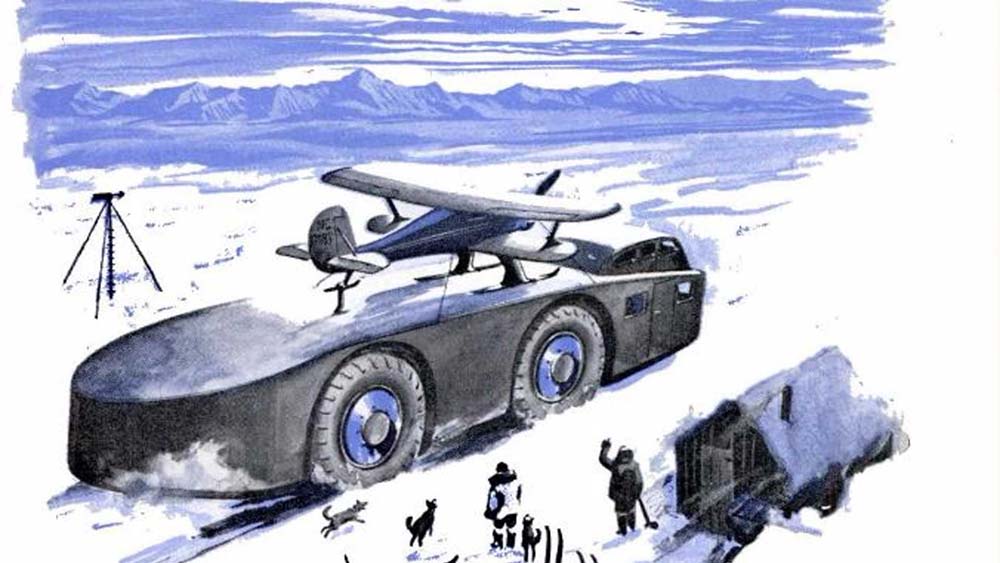

Admiral Richard Byrd designed the Antarctic Snow Cruiser to facilitate transportation in Antarctica as part of the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition from 1939–1941. During a previous Antarctic expedition (in 1934), his second-in-command, Dr Thomas Poulter, came up with the idea for a massive, purpose-built vehicle to carry people and equipment. It was designed to travel over long distances on the continent’s endless ice and snow fields, especially in the harsh weather.

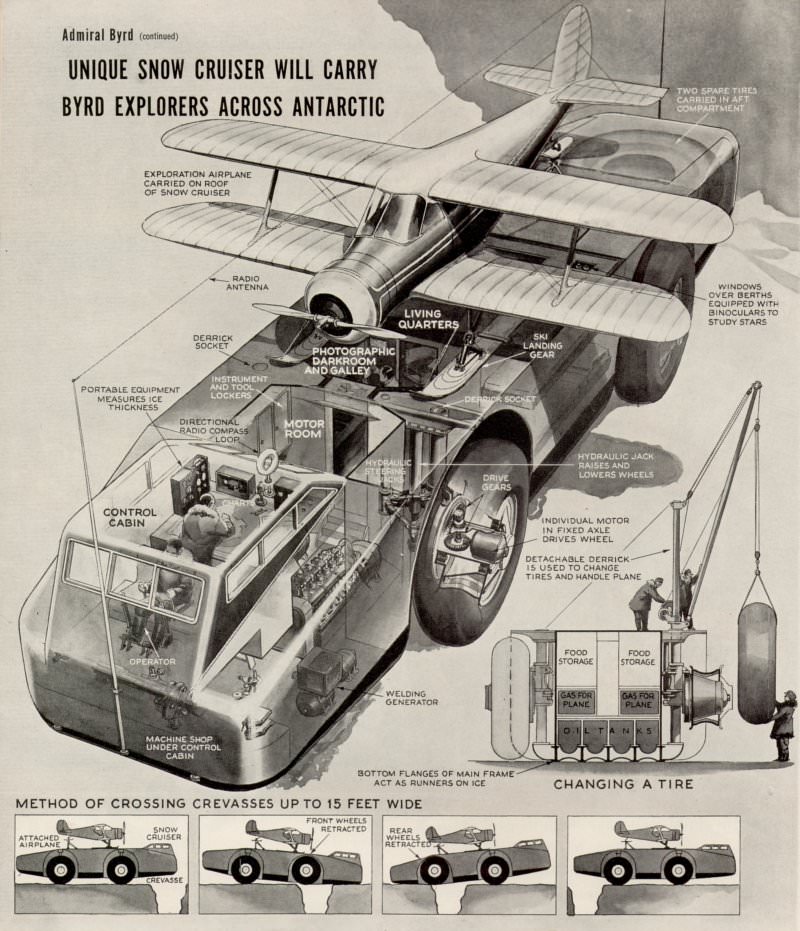

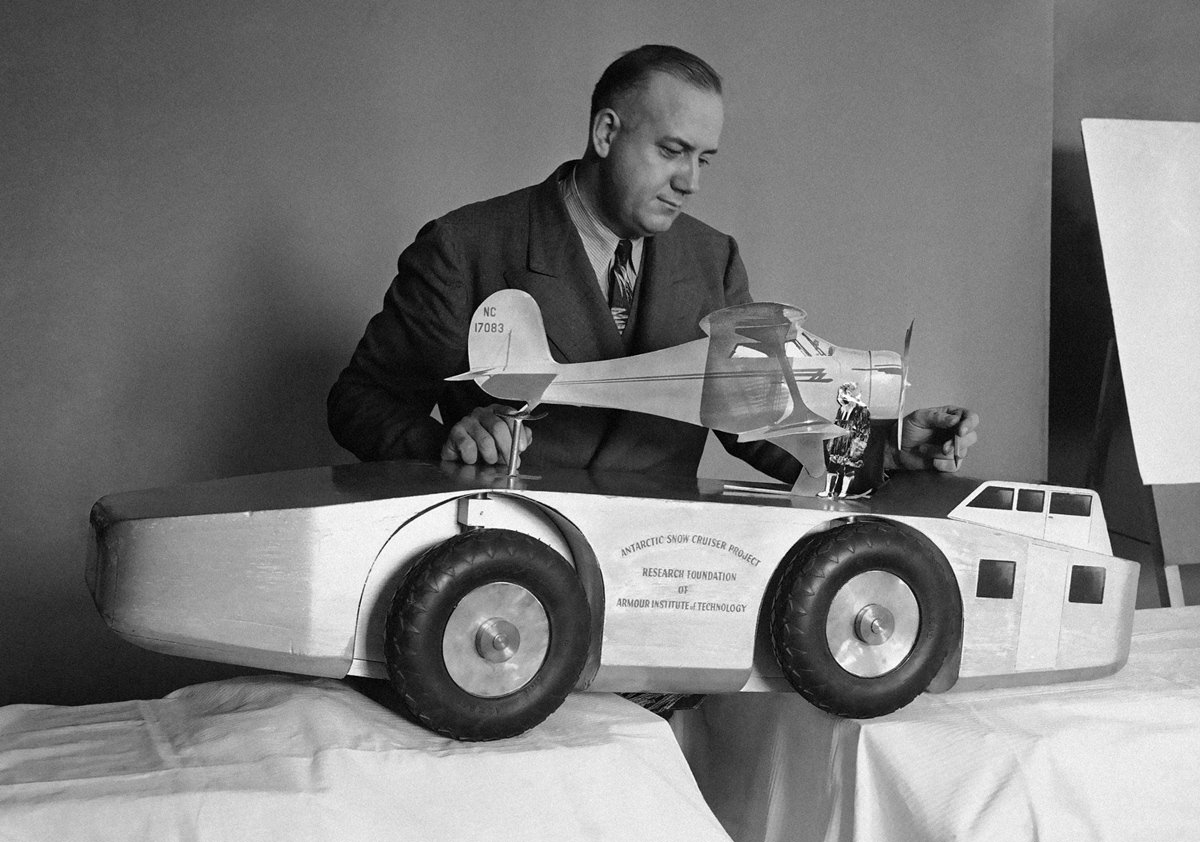

The Antarctic Snow Cruiser was estimated to cost $150,000, and Poulter and The Research Foundation of the Armour Institute of Technology presented the plans to officials in Washington, D.C., on April 29, 1939. The work began on August 8, 1939, and lasted 11 weeks. This vehicle was designed with long overhangs at both ends and retractable wheels to assist in traversing crevasses. The Snow Cruiser was 55 feet (17 meters) long and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide, weighed 45,000 pounds (20 tons) and was designed to house four to five people for a year with all their food, fuel, and equipment. Additionally, it contained a science lab, a photography darkroom, an engine room, and a small machine shop. Each wheel had a diameter of 10 feet (3 meters), weighed 700 pounds (318 kg), and was made from a unique rubber that would not break or crumble in extreme cold. The Snow Cruiser could steer each wheel independently with its motor, allowing it to traverse difficult terrain or cross 15-foot-wide crevasses. Vehicle speeds ranged from 1 to 13 miles (16 to 21 km) per hour, with a maximum speed of 30 miles (48 km). The upper deck is wide enough to accommodate a small airplane. The Snow Cruiser driver and charter sat in an elevated control room up front. The machine shop, snow melter, and various generators, pumps, and hoists were under the control room, beneath a catwalk. There was a pair of Cummins inline-six diesel engines with a combined horsepower of 300 just ahead of the front wheels. Two generators and four electric motors, courtesy of General Electric, combined to provide 300 horsepower.

It was fired up for the first time on October 24, 1939, at the Pullman Company just south of Chicago, before being driven across the Midwest by drivers. The team tested the vehicle on dunes along Lake Michigan in northern Indiana before driving across Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. As the vehicle crossed the country, both lanes were needed. A large crowd of onlookers also gathered to see this giant vehicle. Upon reaching Boston, Massachusetts, they boarded the USCGC North Star for Antarctica on November 15, 1939. Some publications referred to the vehicle as “The Penguin,” “Penguin 1”, or “Turtle”. The Snow Cruiser was supposed to drive to the South Pole to track auroras (light displays caused by charged particles hitting Earth’s magnetic field), but that didn’t happen. It turned out that the machine was far too heavy for the Antarctic snow.

In early January 1940, the Snow Cruiser arrived at Little America with the United States Antarctic Service Expedition in the Bay of Whales, Antarctica. The vehicle needed to be unloaded by building a ramp out of timber. One of the wheels broke through the ramp as the vehicle was unloaded from the ship. Crew members cheered when Poulter powered the vehicle free from the ramp, but the cheers faded when the vehicle stalled in the ice and snow. In the snow, they sank as much as three feet (0.91 m) because they spun freely and provided minimal forward movement. Two spare tires were attached to the vehicle’s front wheels, and chains were installed on the rear wheels, but the crew could not overcome the lack of traction. When the tires were driven backwards, they produced more traction. Ninety-two miles (148 km) were driven reverse over the most extended trek. Poulter returned to the United States on January 24, 1940, leaving F. Alton Wade in charge of a partial crew. Despite its lack of traction and underpowered engines, the Snow Cruiser was an excellent base of operations and full-time living quarters. The cabin’s structure was heated by engine coolant, even in brutally cold conditions.

While living in the wooden Snow Cruiser, the scientists conducted seismologic experiments, cosmic-ray measurements, and ice core sampling. When the U.S. became involved in World War II, Poulter could not return to Antarctica and equip his vehicle with improved parts. The Antarctic Snow Cruiser was abandoned at the Little America III base on December 22, 1940. An expedition team found the vehicle during Operation High jump in late 1946 and discovered it only needed air in the tires and some maintenance. In 1958, an international expedition used a bulldozer to uncover Little America III’s snow cruiser. It was covered by 23 feet of snow and marked by a bamboo pole. The amount of snowfall since it was abandoned was accurately measured by excavating to the bottom of the wheels. Upon entry, the vehicle was exactly as the crew had left, with papers, magazines, and cigarettes scattered everywhere. There was no trace of the vehicle reported by later expeditions. Despite some unsubstantiated speculation, the (traction-less) Snow Cruiser is most likely either at the bottom of the Southern Ocean or buried deep beneath snow and ice. In Antarctica, the ice shelf is constantly moving out to sea, and the ice is constantly moving.

If they remembered to properly test it it would have gone better, but they were on severe time crunch.

It would have worked if they did better suspension and tires on it. The tires it had when I watched a documentary made them seem like they were practically bald tires. How’s it supposed to travel on snow and stuff if it has no traction?

I think it was assumed that they were low pressure enough that it wouldn’t be a problem, this turned out to be a mistake. When they started driving around Antarctica they had severe traction issues. Solutions they tried included makeshift tire chains, doubling up the front wheels, and eventually they discovered it actually made better progress when driven in reverse.

Insane that engineers much smarter than myself thought smooth tires would work in the snow. I guess things that seem obvious aren’t until you try it.

Thunderbirds are go!

ou try it.