In the pantheon of artists, Claude Monet often emerges as one of the most beloved and renowned, his name synonymous with Impressionism’s charm and elegance. However, beyond the canvas, Monet cultivated a different kind of masterpiece during the later years of his life – his enchanting home, studio, and gardens in Giverny, a small village nestled in Normandy, France. Between 1900 and the 1920s, this sanctuary not only influenced Monet’s art but also became a vibrant, living palette that the artist would tirelessly modify and refine.

The Giverny Estate: More Than a Home

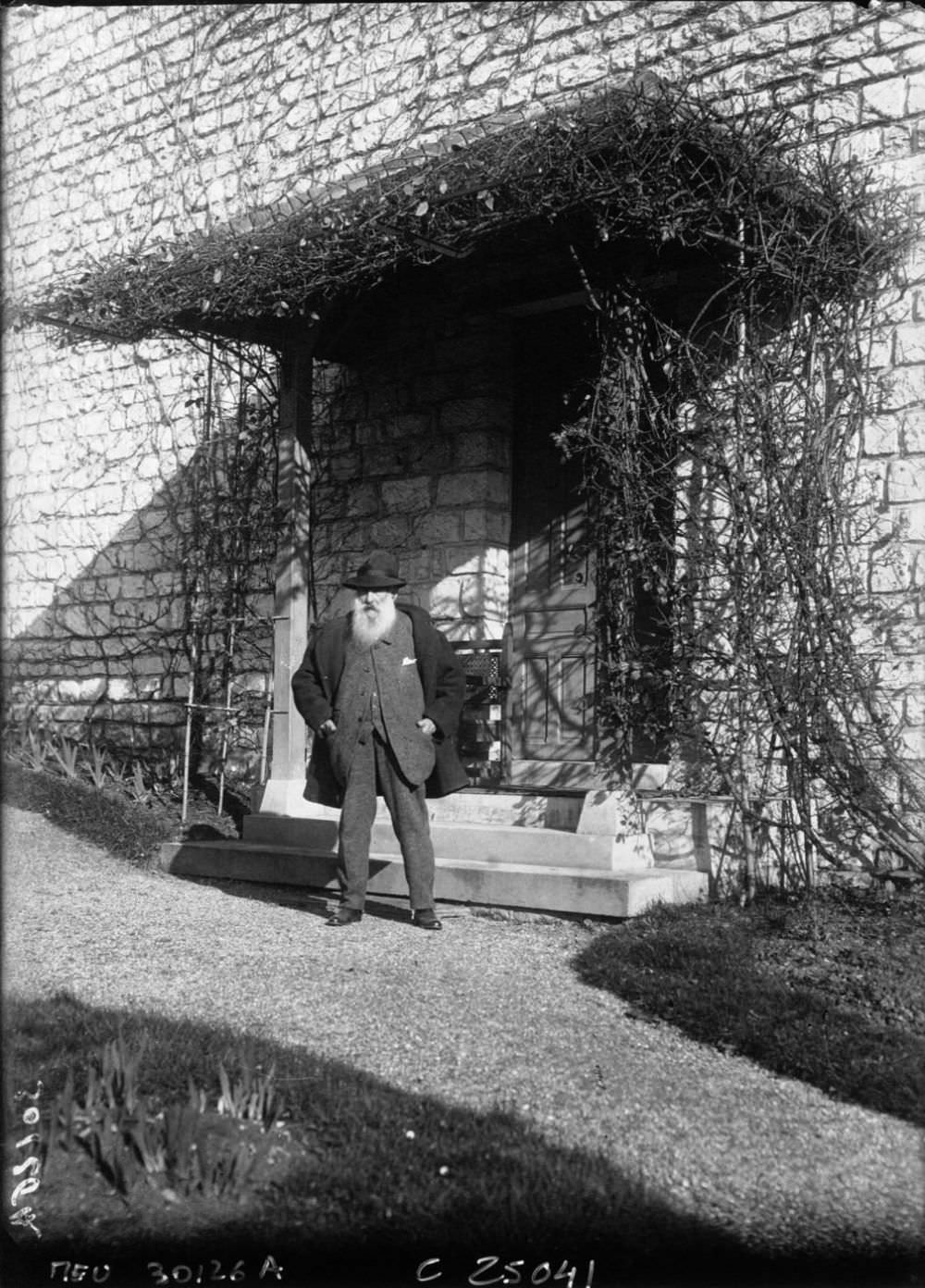

After achieving financial success, Monet purchased the Giverny estate in 1890. What would follow was not just the establishment of a residence but the meticulous creation of an environment that would fuel his art for over three decades. Monet was not a mere resident of Giverny; he was its architect, infusing his aesthetic sensibilities into the property’s very essence.

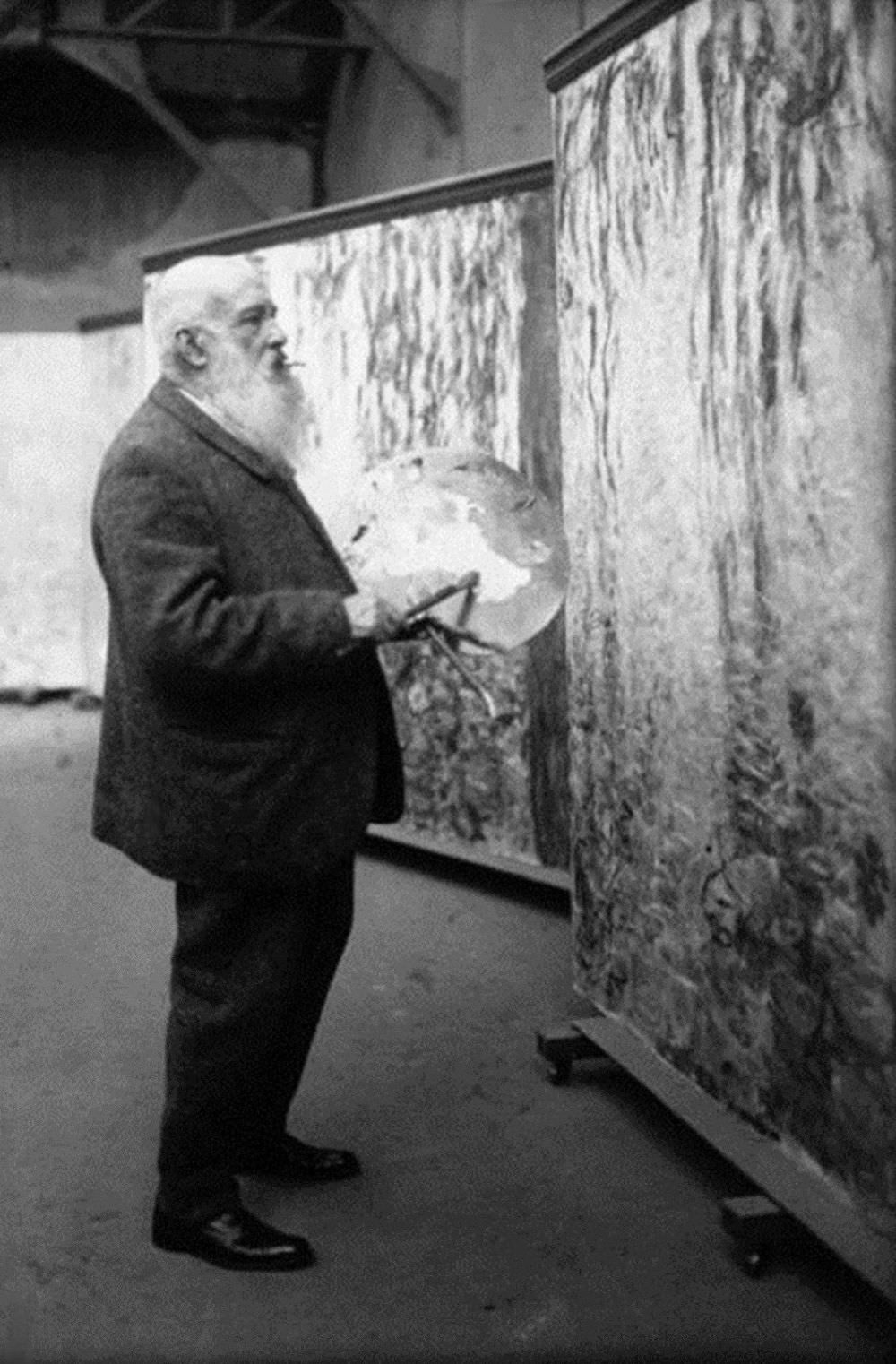

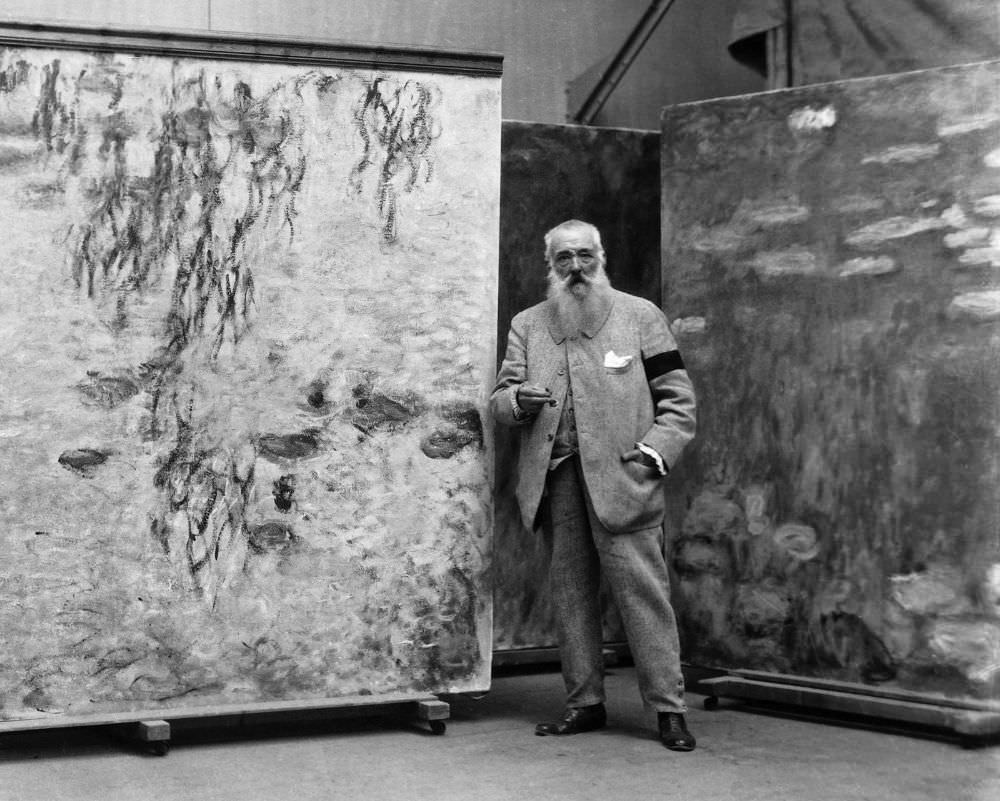

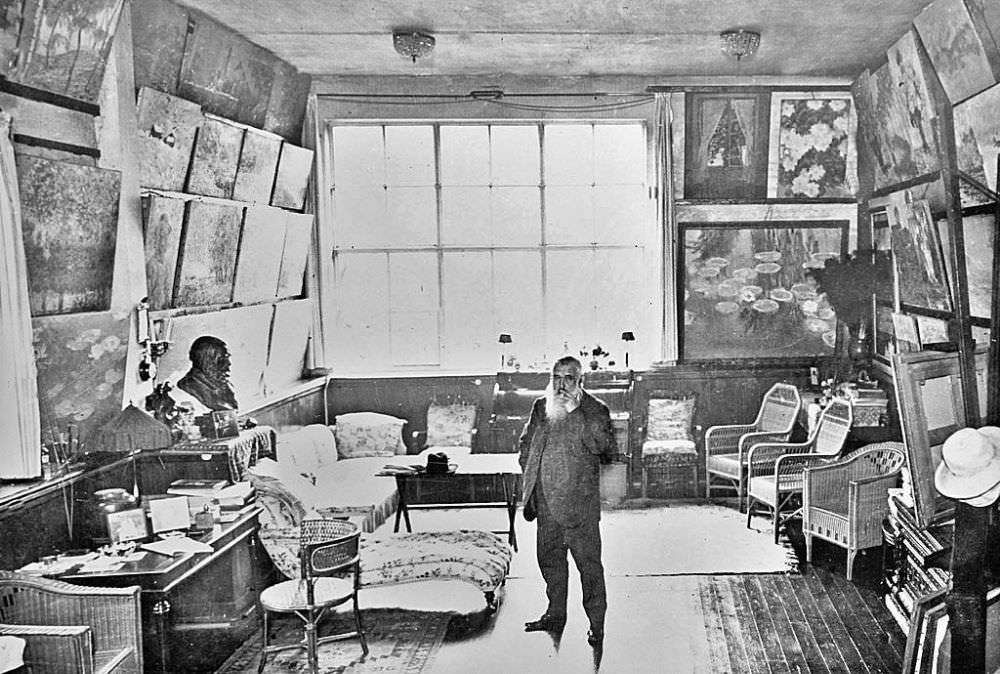

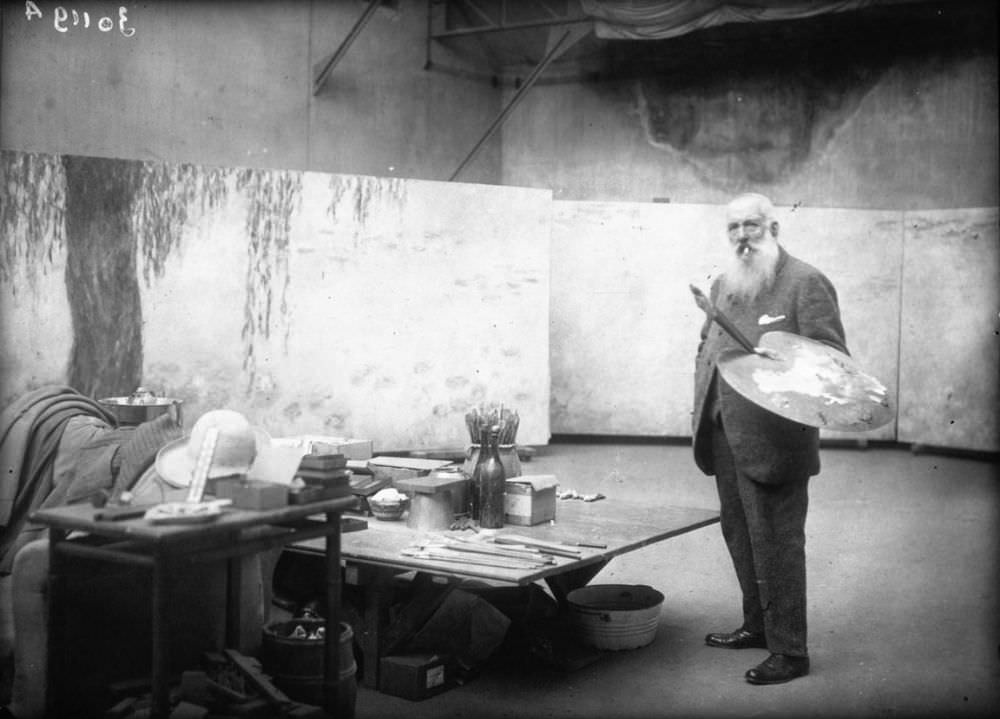

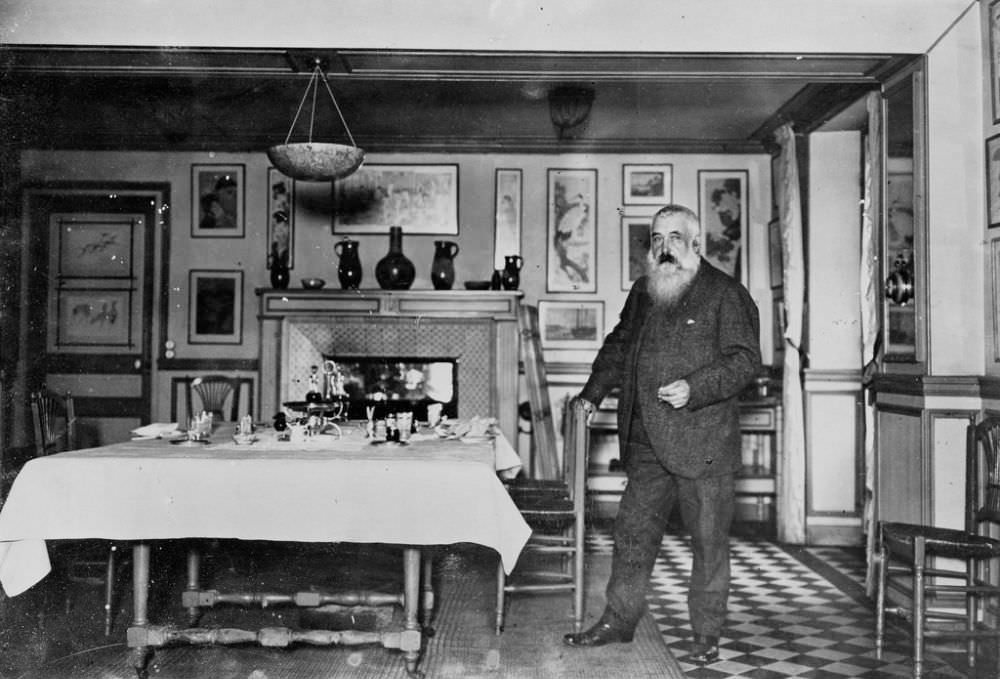

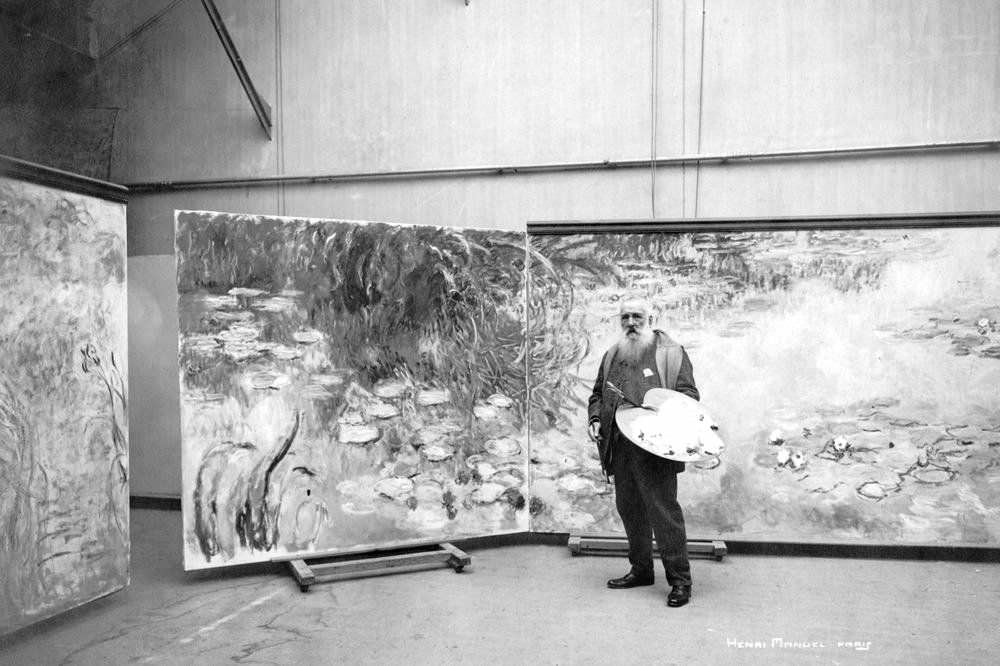

The pink-plastered main house, with green shutters, was more than Monet’s living quarters; it was a place for contemplation and familial life. The artist’s own studio, a large, well-lit room, was deliberately situated within this domestic haven. Here, in this dedicated space filled with paints, brushes, and canvases, Monet translated his surrounding environment’s beauty onto canvas, an environment he had purposefully designed.

The Clos Normand and Water Garden: A Living Canvas

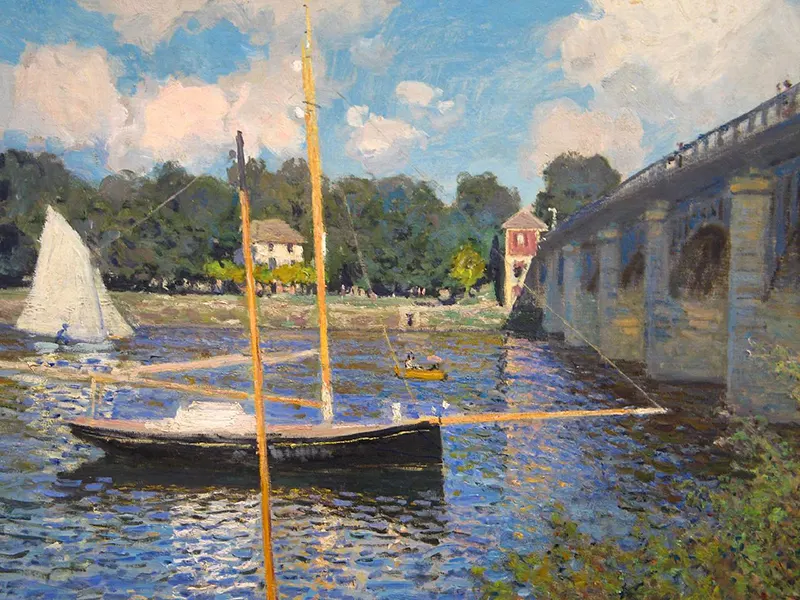

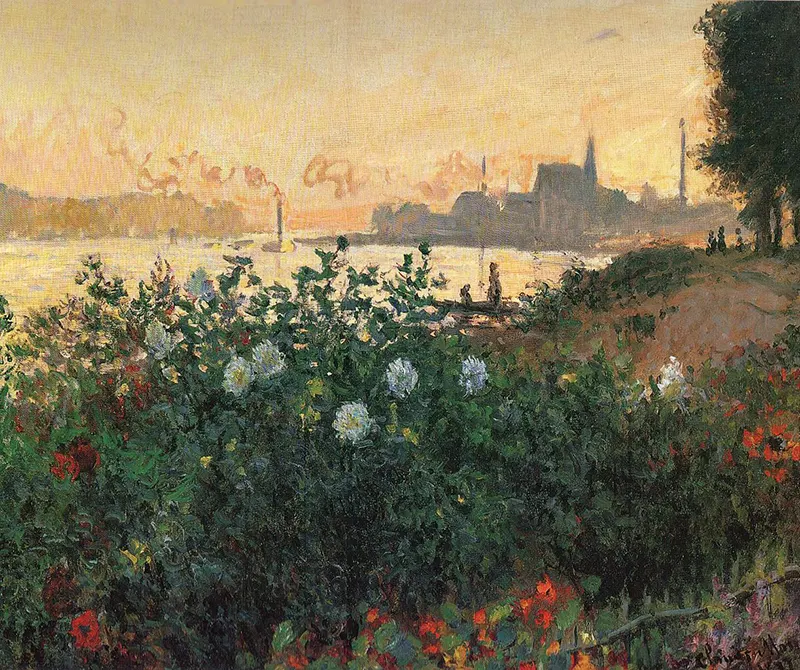

Foremost among Monet’s Giverny masterpieces were his gardens, split into two main parts: the Clos Normand flower garden in front of the house and the Japanese-inspired water garden. Monet threw himself into their design with the same fervor seen in his paintings. He diverted a river to feed the water garden, which was filled with exotic plants from distant lands, contrasting dramatically with the more traditional Clos Normand.

The Clos Normand broke away from the structured, symmetrical gardens of the time, instead bursting with metal arches and trellises supporting climbing and rambling roses. The flowerbeds were densely packed and composed to provide contrasts in color, height, and volume, creating a wilder, freer effect.

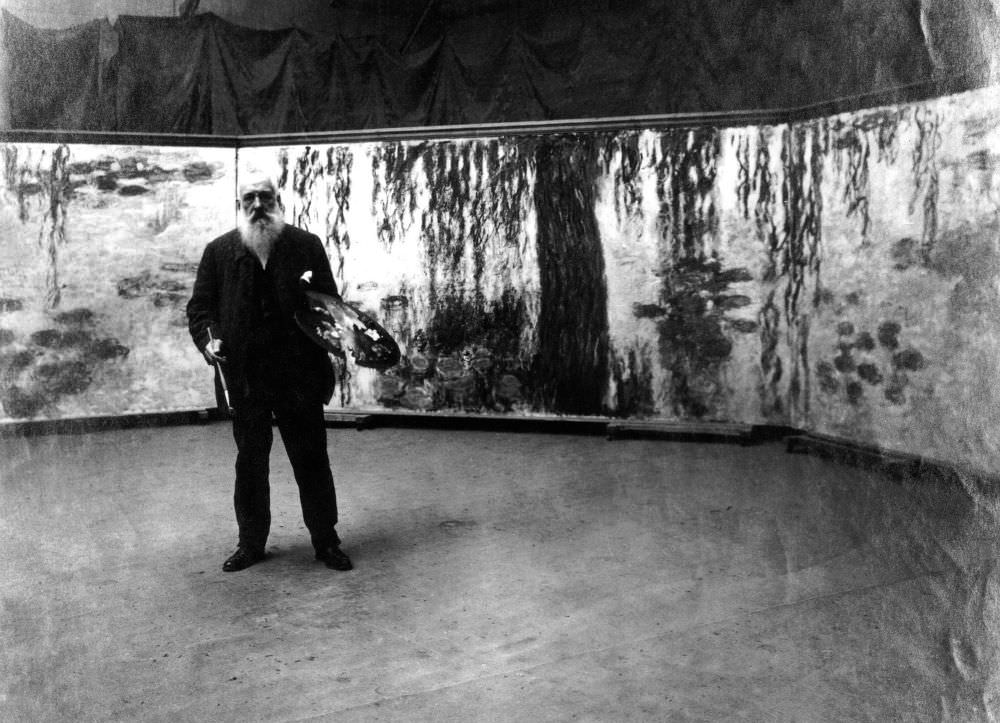

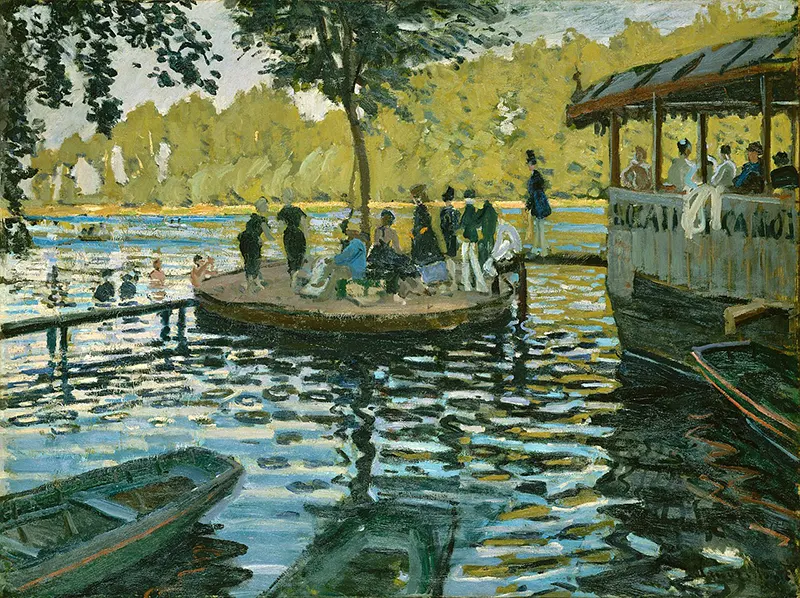

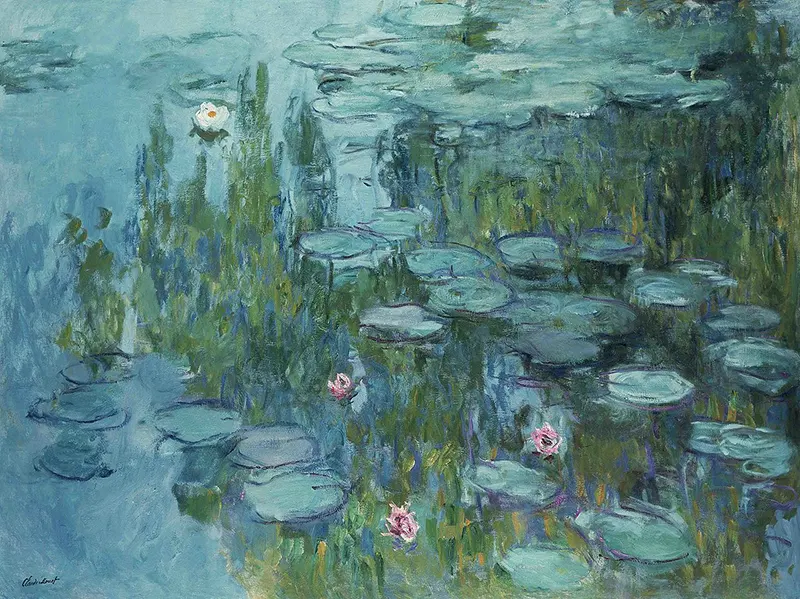

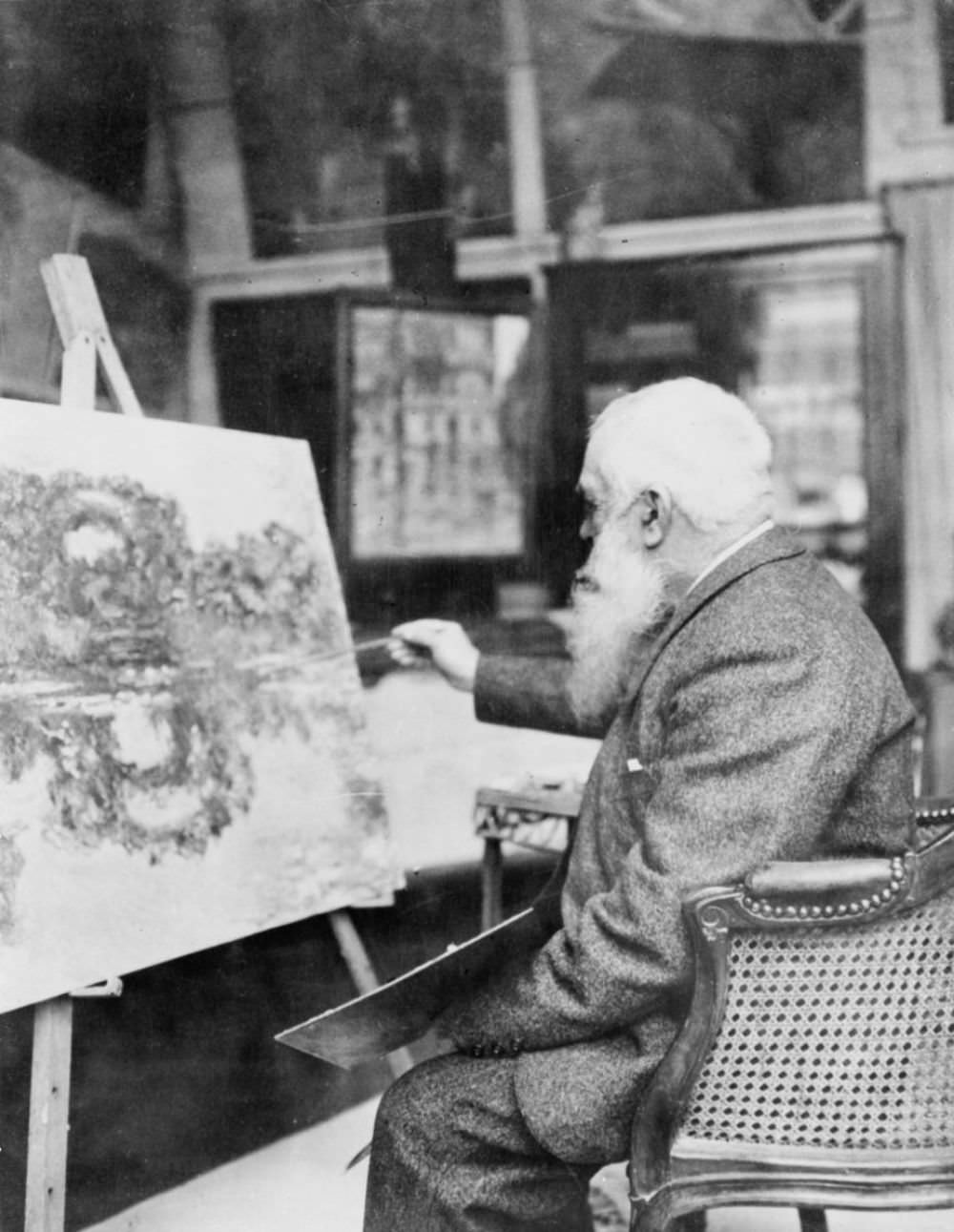

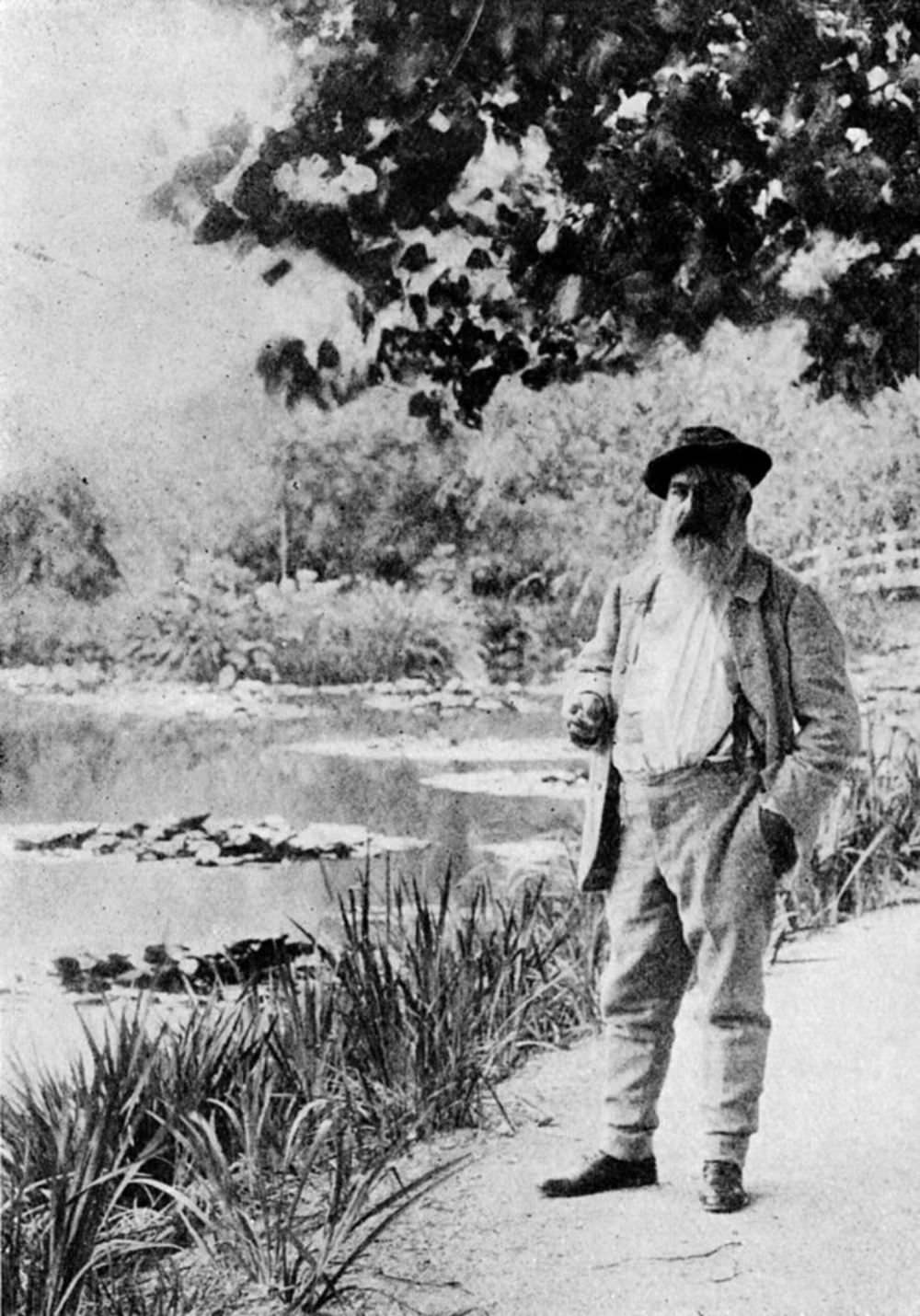

Meanwhile, the water garden, with its famous lily pond, weeping willows, and Japanese bridge, became an ethereal realm. This was Monet’s personal fantasy brought to life, complete with a misty, watery landscape that seemed to float between reality and dream. It was here that Monet painted his seminal “Water Lilies” series, the enigmatic and almost abstract reflections on the pond’s surface becoming the subject of endless fascination and interpretation.

Giverny’s Influence on Monet’s Work

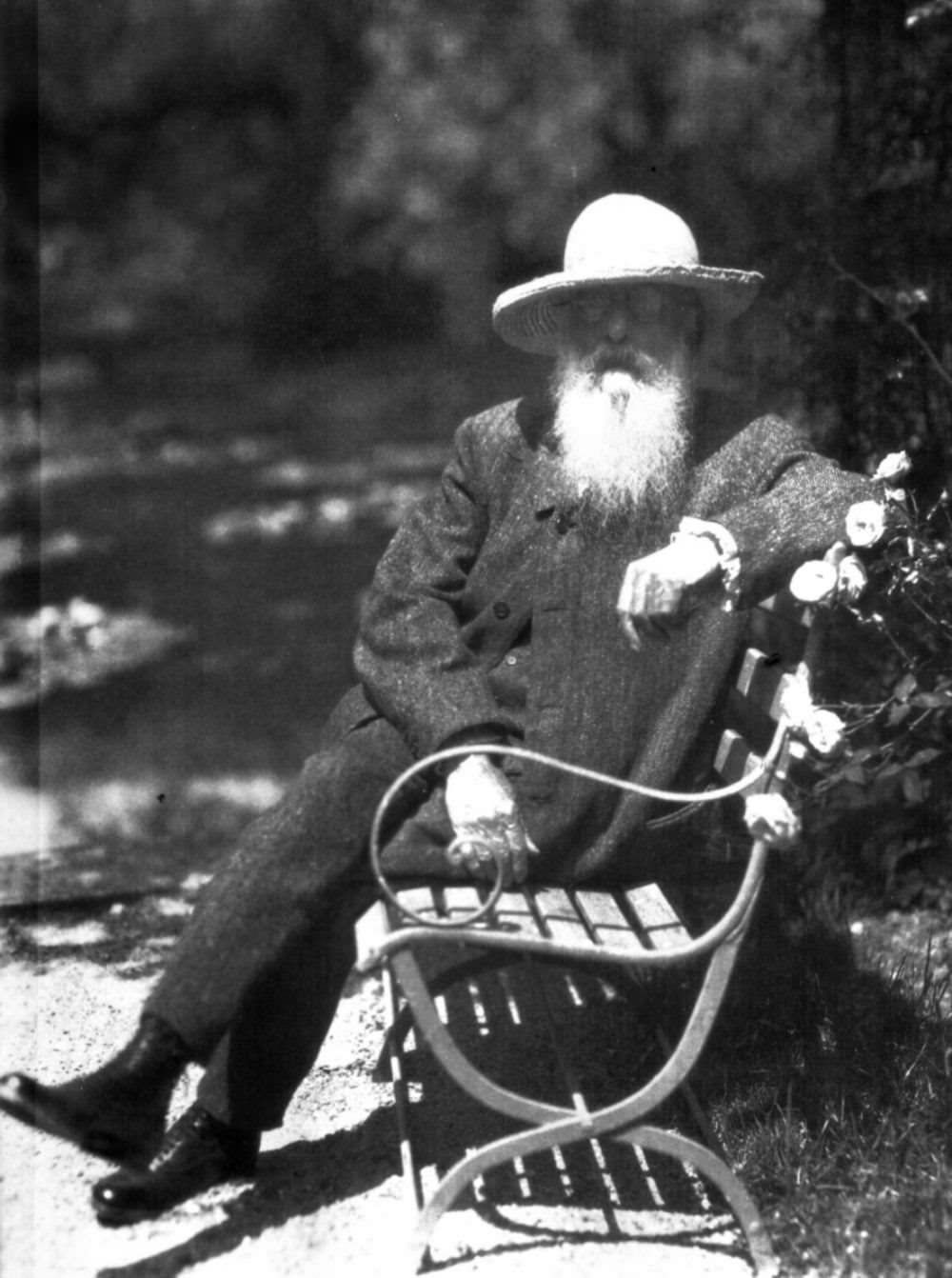

These gardens were not a static backdrop but dynamic participants in Monet’s art. The changing light, the seasons’ ebb and flow, and even the time of day affected how the artist viewed and painted his surroundings. He often worked on many canvases at once, capturing the garden’s transient moods and atmospheres. It was a kind of dialogue between the artist and his environment, a cyclical give-and-take where life imitated art and vice versa.

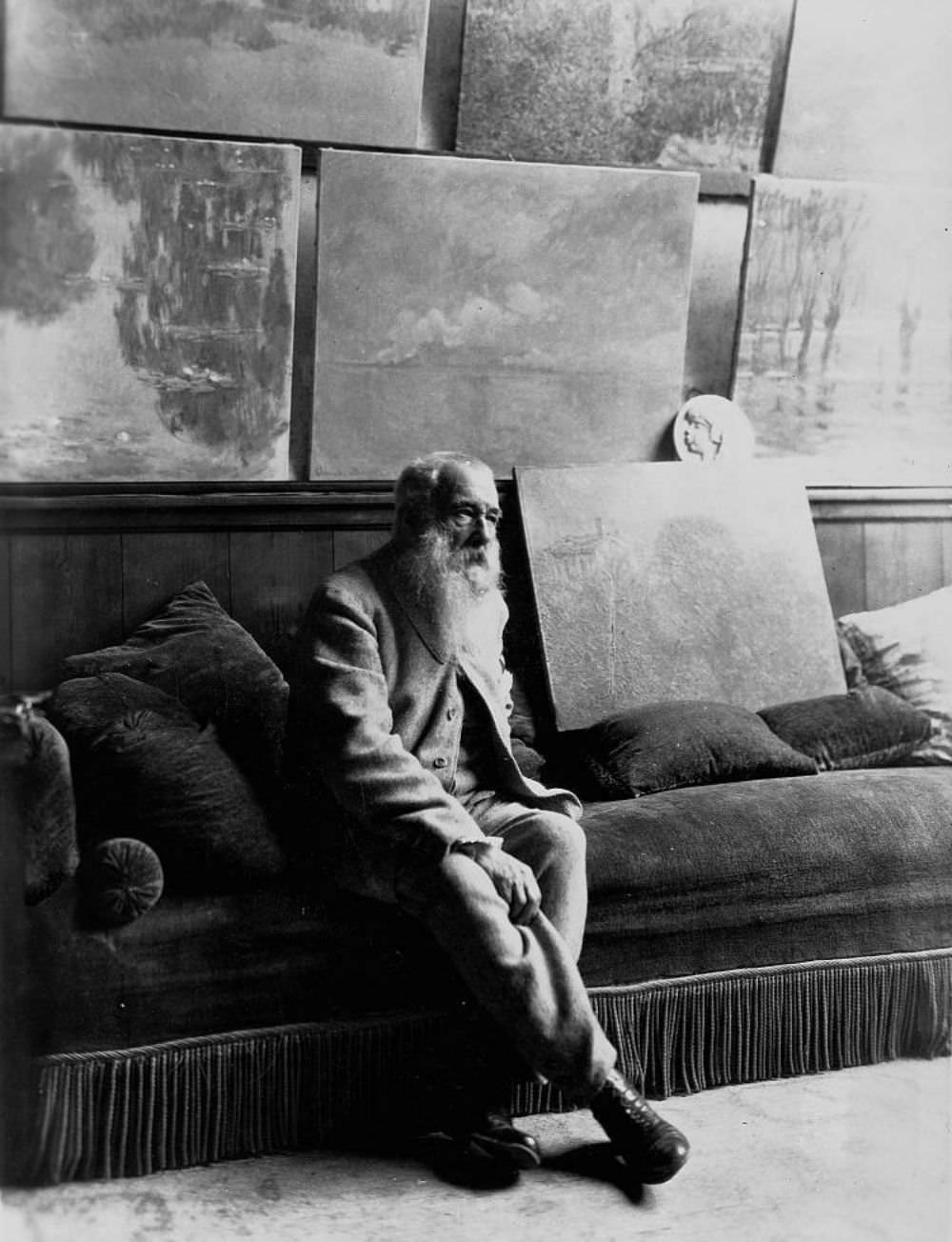

Moreover, Giverny became a haven for inspiration and rejuvenation during Monet’s later years, especially after experiencing personal loss with the passing of his wife Alice and his son Jean. The gardens, in many ways, became Monet’s solace, a personal Eden where he found peace and purpose.

After Monet’s death in 1926, the Giverny estate fell into neglect for several years and underwent restoration in the late 20th century. Today, it stands as a testament to the artist’s bond with nature and his profound understanding of light and color. Visitors walking through the dappled sunlight of the Clos Normand or standing on the Japanese bridge overlooking the water lilies can’t help but feel immersed in a living work of art.