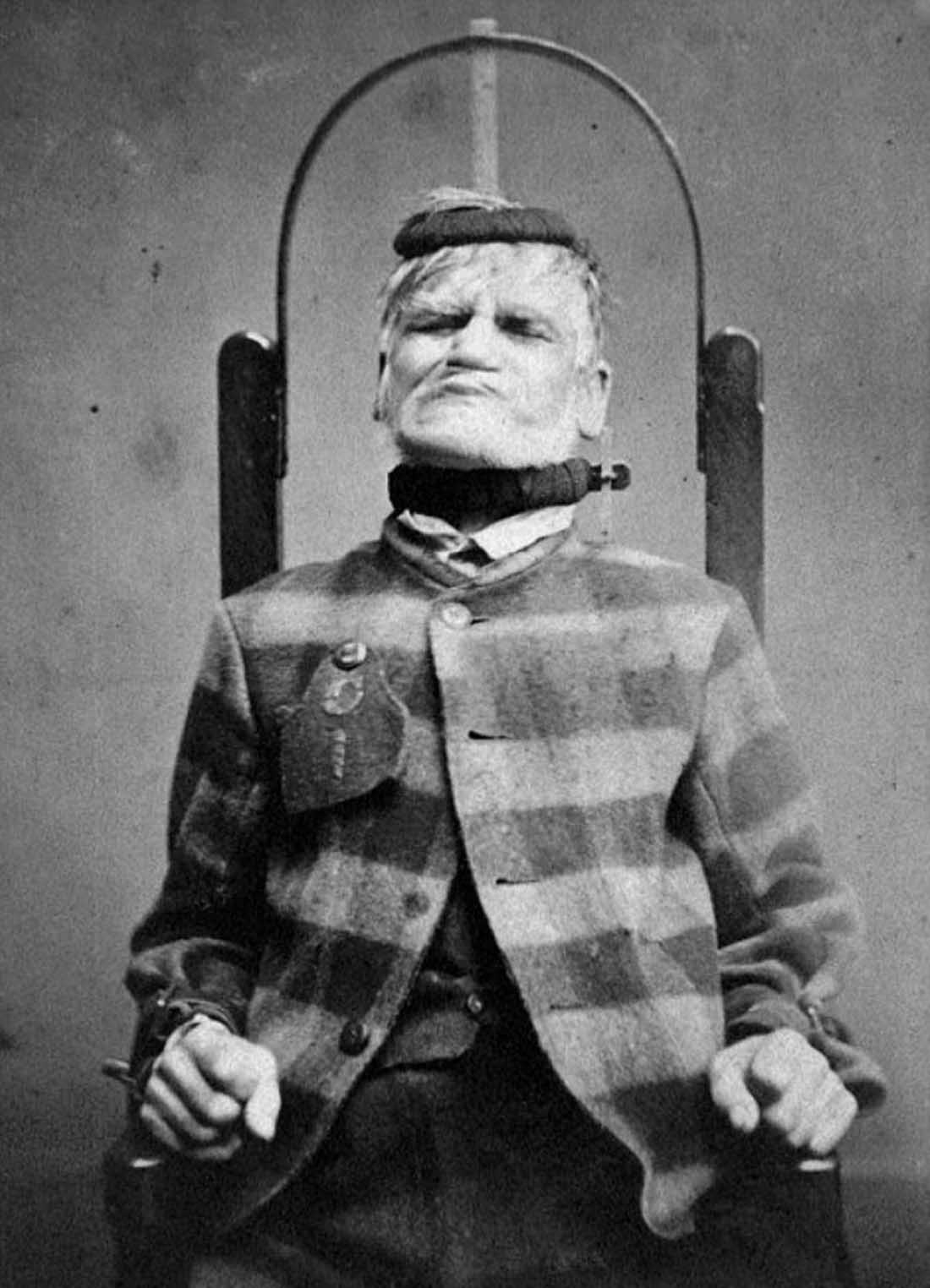

During the Victorian era, there were not many asylum built, but the number of patients in them grew by leaps and bounds. It is unclear whether this increase was primarily the result of increased psychotic illness or a decrease in community tolerance of the mentally ill. Most patients were admitted under the Poor Law and Lunacy Acts. Mentally ill people were treated under the Lunacy Act of 1845, explicitly changing their status to patients who required services. Counties were legally required to provide asylum for people with mental disabilities under the act. A qualified physician must be a resident in every asylum with a written regulation. Mental asylums were historically equivalent to psychiatric hospitals. The word asylum comes from religious asylums, which provided refuge to those with mental illness. In the past, almost all care for people with mental illness or learning disabilities was provided by their families.

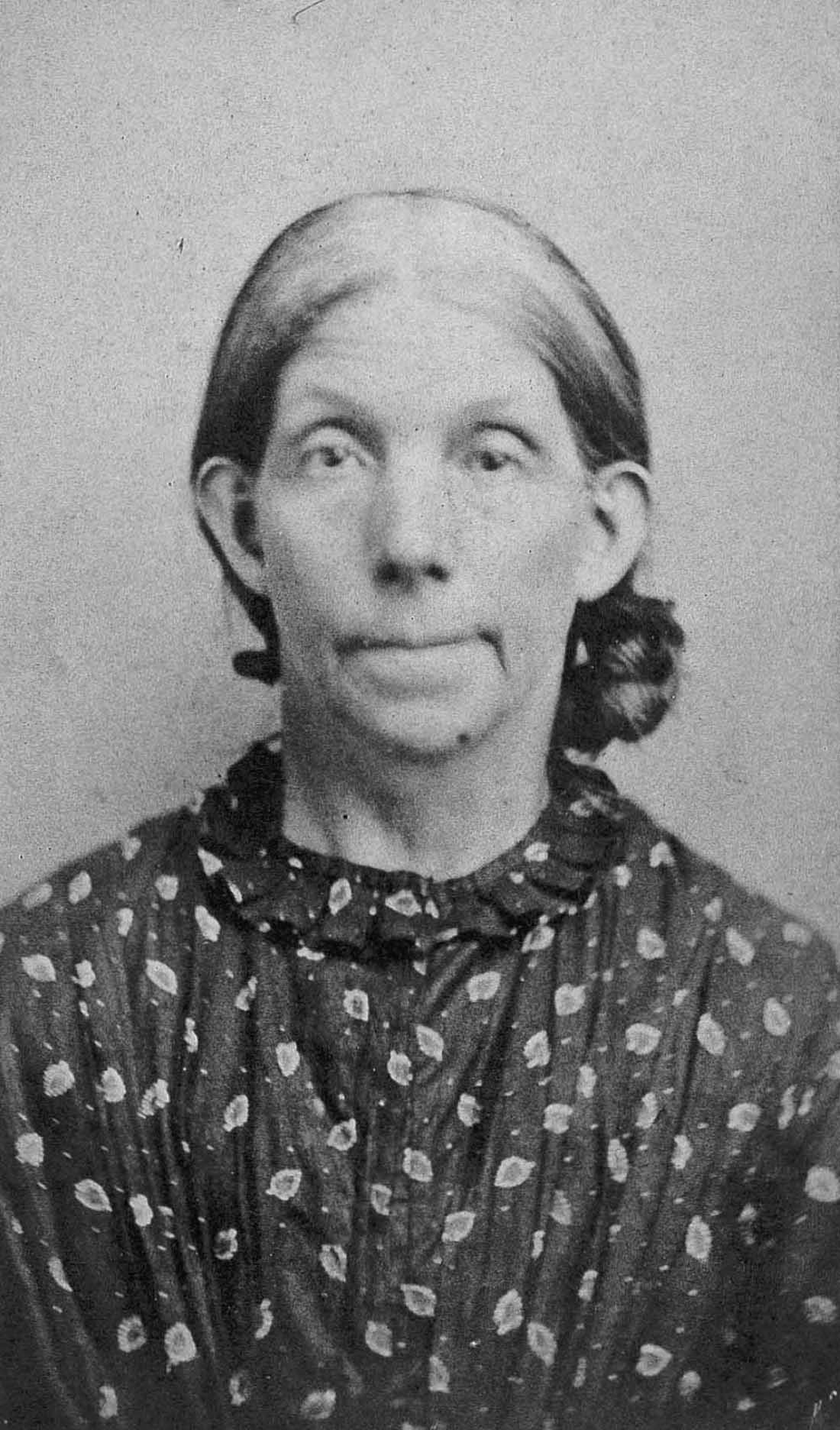

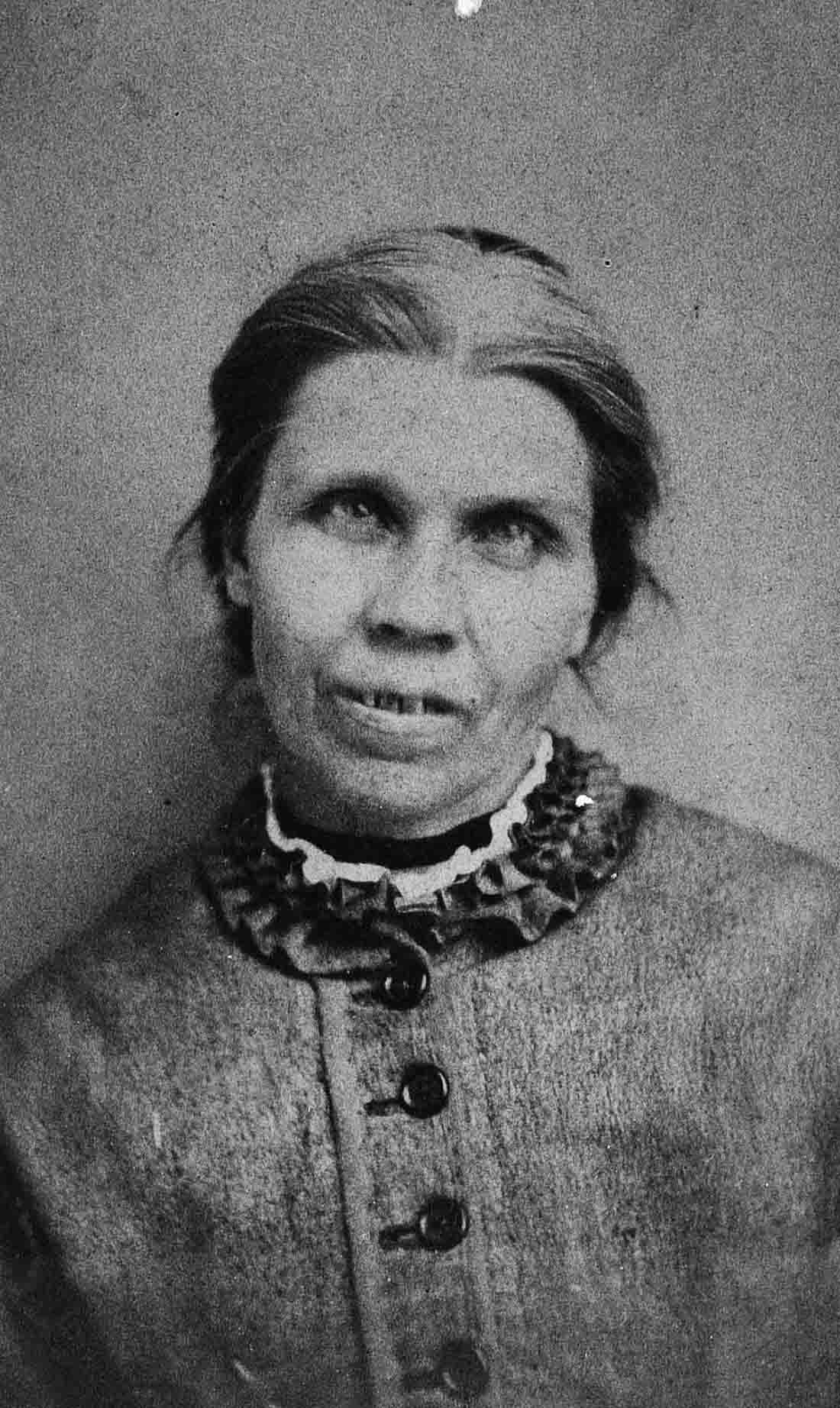

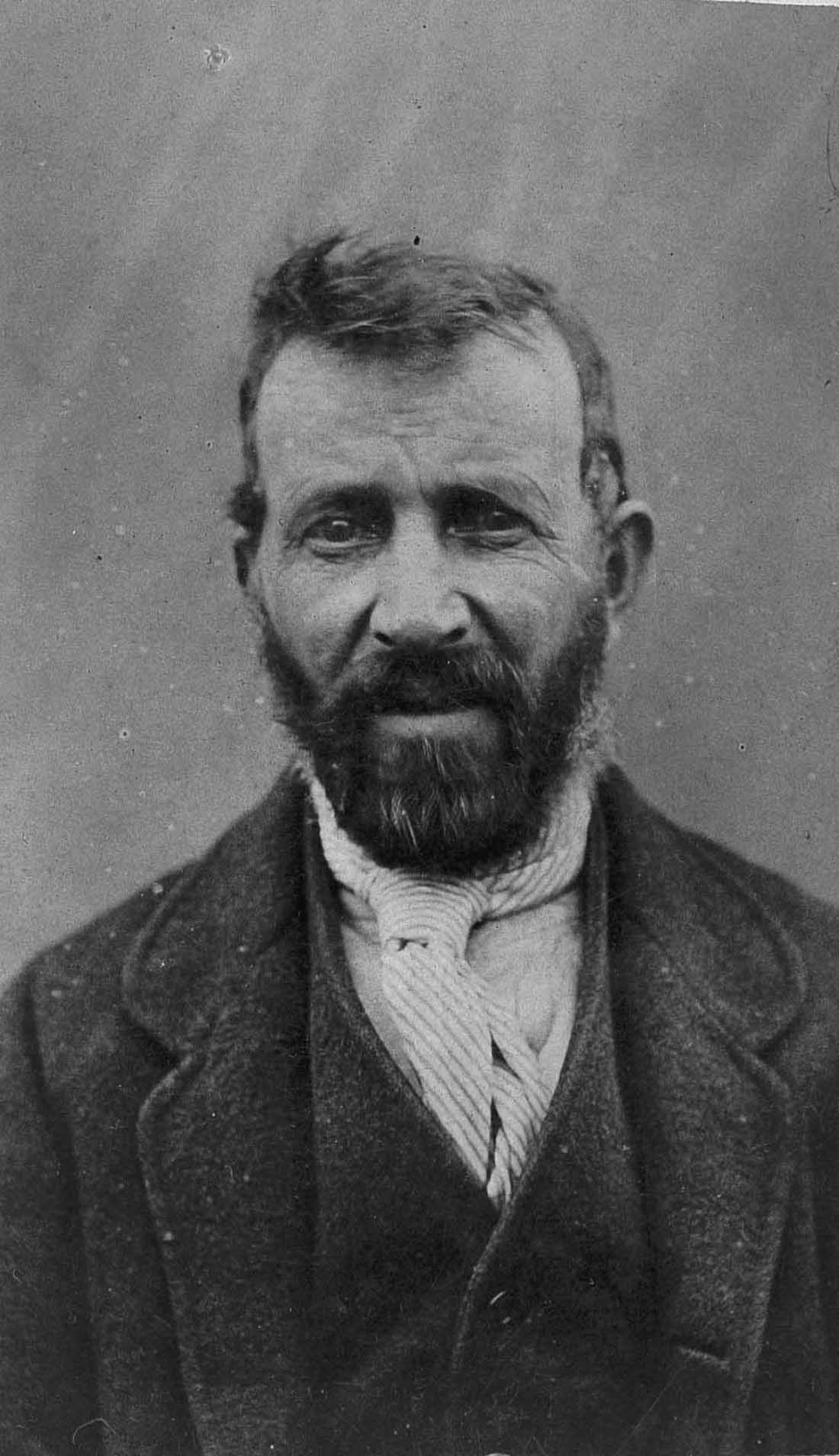

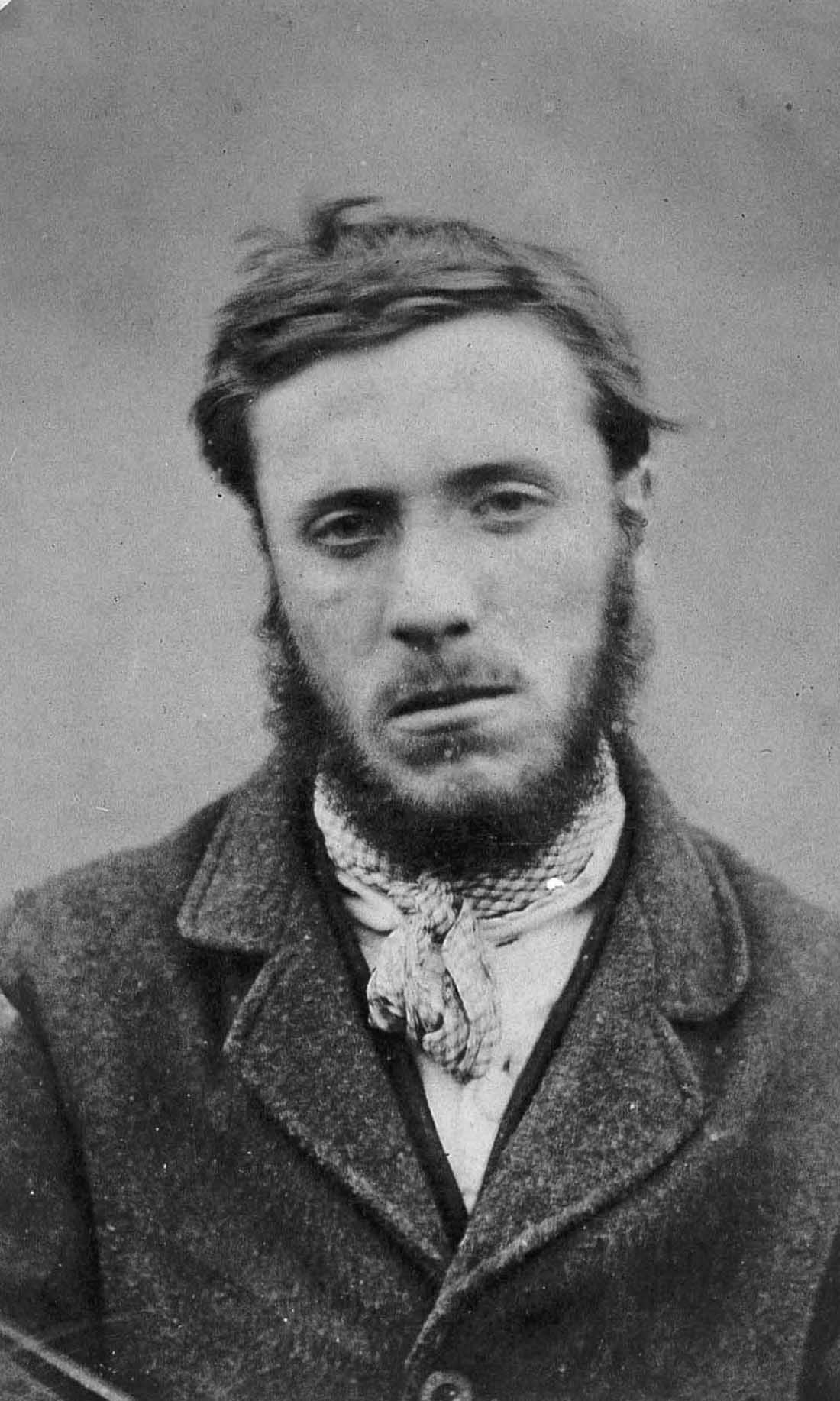

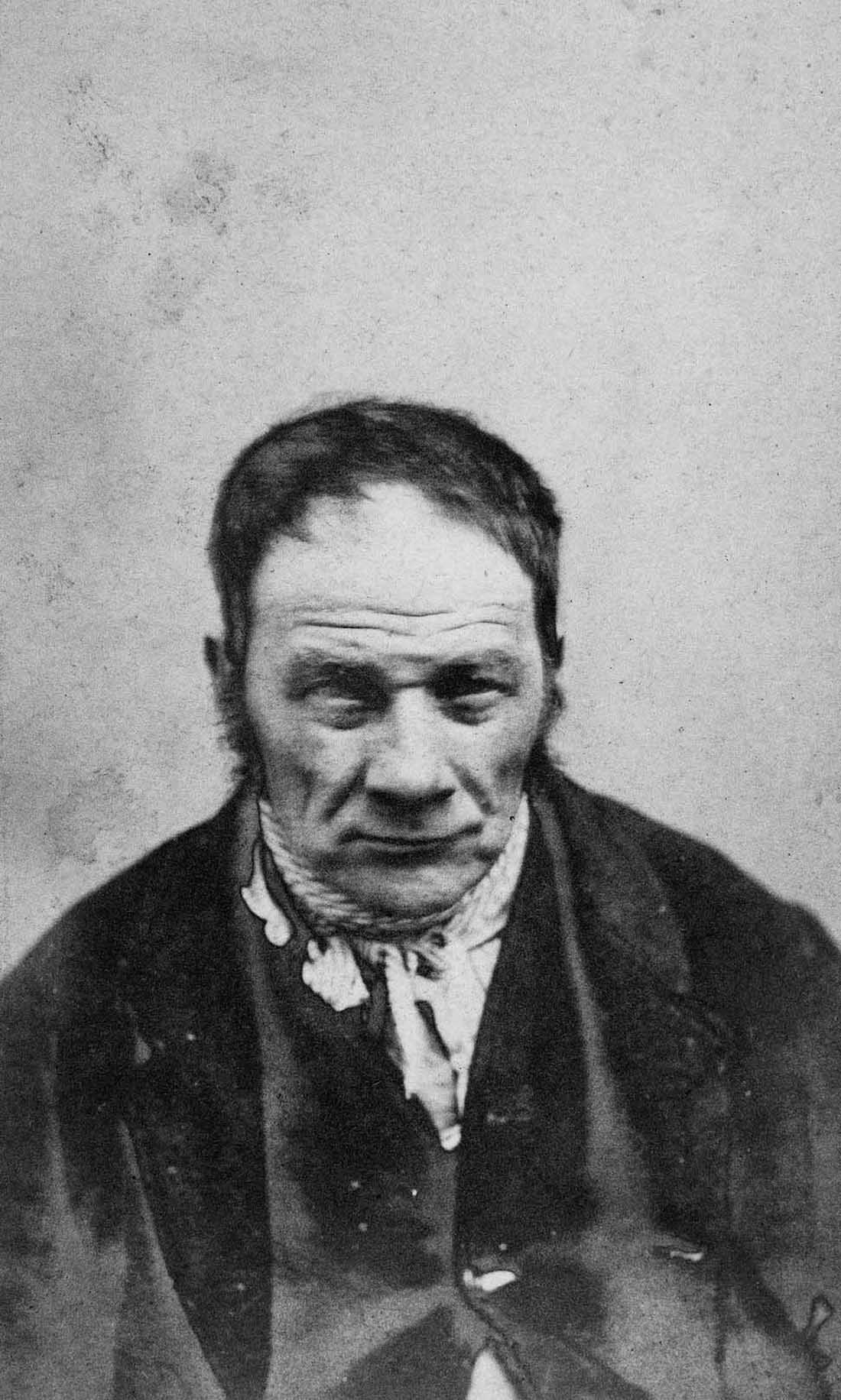

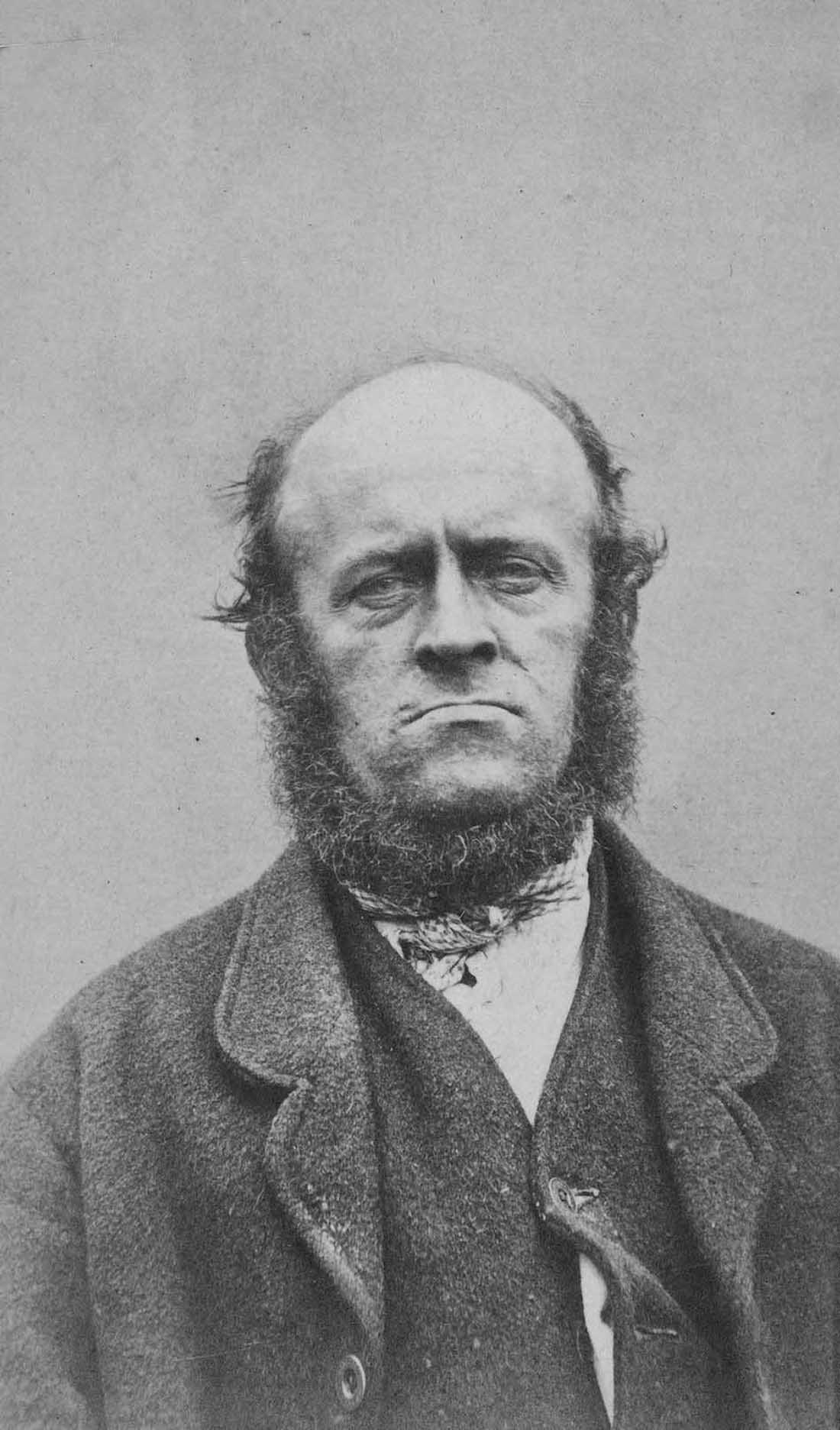

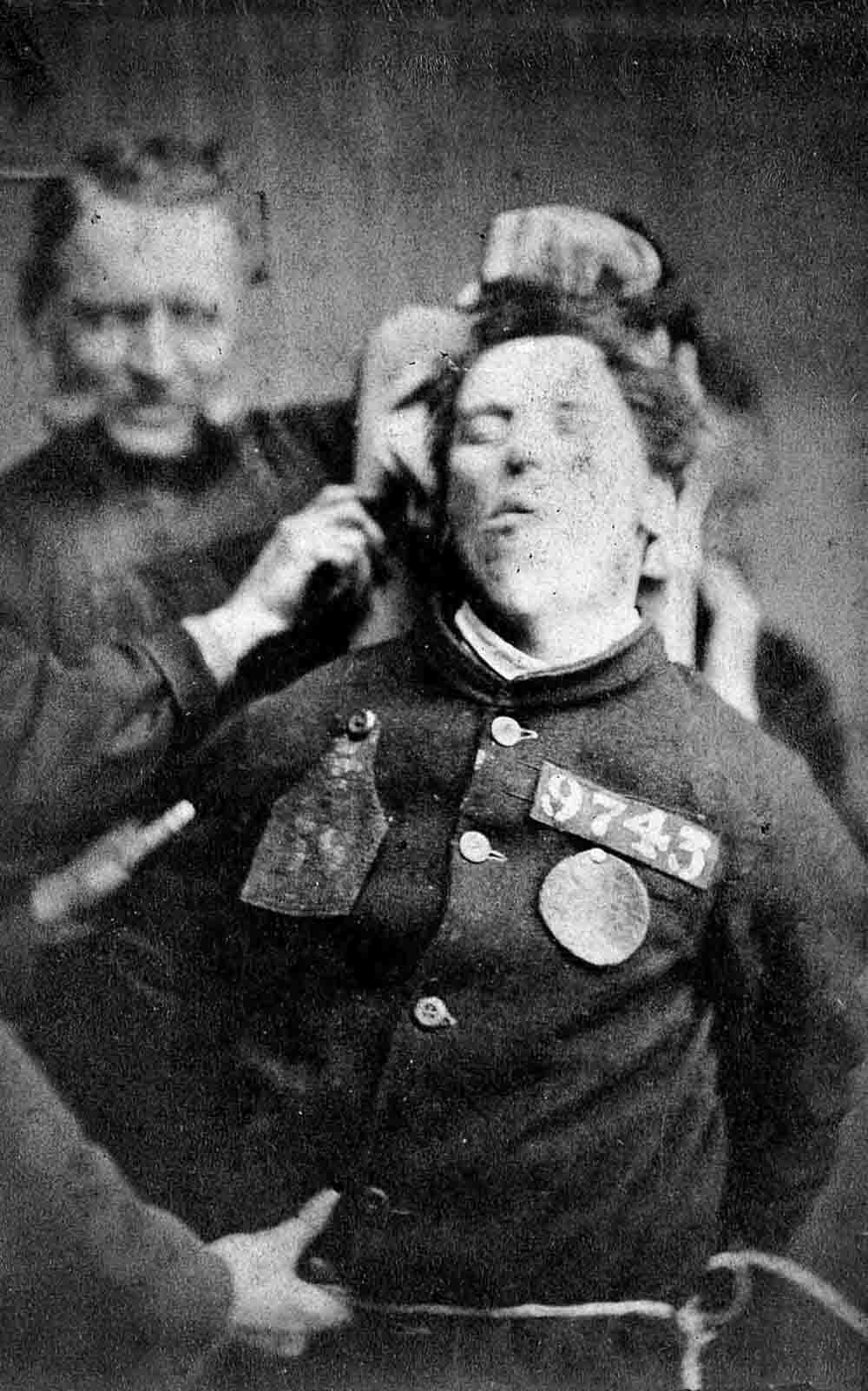

At the asylums of the 1860s, patients had to provide detailed information about themselves before being admitted. Among the details needed were: name of the patient; sex and age; married or single; previous occupation; religious affiliation; age at the time of the first attack; duration of existing attack; supposed cause; whether epilepsy was present; and whether the patient was suicidal or dangerous.

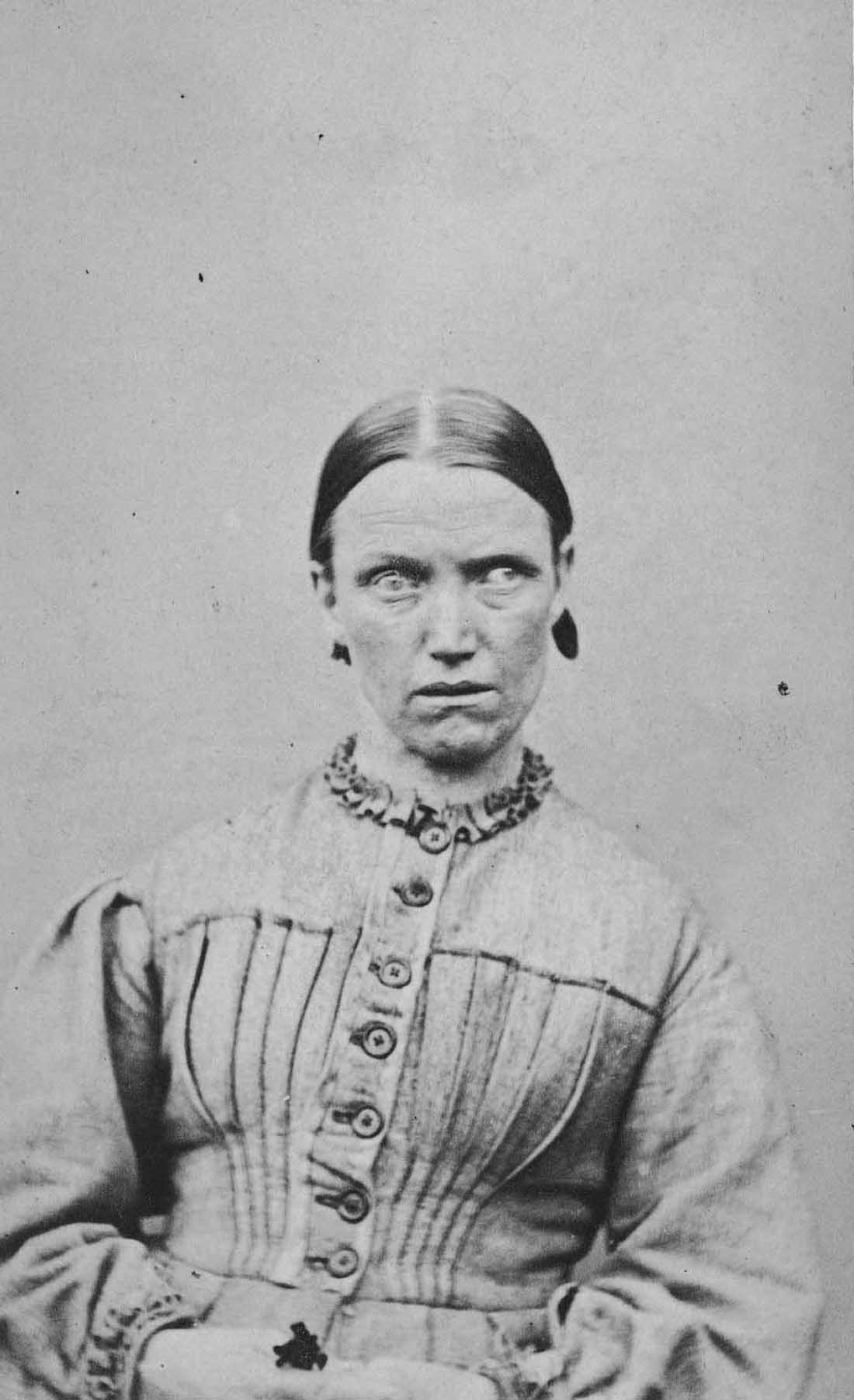

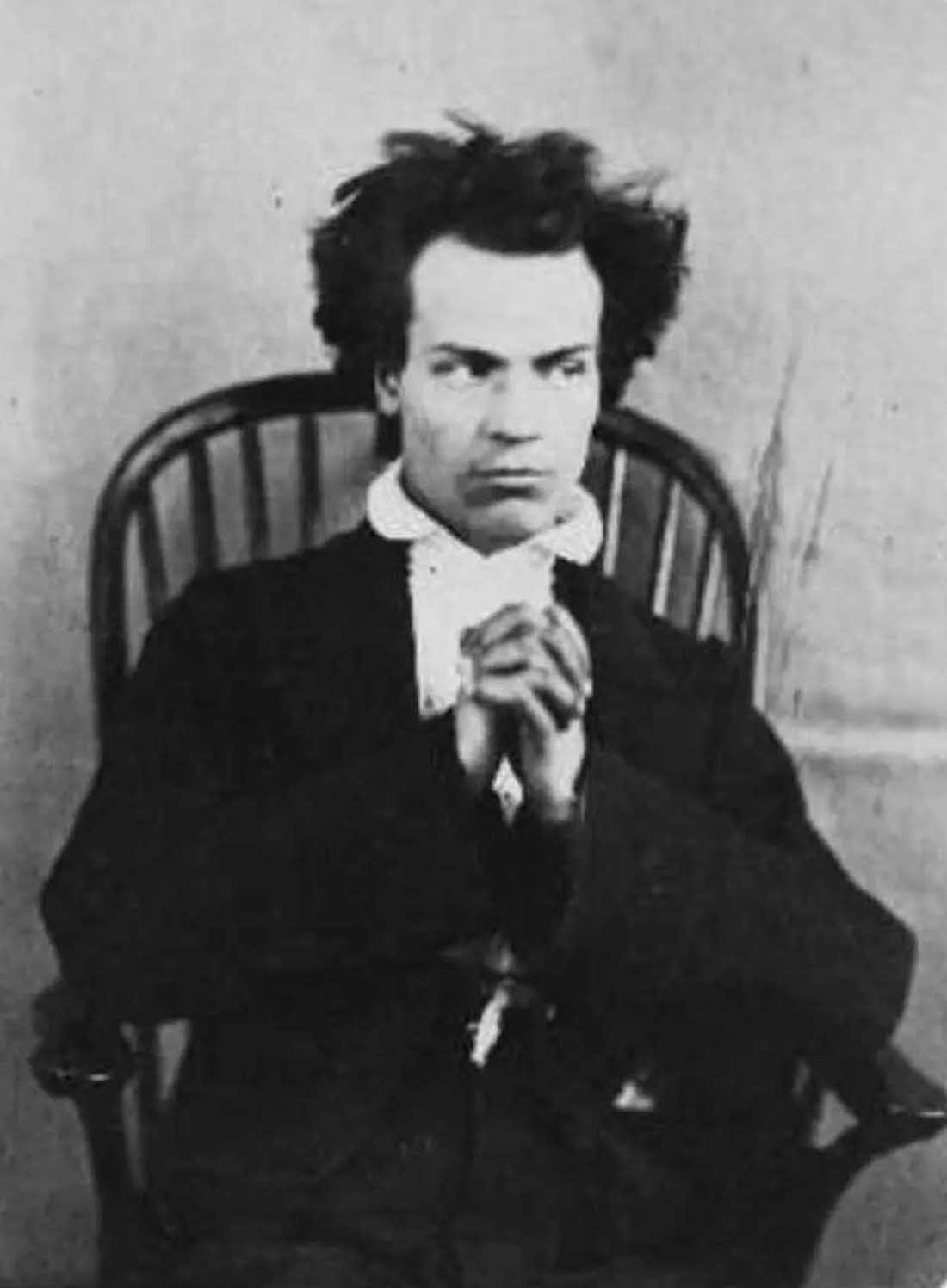

Detention was not appealable once the patient had been admitted. However, a relative or friend could apply to discharge a patient, as long as they confirm that they will take proper care of them and prevent them from injuring themselves or others. Even with the good intentions of the 1853 Act, it seems there was still plenty of scope for abuse. Many people considered asylums to be prisons disguised as hospitals. People with money often used private madhouses as dumping grounds for unwanted wives as a convenient way to remove the poor and incurable from society. Even though many patients were admitted for short periods, there are plenty of stories of people admitted to asylums, often for unsatisfactory reasons, and then basically ignored. Unfortunately, some patients died without being released after spending twenty years or more locked away. Almost all admissions decisions seemed to be based on personal judgment and were heavily biased against women. Women were often incarcerated in these institutions in more significant numbers than men.