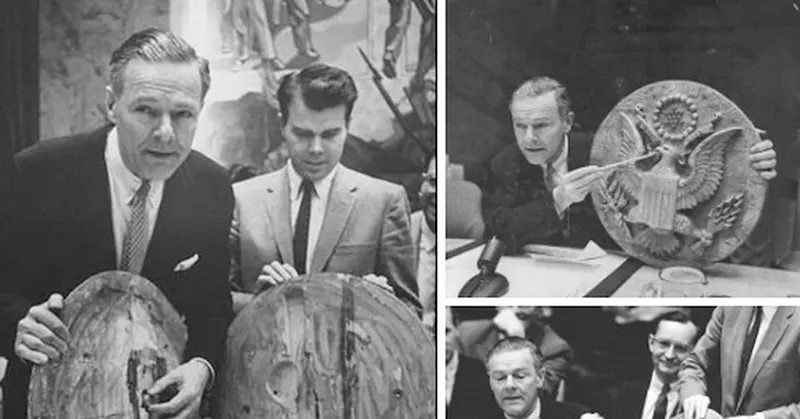

The “Thing,” as the bug was later called, went undetected for approximately seven years. It was only during a routine security sweep in 1952, ahead of a visit by the U.S. Secretary of State, that the device was discovered. The sweep involved a new procedure using signal generators and receivers that accidentally detected the resonant frequency of the bug.

The initial reaction was one of disbelief. Upon realizing the implications of this breach, shock set in among the American intelligence community. The bug’s discovery led to an immediate and thorough examination of all sensitive areas within U.S. diplomatic premises worldwide. This incident marked a significant shift in American counterintelligence procedures and policies.