In the early 1980s, the tech world was buzzing with innovation. One of the most intriguing inventions of that time was the MetaWriter software vending machine. Created by Nolan Bushnell, the founder of Atari, this machine promised to change how people accessed software. Instead of going to a store and buying physical copies of software, users could download programs directly into reusable cartridges. This concept was groundbreaking and would pave the way for future software distribution methods.

The Vision Behind the MetaWriter

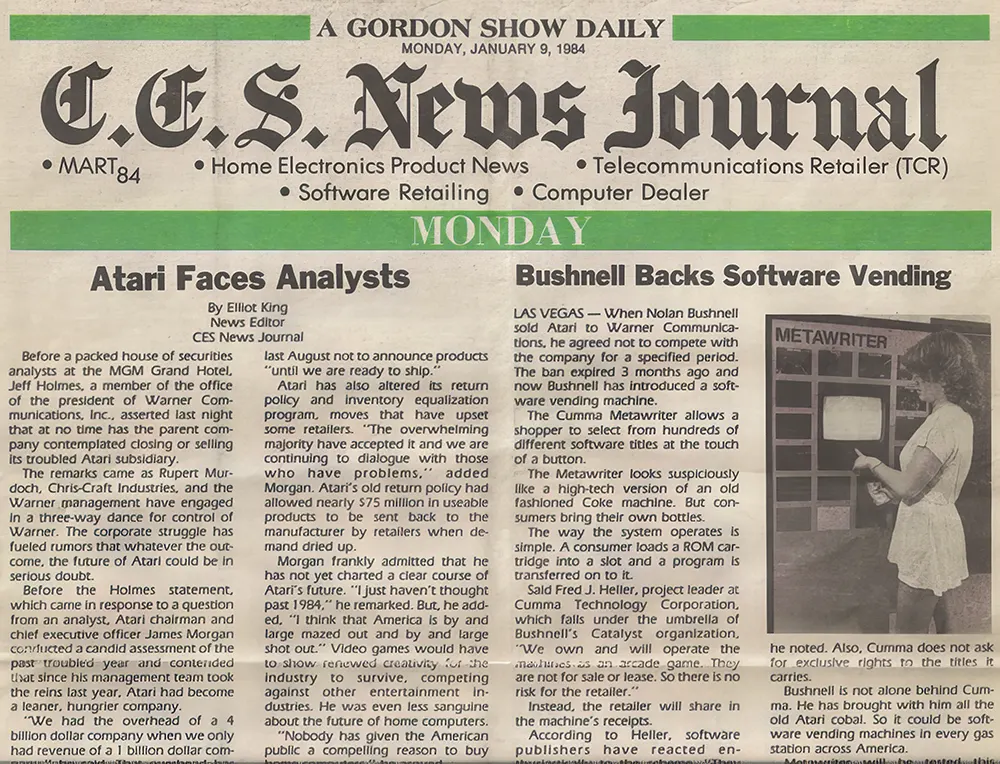

Nolan Bushnell is best known for founding Atari, which revolutionized the video game industry with games like Pong. However, after selling Atari to Warner Communications in 1976, Bushnell faced restrictions that prevented him from launching competing products. After the expiration of these restrictions, he launched the Cumma MetaWriter in 1983.

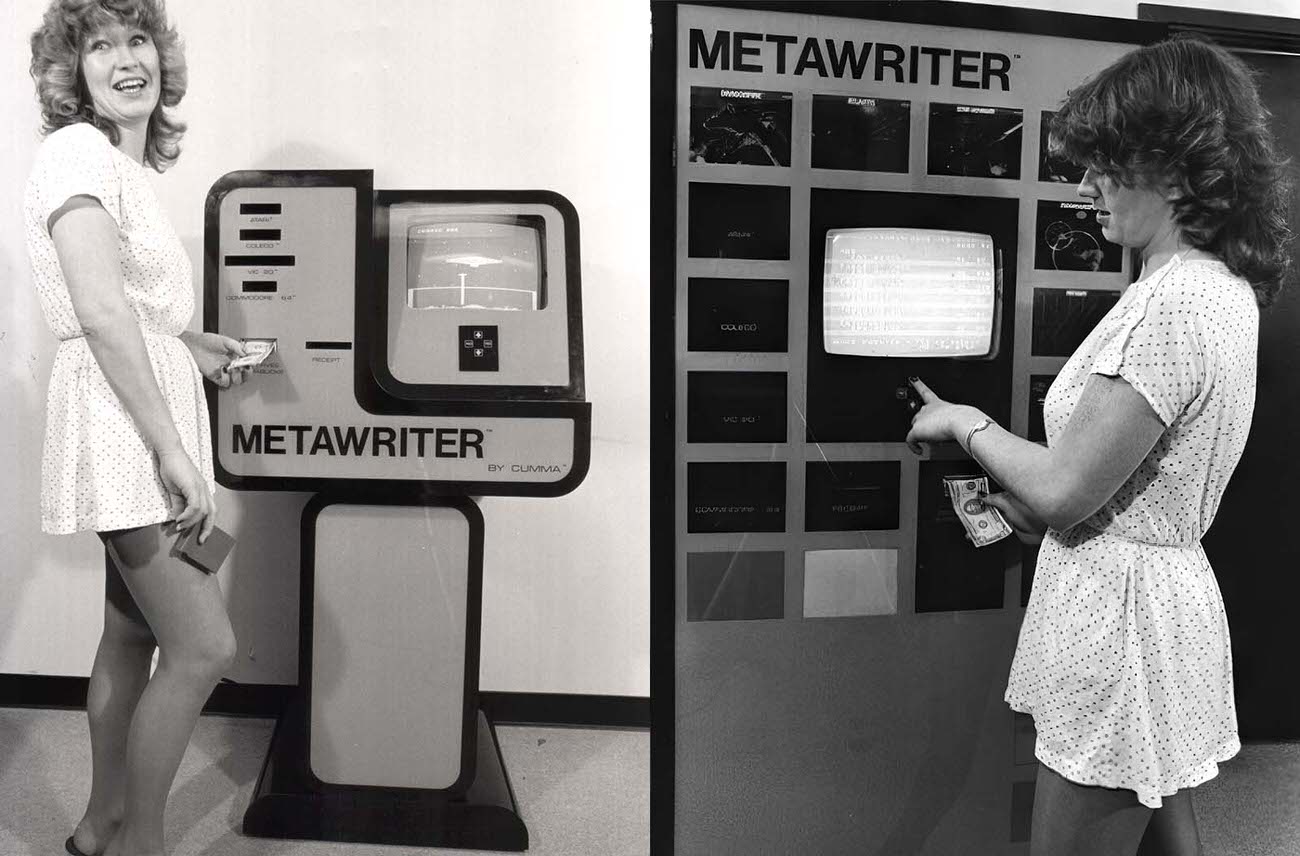

Bushnell envisioned the MetaWriter as a solution to the growing demand for software in an increasingly digital world. The machine was designed to be as easy to use as a classic vending machine. Instead of purchasing a physical disk or cartridge, users could select from hundreds of software titles at the push of a button. This convenience was particularly appealing in a time when personal computers were becoming more common in homes.

How the MetaWriter Functioned

The MetaWriter operated in a straightforward manner. Users would bring their own ROM cartridges to the machine. After inserting their cartridges into the designated slot, they could browse through the available software titles displayed on the machine’s screen. The process was similar to selecting a soda from a vending machine.

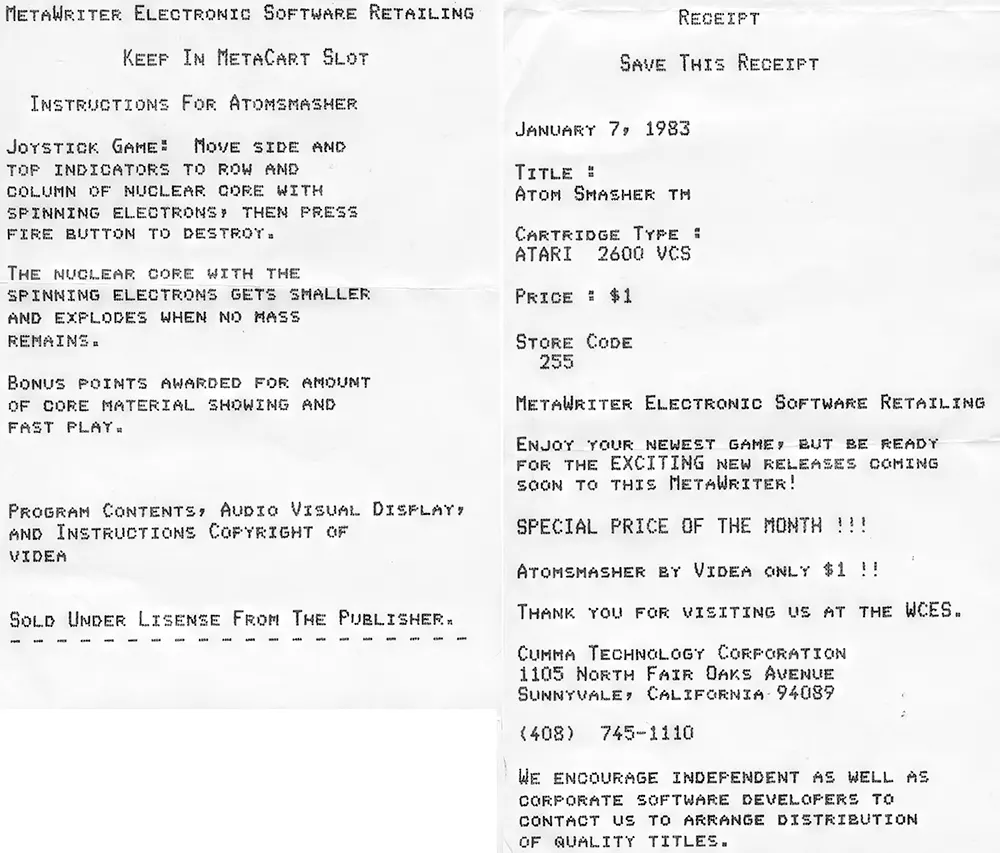

Once a user selected a program, they would insert money into the machine. The MetaWriter then copied the chosen software onto the user’s cartridge. This transaction took place quickly, often in less than a second. After the download, the user would receive a receipt, instructions for the software, and promotional literature about upcoming programs.

This self-service model allowed customers to access software without needing assistance from store clerks. The machines required only a standard electrical outlet, making them easy to install in various locations like convenience stores, drugstores, and department stores.

The Software and Cartridges

The MetaWriter used reusable RAM cartridges for storing software. These cartridges were powered by batteries, which had a lifespan of about five years. While the initial cartridges were temporary solutions, Bushnell’s company planned to introduce nonvolatile cartridges that would not require batteries.

The cost of software ranged from $7 to $9 per program. For many consumers, this was an attractive price point compared to traditional purchasing methods. The MetaWriter aimed to make software more accessible, especially to younger audiences such as teenagers who were interested in computer games.

Initial Reception and Market Testing

In 1984, InfoWorld magazine reported on the MetaWriter’s introduction at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas. The machine received a mixed response. While some software developers expressed outrage over the concept, claiming it would undermine the software industry, others saw potential in this new distribution method.

Cumma Corporation, the company behind the MetaWriter, planned to test the machines in about 50 locations in northern California. They hoped to have 1,000 units installed nationwide by the end of the year. The goal was to make the MetaWriter a common sight in retail locations, similar to soda vending machines.

The machine’s design came in two styles: a traditional boxy shape and a more futuristic model. This flexibility in design helped appeal to various retail environments. Store owners were also incentivized to install the machines for free, as they would receive a commission on sales.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite its innovative approach, the MetaWriter faced several challenges. The traditional software industry was resistant to the idea of vending machines for software. Many developers worried that this model would reduce the perceived value of their products. James Morgan, the president of Atari at the time, voiced concerns about losing control over product quality and presentation.

Critics argued that the vending machine model could lead to a decline in software quality. They feared that by making software easily accessible without proper vetting, consumers might end up with subpar products. This anxiety reflected broader concerns about how technology was changing the way people interacted with products.

While there were criticisms, the MetaWriter also offered several advantages. For consumers, the vending machine model eliminated the need for physical inventory. This meant that software publishers could save money on manufacturing and distribution. Instead of producing large quantities of software that might not sell, they could distribute programs directly from the machine.

Bushnell and his team believed that the MetaWriter could lead to lower software prices for consumers. By reducing overhead costs, they hoped to pass on savings to buyers. This could mean that people would pay less for software, making it more accessible to a broader audience.