In 1843, Robert Adamson, a Scottish chemist, and David Octavius Hill, a painter, formed a pioneering photographic studio in Edinburgh. This partnership came about only four years after the invention of photography. Their studio, known as Hill & Adamson, was situated at the foot of Calton Hill. Together, they produced hundreds of photographs, capturing portraits, landscapes, and social scenes.

Robert Adamson was born on April 26, 1821. He was known for his keen interest in chemistry, which eventually led him to photography. At that time, photography was a new and exciting field. The technique they used was called the calotype process. This method involved creating a paper negative from which multiple positive prints could be made. The calotype process was different from the daguerreotype, another early photographic method, which produced a single, unique image on a silvered copper plate.

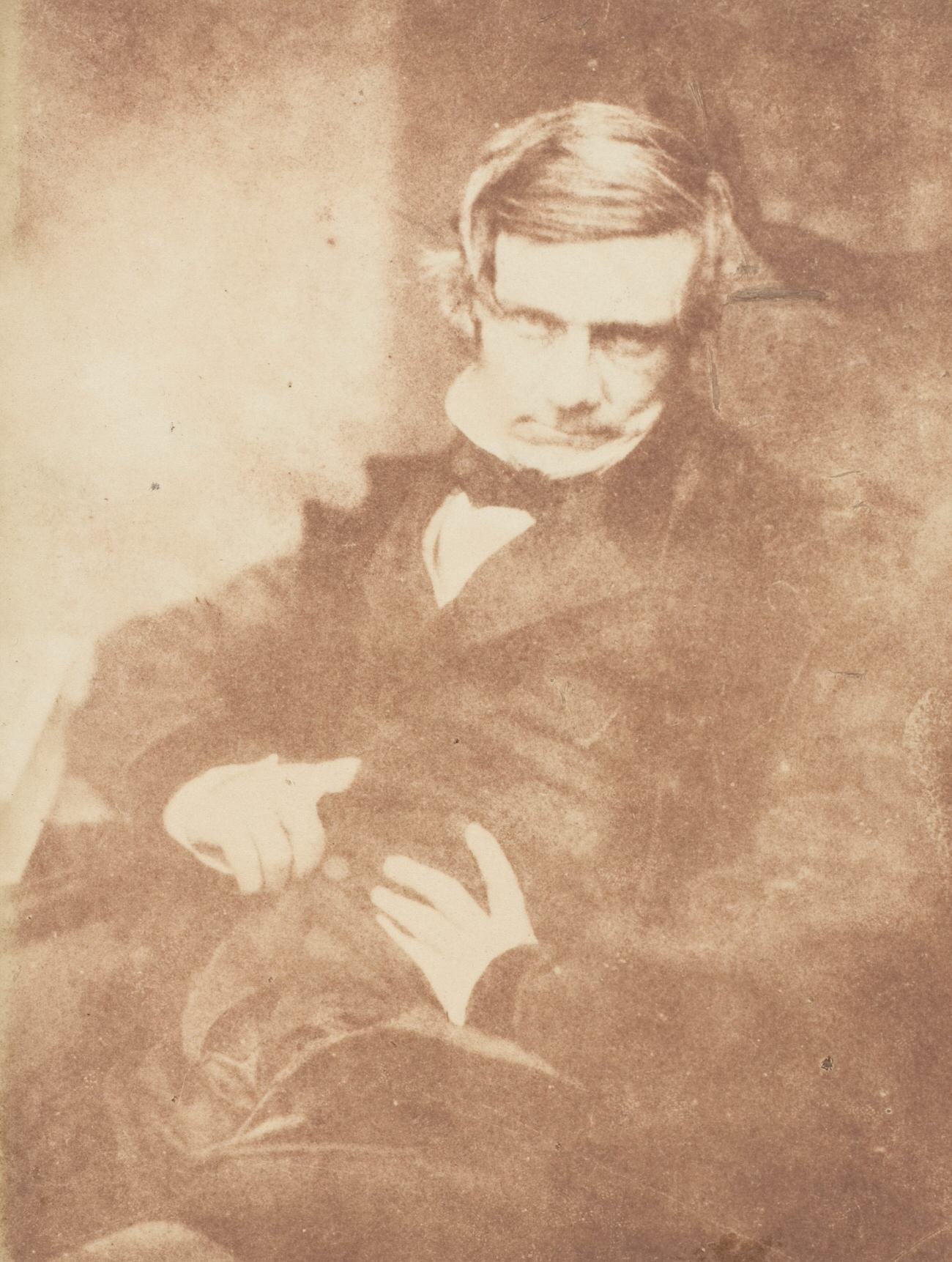

Adamson’s partner, David Octavius Hill, was born on May 20, 1802. Hill was already an established painter by the time he teamed up with Adamson. He had a great eye for composition and detail, which complemented Adamson’s technical expertise. Together, they were able to create photographs that were both artistic and technically advanced.

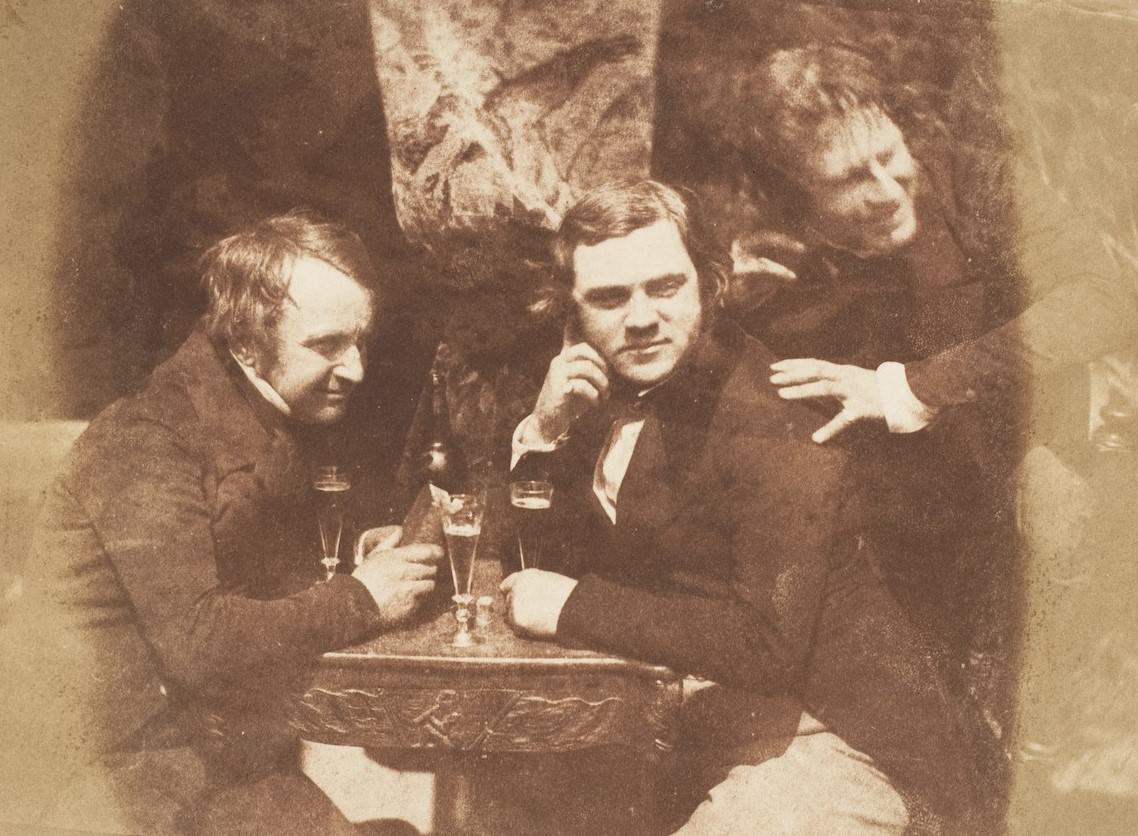

One of their most notable photographs is the first known image of people enjoying a drink in an Edinburgh pub, taken in 1843. This photograph is remarkable because it captures a candid moment in the everyday life of the people at that time. The image shows a group of men gathered around a table, enjoying each other’s company and drinks. This photograph is not just a simple snapshot; it is a window into the past, showing us how people lived and interacted over 181 years ago.

Read more

The calotype process that Adamson and Hill used required a lot of sunlight. Because of this, many of their photographs were taken outdoors, even if the subjects were meant to look like they were indoors. Hill designed their garden to resemble an interior space, complete with furniture and props, so they could create the illusion of an indoor setting while taking advantage of the natural light.

Creating a calotype involved several steps. First, a sheet of high-quality writing paper was coated with silver nitrate and then dried. Next, it was dipped in a solution of potassium iodide to form silver iodide. After that, the paper was sensitized with a mixture of silver nitrate and gallic acid. This made the paper sensitive to light. The sensitized paper was then placed in the camera, and the exposure was made. This could take anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes, depending on the lighting conditions. After the exposure, the paper was developed in a solution of gallic acid and silver nitrate, which brought out the image. Finally, the negative was fixed with a solution of sodium thiosulfate to make it permanent.

Adamson and Hill’s photographs were unique because they combined the technical aspects of photography with the artistic elements of painting. Hill’s background as a painter influenced the way they composed their images. He paid close attention to the arrangement of the subjects, the use of light and shadow, and the overall mood of the photograph. Adamson’s understanding of chemistry and the photographic process ensured that the images were clear and well-exposed.

In addition to the famous photograph of people enjoying a drink in the pub, Adamson and Hill produced many other notable portraits. They photographed a wide range of subjects, from well-known figures of the time to ordinary people. Their portraits often had a sense of depth and character that was not common in early photography.

Adamson and Hill’s work extended beyond portraiture. They also took photographs of landscapes and architectural scenes. These images often had a sense of grandeur and majesty, capturing the beauty of the Scottish countryside and the intricate details of its buildings. One notable example is their photograph of the Scott Monument in Edinburgh. This image shows the monument in all its Gothic splendor, with its intricate carvings and towering spires.

Despite the challenges of working with the calotype process, Adamson and Hill’s photographs were of exceptional quality. Their images were sharp and clear, with a rich tonal range that brought out the details of the subjects. This was due in part to Adamson’s skill in handling the chemical processes involved in creating the calotypes. His expertise ensured that the images were properly exposed and developed, resulting in photographs that were both technically proficient and artistically compelling.

Unfortunately, Robert Adamson’s career was cut short by his untimely death in 1848, just five years after he began working with Hill. Despite his brief career, Adamson made a significant impact on the field of photography. His collaboration with Hill produced some of the earliest examples of photographic art, setting a high standard for future photographers.

David Octavius Hill continued to work as a painter after Adamson’s death, but his partnership with Adamson remained a defining period in his career. The photographs they created together are still celebrated today for their artistic and historical significance. These images provide a glimpse into the lives of the people and the landscapes of 19th-century Scotland, preserving moments in time for future generations to appreciate.