In the dense jungles of Lubang Island, Philippines, there’s a story about a soldier who showed incredible loyalty and dedication to his duty, even 30 years after World War II was over. This is the story of Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese Imperial Army intelligence officer who continued to fight a war that had long been over, refusing to surrender until 1974, nearly 29 years after the Japanese had officially capitulated.

The Unyielding Soldier

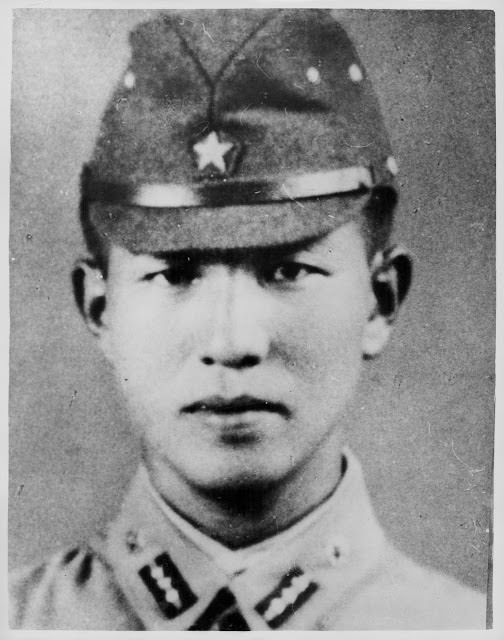

Hiroo Onoda’s journey into history began on December 26, 1944, when he was deployed to Lubang Island. Coming from a lineage of the ancient Samurai warrior class, Onoda was imbued with a profound sense of loyalty and honor. These principles were the bedrock of his existence and his service. Trained in commando tactics, he was ordered never to surrender or take his own life, but rather to continue guerrilla warfare until officially relieved of duty. He was given a clear mandate: remain behind enemy lines, sabotage operations, and, most importantly, never surrender.

After the Allies captured Lubang Island a few months post Onoda’s deployment, he and three other soldiers hid in the deeper parts of the island. Covered by the thick leaves and trees, they managed to avoid being caught and kept on fighting, without knowing that their enemy wasn’t there anymore.

The War Ends, but not for Onoda

In October 1945, mere months after the war had officially ended, Onoda and his comrades stumbled upon a leaflet declaring the war’s conclusion. To them, it was inconceivable that Japan could surrender, and they deemed the leaflet a trap by the enemy. This disbelief in the war’s end was further cemented when Private First Class Yuichi Akatsu, one of Onoda’s groups, left in 1949 and later communicated that he had surrendered and was treated well. Onoda and the remaining soldiers suspected a conspiracy.

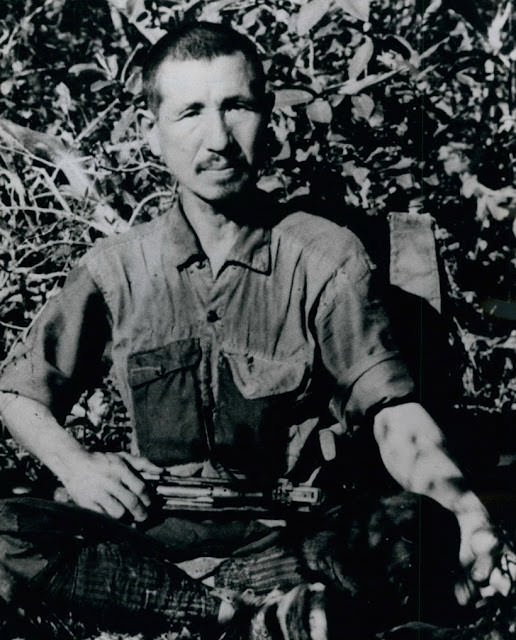

For years, Onoda and his comrades engaged in guerrilla activities, surviving off the land and occasional raids on local villages. Their existence was one of constant vigilance, survival, and adherence to a cause they believed was still just.

Over time, Onoda’s companions were lost. Corporal Shoichi Shimada was killed in 1954, and Kozuka, the last of Onoda’s fellow soldiers, met his end in 1972. Onoda, now alone, continued his campaign, steadfast in his duty.

Throughout the years, various efforts were made to convince Onoda and his companions that the war had ended. Leaflets, news clippings, and even personal letters from their families were dropped from airplanes. Loudspeakers broadcast messages into the jungle, and former comrades pleaded with them to surrender. All were in vain; Onoda viewed these efforts as elaborate enemy tricks.

A Chance Encounter and Surrender

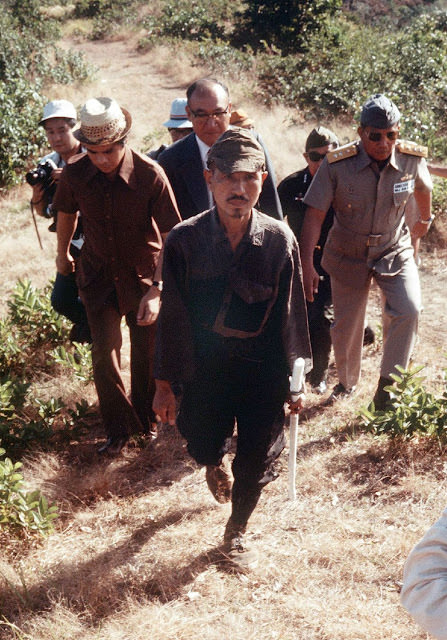

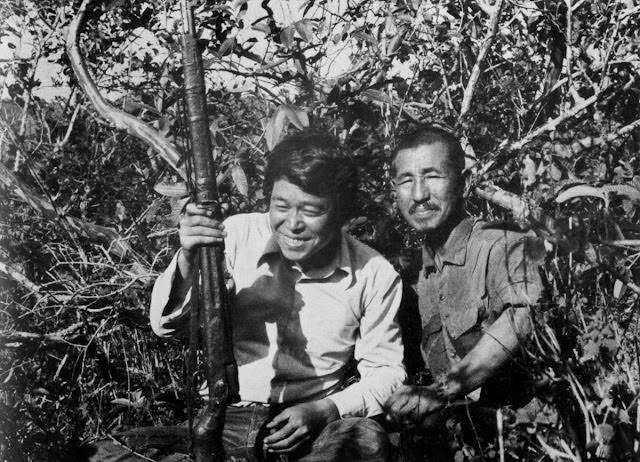

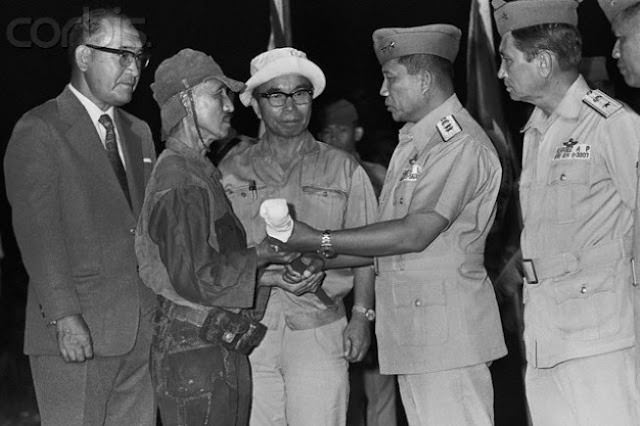

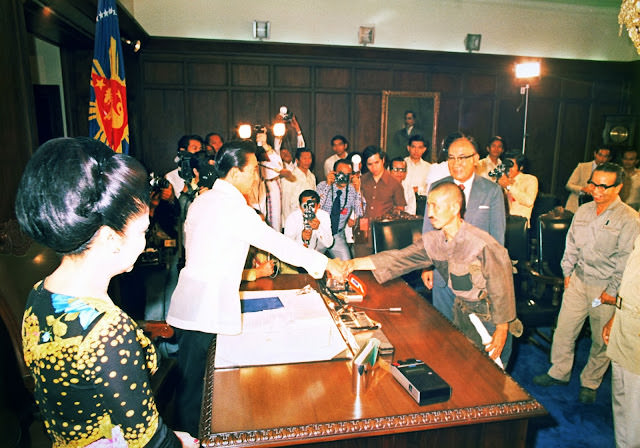

In 1974, Norio Suzuki, a Japanese explorer, found Onoda and attempted to convince him of the war’s end. Onoda, however, remained resolute, stating he could only surrender upon direct orders from a superior officer. Suzuki returned to Japan and, with the government’s help, located Onoda’s former commander, Major Taniguchi, who had since become a civilian.

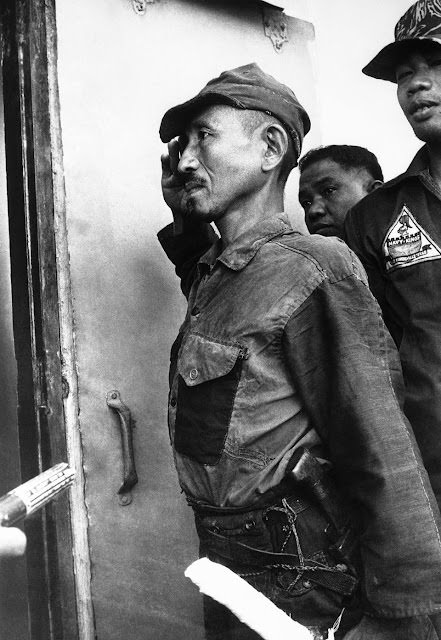

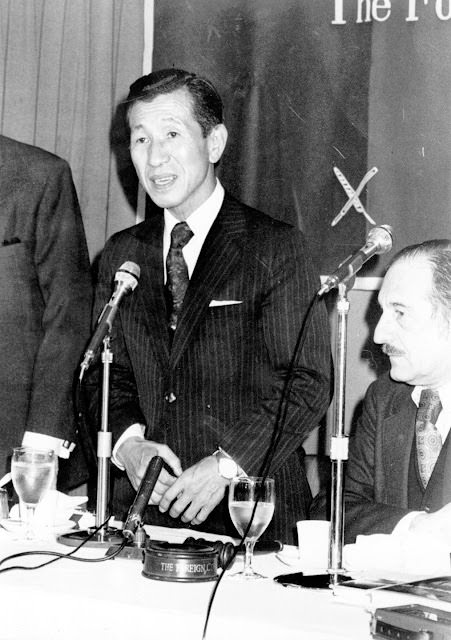

On March 9, 1974, in a very touching moment, Major Taniguchi told Onoda his mission was over, ending one of the longest times a soldier had ever kept fighting after a war. Onoda came out of the jungle in his old, worn-out uniform, into a world that had changed a lot from when he first went in.

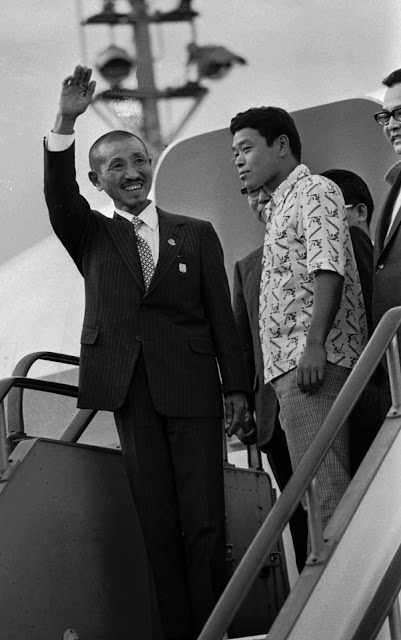

Hiroo Onoda’s return to Japan in 1974, after nearly three decades of isolation in the jungles of Lubang Island. He lived through the harrowing experiences of war and the subsequent years of survival under the belief that the conflict was ongoing, found himself in a society that was vastly different from the one he left behind. This drastic change in Japan’s social and cultural landscape profoundly impacted Onoda, stirring a deep concern for what he perceived as the erosion of traditional Japanese values in the face of rapid modernization and Western influence.

Disheartened by these observations, Onoda sought solace and purpose far from the land that had changed beyond his recognition. In April 1975, barely a year after his repatriation, he moved to Brazil to embark on a new venture—raising cattle. This interest was sparked during his time in hiding when he would listen to Australian cattle shows on a transistor radio he had acquired. Brazil offered Onoda a chance to start anew, away from the complexities and transformations of post-war Japan.

However, Onoda’s ties to Japan remained strong, and his concern for the country’s youth prompted his return in 1984. Troubled by a specific incident—a Japanese teenager’s murder of his parents in 1980—Onoda was motivated to contribute positively to the society he felt was veering away from its core values. He established an educational camp aimed at instilling discipline, respect, and a sense of purpose among the young. This camp was a manifestation of Onoda’s desire to reconnect Japan’s youth with the traditional values he feared were being lost in the country’s rapid post-war transformation.

Through this initiative, Onoda sought to provide a space where young people could learn about survival, responsibility, and the importance of nature, drawing on his unique experiences and the lessons he learned during his time in isolation. It was his way of giving back to his homeland, attempting to bridge the gap between generations and preserve the cultural heritage he so cherished.

He returned to Lubang Island in 1996 to donate $10,000 to local schools. Many think of him as part of their local history, and officials from the Philippines sent their condolences when he passed away in 2014 due to heart failure in Tokyo.