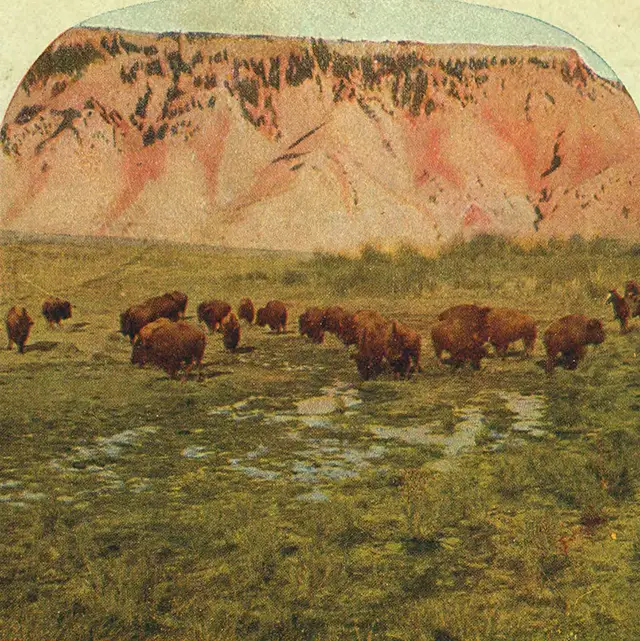

The American bison, often called the buffalo, once roamed the Great Plains in vast herds. These animals were central to the lives of Native American tribes, providing food, clothing, shelter, and spiritual meaning. However, as the United States expanded westward in the 19th century, the bison faced near extermination. This tragedy was driven by greed, rapid development, and a lack of understanding of the ecosystem.

In the early 1800s, the United States began to expand westward. This period, known as Manifest Destiny, encouraged settlers to move across the continent. The Great Plains, home to millions of bison, became a target for settlers, ranchers, and hunters. The arrival of the railroad connected the eastern and western parts of the country, making travel and trade easier. Towns sprang up along the railway lines, attracting settlers eager to make a profit.

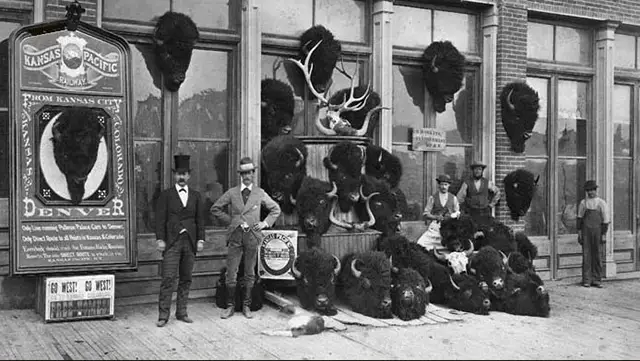

As railroads expanded, so did the demand for bison products. Bison fur, meat, and hides were valuable commodities. Meat was shipped eastward to feed the growing population, while hides were used for clothing and other goods. The bison trade boomed, drawing hunters from all over. This increased hunting pressure had a devastating impact on bison populations.

Native American Hunting Practices

Before European settlers arrived, Native American tribes had developed effective methods for hunting bison. They used techniques like buffalo pounds and buffalo jumps. Buffalo pounds were large enclosures made of rocks and branches where bison were trapped. Once inside, hunters would kill the animals for food and materials. Buffalo jumps involved driving bison over cliffs, allowing them to fall to their deaths. These methods required skill and cooperation among tribe members, showing their deep understanding of bison behavior.

Read more

When horses were introduced to the Americas by Spanish explorers in the 1500s, hunting techniques changed dramatically. By the early 1700s, many Native American tribes had adopted horses, allowing them to hunt more efficiently. They could follow migrating herds and cover larger distances. This shift transformed hunting cultures, as tribes adapted their methods to include mounted chases. Bison became even more central to their way of life, providing food, clothing, and tools.

The Shift After the Civil War

The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked a new era in American history. With the war over, the United States turned its attention to westward expansion. The demand for bison products surged, fueled by the growing railroads and towns. Settlers and hunters flooded into the Great Plains, eager to take advantage of the seemingly endless supply of bison. Unfortunately, this surge in hunting led to a rapid decline in bison populations.

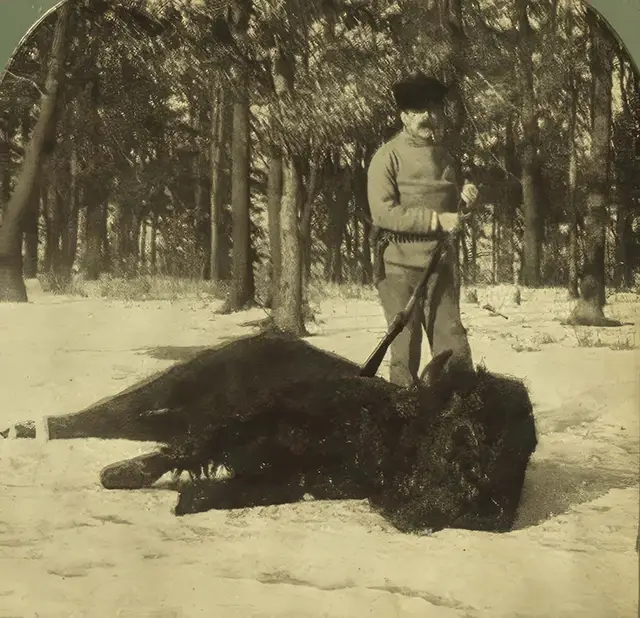

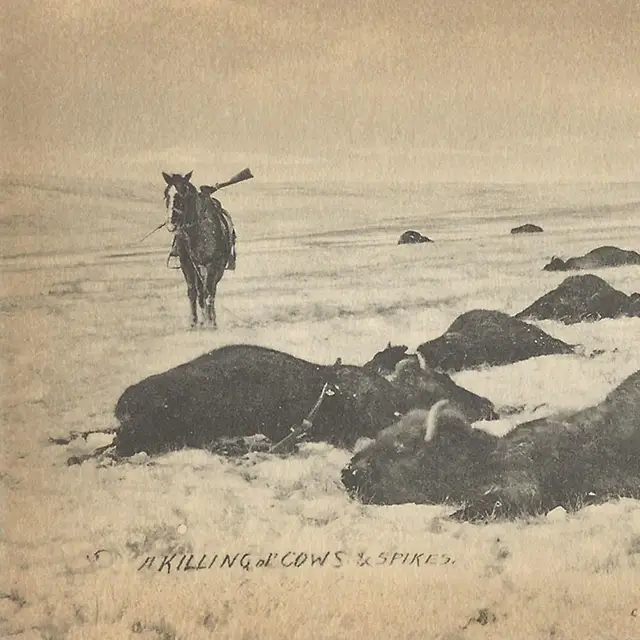

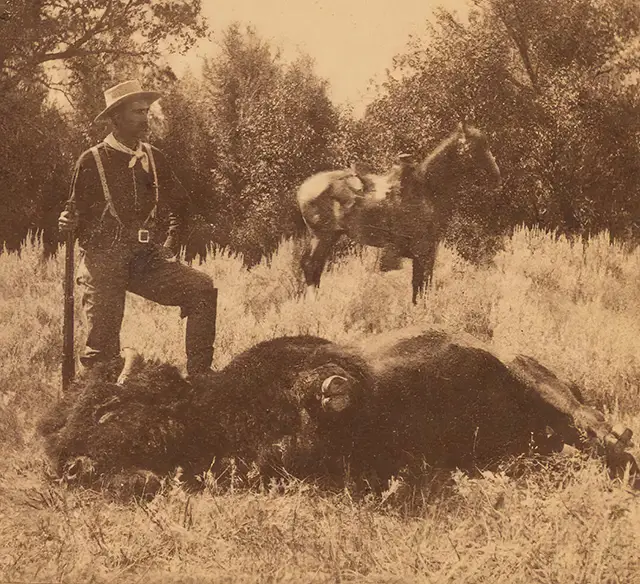

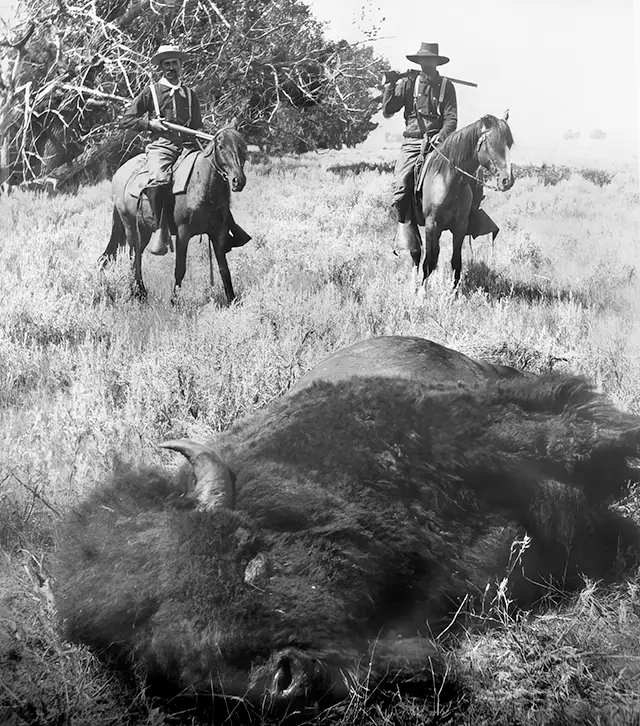

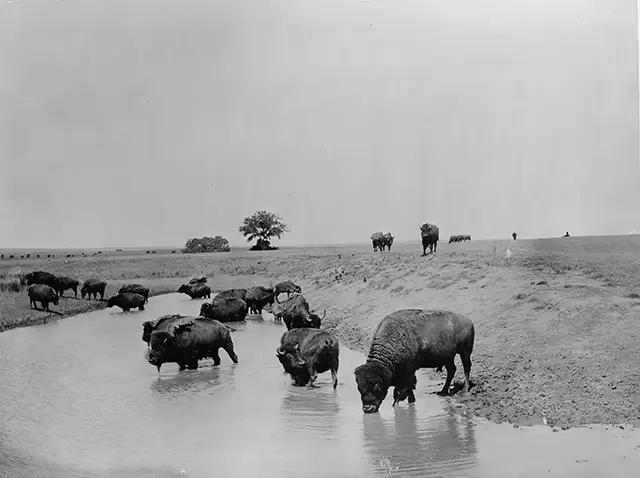

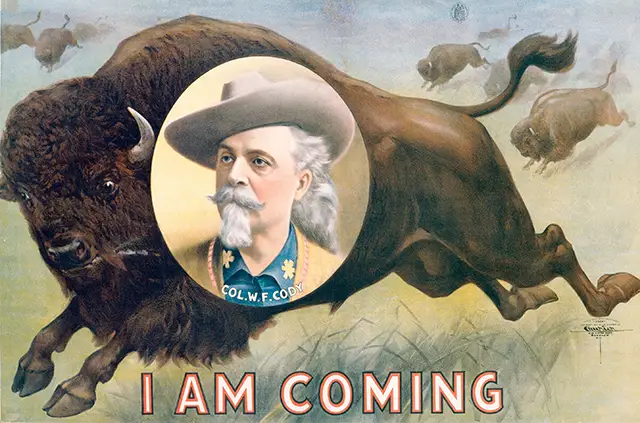

By the 1860s, bison herds that had once numbered in the tens of millions were being decimated. The bison were no longer seen as a vital resource for Native Americans; instead, they became targets for commercial hunters. These hunters sought profit rather than sustenance. They would shoot bison from moving trains, often leaving the carcasses to rot. This practice was not only wasteful but also cruel.

Methods of Extermination

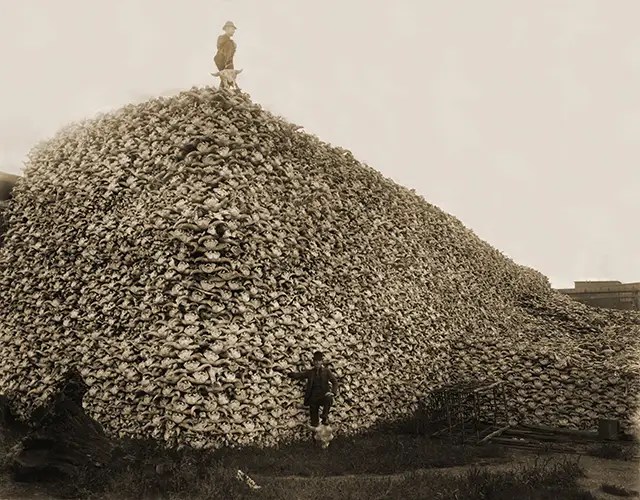

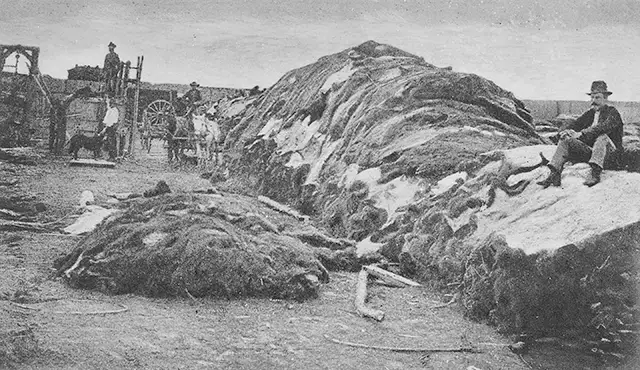

The methods used for bison extermination were shocking. Professional hunters sought to kill as many bison as possible, often for their hides, which were highly valued in the market. Some hunters would shoot bison from the comfort of train cars. This method was not only easy but also incredibly effective. The bison had little chance to escape, and many were killed for sport rather than necessity.

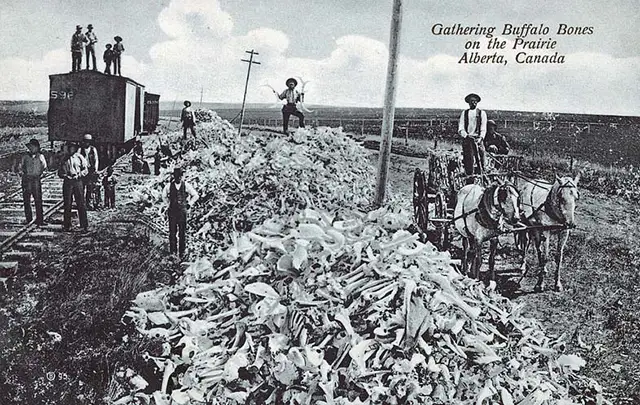

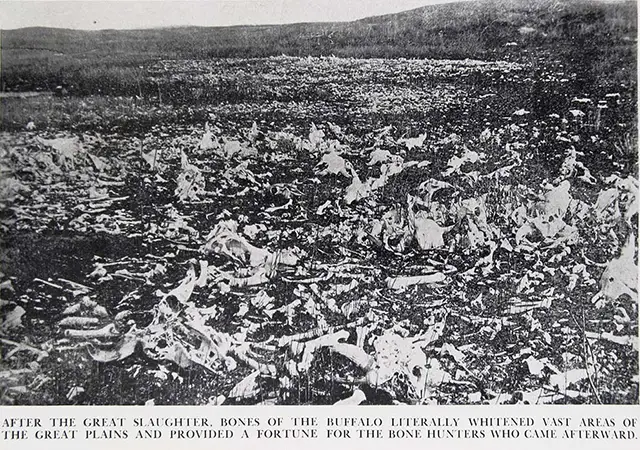

The sheer scale of the slaughter was staggering. In the early 1870s, it is estimated that around 1 million bison were killed each year. By the mid-1880s, this number had drastically reduced, and bison herds that once roamed freely were nearly gone. The population plummeted from an estimated 30 million bison in the early 1800s to just a few hundred by the late 1800s. This rapid decline marked one of the most significant wildlife extinctions in history.

The Aftermath of Extermination

The extermination of the bison had severe consequences for Native American tribes. As bison populations dwindled, tribes lost their primary source of food and materials. This loss led to hunger and poverty. Many tribes were forced onto reservations where they could no longer hunt freely. The traditional ways of life that had sustained Indigenous peoples for generations were shattered.

In addition to this, the ecosystem of the Great Plains suffered dramatically. The bison played a crucial role in maintaining the health of the plains. Their grazing patterns helped shape the landscape, promoting the growth of diverse plant species. The disappearance of the bison led to changes in the plant and animal communities, disrupting the balance of the ecosystem.

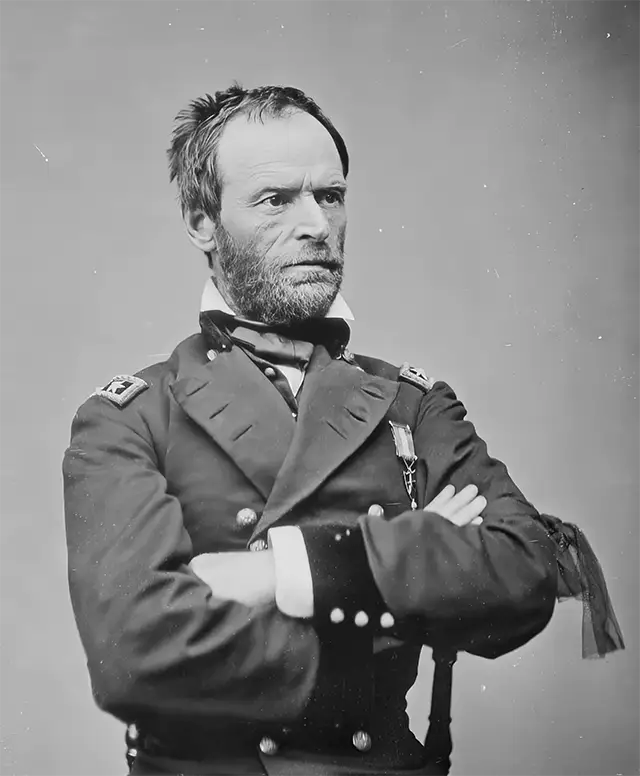

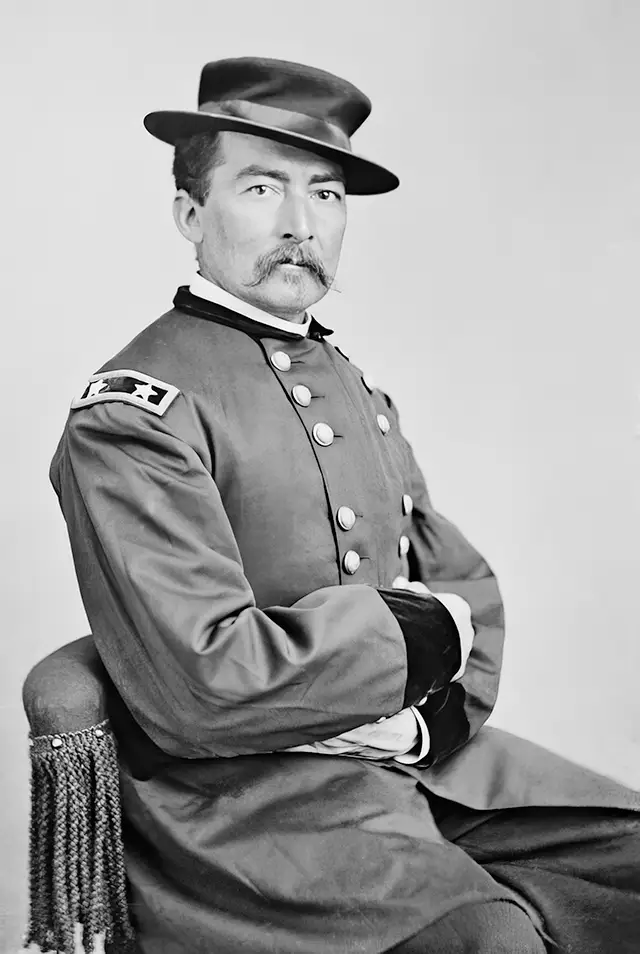

Government Policies and Military Involvement

Government policies also played a role in the extermination of the bison. The U.S. government encouraged the slaughter of bison as a way to force Native American tribes onto reservations. By eliminating their primary food source, the government aimed to weaken the tribes’ resistance to relocation. The military was often involved in these efforts, providing support to hunters and settlers.

In some cases, soldiers were directly involved in the killing of bison. They would participate in hunts or support hunters by providing protection and resources. This collaboration between the government and commercial hunters accelerated the decline of bison populations.

Efforts to Preserve the Bison

As the bison population reached critical lows, efforts to preserve the species began. Some individuals and organizations recognized the importance of the bison and sought to protect them. Ranchers like Charles Goodnight and James “Scotty” Philip established private herds to save the remaining bison. These early conservation efforts helped prevent the complete extinction of the species.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. government also began to take action. Wildlife refuges were established to provide safe habitats for bison. The American Bison Society, founded in 1905, played a key role in these efforts. The society worked to raise awareness about the plight of the bison and advocated for their protection.

The Role of Bison in Modern Conservation

Today, bison are considered a conservation success story. From a few hundred individuals in the late 1800s, the population has rebounded to around 500,000 bison. This recovery has been aided by continued conservation efforts and the establishment of protected areas. Bison now live in national parks, wildlife refuges, and private ranches across North America.

Modern conservationists recognize the importance of maintaining genetic diversity in bison populations. Efforts are being made to protect the unique genetic traits of different bison herds. This includes the preservation of wild bison in places like Yellowstone National Park, where bison have lived continuously since prehistoric times.