Wakefield Asylum was established in 1818, initially providing for 150 patients. Samuel Tuke, a pioneer in mental health care of his time, helped shape the design of the institution. Tuke’s principles were driven by a deep-rooted belief in humane treatment and progressive care, elements that were revolutionary in a time when society’s approach to mental illness was often one of fear and misunderstanding.

Dr. William Charles Ellis, the asylum’s first medical director, set the tone for the place’s dedicated care, serving until 1831. However, as the years passed, the institution saw its walls expand. By the mid-1860s, the asylum was home to over a thousand souls, each with their unique stories and struggles.

A New Chapter with Crichton-Browne

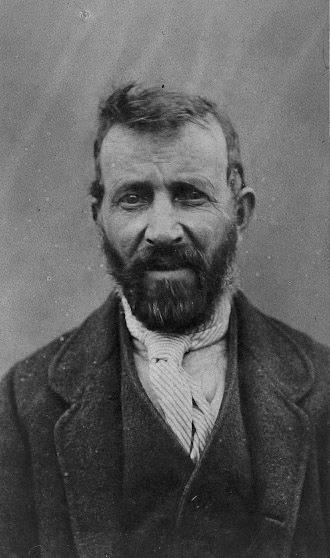

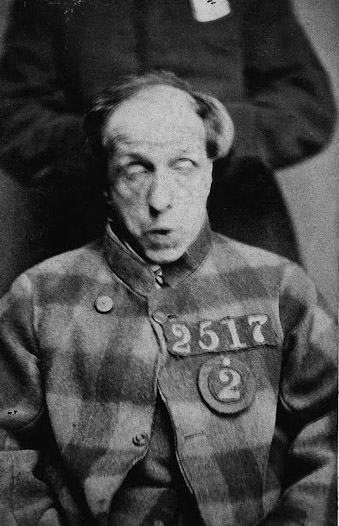

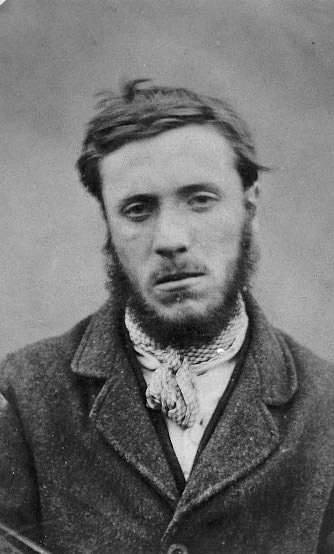

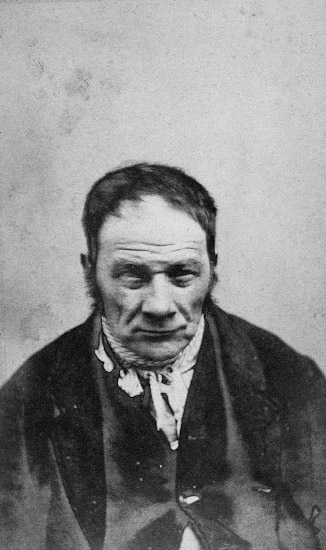

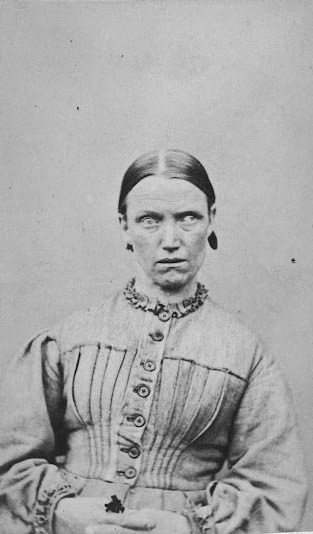

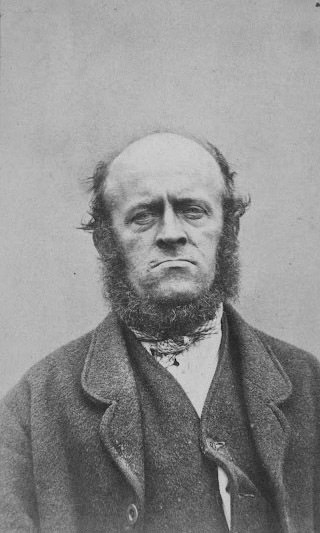

The arrival of James Crichton-Browne as superintendent in 1866 ushered in a new era. Crichton-Browne, a renowned Victorian psychiatrist, was known for his progressive approach towards psychiatry and introduced many reforms that put patients’ welfare at the heart of the asylum’s operations.

Crichton-Browne’s tenure was marked by an emphasis on individual care and therapy. He made an effort to understand patients’ unique struggles, a far cry from the often inhumane and impersonal methods used in many such institutions of the time.

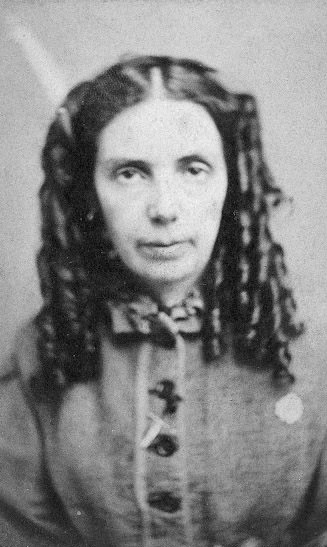

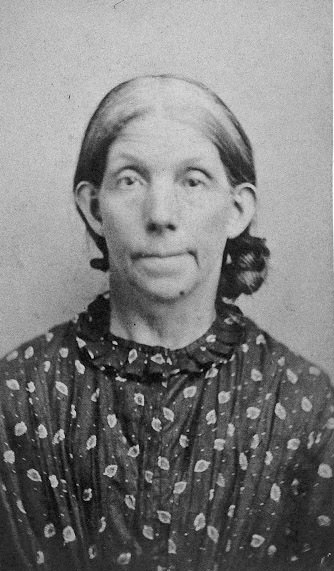

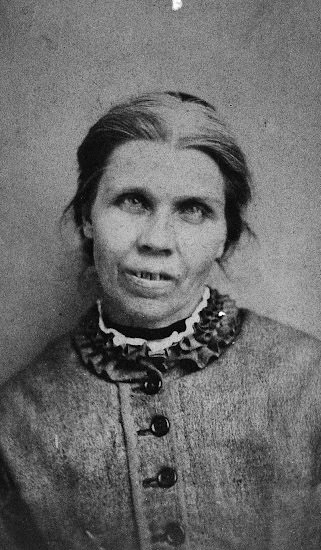

Life Inside the Asylum

Let’s peel back the layers of history to understand life inside Wakefield Asylum in the 1860s. Upon entry, each patient was assessed and received a personalized treatment plan, marking an early adoption of individualized care in psychiatric treatment. The days were structured, comprising therapies, work tasks, and recreational activities. This provided patients with a sense of purpose and helped establish routine and stability, critical components of the therapeutic environment.

The asylum was a bustling community. Patients worked in the institution’s various departments, including the kitchen, the gardens, or the laundry. This not only gave them purpose but also helped cultivate skills that would be valuable upon their reintegration into society.

Leisure was not forgotten. Patients engaged in games, music, and arts to foster a sense of camaraderie and to provide outlets for self-expression. These elements of life were considered crucial to their recovery process and overall wellbeing.