The 19th century, spanning the years 1801 to 1900, was a period of immense and often tumultuous change across the vast Indian subcontinent. This era saw the fading power of existing empires, the dramatic expansion and consolidation of British control, significant shifts in the economy and society, and the first stirrings of modern Indian nationalism. For the millions living across its diverse regions, life was profoundly shaped by these overlapping forces.

Shifting Political Control

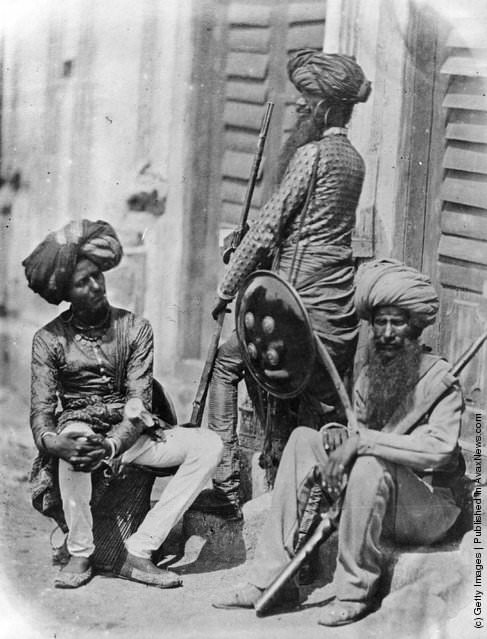

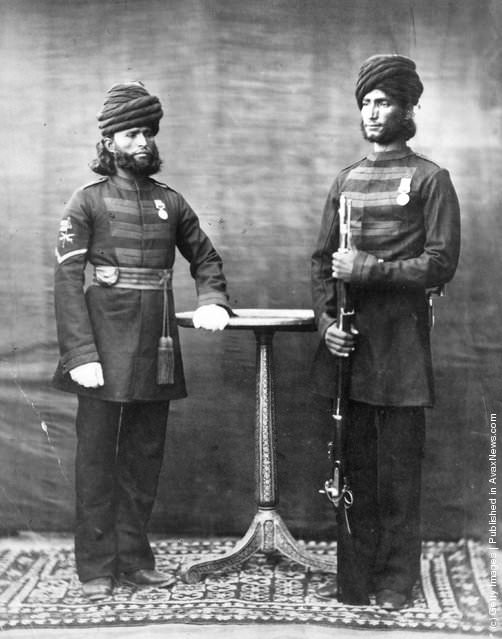

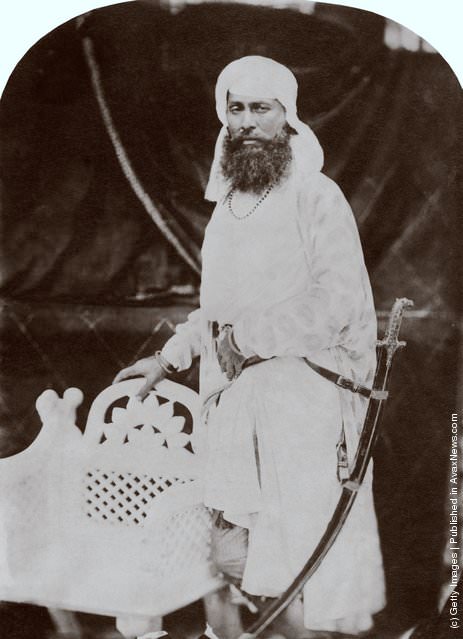

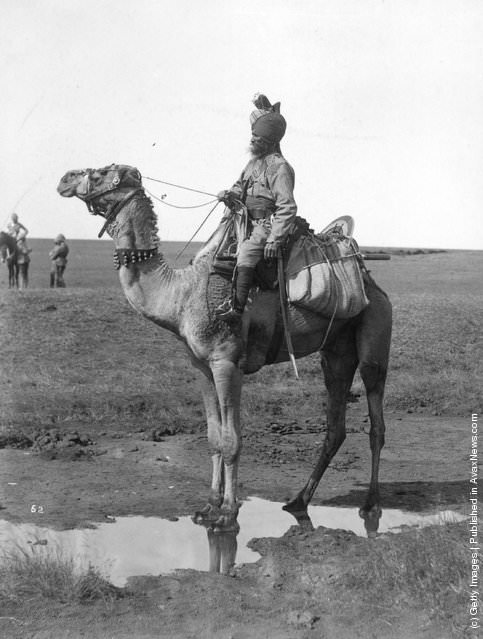

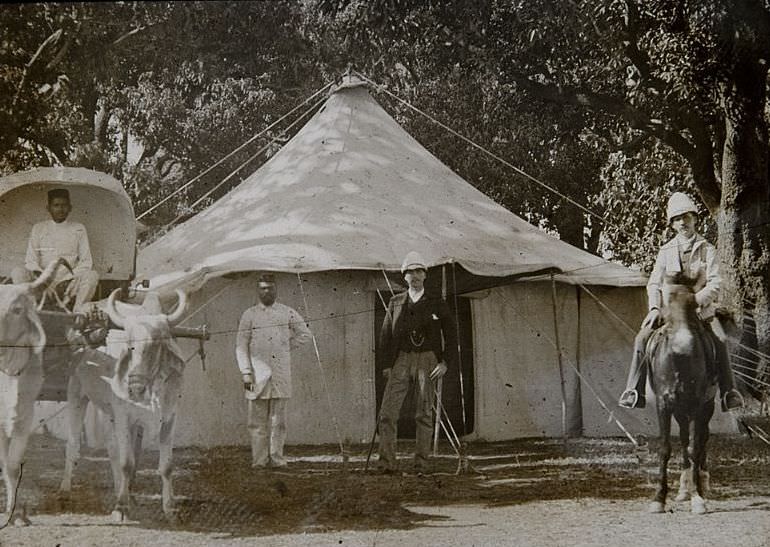

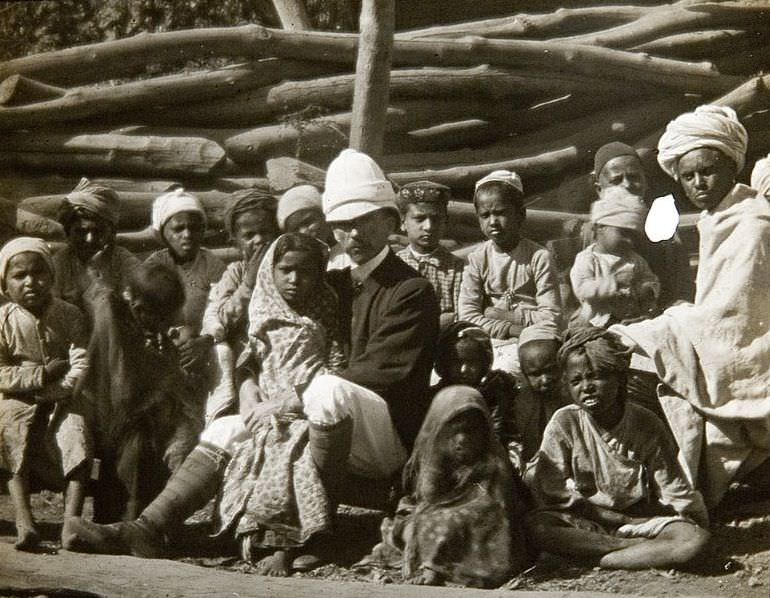

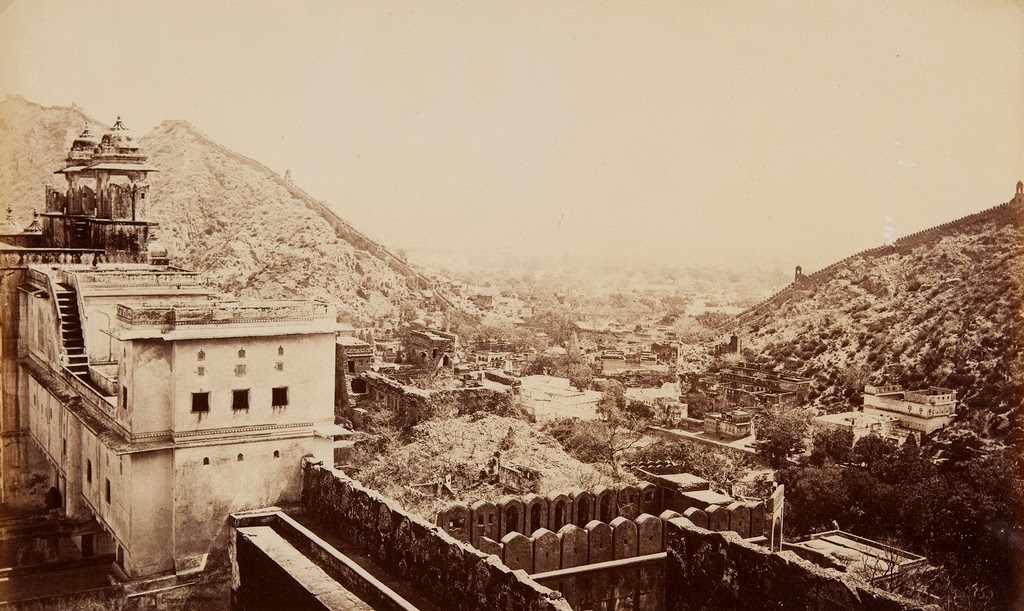

As the century began, the British East India Company, initially a trading entity, was rapidly transforming into a major political and military power in India. It steadily expanded its territories through warfare, treaties, and strategic alliances, gradually eclipsing the authority of the declining Mughal Empire based in Delhi and challenging strong regional powers like the Maratha Confederacy and the Sikh Empire. By the mid-1800s, the East India Company had become the dominant force across much of the subcontinent. Discontent over Company policies, annexation practices, and cultural insensitivities boiled over in the large-scale Indian Rebellion of 1857. This major uprising, initiated by Indian soldiers (sepoys) in the Company’s army but spreading to include civilians, shook British control. After the rebellion was forcefully suppressed, the British government dissolved the East India Company and assumed direct rule over its Indian territories in 1858. This marked the beginning of the British Raj, with India governed directly by the British Crown through an appointed official called the Viceroy. In 1877, Queen Victoria was formally proclaimed Empress of India. The political landscape under the Raj was divided: large parts of India were directly administered by British officials (“British India”), while other areas remained as princely states, ruled by hereditary Indian princes (Maharajas, Nawabs, Nizams) who accepted British paramountcy.

Read more

Life in Towns and Villages

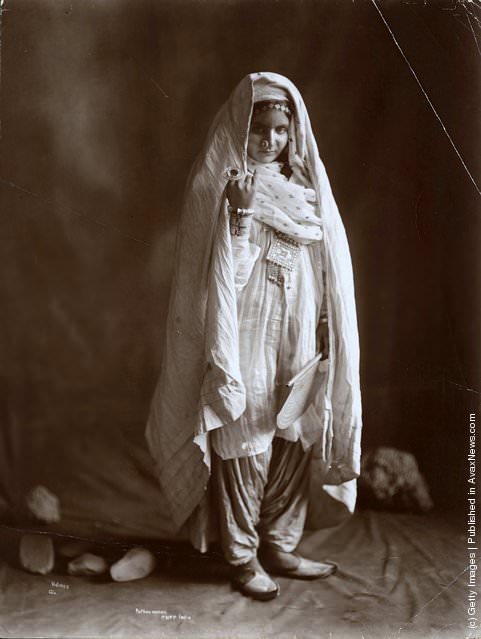

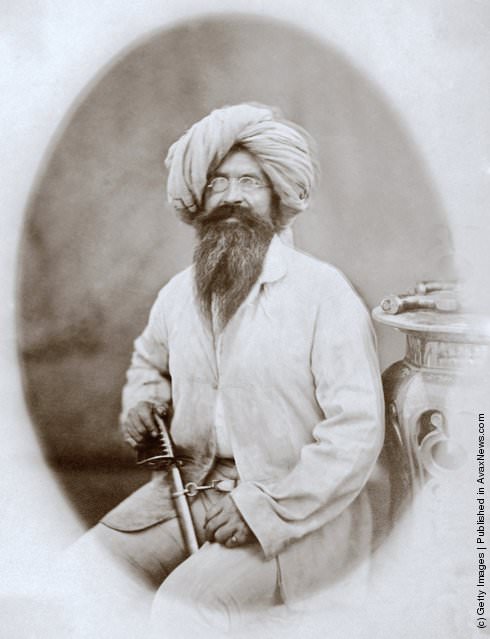

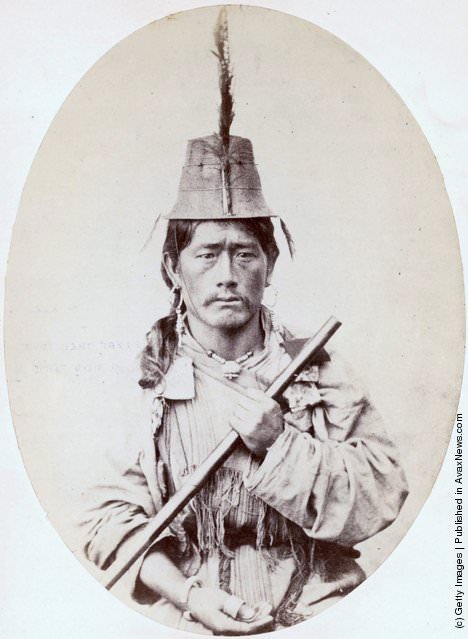

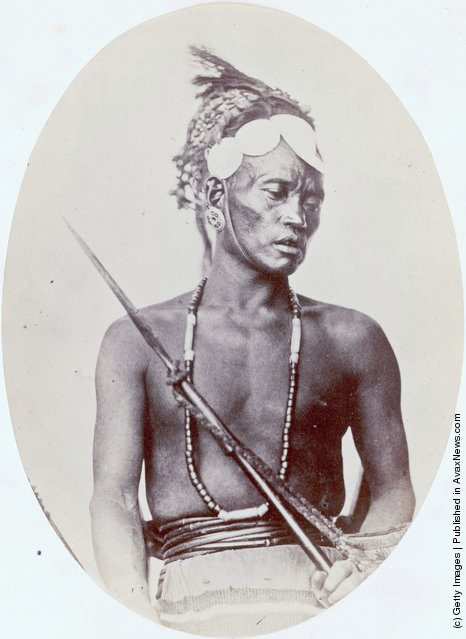

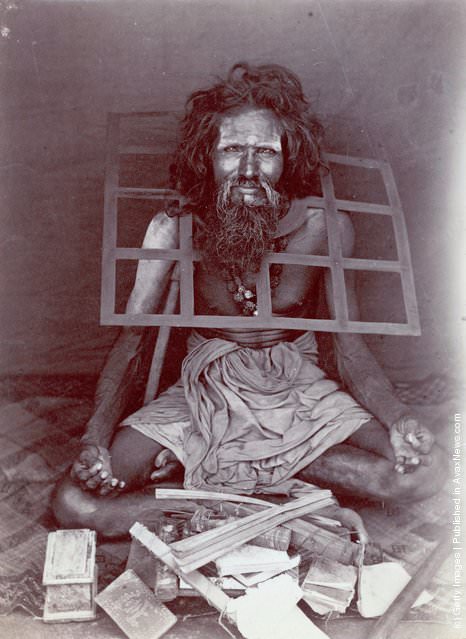

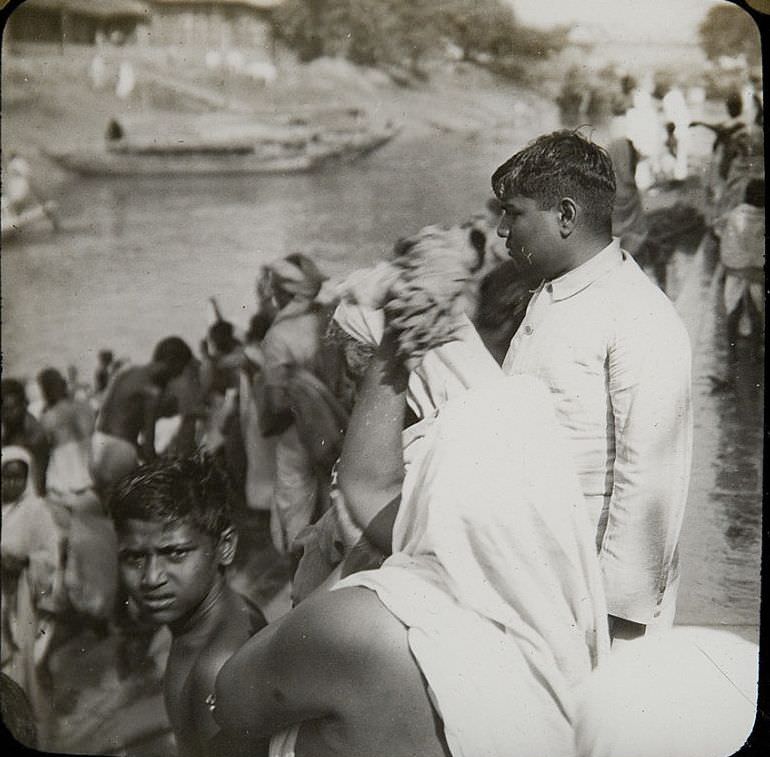

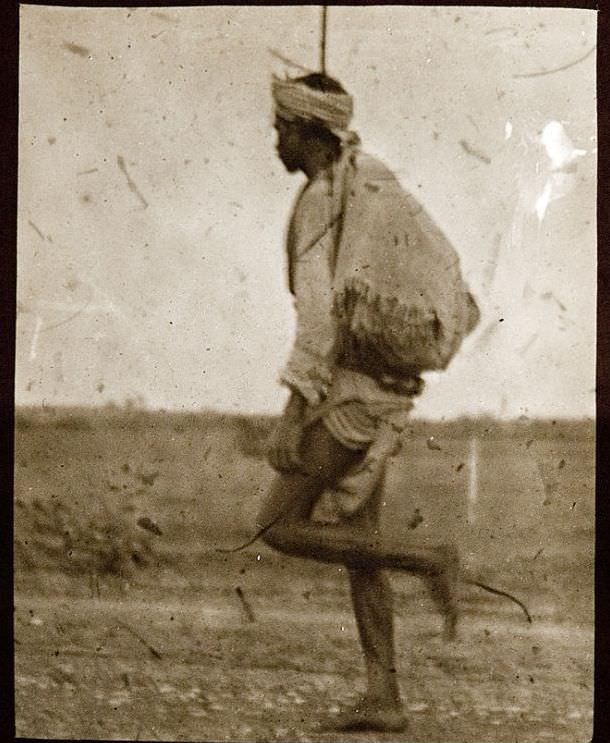

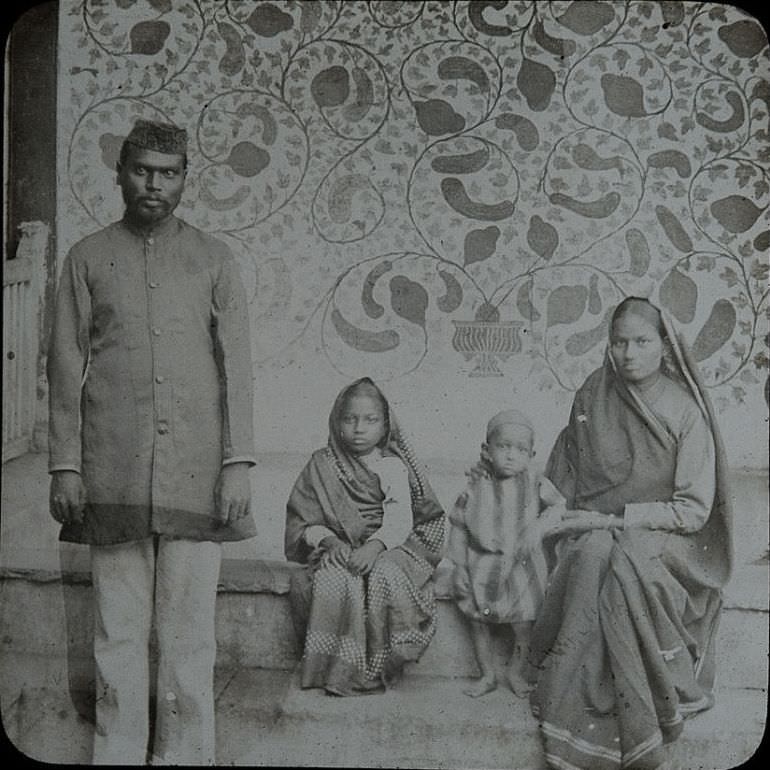

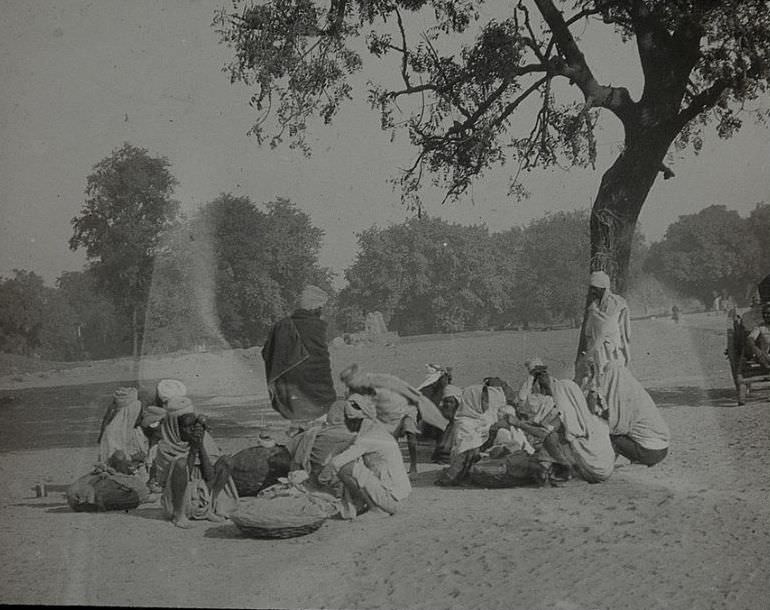

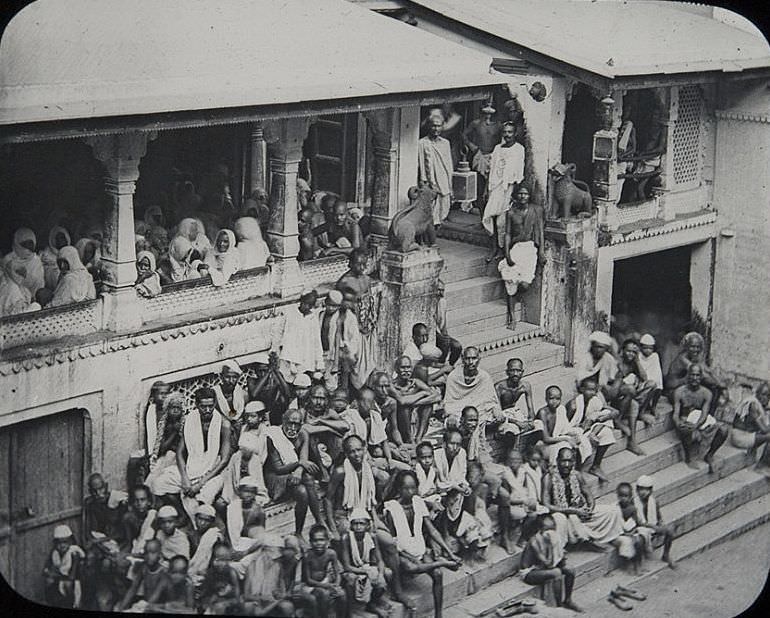

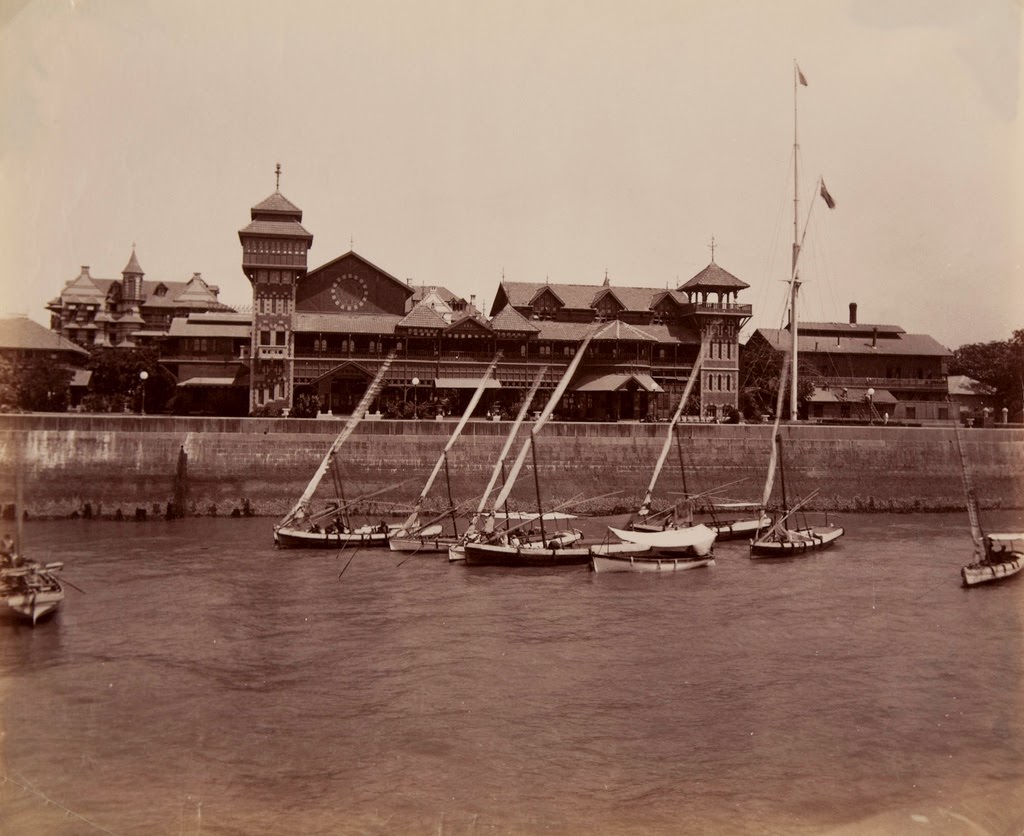

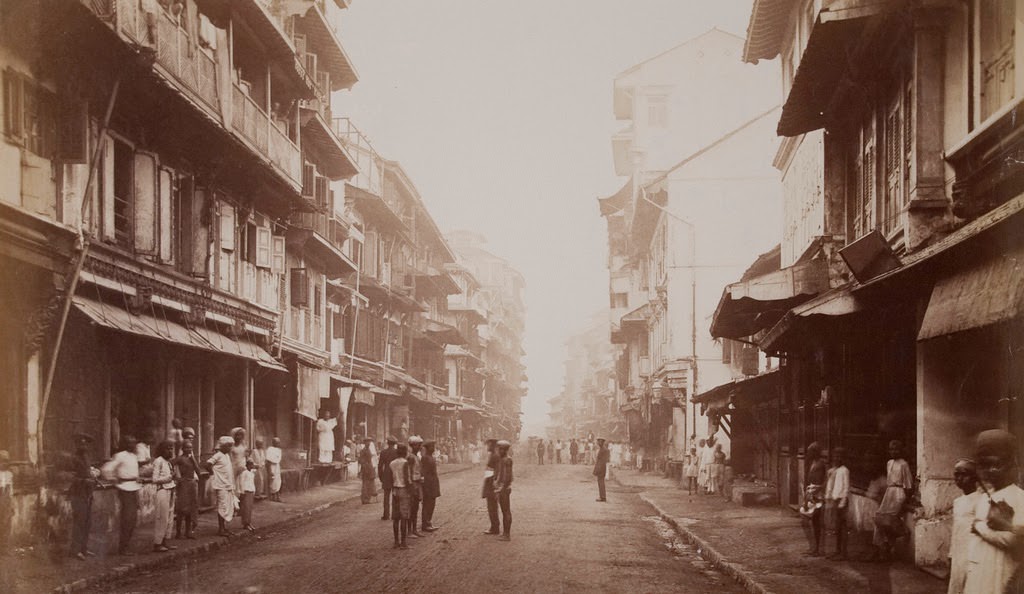

Throughout the 19th century, India remained overwhelmingly rural. The majority of the population lived in villages, with agriculture forming the backbone of their existence. Daily life was deeply intertwined with agricultural seasons, local customs, and established social structures, including the complex hierarchy of the caste system and diverse religious practices – predominantly Hinduism and Islam, but also significant populations following Sikhism, Jainism, Buddhism, Christianity, and other faiths. While village life predominated, key port cities like Calcutta (Kolkata), Bombay (Mumbai), and Madras (Chennai) experienced significant growth under British influence, becoming major centers of trade, administration, and emerging industries.

Economic Landscape

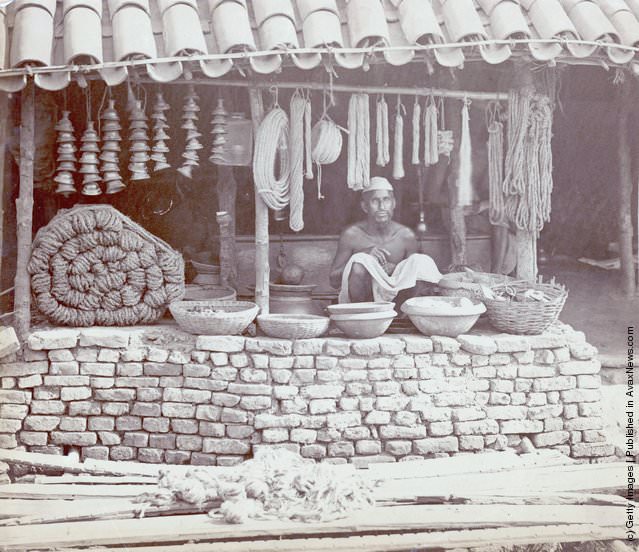

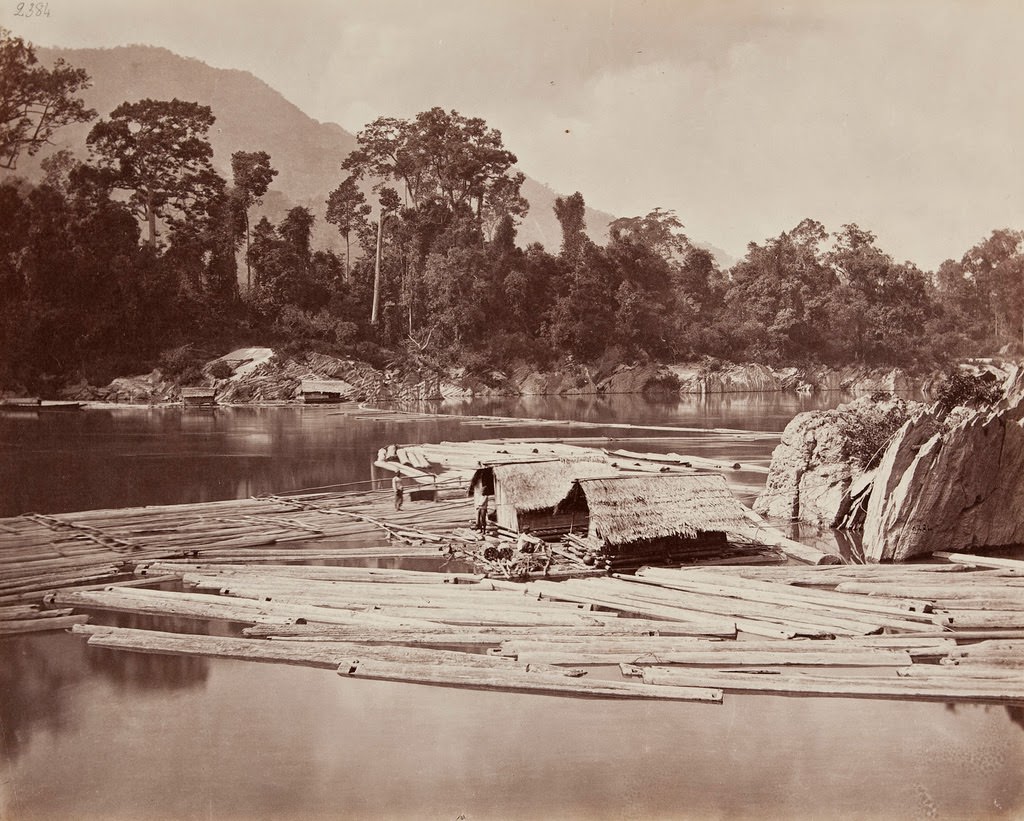

India’s economy during this period was primarily based on agriculture. Farmers cultivated food grains for local consumption, alongside important cash crops such as cotton, jute (for sacking and ropes), indigo (a blue dye), tea, and opium (which the British traded extensively, particularly with China). However, India’s renowned traditional industries, especially handloom textile production, suffered a severe decline during the 19th century. This was largely due to the influx of cheaper, factory-made textiles imported from Britain following the Industrial Revolution. The British administration focused on developing infrastructure projects that primarily served their economic and strategic interests. An extensive railway network was built across India, especially rapidly after the 1857 Rebellion, facilitating the movement of troops and the transport of raw materials to ports for export. Telegraph lines were also established for faster communication. New land revenue systems implemented by the British often required fixed cash payments from peasants, which could lead to debt and hardship, particularly during poor harvest years. The century witnessed several devastating famines in different regions, causing immense suffering and loss of life.

Social Changes and Reform

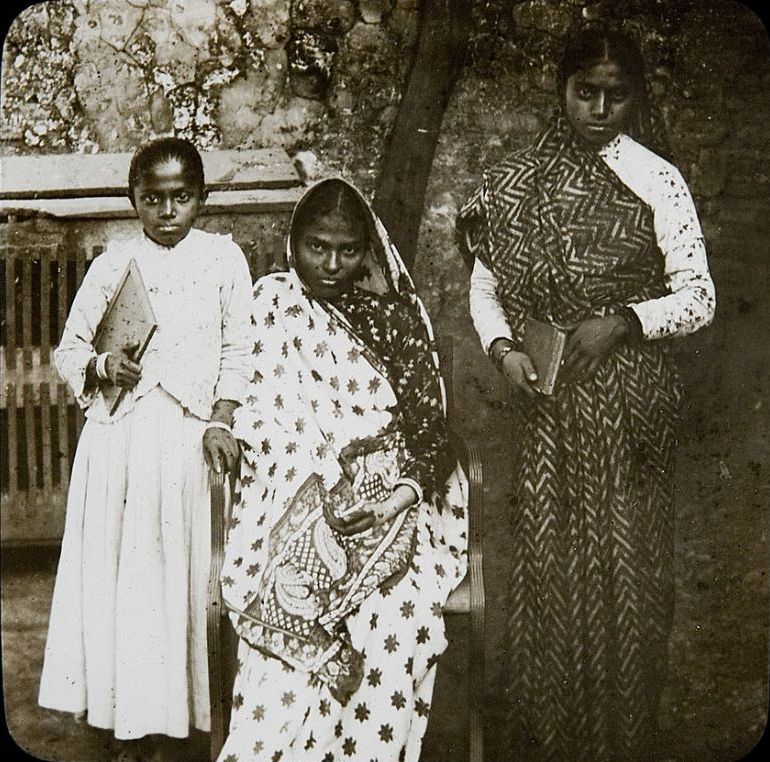

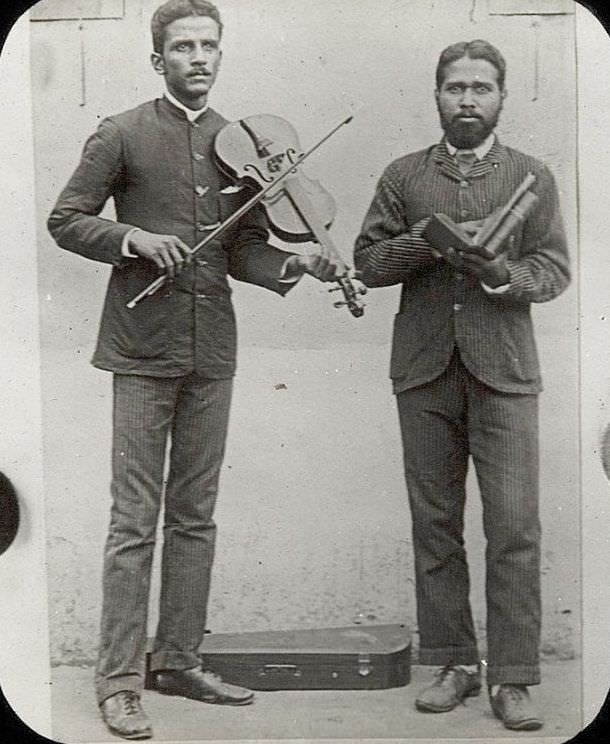

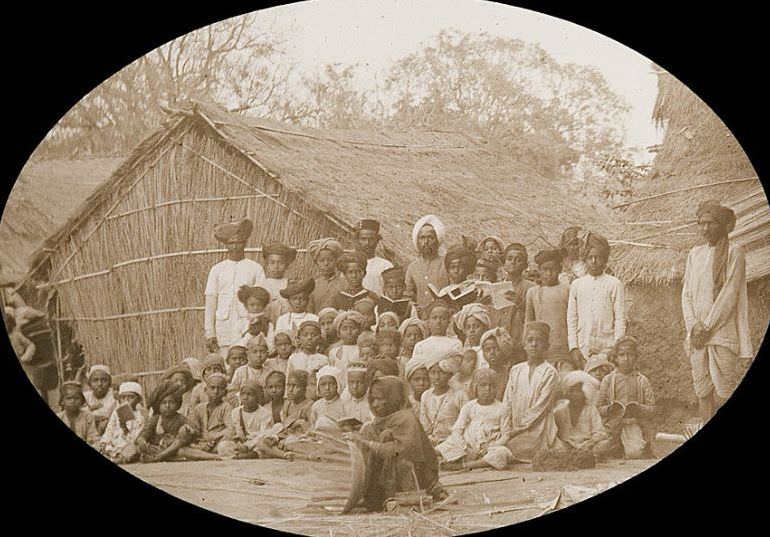

The 19th century was also a time of significant social ferment and the beginning of modernization in some spheres. The British introduced Western-style education through schools and universities, initially aiming to train Indians for roles in the colonial administration. This exposure to Western ideas of liberalism, reason, and social justice influenced a generation of educated Indians. Concurrently, important social reform movements emerged from within Indian society itself, led by prominent intellectuals and activists like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Jyotirao Phule. These reformers challenged certain traditional customs, campaigned against practices like *sati* (the immolation of widows, eventually banned by the British in 1829), advocated for widow remarriage, questioned the rigidities of the caste system, and promoted education, including for girls and women.

Seeds of Nationalism

The experiences of living under foreign rule – including economic exploitation, perceived racial discrimination, and limited opportunities in higher levels of government – combined with the influence of Western political thought learned through the new education system, gradually fostered a sense of shared identity and nascent nationalism among some sections of the Indian population. Early political associations began to form, initially focused on seeking reforms and greater representation within the existing British framework. A landmark event was the founding of the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1885. Primarily composed of educated, middle-class Indians at its inception, the INC provided a platform for articulating Indian grievances and aspirations, laying the groundwork for the larger independence movements of the 20th century.