At the turn of the 20th century, London stood as a vast, energetic metropolis, the capital city of the extensive British Empire. Amidst the ceaseless activity of its streets, the mix of grand buildings and modest homes, and the diverse population, hundreds of churches marked the cityscape. These structures served as places of worship for various Christian communities and represented different architectural designs spanning centuries of London’s rich and complex history.

Looking across the London skyline during this period, the spires, towers, and domes of churches were prominent features. They rose above the rows of terraced houses and bustling commercial streets, signifying the presence of established parishes and congregations. The sheer number of churches was remarkable, catering to the spiritual needs of a large population. While the Church of England (Anglican) had a significant presence with numerous parish churches and cathedrals, London was also home to many other denominations. Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Roman Catholics, and other groups all had their own places of worship scattered across the capital.

Read more

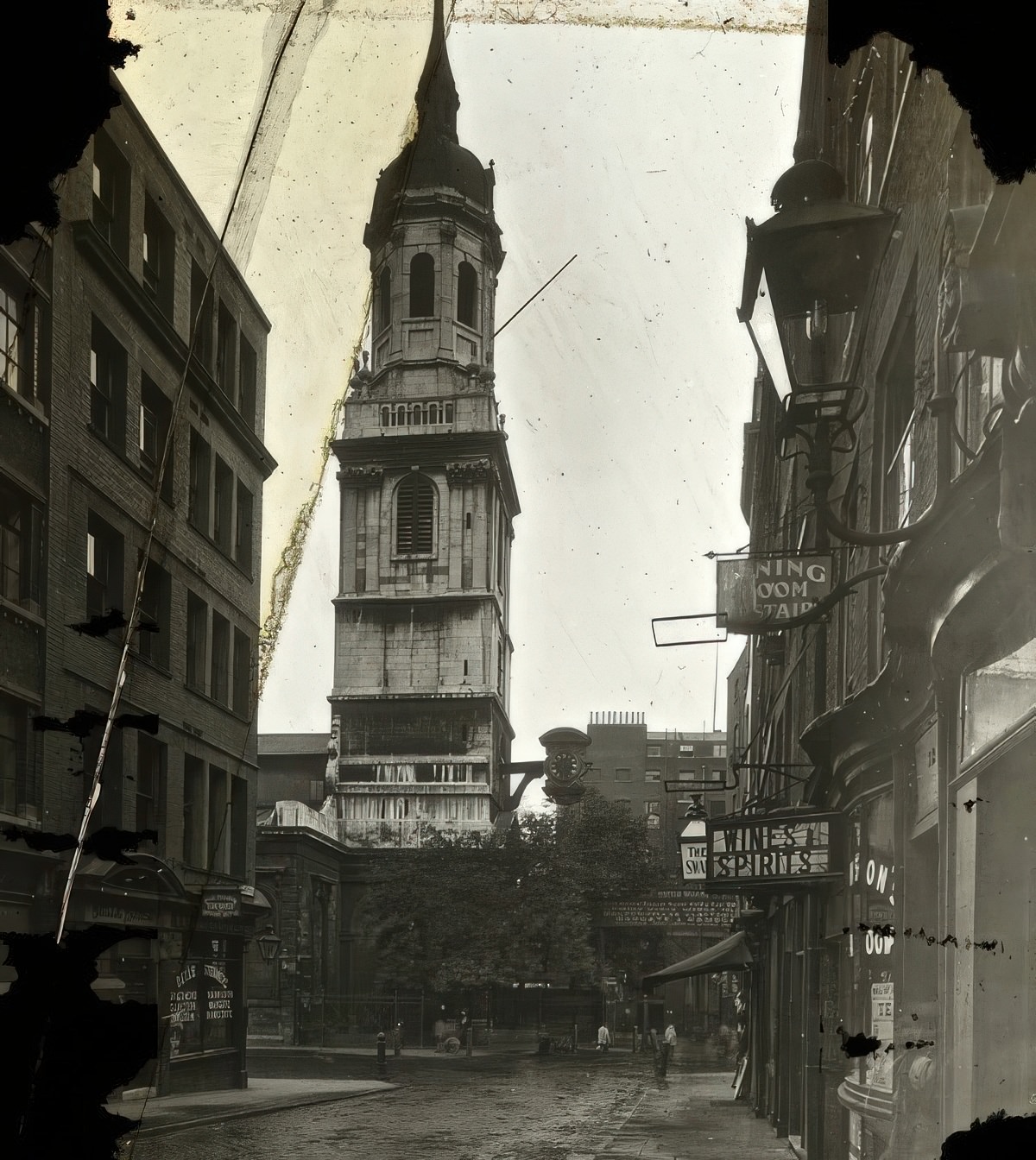

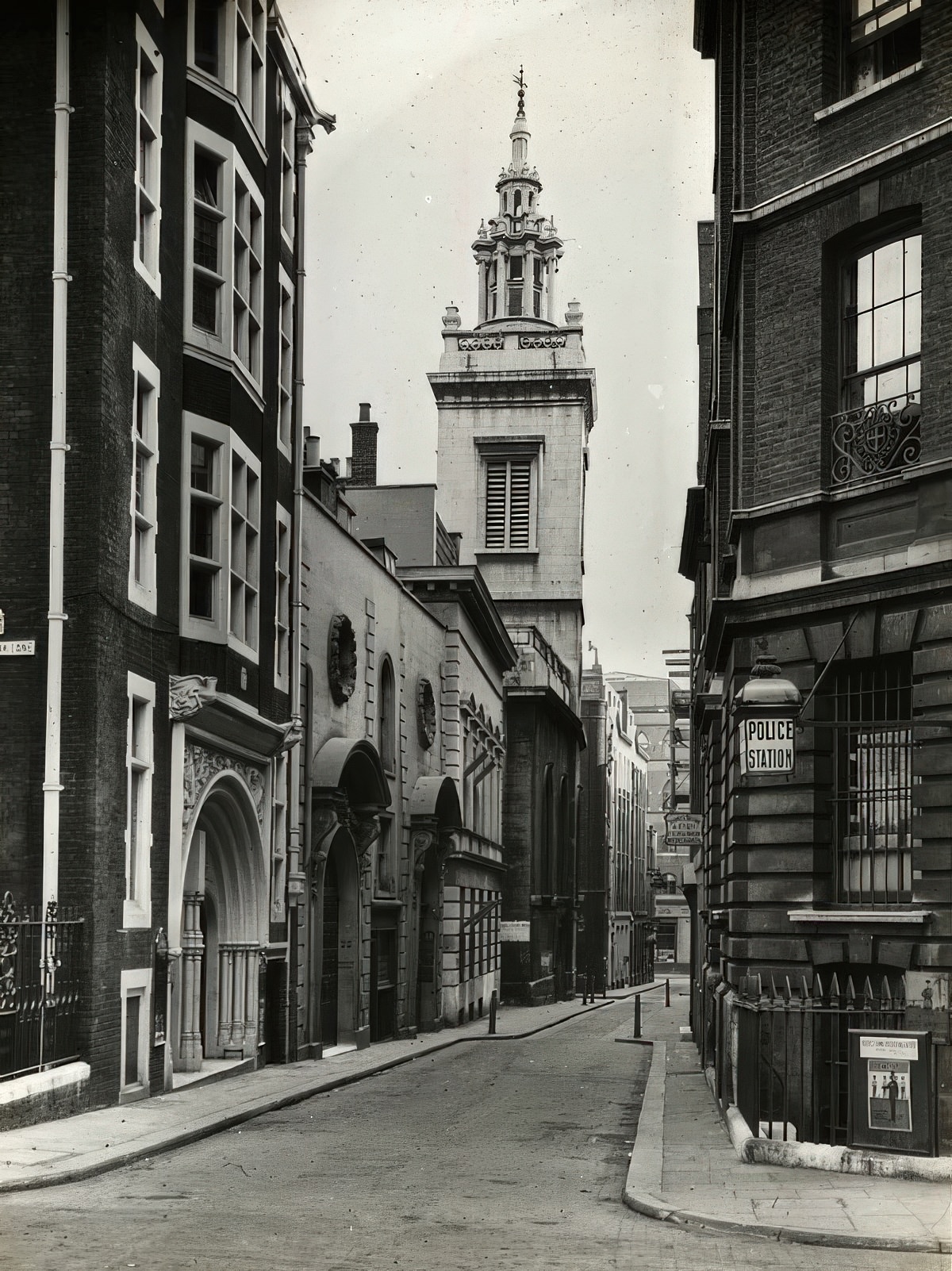

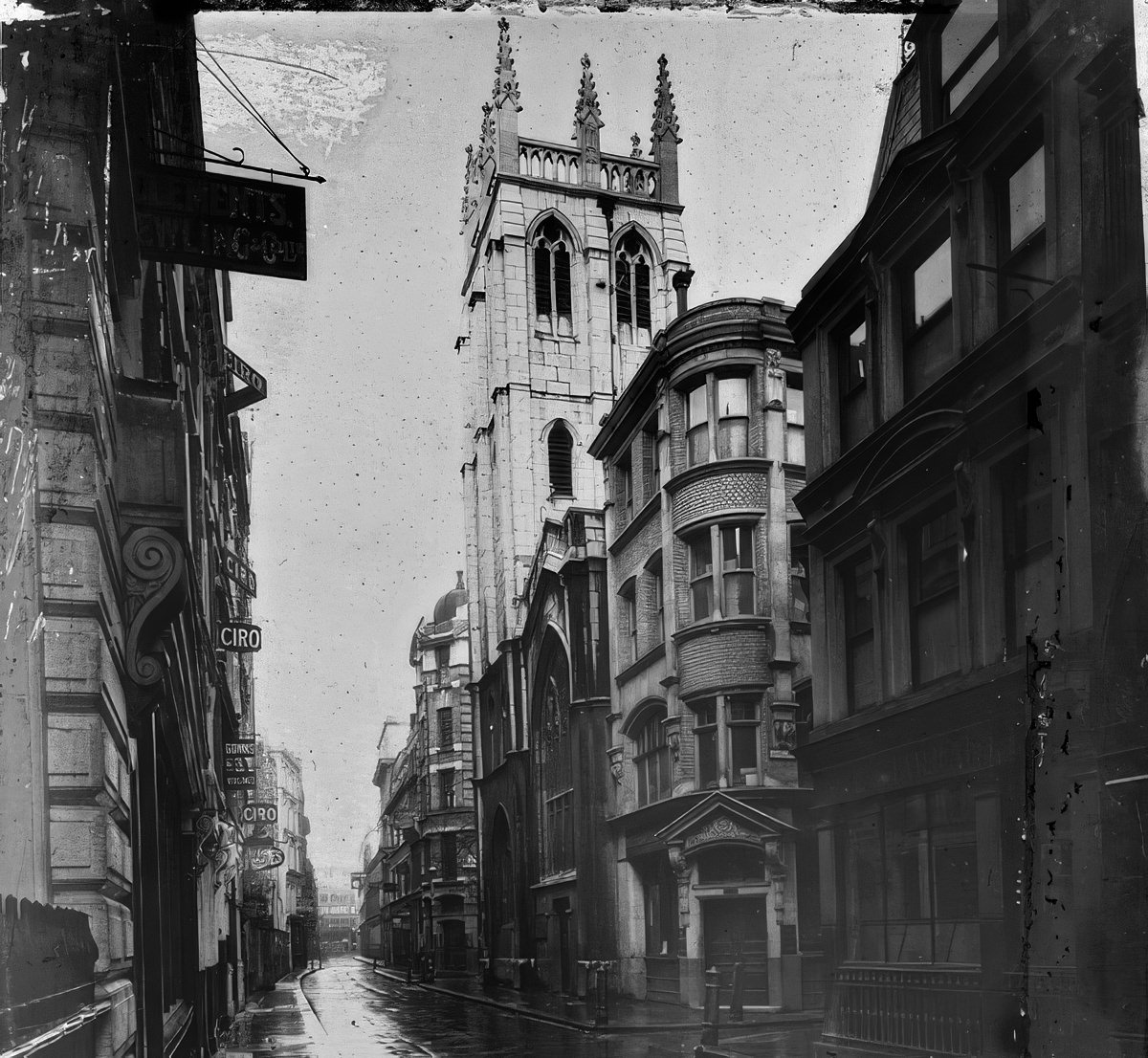

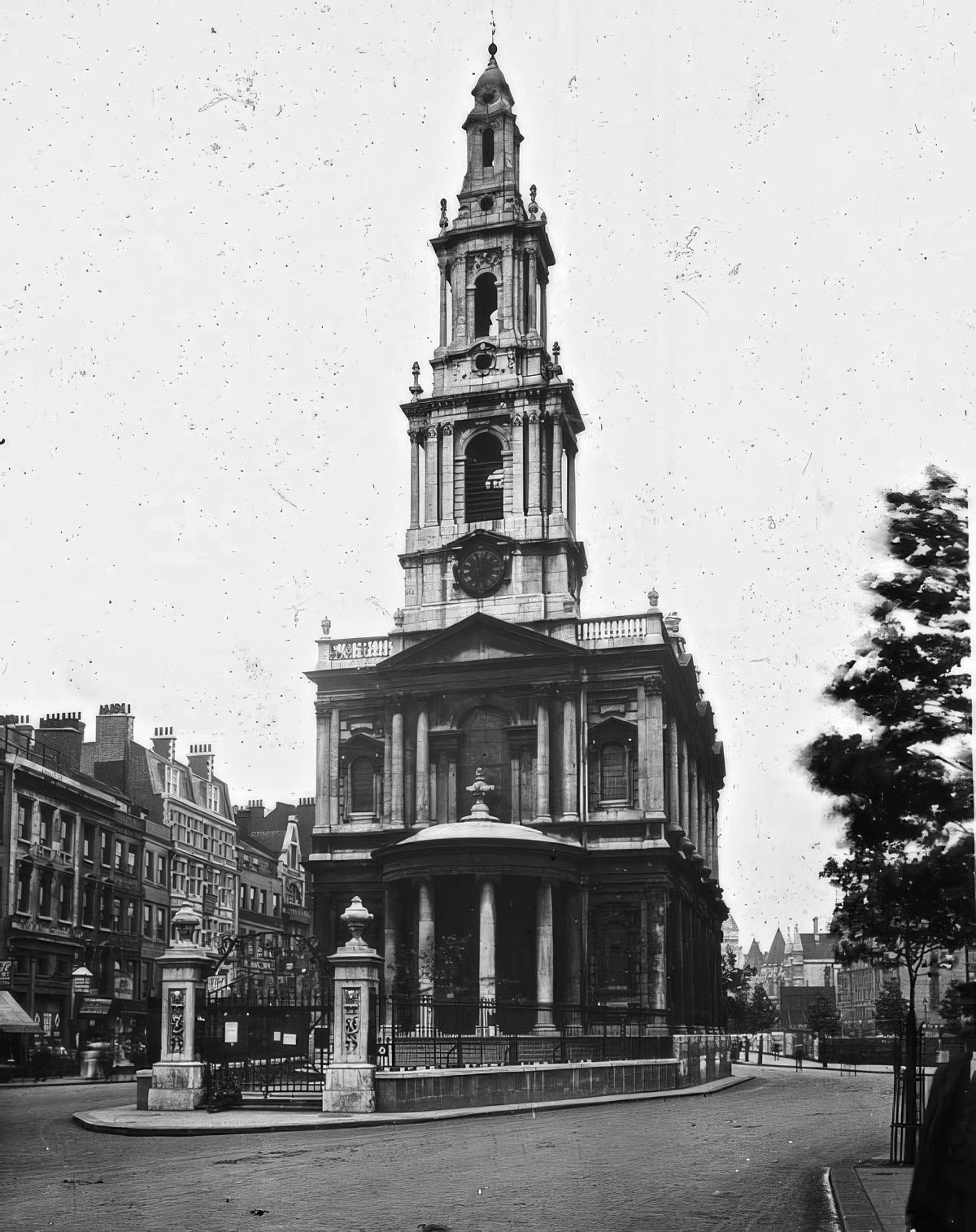

The architectural styles of London’s churches told a story of the city’s development. Visitors could find ancient structures displaying the characteristics of Gothic architecture – features like pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and large windows often filled with stained glass, most famously represented by Westminster Abbey. A great number of churches, particularly within the historic Square Mile or City of London, showcased the elegant Baroque style. Many of these were designed by Sir Christopher Wren and his contemporaries in the decades following the Great Fire of London in 1666, often recognizable by their distinctive steeples, classical columns, and sometimes domed interiors. The 19th century, a period of rapid growth and religious revival known as the Victorian era, had added substantially to London’s church landscape. Numerous churches were built during this time, frequently designed in a Neo-Gothic or Gothic Revival style, echoing medieval designs but often on a grand scale with intricate details. A significant and relatively new landmark representing a different tradition was Westminster Cathedral, the mother church of the Catholic Church in England and Wales. Its construction, largely completed by 1903, introduced a striking Byzantine-inspired style to London, characterized by its striped brick and stonework exterior, numerous domes, and tall campanile or bell tower.

Certain churches were already globally recognized landmarks. St. Paul’s Cathedral, Wren’s masterpiece with its iconic dome, presided over the city. Westminster Abbey, steeped in history as the setting for coronations, royal weddings, and burials for centuries, was a site of national importance. Beyond these monumental buildings existed the vast network of parish churches. Wren’s elegant city churches continued to serve the financial district, while the churches built during the Victorian era catered to the populations of London’s expanding suburbs. Each church, large or small, often served as a focal point for its immediate neighborhood, its identity tied to the local community.

Stepping inside these diverse churches revealed a range of atmospheres. High Church Anglican parishes and Roman Catholic churches often featured rich interior decorations. Visitors might find elaborate altars, carved wooden screens and choir stalls, polished brass fixtures, religious statues or paintings, and vibrant stained-glass windows depicting biblical scenes and saints. Many Victorian-era churches were particularly noted for their extensive and colorful stained glass. In contrast, some churches, particularly chapels belonging to non-conformist denominations like Methodists or Baptists, often presented much plainer interiors. These spaces might emphasize simplicity, with less ornamentation, focusing attention on the pulpit for preaching and communal singing. Rows of wooden pews typically filled the main body of the church, facing towards the east end or the pulpit. Stone tablets and memorials affixed to the walls often commemorated prominent local figures or past members of the congregation. In the early 1900s, lighting inside churches was commonly provided by gas lamps, although the newer technology of electric lighting was beginning to be installed in some buildings.

Church buildings were far from static monuments; they were active centers within their communities. The sound of church bells was a familiar part of London’s soundscape, especially on Sundays and special occasions, calling people to attend services. Regular worship services formed the backbone of church life, marking Sundays, religious festivals like Easter and Christmas, and other holy days. Churches were also the traditional venues for key life events – christenings and baptisms for infants, weddings celebrating new unions, and funerals mourning the deceased. Beyond religious services, many churches functioned as community hubs. They might run Sunday schools for children’s religious education, organize charitable activities to support the poor and needy in the parish, host social clubs and meetings, and hold bazaars or concerts.

Externally, many of London’s older churches, particularly those constructed from lighter-colored stone such as the Portland limestone favored by Wren, bore the marks of the city’s atmosphere. Decades of coal smoke from homes and industry often left stone surfaces darkened with soot, requiring periodic cleaning and restoration efforts. These varied church buildings, with their spires and towers, sturdy stone walls, and arched windows, stood as familiar fixtures in the London streetscape of the early 1900s. They shared the roads with horse-drawn omnibuses and carts, the increasingly common motor car, delivery wagons, and pedestrians going about their daily lives, serving as enduring symbols of faith and community amidst the ever-changing city.