On April 26, 1986, a catastrophic event occurred at the V. I. Lenin Nuclear Power Plant near Chernobyl, Ukraine. Reactor #4 exploded, releasing 400 times more radioactive material than the Hiroshima bomb. Igor Kostin, a photographer for the Novosti Press Agency in Kiev, was one of the first to document this disaster. His photos reveal the true extent of the devastation and the haunting aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Kostin received a call on the night of the explosion from a helicopter pilot who informed him about a fire at the nuclear power plant. Despite the fire being extinguished by the time they arrived; the scene was chaotic. Military vehicles and plant personnel scrambled around the site. Kostin described an unusual feeling in the air, with high temperatures and toxic smog filling the environment. This was not a typical accident scene..

Read more.

As Kostin began taking photos, he noticed something strange. After about 20 shots, the motor of his camera started to fail. The high levels of radiation were affecting his equipment. Despite this, he managed to take some photos before the helicopter had to return to Kiev due to the camera’s failure.

When Kostin developed the films, he found that most of the images were unsalvageable. The radiation had damaged the films, causing them to appear completely black, as if they had been exposed to light prematurely. However, one photograph survived. This image of the nuclear power plant, showing the scale of the disaster, was sent to Novosti in Moscow. But due to the Soviet government’s censorship, he didn’t receive permission to publish it until May 5, 1986.

At that time, the Soviet media was heavily censoring information about the accident. Pravda, a leading Soviet newspaper, published limited information on April 29, 1986, but did not include Kostin’s photographs. The government wanted to control the narrative and downplay the severity of the disaster. It wasn’t until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 that more information about Chernobyl and Kostin’s photographs became widely known.

Kostin’s aerial view of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was widely published around the world once the information was no longer censored. His images showed the true extent of the devastation, with the reactor building in ruins and the surrounding area heavily contaminated. These photographs triggered fear and concern worldwide about the dangers of nuclear energy and the long-term effects of radiation exposure.

Kostin’s dedication to his work and his bravery in capturing these images cannot be overstated. He risked his health and his life to document the disaster. The radiation exposure he endured while taking these photographs had severe consequences on his health later in life. Despite the dangers, Kostin felt it was his duty to show the world what had happened at Chernobyl.

The images he captured are haunting. They show abandoned buildings, empty streets, and a landscape that looks more like a war zone than a place where people once lived and worked. One particularly striking image shows a ferris wheel in Pripyat, the nearby town that was evacuated after the disaster. The ferris wheel stands eerily still, a symbol of the lives that were disrupted and the innocence that was lost.

Kostin’s photographs also show the efforts of the cleanup crews, known as liquidators, who worked tirelessly to contain the radiation and prevent further contamination. These men and women, many of whom were soldiers, engineers, and firefighters, faced extreme dangers as they tried to stabilize the situation. Kostin’s images capture the heroism and sacrifice of these individuals.

The Chernobyl disaster had far-reaching effects. The radiation spread across Europe, and the long-term health consequences are still being studied today. Many people who lived near Chernobyl developed serious illnesses, and the area remains uninhabitable. Kostin’s photographs serve as a powerful reminder of the potential dangers of nuclear energy and the importance of safety and transparency in its use.

#1 Kostin discovered this deformed child in a special school for abandoned children in Belarus, 1988.

The photo was published in the local Belarus press and the boy nicknamed ‘the Chernobyl Child’. It was then subsequently printed in German magazine Stern and became a world-famous image. The child was adopted by a British family, underwent several operations and is now living a relatively normal life

#2 This is the first photograph ever taken of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, and the only photo that survives from the morning of the accident.

Igor Kostin was a photographer from Kiev who became world famous for his images of the the clean-up operation. The image is very noisy because the radiation was destroying the film in his camera. Of all the shots he took on that flight, this is the only one that wasn’t ruined.

#3 Liquidators clean the roof of the No. 3 reactor.

At first, workers tried clearing the radioactive debris from the roof using West German, Japanese, and Russian robots, but the machines could not cope with the extreme radiation levels so authorities decided to use humans. In some areas, workers could not stay any longer than 40 seconds before the radiation they received reached the maximum authorized dose a human being should receive in his entire life.

#4 The majority of the liquidators were reservists ages 35 to 40 who were called up to assist with the cleanup operations or those currently in military service in chemical-protection units.

The army did not have adequate uniforms adapted for use in radioactive conditions, so those enlisted to carry out work on the roof and in other highly toxic zones were obliged to cobble together their own clothing, made from lead sheets and measuring two to four millimeters thick. The sheets were cut to size to make aprons to be worn under cotton work wear, and were designed to cover the body in front and behind, especially to protect the spine and bone marrow.

#5 Liquidators clear radioactive debris from the roof of the No. 4 reactor, throwing it to the ground where it will later be covered by the sarcophagus.

#6 The remains of the No. 4 reactor, photographed from the roof of reactor No. 3.

#7 A team of human liquidators prepares to clear radioactive debris off the roof of the No. 4 reactor.

#8 A liquidator, outfitted with handmade lead shielding on his head, works to clean the roof of reactor No. 3.

#9 A bulldozer digs a large trench in front of a house before burying the building and covering it with earth.

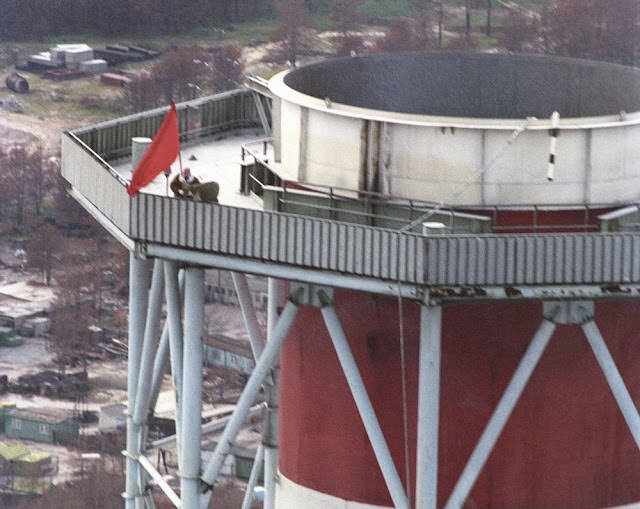

#10 Following orders issued by Soviet authorities to mark the end of cleanup operations on the roof of the No. 3 reactor.

Three men were requested to post a red flag atop the chimney overlooking the destroyed reactor, reached by climbing 78 meters up a spiral staircase. The flag bearers were sent despite the dangers posed by heavy radiation, and after a group of liquidators had already made two failed attempts by helicopter. The radiation expert Alexander Yourtchenko carried the pole, followed by Valéri Starodoumov with the flag, and Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Sotnikov with the radio. The whole operation was timed to last only 9 minutes, given the high radiation levels. At the end, the trio were rewarded with a bottle of Pepsi (a luxury in 1986) and a day off.

#11 A helicopter decontaminates the disaster site on May 5, 1986.

After the explosion, the nuclear power station was covered in radioactive dust. Aircraft and helicopters flew over the site, spraying sticky decontamination fluid that fixed the radiation to the ground. Workers known as 'liquidators' then rolled the dried remains like a carpet and buried the nuclear waste.

#12 At Moscow’s No. 6 clinic, which specializes in radiation treatment, a patient recovers after a bone-marrow operation.

#13 May 1986: In the 30km no-go zone around the reactor, liquidators measure radiation levels in neighboring fields using antiquated radiation counters, wearing anti-chemical warfare suits that offer no protection against radioactivity, and “pig muzzle” masks. The young plants will not be harvested, instead used by scientists to study genetic mutations in plants.

#14 After the evacuation of Chernobyl on 5 May, 1986, liquidators wash the radioactive dust off the streets using a product called “bourda”, meaning molasses. Chernobyl had about 15,000 inhabitants before the accident.

#15 Dead fish are collected by an artificial lake within the Chernobyl site that was used to cool the turbines, June 1986.

#16 The majority of liquidators were men called up from military reserves because of their experience in clean-up operations or chemical protection units in the summer of 1986.

The army did not have adequate uniforms for use in radioactive conditions, so those enlisted had to cobble together their own clothing made from lead sheets measuring 2-4mm thick. These sheets were cut to size to make aprons covering their bodies in front and behind, especially to protect the spine and bone marrow. “The clever ones also added a vine leaf for extra comfort,” said Kostin.

#17 To mark the end of the clean-up operation atop reactor 3, the authorities ordered three men to attach a red flag to the summit of the chimney.

A group of liquidators had already made two fruitless attempts by helicopter, so the three men had to climb the 78 metre chimney via a spiral staircase, despite the dangerous radiation levels. Radiation expert Alexander Yourtchenko carried the pole, followed by Valéri Starodoumov with the flag, while lieutenant-colonel Alexander Sotnikov ascended with the radio. The whole operation was timed to last only 9 minutes given the high radiation levels. At then end, the trio were rewarded with a bottle of Pepsi (a luxury in 1986) and a day off.

#18 In a specialist radiation unit in Moscow, a liquidator is examined by a doctor in a sterile, air-conditioned room after an operation, January 1987.

#19 The village of Kopachi is buried, house by house in August 1987.

It was located 7km from the Chernobyl reactor that housed the control room and decontamination area in the months after the disaster. A bulldozer would dig a large trench in front of each house before burying the building and covering it with earth and flattening the soil. Entire villages would be buried this way..