Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia in April 1992. However, within the following years, the Bosnian Serb forces, backed by the Yugoslav army, committed atrocities against Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) and Croatian civilians, killing 100,000 (80% Bosniaks) by 1995.

Background of the conflict

The Balkan states of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia, and Macedonia became part of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia after World War II. Following the death of longtime Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980, growing nationalism threatened to break up the Yugoslav union. After the mid-1980s, the rise of Slobodan Milosevic fomented discontent between Serbians in Bosnia and Croatia and their Croatian, Bosniak, and Albanian neighbors. As a result, Slovenia, Croatia, and Macedonia declared independence in 1991. Following the war in Croatia, the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army supported Serbian separatists in brutal clashes with Croatian forces.

By 1971, Muslims were the largest single population group in Bosnia. However, during the following two decades, more Serbs and Croats emigrated, and by 1991, Bosnia’s population of just over 4 million consisted of 44 percent Bosniaks, 31 percent Serbs, and 17 percent Croats.

A coalition government was formed in late 1990 by parties representing all three ethnicities (roughly proportional to their populations), led by the Bosniak Alija Izetbegovic. On March 3, 1992, Bosnia gained independence after a referendum vote (which Karadzic’s party blocked in many Serb-populated areas) following rising tensions within and outside the country.

Serbian separatists long envisioned a “Greater Serbia” consisting of a dominant Serbian state in the Balkans rather than independence for Bosnia. Two days after the United States and European Community (the precursor to the European Union) recognized Bosnia’s independence, Bosnian Serb forces, backed by Milosevic and the Yugoslav army, began bombarding Sarajevo the capital of Bosnia.

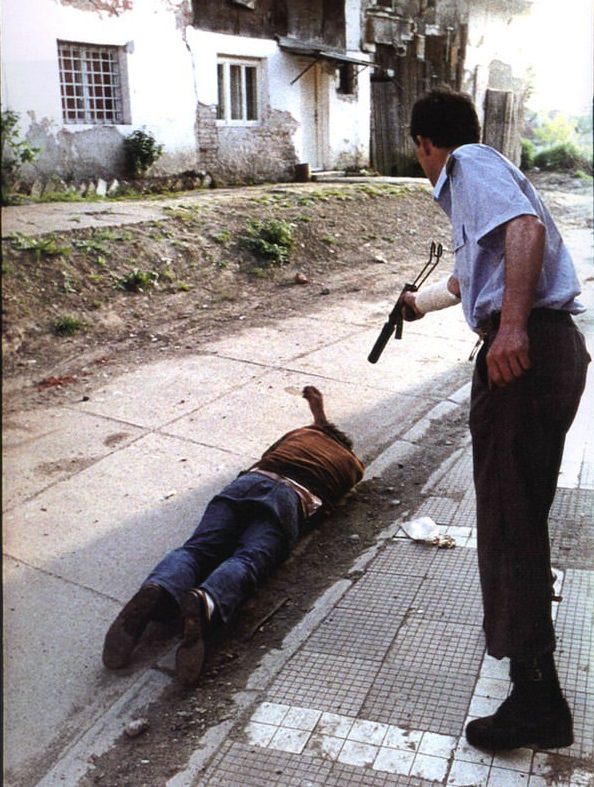

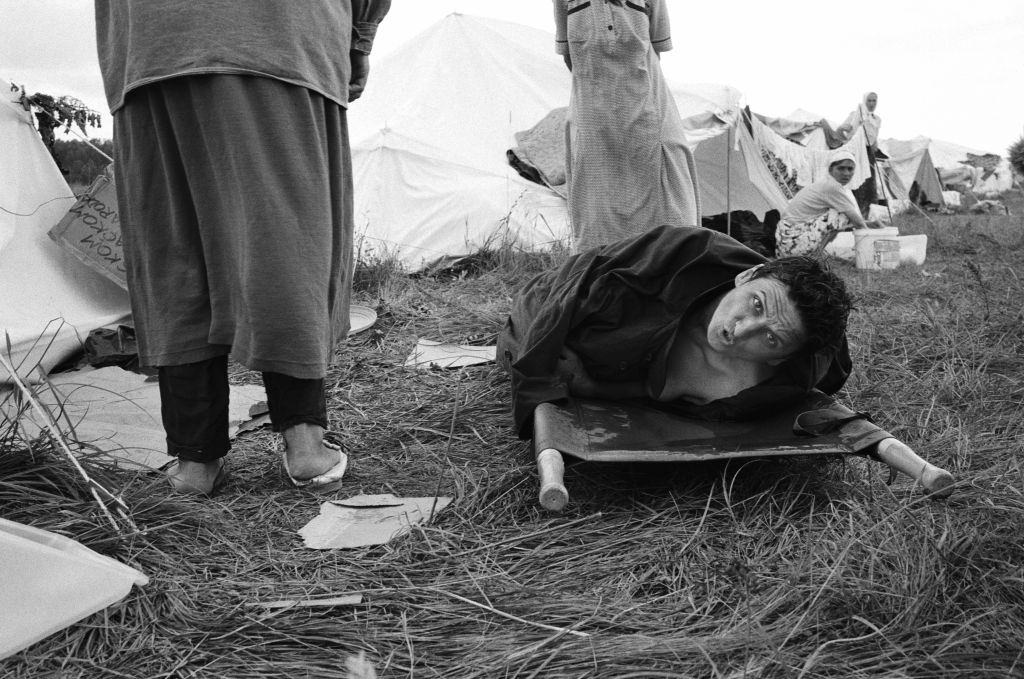

During their attacks on Bosniak-dominated towns in eastern Bosnia, such as Zvornik, Foca, and Visegrad, they expelled Bosniak civilians from the region in a brutal process later called “ethnic cleansing.” Despite Bosnian government forces’ efforts to defend the allies sometimes with the help of the Croatian army, Bosnian Serb forces controlled more than three-quarters of the country by the end of 1993, with Karadzic’s party setting up their republic in the east. A significant Bosniak population remained only in small towns, while most Bosnian Croats left the country.

Croatian-Bosnian peace proposals failed when Bosnian Serbs refused to give up any territory. As a result, U.N. did not intervene in the Bosnian War, but the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugee assisted its displaced, malnourished, and injured victims.

Srebrenica Massacre

In 1995, Bosnian troops controlled three towns in eastern Bosnia: Srebrenica, Zepa, and Gorazde. These enclaves were declared “safe havens” by the U.N. in 1993, to be disarmed and protected by international peacekeepers.

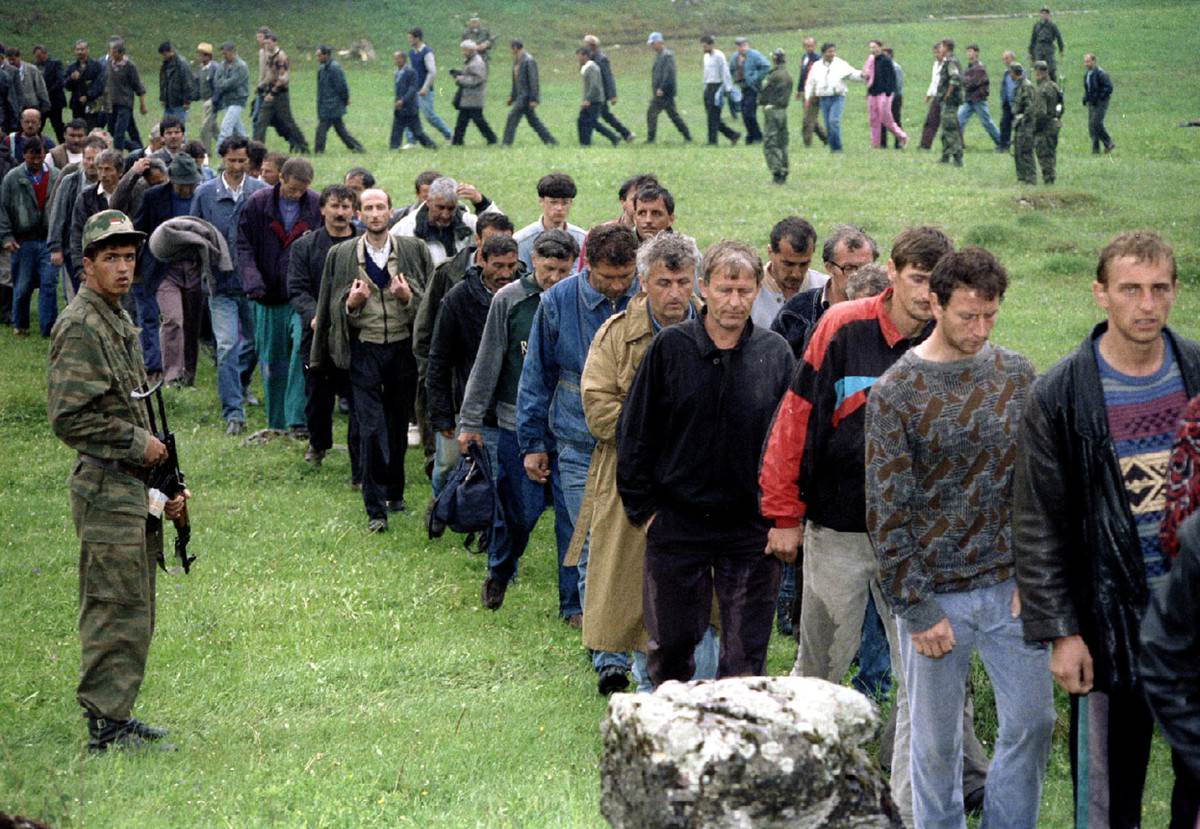

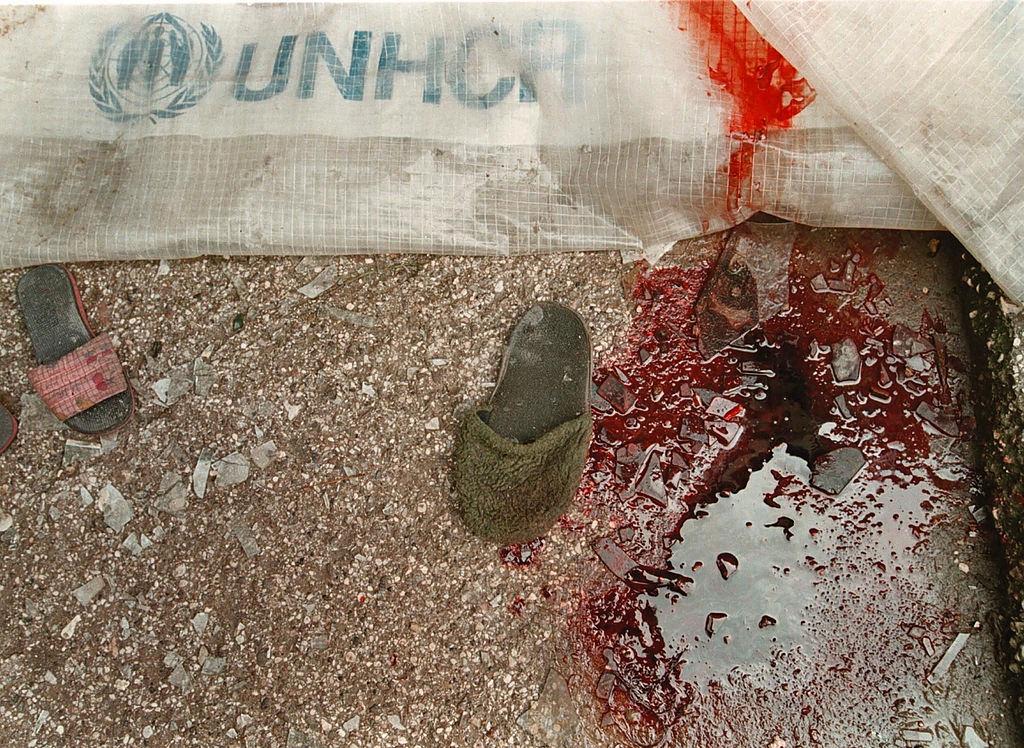

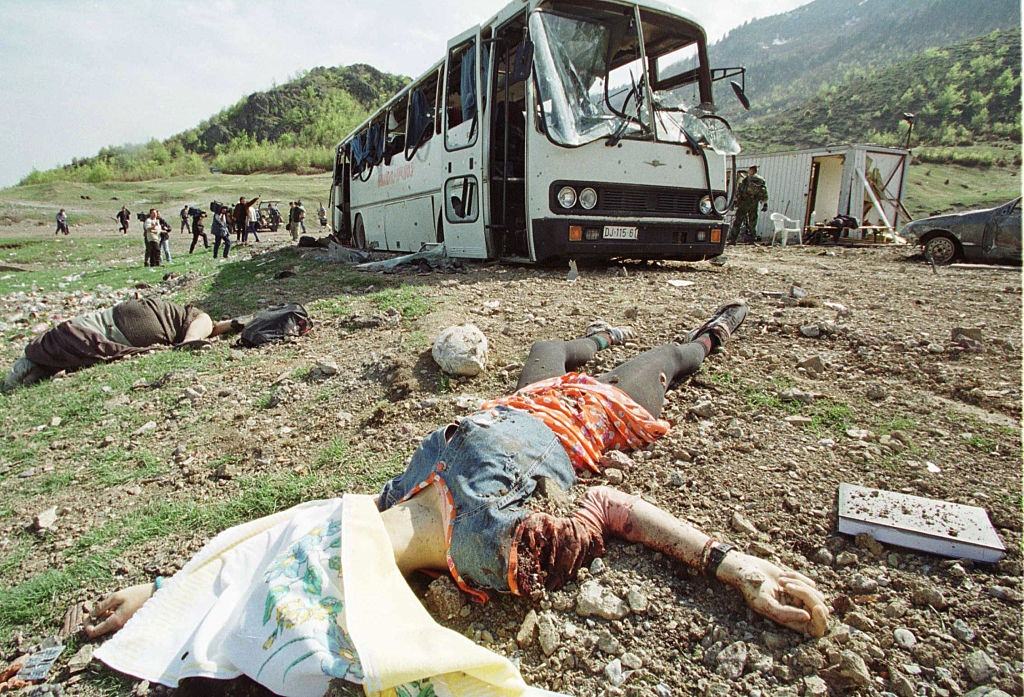

Bosnian Serb forces advanced on Srebrenica on July 11, 1995, overwhelming Dutch peacekeepers. The Bosniak civilians were then separated by Serbian forces at Srebrenica, entering Bosnian-held territory on buses. Women were raped or assaulted, while the men and boys who remained were killed immediately or bussed to mass killing sites. Serb forces killed around 7,000 to more than 8,000 Bosniaks at Srebrenica. Although in April of that year, Bosnian Serb forces seized Zepa. In a crowded Sarajevo market, a bomb exploded, the international community responded forcefully to the ongoing conflict and its ever-growing civilian death toll.

After the Serbs refused to comply with a U.N. ultimatum in August 1995, NATO teamed up with Bosnian and Croatian forces to bomb and assault Serb positions. U.N. trade sanctions crippled Serbia’s economy, and its military forces were under attack in Bosnia after three years of War, so Milosevic agreed to negotiate that October. In November 1995, U.S.-sponsored peace talks in Dayton, Ohio (which included Izetbegovic, Milosevic, and Croatian President Franjo Tudjman) created a federalized Bosnia.

The aftermath of the Bosnian Genocide

Although the international community did little to stop systematic atrocities in Bosnia, it sought to hold those responsible to account. The United Nations Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 1989. Since the Nuremberg Trials in 1945-46, this was the first international tribunal and the first to prosecute Genocide. The tribunal indicted Radovan Karadzic and Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladic for genocide and crimes against humanity.

One hundred sixty-one individuals were ultimately accused of crimes during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia by the ICTY. Having served as his defence lawyer, Milosevic was brought before the tribunal in 2002 on charges of Genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes; his poor health delayed the trial until 2006 when he was found dead in his cell

The International Court of Justice ruled on a historic civil lawsuit brought by Bosnia against Serbia in 2007. The court characterized the massacre at Srebrenica as Genocide. It said Serbia should have prevented and punished those who committed it but did not find Serbia itself guilty of the atrocity.

ICTY found Mladic guilty of Genocide and other crimes against humanity in November 2017 after a trial lasting more than four years and involving nearly 600 witnesses. He was sentenced to life imprisonment by the tribunal. Following Karadzic’s conviction for war crimes the previous year, Mladic’s long-delayed conviction marked the ICTY’s last major prosecution.

One Comment