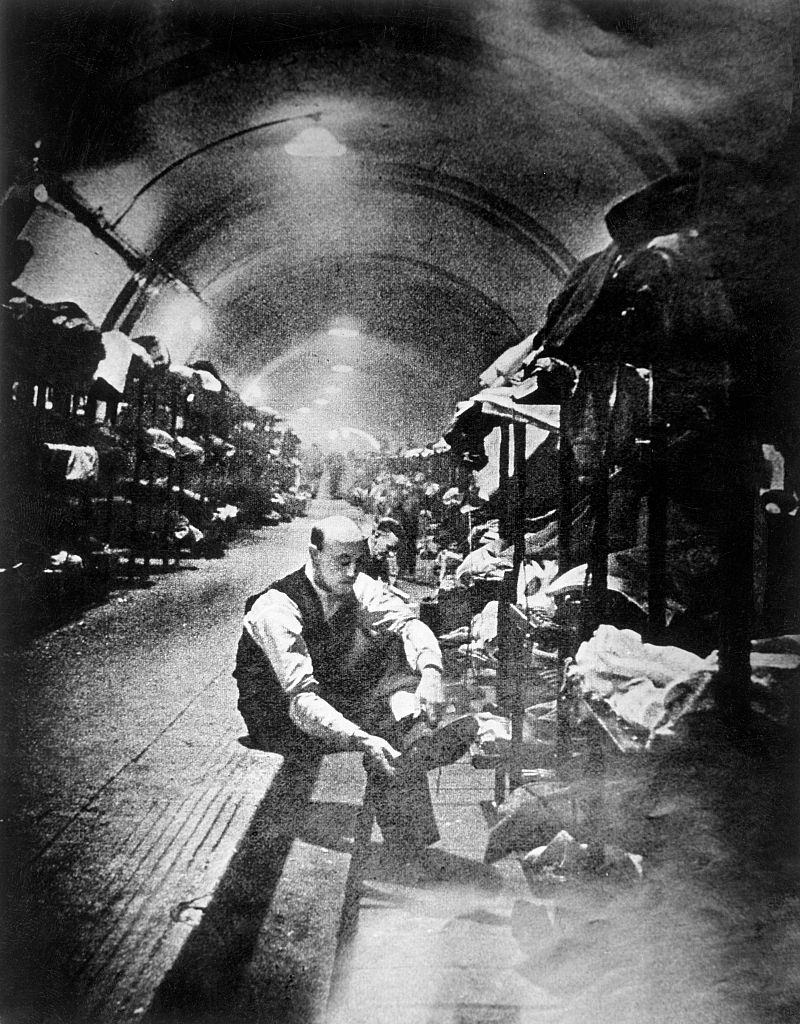

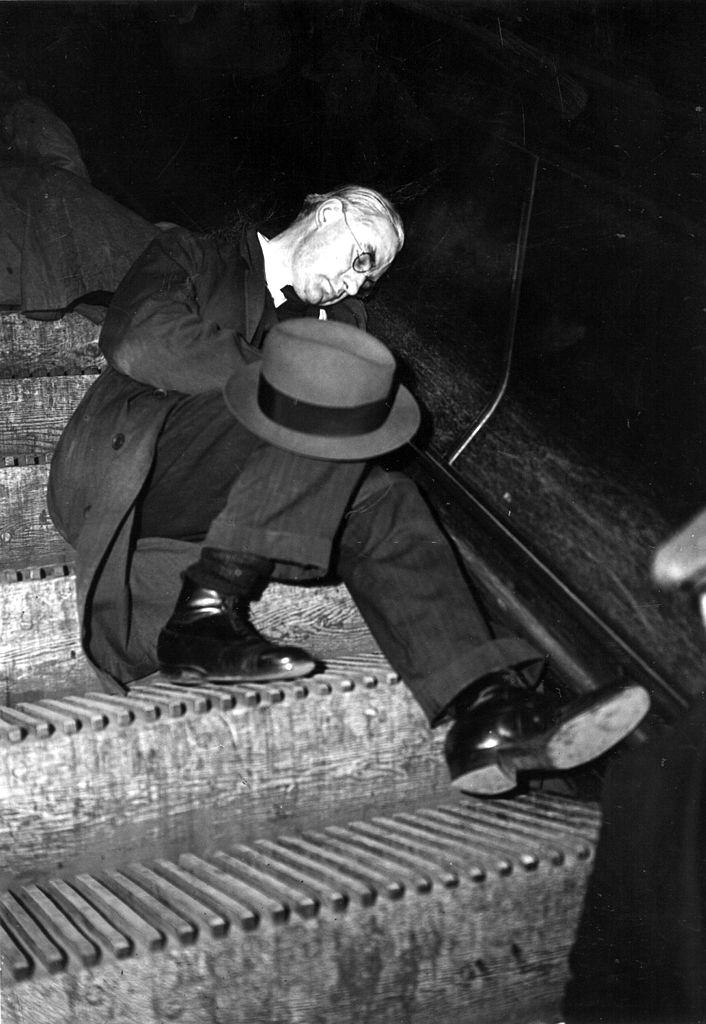

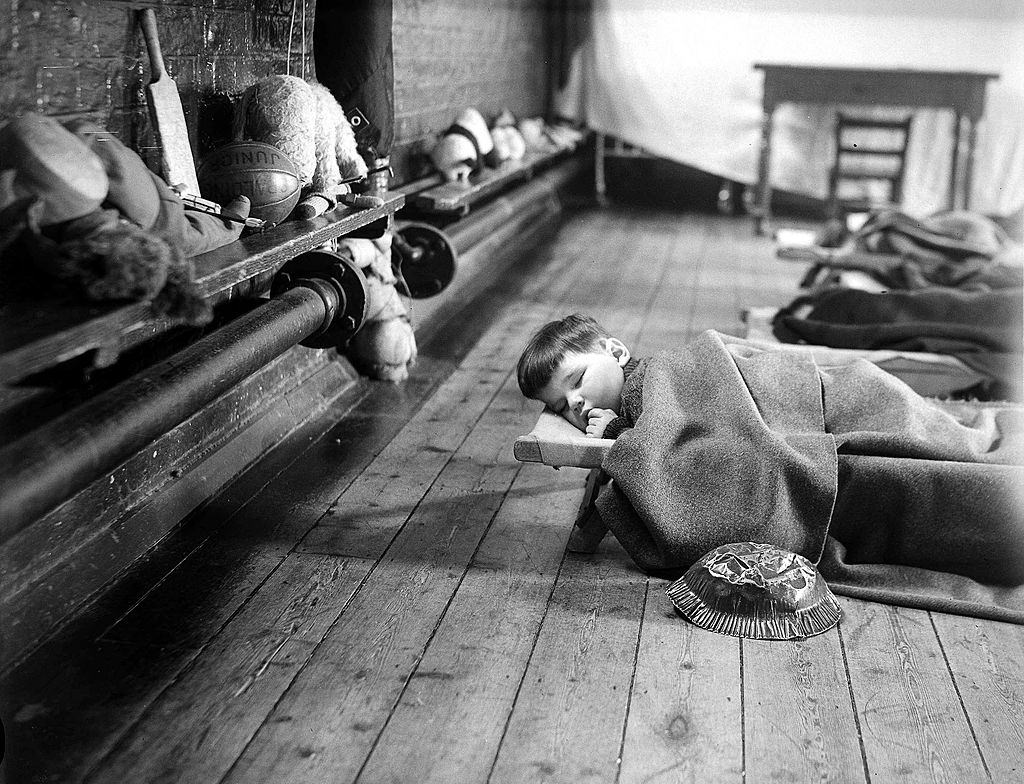

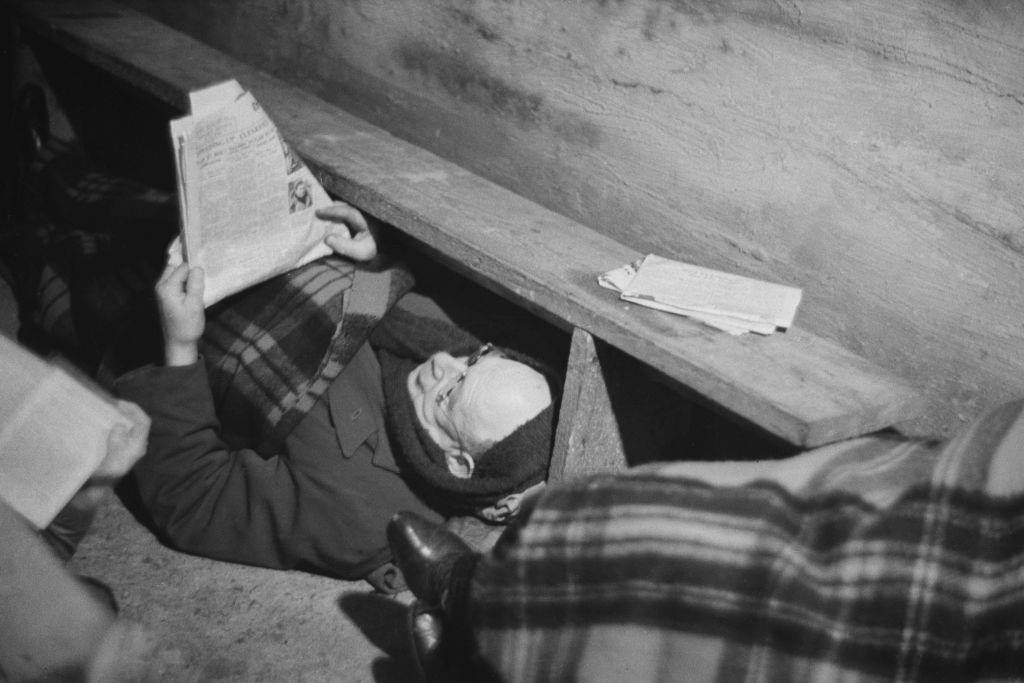

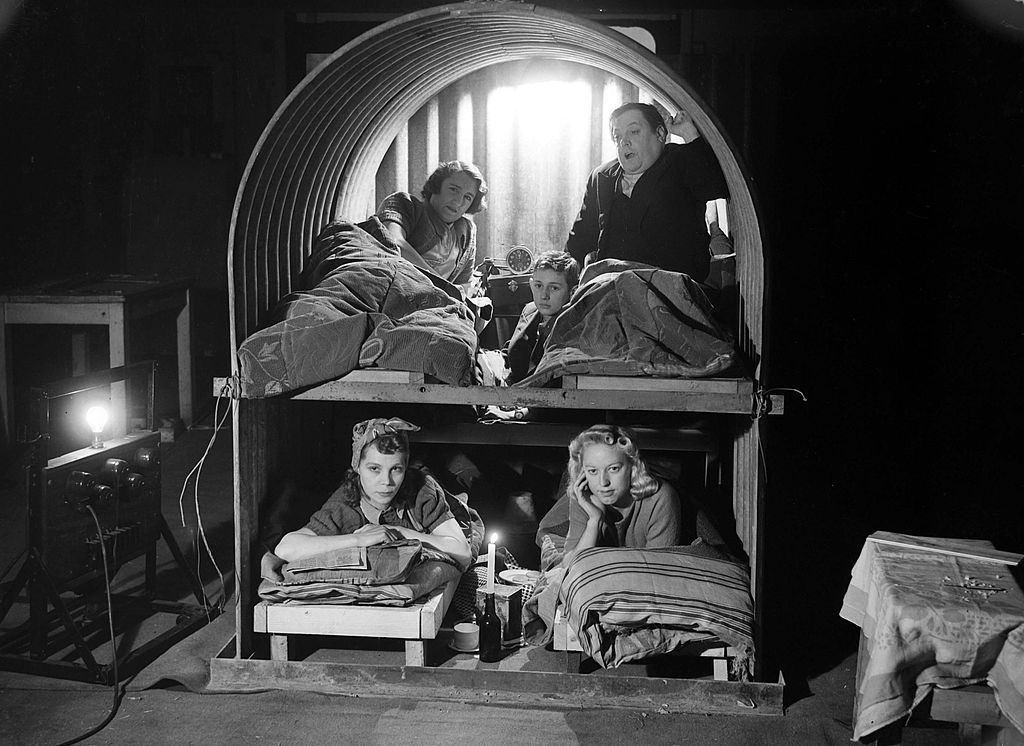

From September of 1940 through May of 1941, the Germans conducted a strategic bombing campaign against populated areas, factories, and dockyards in London and other cities in England, known as the Blitz. Many Londoners of all classes sought shelter on Underground platforms when German bombers rained down destruction above ground during the Second World War. The Luftwaffe bombing killed more than 40,000 civilians, almost half of them in the capital, where more than a million houses were destroyed. The London Underground stations were the most important communal shelters. Even though many civilians used these stations as shelters during the First World War, the government barred their use as shelters in 1939 to avoid interfering with commuter and troop travel and the fear that occupants might refuse to leave and prolong the war.

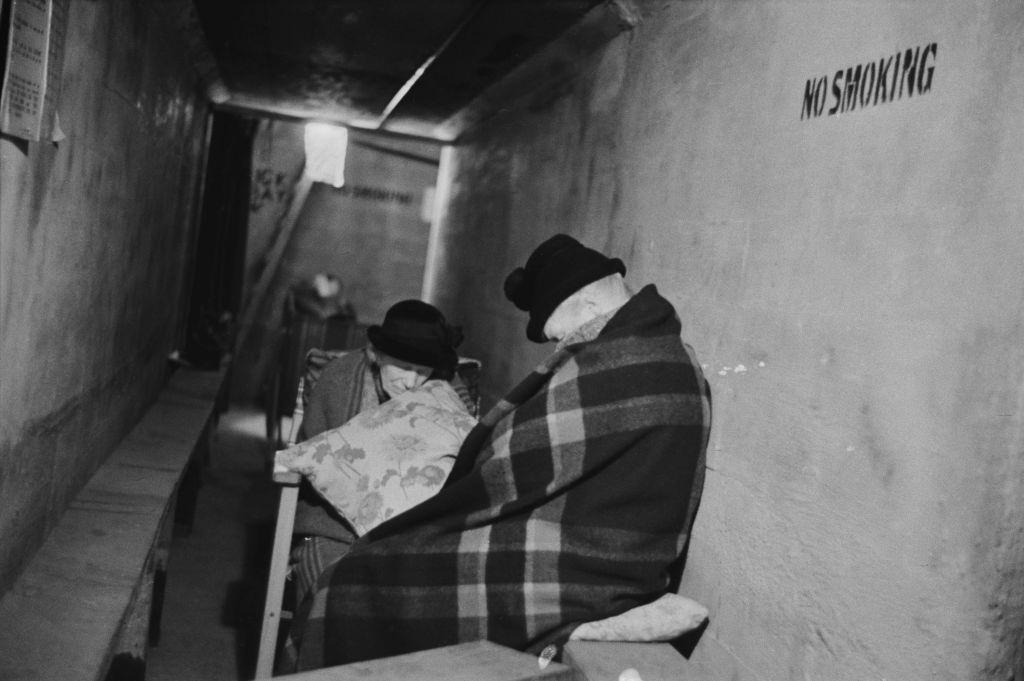

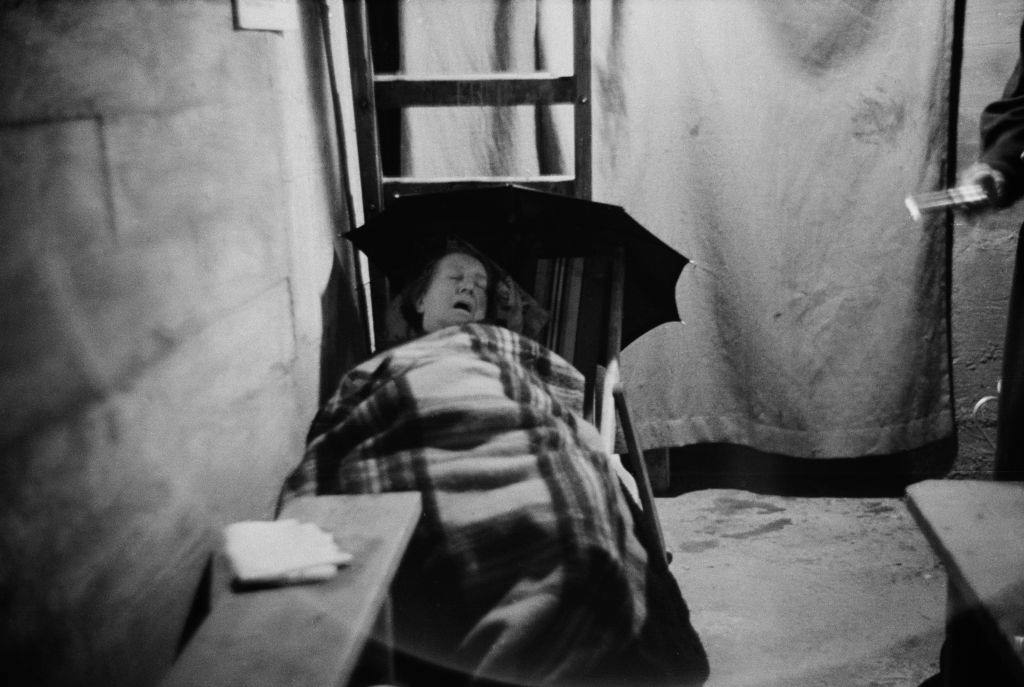

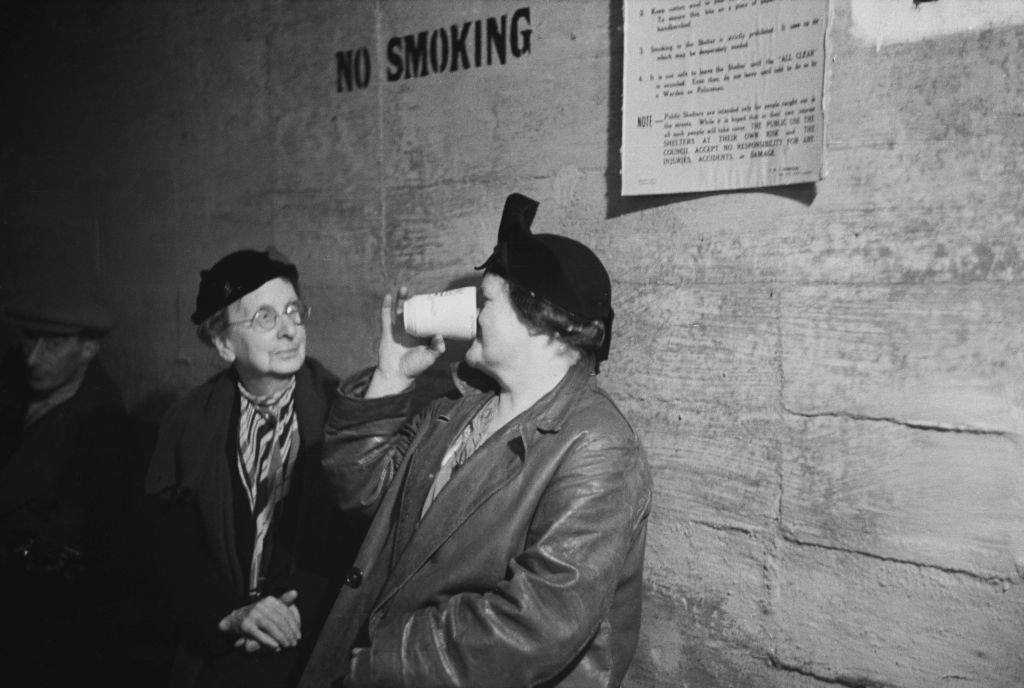

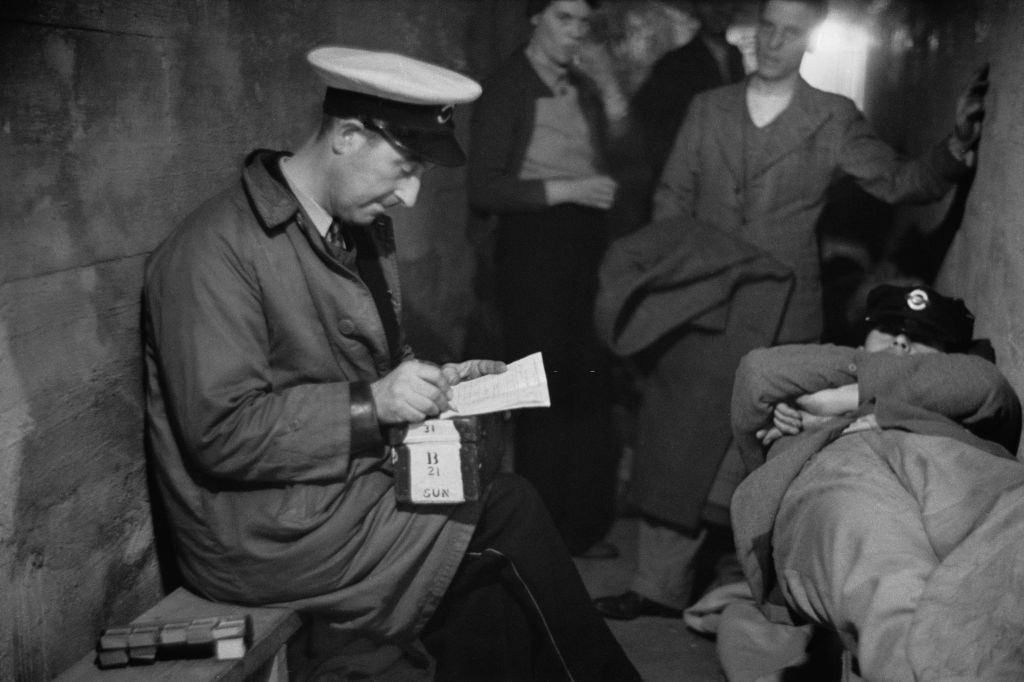

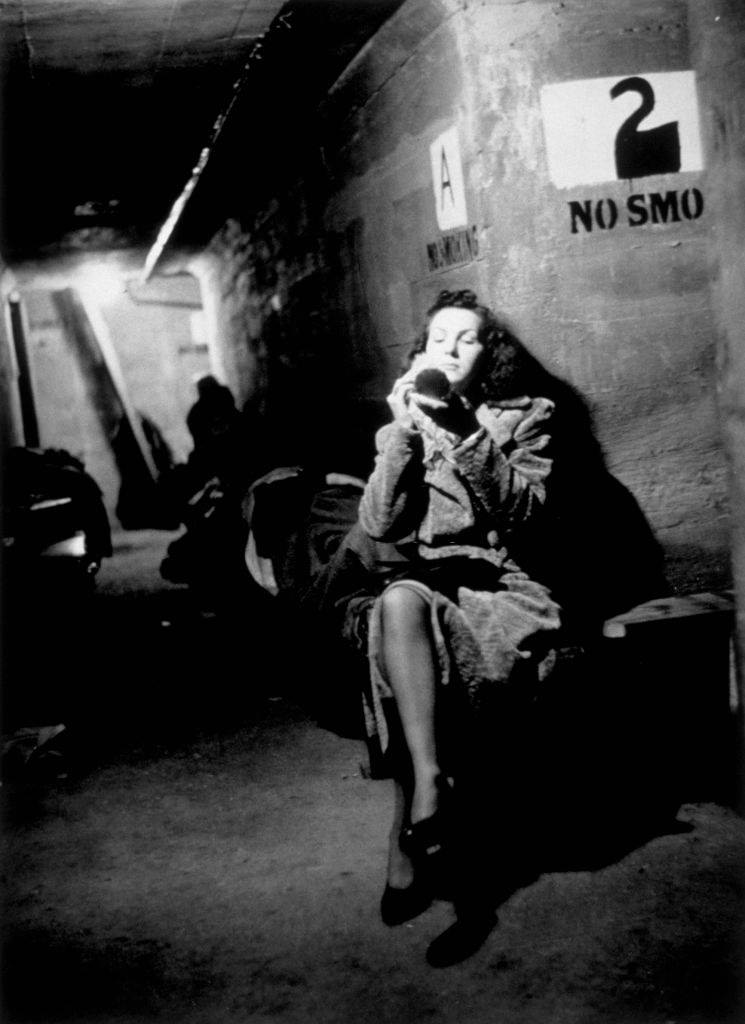

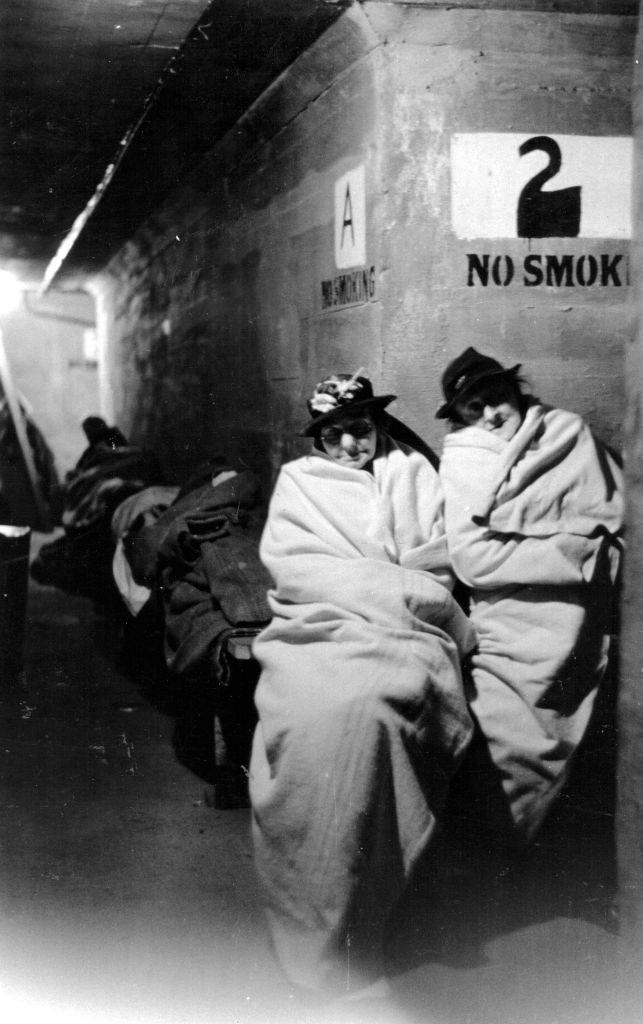

During raids, station entrances were locked, but by the second week of heavy bombing, the government relented and ordered them to be opened. The stations were open to the public until 4:00 p.m. when people queued in orderly lines. Around 150,000 people slept in the Underground each night in mid-September 1940, although by winter and spring, the numbers had declined to 100,000 or less. The deepest stations had muffled battle noises and were easier to sleep in, but many people died from direct hits on the stations. During a crowd surge at Bethnal Green tube station in March 1943, 173 men, women, and children were killed after a woman fell down the steps. One hundred sixty civilians were killed in a single direct hit on a shelter in Stoke Newington in October 1940.

177,000 people were using the Underground as shelter on 27 September 1940, and a census conducted in London in November 1940 found that 4% of residents used the Tube and other large shelters, 9% used public surface shelters, and 27% used private homes, indicating that the remaining 60% remained at home. By October 1940, the government had built new deep shelters for 80,000 people within the Underground, but the period of heaviest bombing had passed before they had been completed.

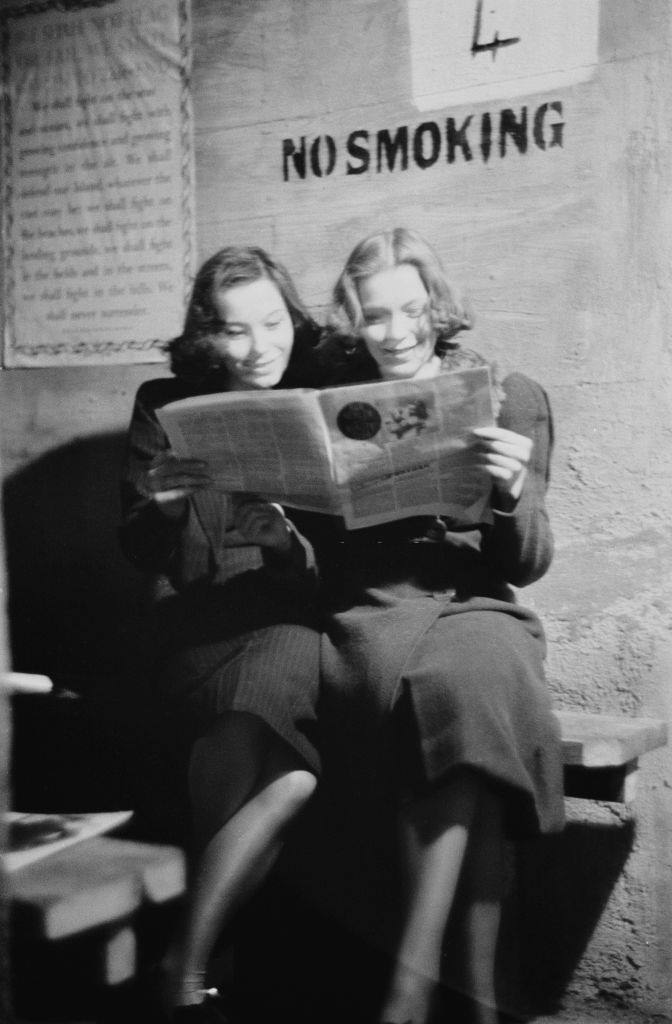

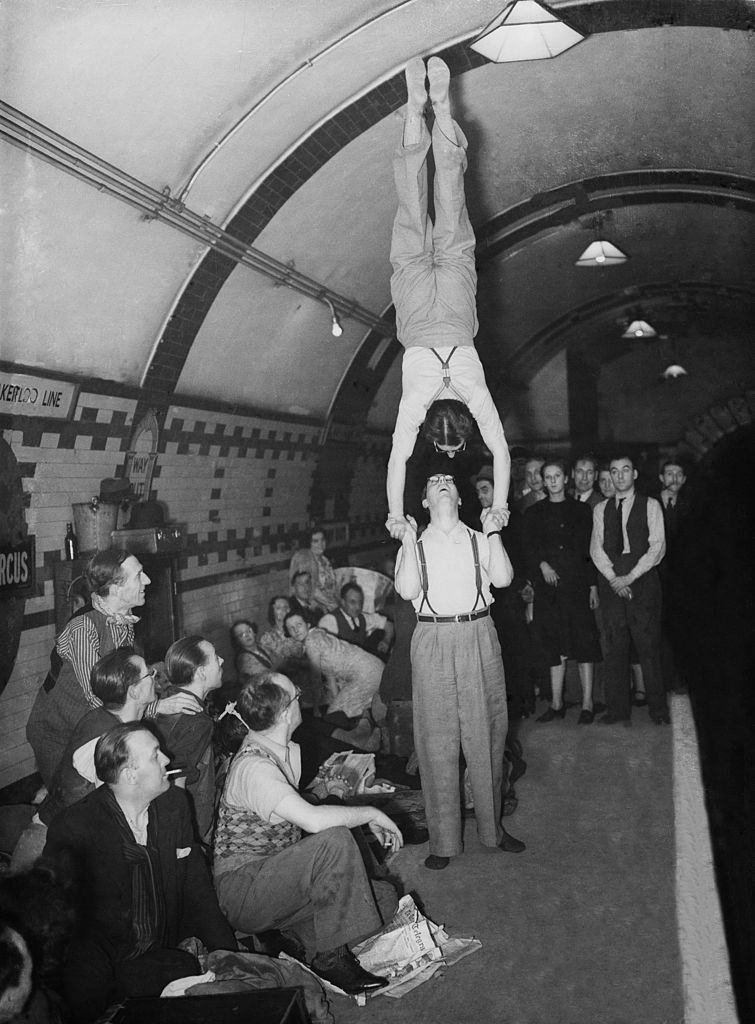

Many large shelters and the Underground were upgraded by the end of 1940. Authorities provided stoves and bathroom facilities, and canteen trains provided food. To reduce time spent queuing, tickets were issued for bunks in large shelters. The Salvation Army and the Red Cross formed committees within shelters to improve conditions. Concerts, films, plays, and books from local libraries were entertainment. Even during the period of the greatest bombing of September 1940, when the bombing intensity was not as high as pre-war expectations, the Blitz caused no psychiatric crisis.