In World War I, the Hellfighters, an infantry regiment of the New York Army National Guard, were the most celebrated African American unit. They were nicknamed the Black Rattlers. Frenchmen nicknamed the regiment Men of Bronze (French: Hommes de Bronze), and Germans gave it the name Hell-fighters (German: Höllenkämpfer). These African American troops fought a war for a country that denied them fundamental rights, just like their predecessors in the Civil War and their successors in the wars that followed – and their bravery stood as a rebuke to racism.

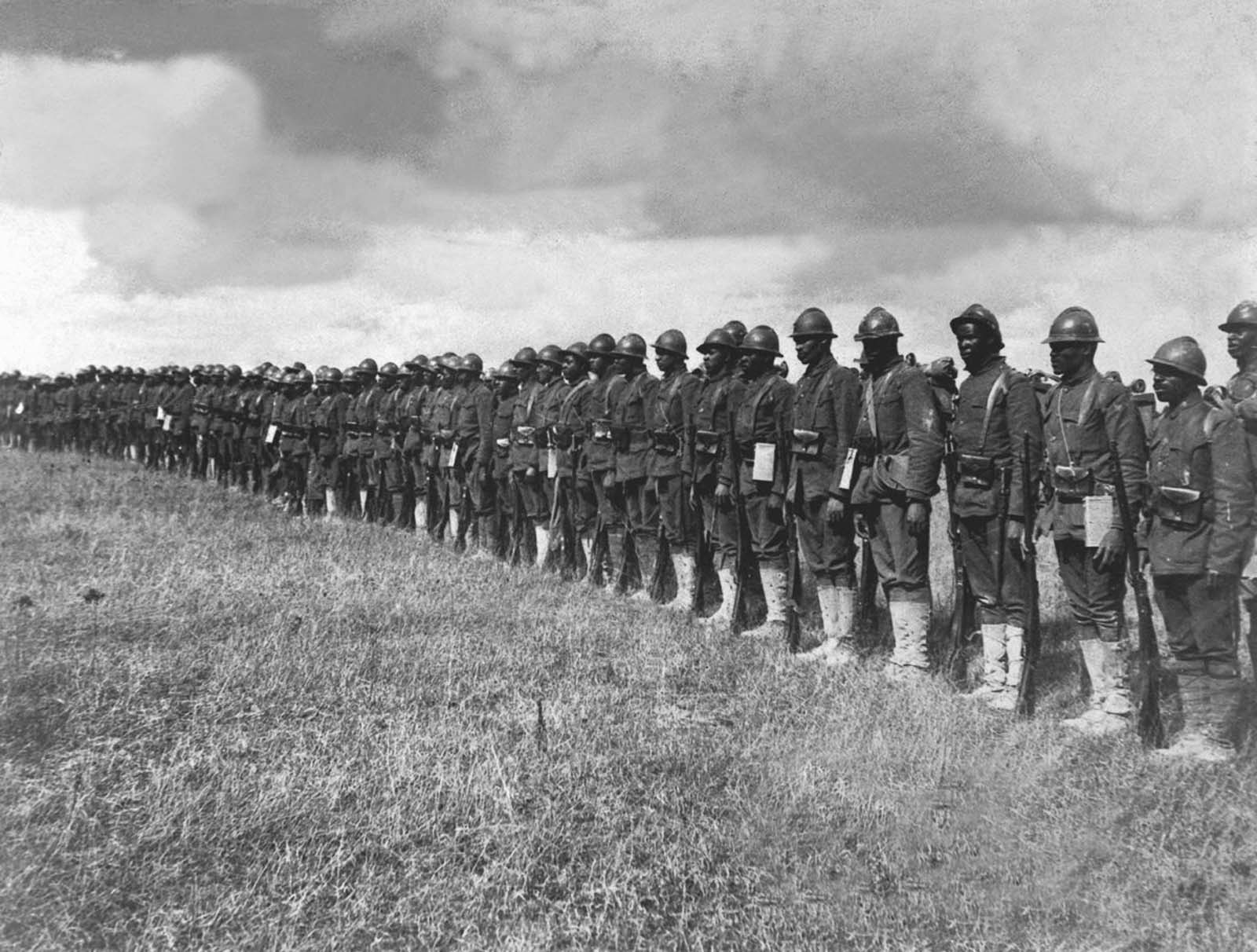

In 1910, 50,000 of Manhattan’s 60,000 African Americans lived in Harlem, home to most enlistees. Other immigrants came from Brooklyn, towns up the Hudson River, and New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. Many African Americans believed that joining the armed forces would help eliminate racial discrimination in the United States when the U.S. entered World War I. By serving in the armed forces, they could prove to their white counterparts that they deserved respect. Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina, was where the Regiment received combat training in October 1917. The camp was set up like the French battlefields. During their time at Camp Wadsworth, they experienced significant racism from the local community and other units. At the end of 1917, the 369th shipped out, and when it arrived in France, it joined its brigade. Instead of combat training, the unit was relegated to labor service duties. Due to a widespread refusal by white American soldiers to perform combat duty with black soldiers, the U.S. Army decided to assign the unit to the French Army in April 1918. Despite wearing their U.S. uniforms, the men received French weapons, helmets, belts, and pouches.

The “Harlem Hellfighters” rapidly gained a reputation for their courage and effectiveness. The Hellfighters saw government propaganda directed at them overseas. According to the article, Germans had done nothing wrong to blacks, and they should be fighting the U.S., which had oppressed them for decades. It had the opposite effect of what was intended. In conjunction with the American drive in the Meuse-Argonne, the French 4th Army went on the offensive on 25 September 1918. Despite suffering severe losses, the 369th performed well during heavy fighting. The unit captured the vital village of Séchault. In total, the 369th spent 191 days in frontline trenches, more than any other American unit. They also suffered the most casualties of any American regiment, with 1,500.

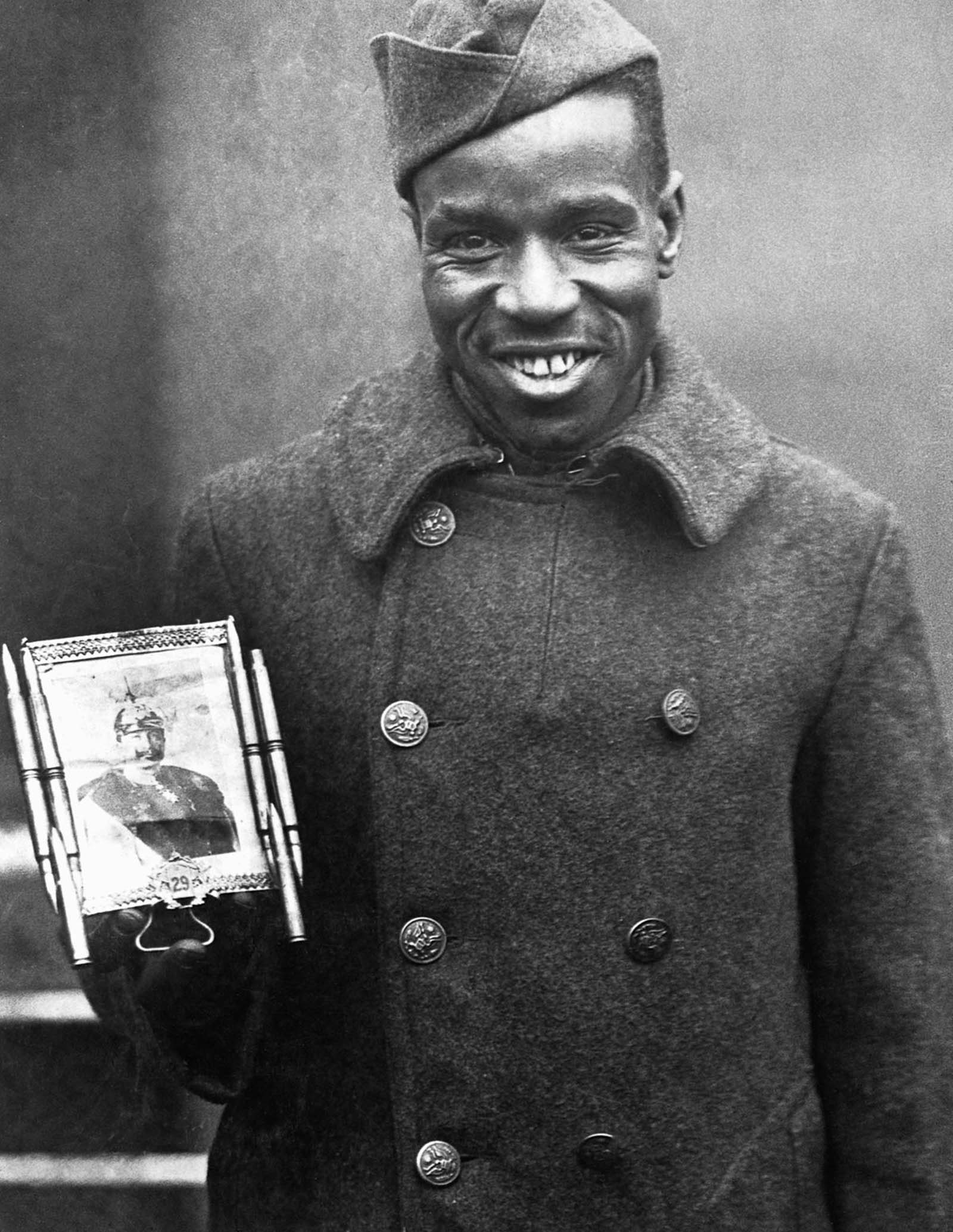

After Armistice Day, one month after 13 December 1918, the French government recommended the French Croix de Guerre for 170 individual 369th members, and the Regiment was also recommended for a unit citation. General Labor pinned it to the unit’s colors. Not only was the 369th Regiment “Hellfighters Band” used in battle, but also for morale. By the end of their tour, they had become one of Europe’s most famous military bands. The 369th followed them overseas and were known for boosting morale instantly. Overseas, the 369th Regiment constituted less than 1% of the soldiers but was responsible for over 20% of all land that belonged to the United States. The 369th returned to New York City at the end of the war, and on 17 February 1919, they marched through the city. For all of Harlem, it became an unofficial holiday of sorts. Black school children were dismissed from class to attend the parade.