Two nuclear tests were conducted in the mid-1960s at Tatum Salt Dome near Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Nuclear test yields were disguised during the Salmon test on October 22, 1964, and the Sterling test on December 3, 1966, to determine how well such blasts could be detected.

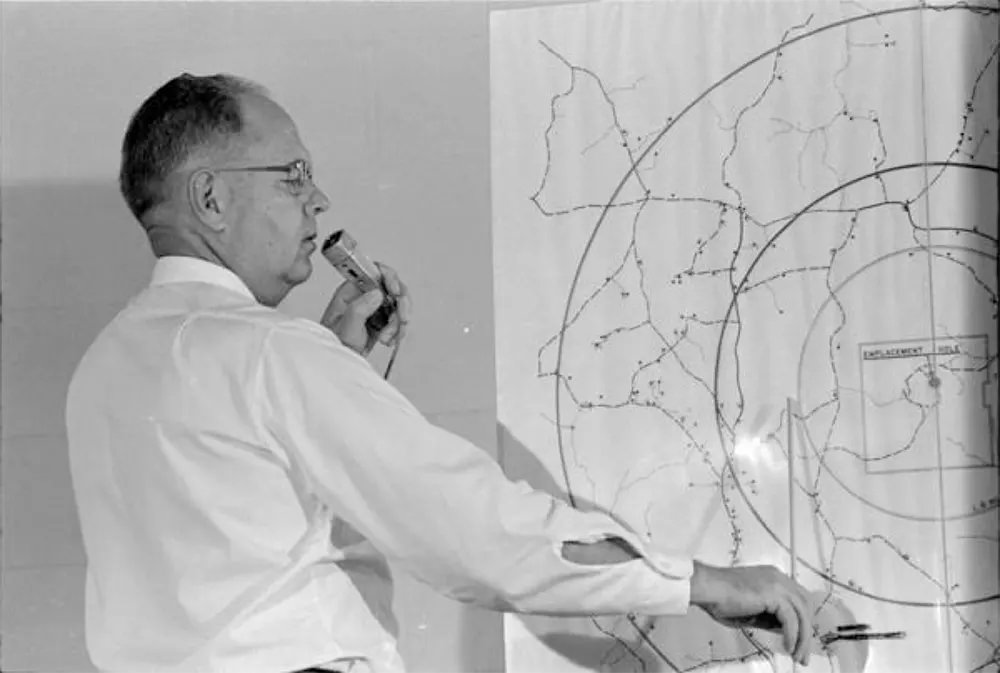

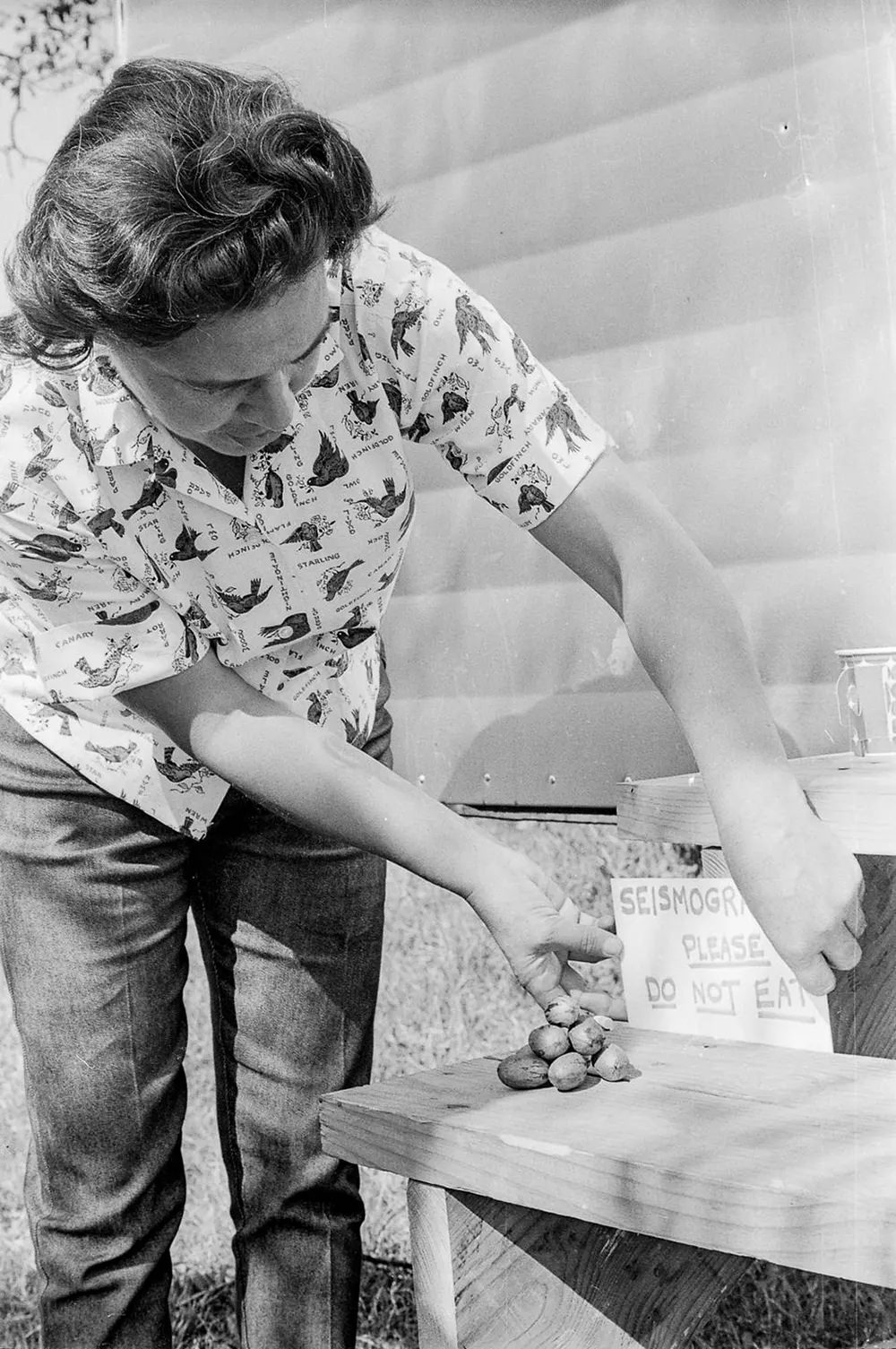

It took nine years of negotiations for the United States, Soviet Union, and other countries to sign the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (LTBT), which forbade nuclear weapons testing explosions, as well as any other nuclear explosions, “in the atmosphere, outside of it, including outer space, or underwater, including waters or high seas.” Despite disagreements and uncertainty, the Treaty did not address underground testing. Seismographs are generally capable of detecting underground nuclear tests. Project Dribble was designed to find out if cheating nations might conceal their underground tests by using the two Mississippi detonations, which included the investigation of confidential testing and detection. Two detonations were planned. The first blast would occur 2,700 feet below the surface of solid salt, codenamed Project Salmon. The second detonation, Project Sterling, would use a smaller bomb to fill the cavity left behind by the first explosion. The second detonation shockwaves would be muffled by the cavity, effectively preventing seismograph detection of this second explosion.

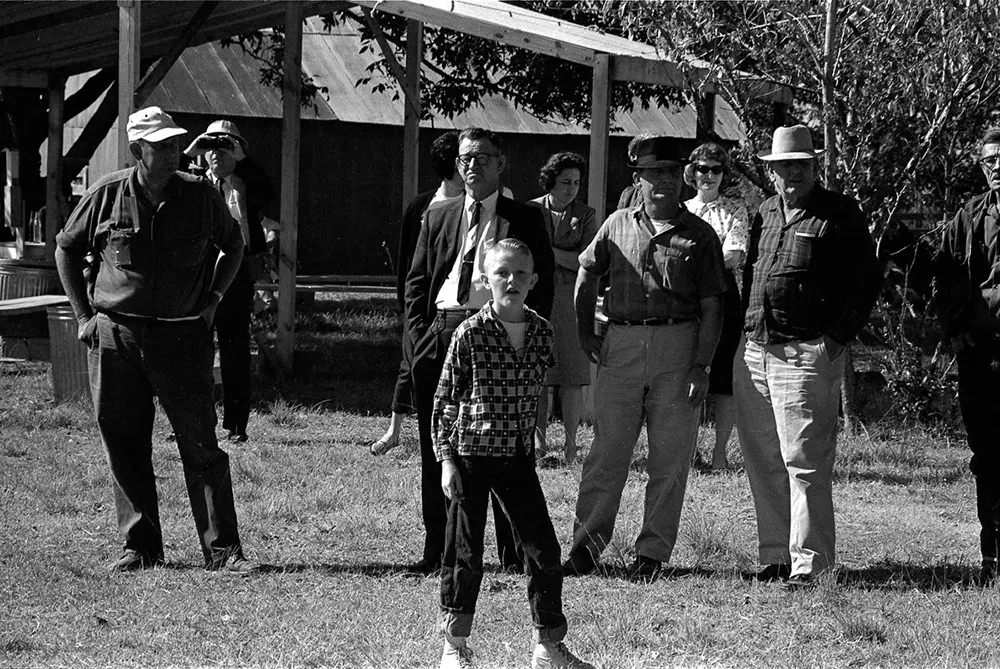

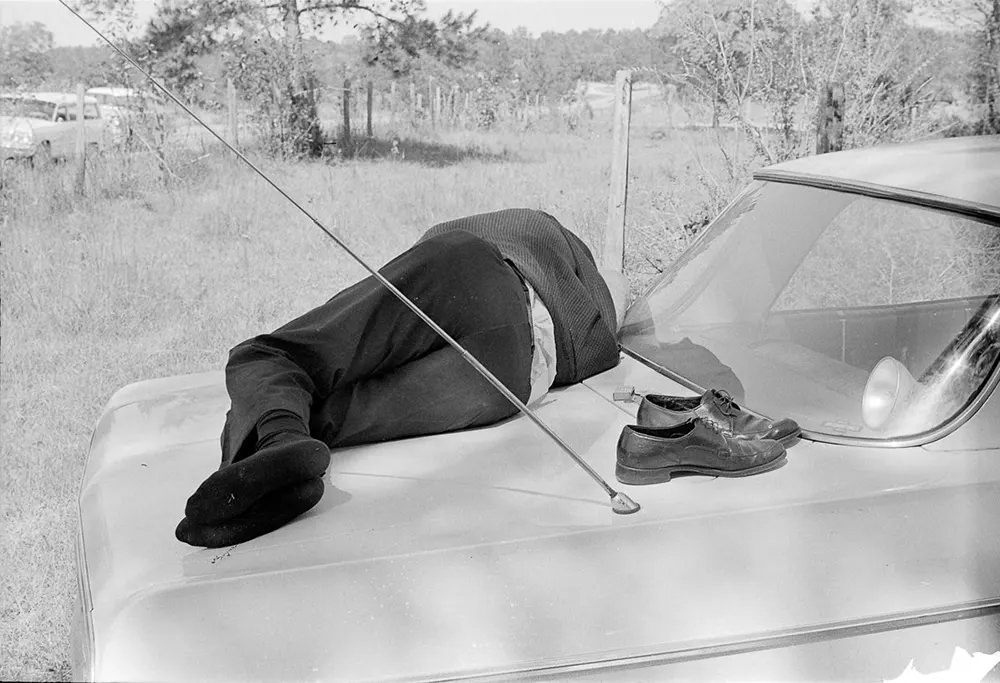

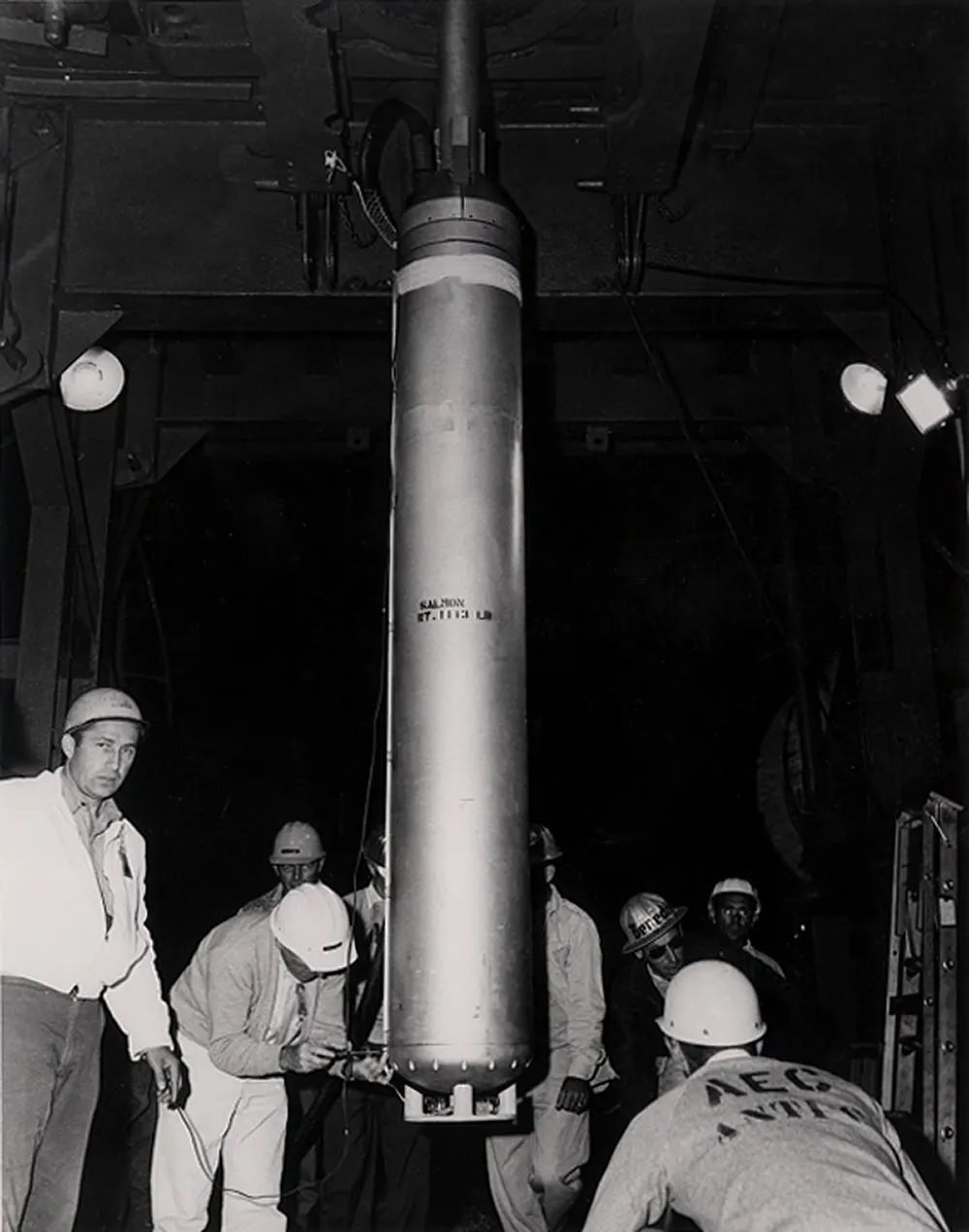

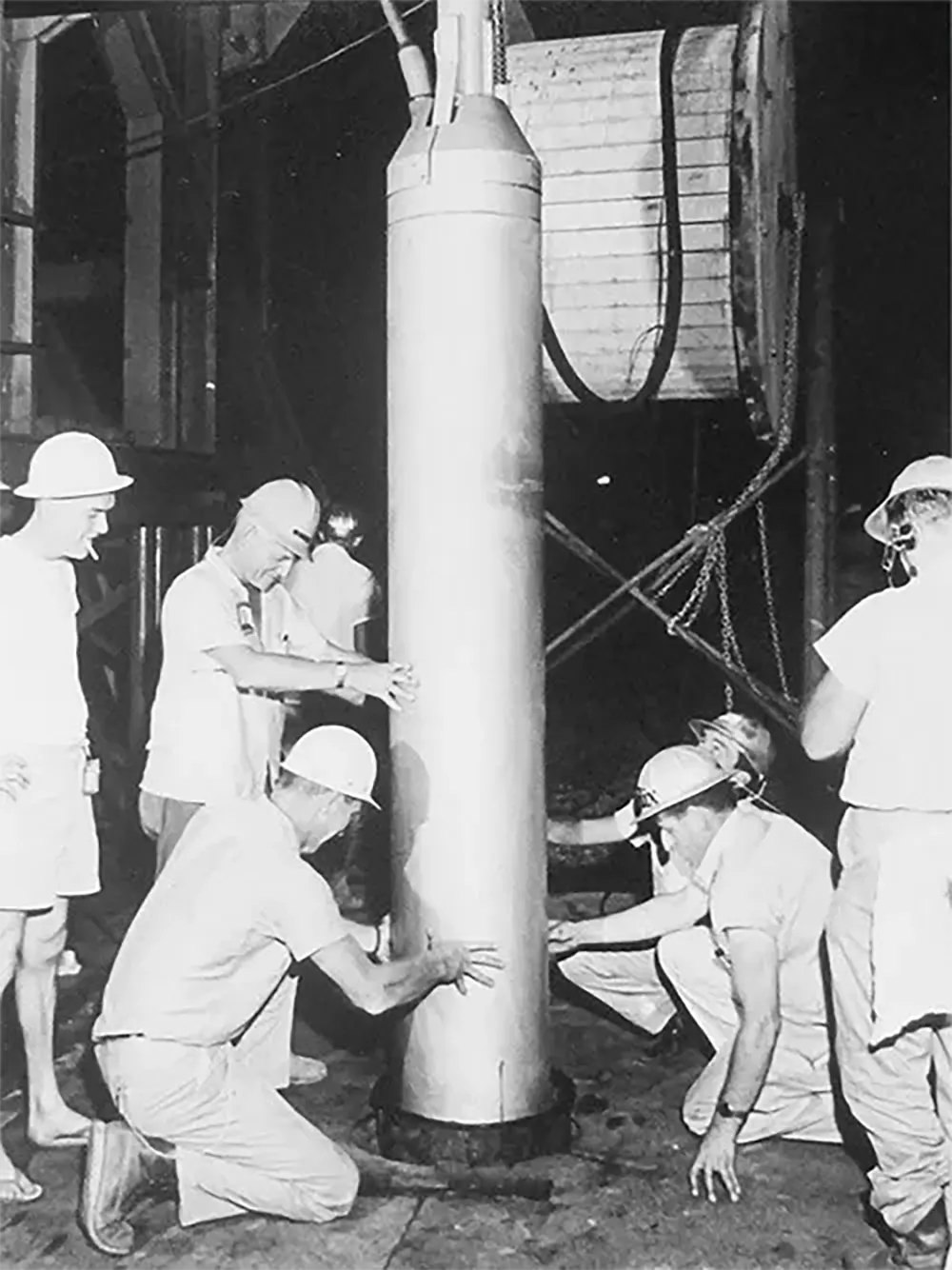

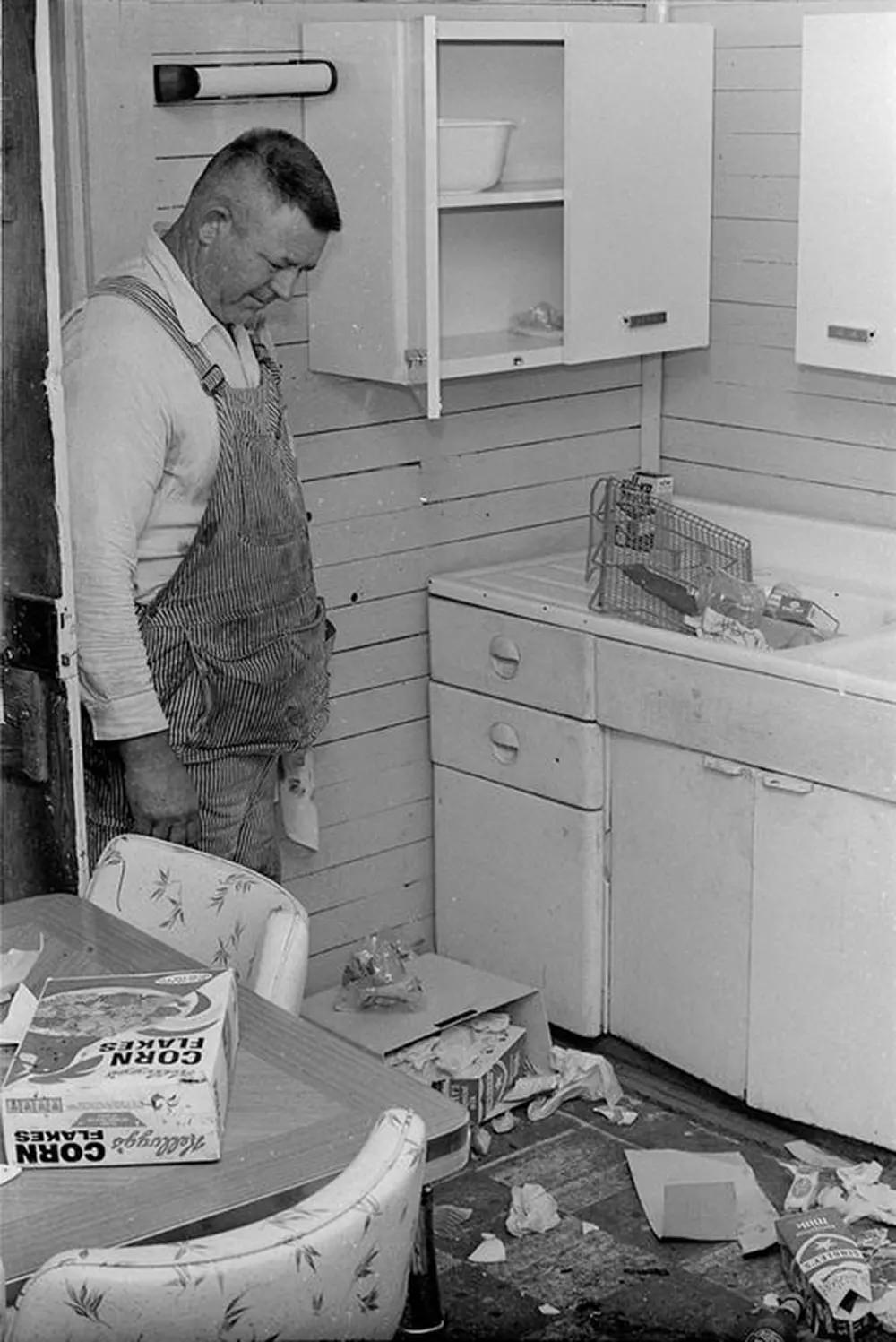

The Atomic Energy Commission began preparing the Tatum Salt Dome site for Project Salmon in 1964. More than 100 residents of Lamar County worked on the project site, primarily driving trucks and heavy equipment or providing food for the workers. A nuclear test was scheduled for September 22, 1964, but the wind direction wasn’t right until October 22. A total of 400 residents were evacuated on that date and paid $10 per adult and $5 per child for their inconvenience. Most residents later reported that they were shocked by the explosion much more than they had been led to believe. Hattiesburg American editor experienced nearly three minutes of shaking despite living about thirty miles away. Over 400 nearby residents had filed damage claims with the government seven days after the blast, reporting that their homes or water wells had been damaged. Burge, who lived about two miles from the explosion site, returned home to discover considerable damage to his three-room house. The fireplace and chimney were severely damaged, and bricks littered the living room. His kitchen floor was littered with broken dishes and jars, his refrigerator shelves fell, and several glasses were broken. His electric stove was covered with ash and pieces of concrete. There had been a burst of pipes under his kitchen sink, which resulted in flooding throughout the house.

Residents of the affected areas began receiving reimbursements from the United States government within days of the damage being done. According to government scientists, Project Salmon delivered the same force as 5,000 tons of TNT after seismic analysis. Project Salmon’s blast was about one-third as powerful as Hiroshima’s bomb in 1945. As predicted, the bomb created a 110-foot-diameter spherical cavity in the salt. Project Sterling’s blast on December 3, 1966, was substantially weaker than its blast two years earlier. While Project Salmon’s bomb had the force of 5,000 tons of TNT, Project Sterling’s bomb had the force of 350 tons. Two miles away from the blast, observers barely felt a bump. Project Sterling was deemed a success, just like Project Salmon. According to U.S. government officials, Mississippi’s two nuclear blasts, as part of Project Dribble, proved that the seismic effect of a nuclear blast could be greatly reduced if it were set off in a cave. In addition, it taught atomic scientists how to detect and measure such hidden explosions. Hence, a nation might be able to cheat on a future nuclear test ban by concealing a nuclear test.

The location of the nuclear bomb tests is marked by a granite monument surrounded by test wells. Radiation from Projects Dribble and Sterling began to cause cancer-related deaths in Hattiesburg in the 1990s. Former workers and contractors who worked on these projects and “workers who lived in Mississippi but did not necessarily work” on them received $16.8 million from the federal government in 2015.