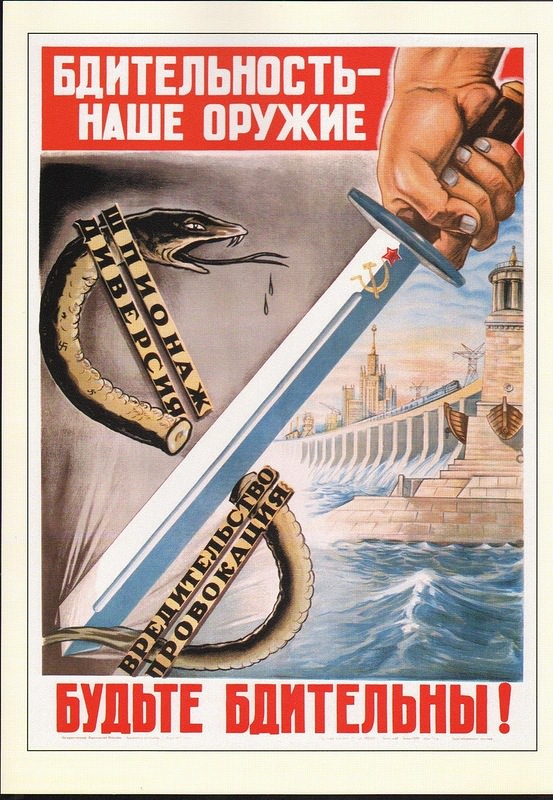

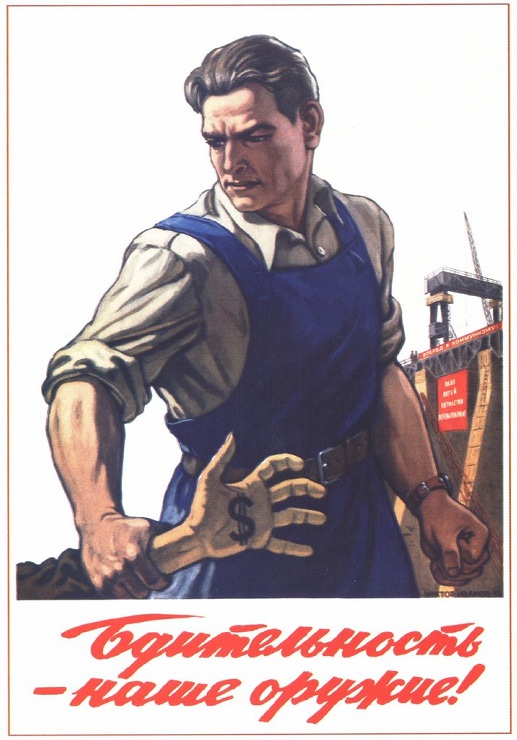

During the 1950s, the Cold War created an atmosphere of suspicion and tension between the Soviet Union and Western nations. This climate was reflected in everyday life through various forms of communication, including posters. A common sight across the USSR during this decade were bold anti-spy posters, designed as constant public service announcements warning citizens about the dangers of espionage and the vital importance of maintaining secrecy. While created with serious intent in a tense era, the direct messages and distinct visual style of these posters can appear striking, and perhaps even unintentionally humorous, to some modern viewers.

Although Soviet authorities had focused on combating perceived foreign spies intensely in earlier periods like the 1930s, the decade and a half immediately following World War II saw a true flourishing of the anti-spy poster as an art form. Historical context indicates that many of the most recognizable and now classic examples of this specific type of poster art were produced during the 1950s. These images became a part of the visual landscape for Soviet citizens.

A recurring and dominant theme in these posters was the danger posed by careless talk. Citizens were constantly reminded that unguarded conversations could have serious consequences. Slogans were often blunt and direct. For instance, a 1954 poster by artist V. Koretsky proclaimed, “Shout[ing] – helping the enemy,” warning against loud boasting or discussing potentially sensitive information openly. Similarly, a poster from the same year by K. Ivanov and V. Briskin declared, “Gossip, gossip – [plays into] the hands of the enemy.” The clear implication was that even seemingly harmless chatter could provide useful pieces of information to adversaries. This message was reinforced by posters like one from 1958 by J. Miracles, which simply commanded, “Do not talk!”

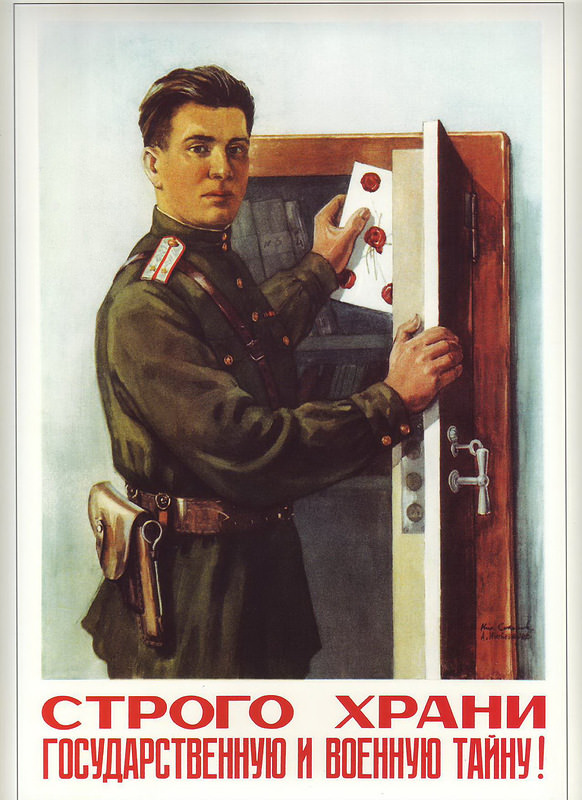

Protecting official secrets was presented as a critical civic duty. Several posters carried variations of the stark reminder: “Strictly keep military and state secrets,” such as examples produced in 1952 (by A. Intezarov and N. Sokolov) and 1958. The perceived need for secrecy extended even into personal life. A 1954 poster by K. Ivanov specifically cautioned people writing letters home, advising them to “look, you do not accidentally become loose [with] military secrets.” The underlying message was that any piece of information, no matter how trivial it might seem, could potentially be exploited by enemies.