In the quiet corners of Victorian-era family albums lie some of the most hauntingly intriguing images from the history of photography. These are the “hidden mothers” photographs, where the desire to capture the perfect image of infancy led to a peculiar and somewhat spooky method of portraiture. Unlike the carefully curated, social media-worthy images of today, Victorian mothers (and sometimes fathers, nannies, or photographers’ assistants) went to great lengths to ensure their little ones were immortalized in stillness, often at the cost of their own visibility in the frame.

The technology of the time presented unique challenges. Early cameras required long exposure times to capture an image, often necessitating subjects to remain perfectly still for several minutes. Anyone who has tried to photograph children knows that asking them to freeze for even a moment is a tall order. Victorian parents were no different in their struggle, except their solution has left us with a fascinating photographic phenomenon.

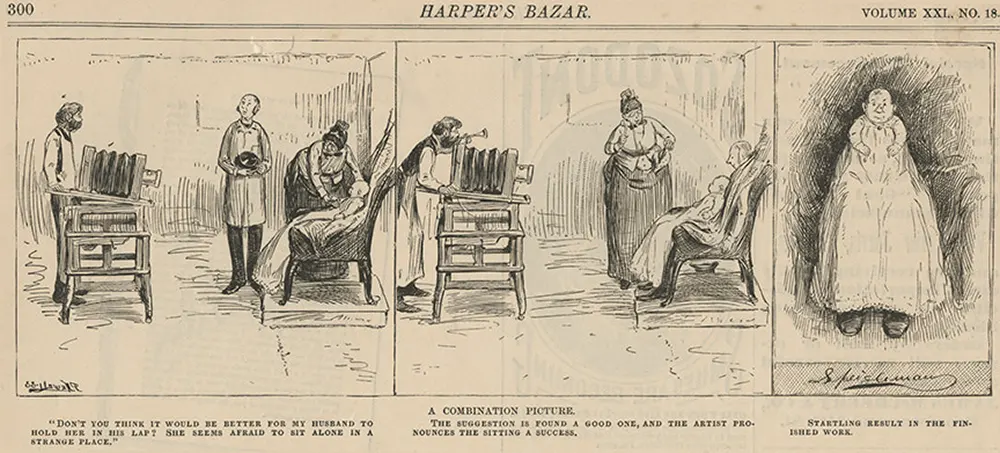

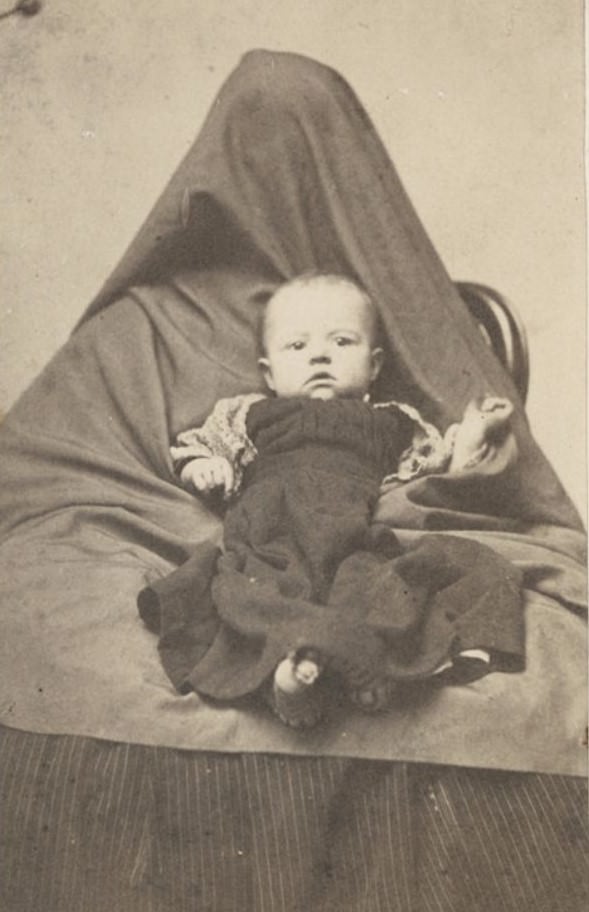

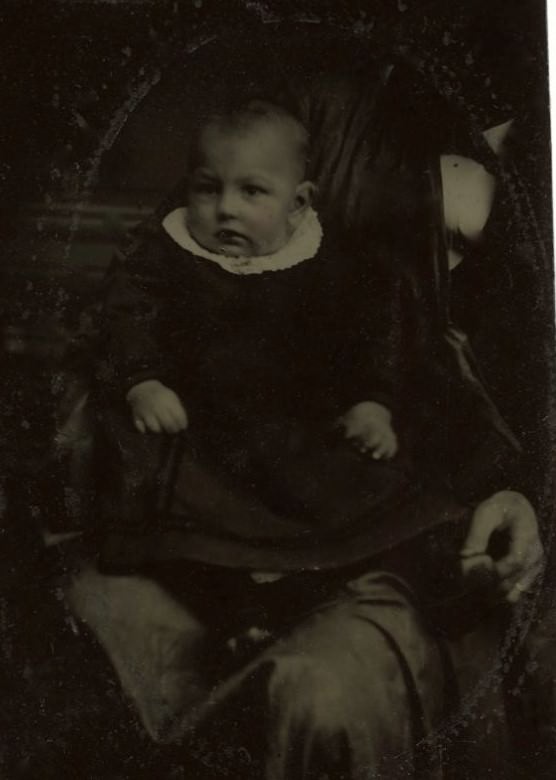

To achieve the desired effect of a serene, focused image of their child, parents often became part of the photography process in the most literal sense. They would hide within the frame, holding their children still, while remaining unseen themselves. This was achieved through various means: mothers might stand behind curtains, envelop themselves and their child under cloaks, or even disguise themselves as furniture, such as chairs or tables, upon which the child would sit.

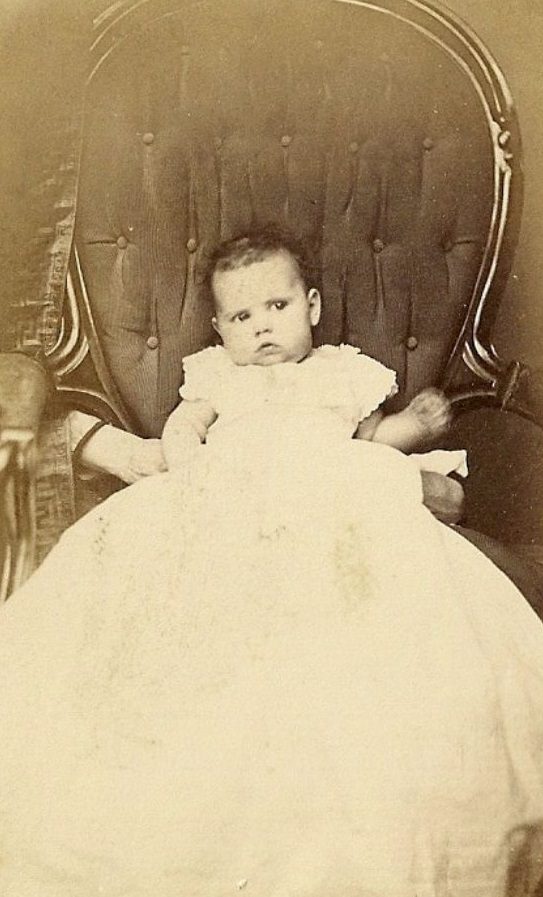

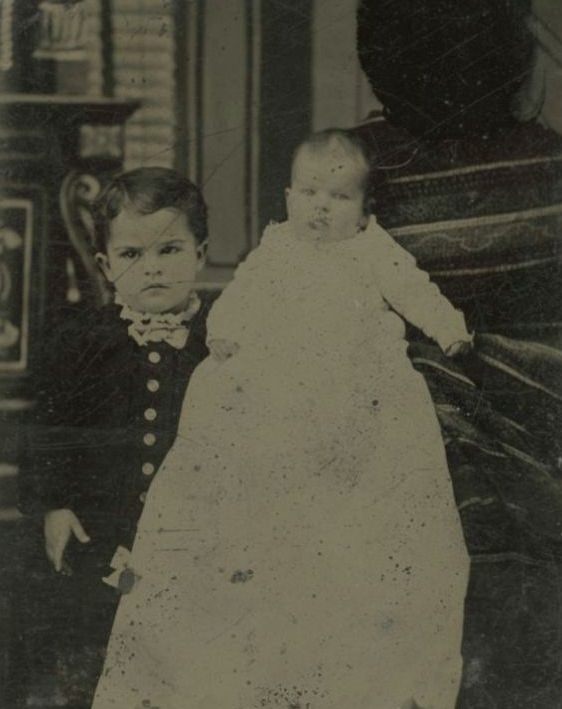

The effectiveness of these concealment efforts varied. In some instances, the mother’s shape, draped in fabric, was distinctly obvious, giving the impression of a ghostly presence lurking behind the child. In other photos, arms could be clearly seen, an eerie reminder of the living presence behind the still facade of the image.

For those instances where the mother’s presence was too apparent, photographers employed several techniques to keep the focus solely on the child. A common method was the use of a paper overlay when framing the photograph, effectively cropping out any part of the image that revealed the mother. In the darkroom, photographers might also choose to edit out the mother’s face, either by painting over it with black paint or by physically removing parts of the photograph. Alternatively, having the mother position herself just off to the side allowed for her to be cropped out of the image during the final stages of production.

This genre of photography, known as “hidden mother photography,” was not merely a technical workaround but became a prominent and hauntingly beautiful genre during the early stages of photography. The necessity-driven creativity of these early photographers and the families they photographed has left us with a body of work that is as unsettling as it is captivating.