In the 19th century, Paris was famed as much for its revolts as for its noxious odours. The streets overflowed with garbage and horse dung, and anyone caught in the open relieved themselves in the open.

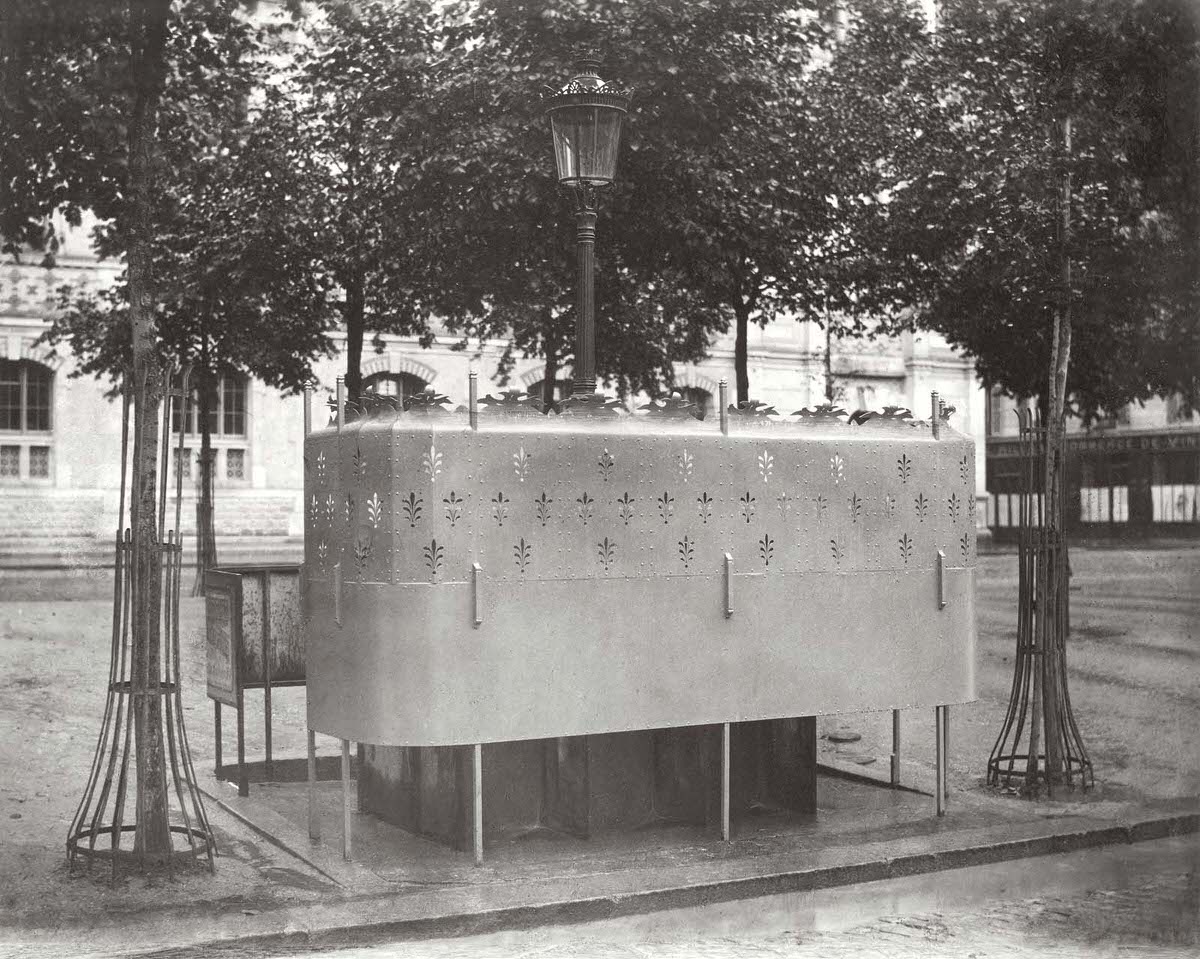

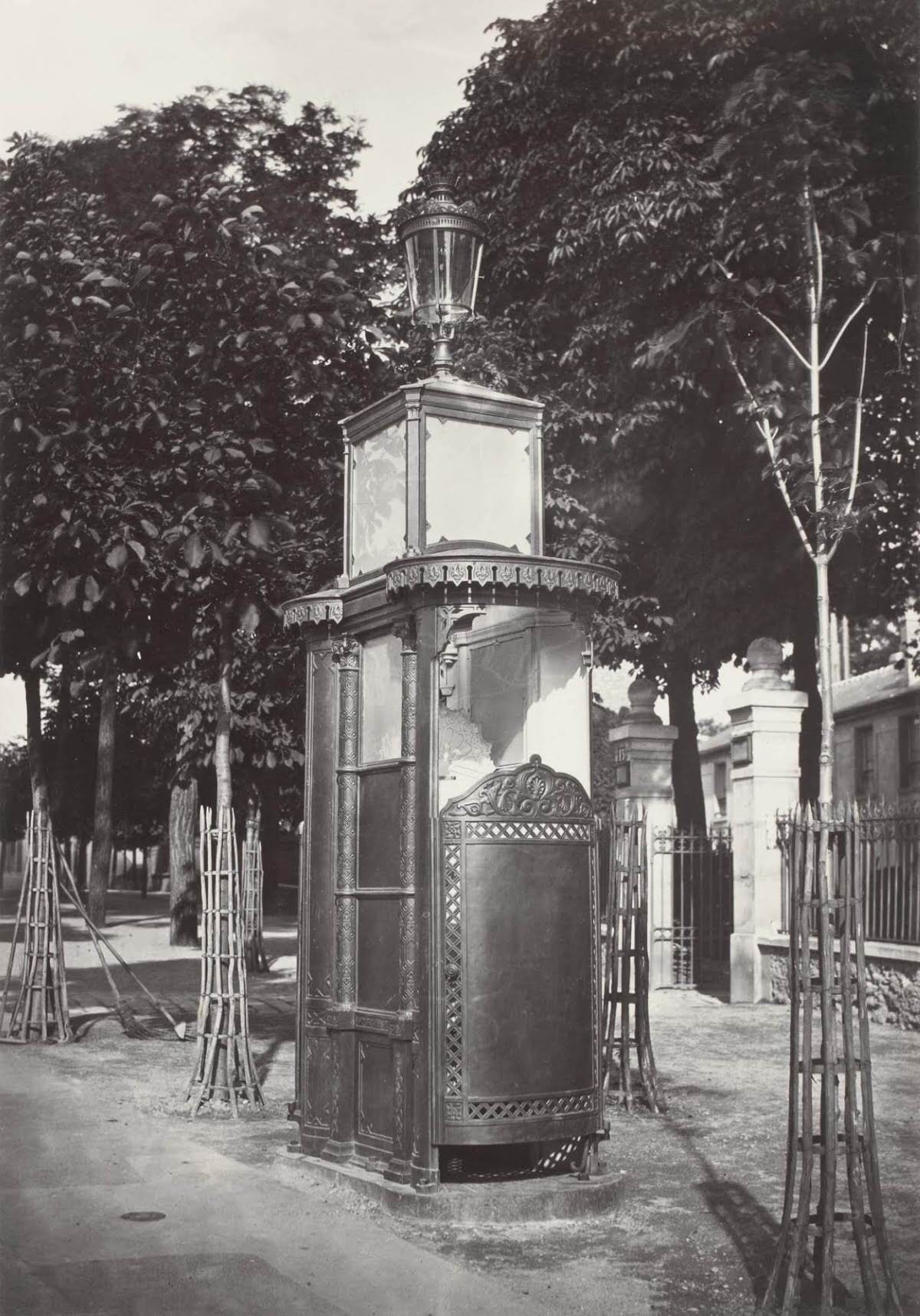

During the 1850s, public urinals – phallic-looking structures with plumbing – were constructed, which allowed Paris’s male population to urinate with relative dignity. They were known as ‘colonies Rambuteau’ (‘Rambuteau columns’) because of their simple cylindrical shape, built of masonry, open on one side and ornately decorated on the other. As the name Vespasianians implies, Rambuteau proposed the name to prevent his name from becoming associated with urinals, in honor of the Roman emperor Titus Flavius Vespasianus. He taxed public toilets for collecting urine for tanning. Street urinals were called pissoirs in the French-speaking world, rather than pissoirs, a French-sounding word used in other countries.

Despite the lack of full privacy, the male’s torso remained covered, which prevented other Parisians from snooping on one’s intimate parts. When pissoirs became popular, they helped clean up the mess of stale urine caused on the streets. Baron Haussmann’s remodelling of the city later led to the introduction of cast iron urinals. Various designs were produced in subsequent decades, usually covering the central portion of the man’s body from public view and leaving his feet and head exposed. Screens were also added to Rambuteau columns. Although the idea of constructing conveniences for women was briefly considered, it was decided that they would take up too much space on public thoroughfares.

During the 1930s, there were 1,230 pissoirs in Paris, but by 1966, that number had decreased to 329. Pissoirs during World War II were places where French Resistance members could meet for a private conversation or leave a message without the Germans knowing about it. Since 1980 they were gradually replaced with new technology, a self-cleaning, enclosed, unisex unit called the Sanisette. There was only one remaining pissoir on the Boulevard Arago by 2006.

Charles Marville, one of the most renowned and gifted photographers of the nineteenth century, took the photos. Paris commissioned him to document the changing city, especially the landmarks built by Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann.

It’s supper time!

I bring the wand!

It was better before

For the time being, public toilets are a considerable deficiency in present-day Paris.