Kindertransport (German for “Children Transport”) was a nine-month rescue program by the British Government started in the late-1930s. It rescued thousands of children under 17, primarily Jewish, from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Danzig’s free city (Gdańsk) by relocating them to the United Kingdom. After the German Pogroms of November 9-10, 1938, the program began when they attacked Jews and confiscated their properties. The program ended when World War II started; however, children were rescued until 1941.

Following Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933, tens of thousands of Jews fled the country. However, as acquiring a visa became increasingly tricky, emigration began to slow. A delegation from 32 countries met for ten days in Évian-les-Bains, France, starting on July 6, 1938. The Évian Conference achieved little despite grand proclamations. There were discussions of possible settlement locations, but most countries remained unwilling to accept new immigrants. In response to the British Jewish Refugee Committee’s calls for action following Kristallnacht, the British Parliament held a debate in the House of Commons on November 21, 1938.

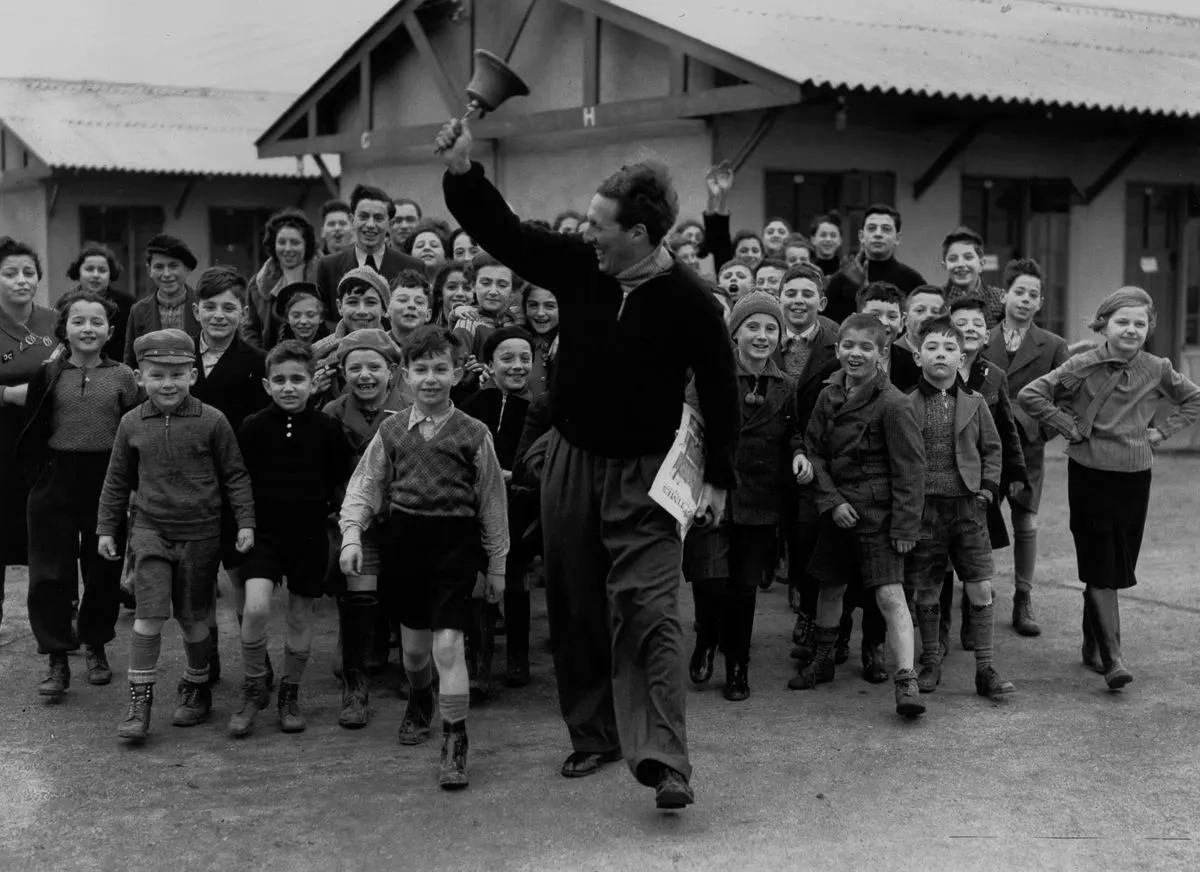

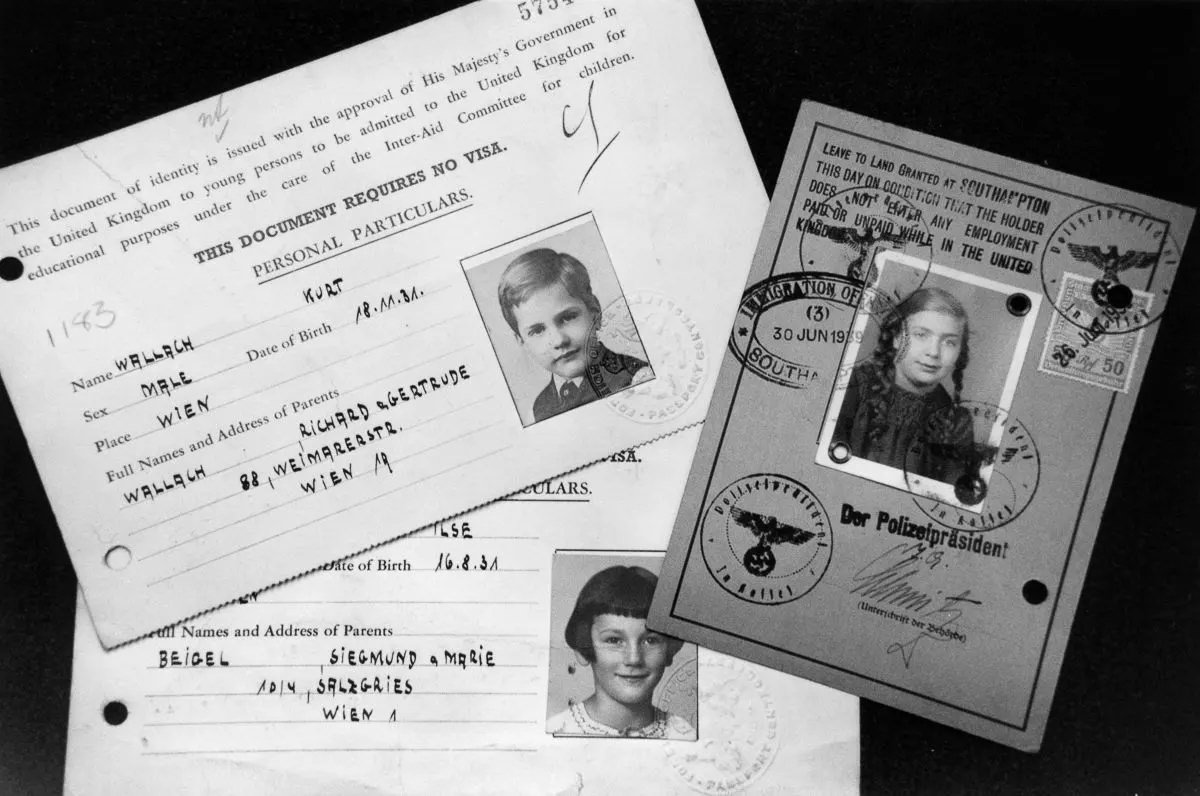

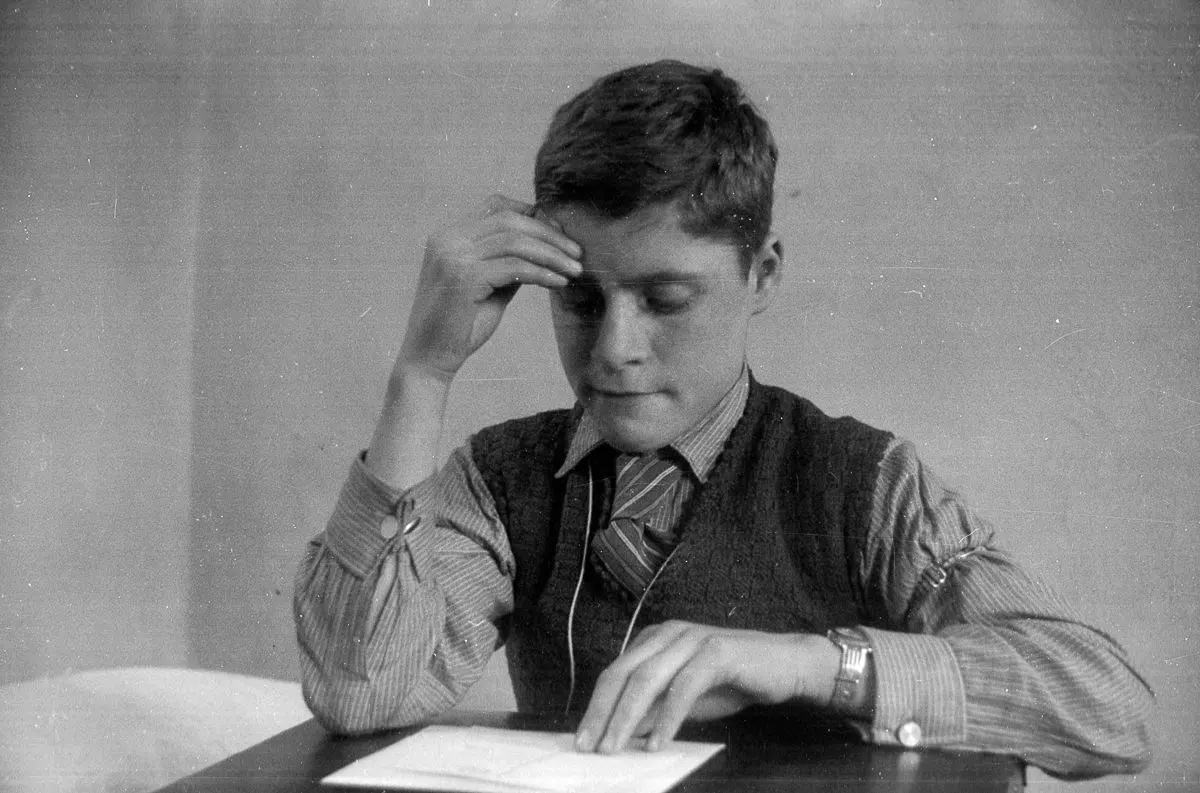

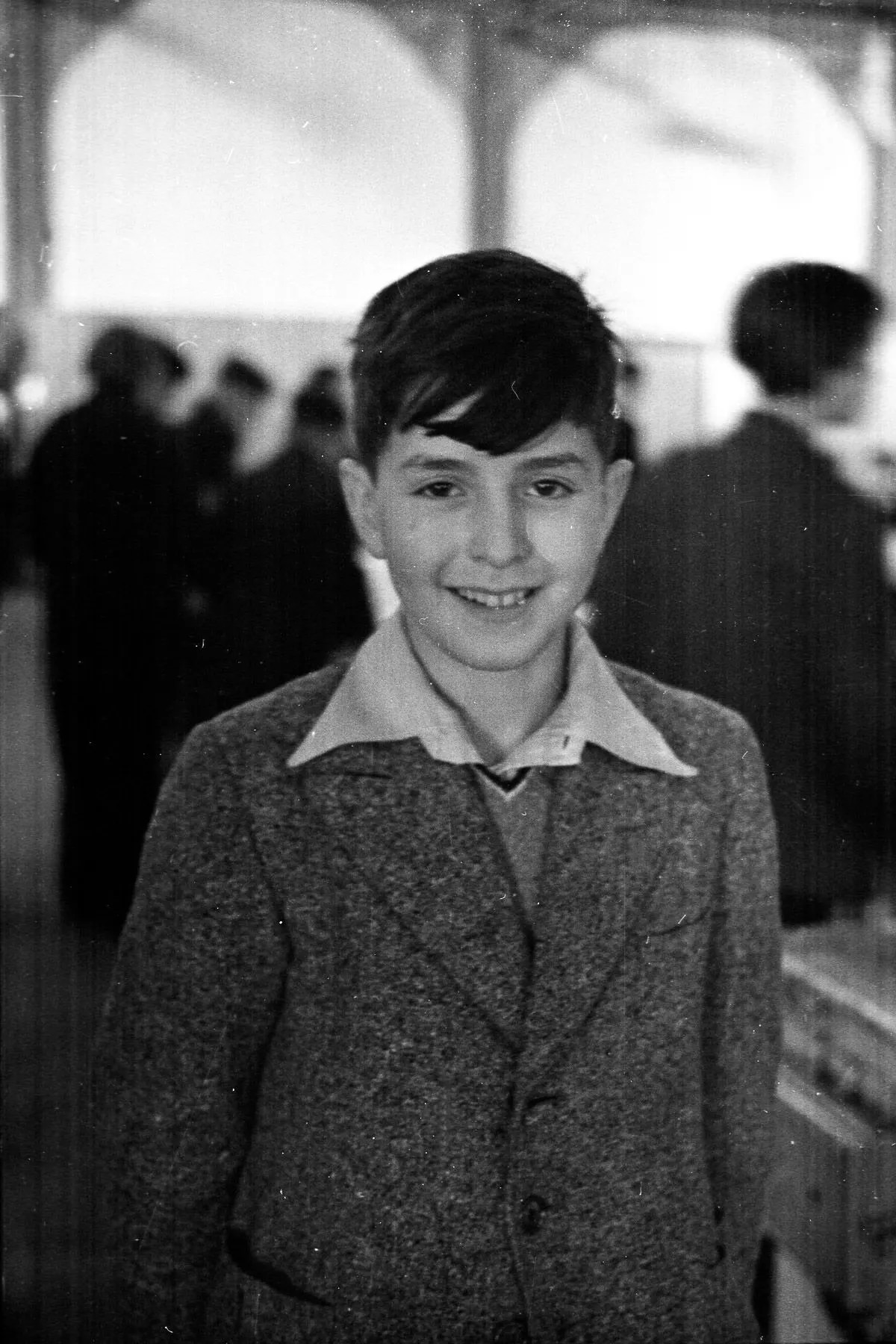

The British Empire occupied Palestine in 1917, and it was a part of their colonial empire at that time. So they decided to send these Jewish immigrants to Palestine. The decision to allow an unspecified number of children under the age of 17 into the United Kingdom was influenced by several factors: the advocacy of refugees, growing awareness of anti-Jewish atrocities in Germany and Austria, and immigration sympathies among some high-ranking Britons. Each of these children had to post a £50 bond to “ensure their ultimate resettlement” since they were assumed to reconnect with their parents after the crisis passed. They were given temporary travel documents. The first transport left Germany less than one month after Kristallnacht, on December 1, 1938. It brought 196 Jewish children from a Berlin orphanage destroyed on November 9 by the Nazis. During their extensive Kindertransport experience, the children experienced extreme trauma. The specific details of the child’s trauma and how it was experienced depended on his age at separation and the details of their experience until the end of the war and even afterwards. The younger children had no developed sense of time, and for them, the trauma of separation was total from the very beginning. The second cause of stress had to learn a new language in a country where the child’s native language was not understood.

In the aftermath of the war, children from the Kindertransport had great difficulty reuniting with their families in Britain. There was a flood of requests from children seeking to find their parents or a surviving family member. Many of the children were reunited with their families by traveling to far-off countries. Others learned that their parents had not survived the war.

Mona Golabek describes in her novel about the Kindertransport titled The Children of Willesden Lane how the children who had no families left had to leave the homes they had acquired in boarding houses in order to make room for younger children flooding the country. Future Nobel laureates Arno Penzias and Walter Kohn were among the children saved by the Kindertransport, along with many others who, despite losing everything, became prominent scientists, politicians, and artists.