The American Civil War, fought from 1861 to 1865, was a brutal and devastating conflict that resulted in the deaths of approximately 620,000 soldiers and an untold number of civilian casualties. In addition to the staggering death toll, many more soldiers suffered debilitating injuries, with amputations being one of the most common and gruesome outcomes. This post will explore the reasons behind the prevalence of amputations during the Civil War, the process of performing such operations, the aftermath for those who underwent them, and the lasting legacy these procedures have left on medical advancements and societal perceptions of disability.

Causes of Amputations during the Civil War

The nature of warfare during the Civil War was particularly conducive to causing severe injuries that often necessitated amputation. Soldiers fought using muskets and cannons, which fired large-caliber bullets and shells capable of shattering bones and causing irreparable damage to limbs. Additionally, the proximity of combatants on battlefields and the widespread use of bayonets and swords led to many traumatic injuries.

Medical knowledge and resources were limited compared to modern standards. Antiseptic practices were not yet widely adopted, and the concept of germ theory was still in its infancy. Consequently, the risk of infection following an injury was high. In many cases, amputation was seen as the only viable option to prevent gangrene and other life-threatening infections.

Amputations were often the treatment of choice for several reasons. Firstly, the extent of damage caused by Civil War weaponry made it difficult to treat injuries conservatively. Secondly, the risk of infection was high, making swift amputations necessary to save lives. Lastly, the sheer number of injured soldiers overwhelmed medical staff, leading to the prioritization of rapid and effective treatments like amputation.

The Process of Amputation during the Civil War

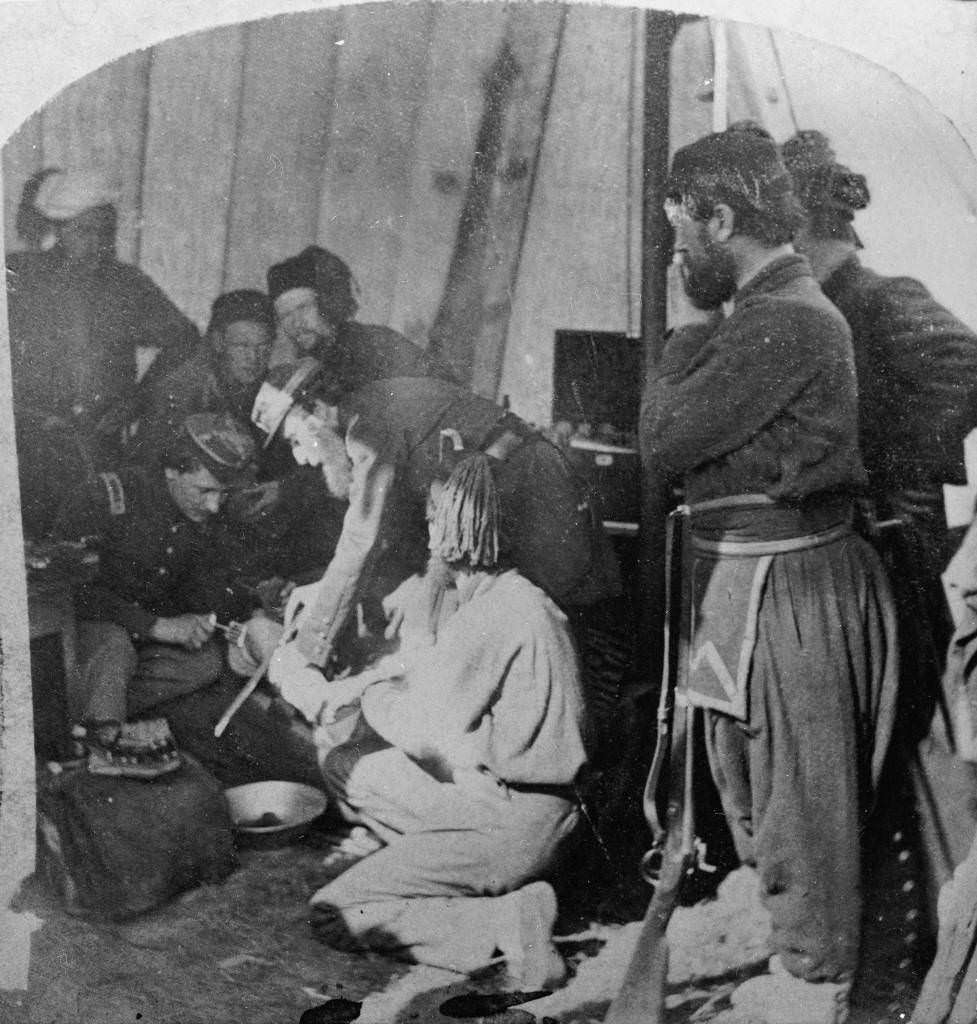

Surgeons played a crucial role in the amputation process during the Civil War. Although they often had limited formal training and experience, they were responsible for performing most of these operations, frequently under challenging conditions and with rudimentary equipment. The surgeons used simple instruments, including knives, saws, forceps, and tourniquets. Anesthesia, often in chloroform or ether, was available but not always utilized due to shortages or urgency. The procedure typically involved the following steps: the administration of anesthesia (when available), the application of a tourniquet to control bleeding, the initial incision through skin and muscle, the cutting of bone using a saw, and the closing of the wound with sutures or cautery.

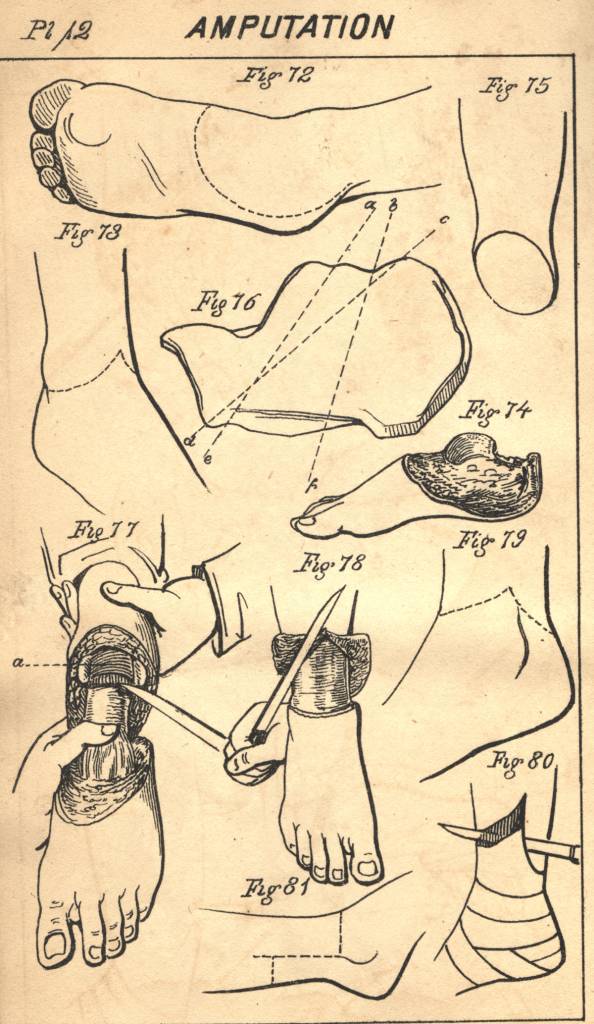

They had two main ways of cutting off limbs: flap and circular amputations. The surgeons had to figure out how to deal with big limbs that needed to be removed, so they developed these methods. Flap amputations were more complicated. The surgeon had to be super careful and cut into the bone while creating flaps of muscle and skin to close up the wound after. They made a V-shaped cut, separated the bone, and put the flaps over it. This way was supposed to be better for healing and avoiding infection.

On the other hand, circular amputations were simpler. The surgeon would cut a circle around the limb, pull back the skin, and then chop through the bone. This way was less complicated, but it could leave the patient with a stump that looked worse and wouldn’t cover up the bone as much, which could cause healing problems and increase the risk of infection.

Aftermath of Amputations

The immediate consequences of amputation included severe pain, blood loss, and the risk of infection. In the long term, amputees faced challenges such as phantom limb pain, reduced mobility, and difficulty finding employment. Many also experienced psychological trauma due to the loss of their limb and the stigma associated with disability. Prosthetic limbs were available, but these provided limited mobility and often required significant adjustments for the wearer. Despite their limitations, prosthetic limbs offered some degree of independence and the ability to perform daily tasks for amputees.

Rehabilitation and Support for Amputees

Rehabilitation and support for amputees during the Civil War era were limited. While some soldiers received essential physical therapy, lacking specialized knowledge and resources often meant that many had to rely on family members and community support to adjust to their new circumstances. Additionally, organizations such as the United States Sanitary Commission and the United States Christian Commission provided aid and assistance to injured soldiers

during and after the war.

The high frequency of amputations during the Civil War spurred medical procedures and equipment innovations. The need for efficient and effective amputations led to the development of specialized surgical tools and techniques. Additionally, the war highlighted the importance of antiseptic practices and paved the way for the widespread adoption of germ theory in medical practice.

The large number of amputees resulting from the Civil War forced society to confront the issue of disability on a broader scale. While stigma and discrimination against amputees persisted, the sheer number of disabled veterans led to a greater awareness of their needs and challenges. This awareness contributed to developing policies and programs to support disabled veterans and their families, such as establishing the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1865. Many amputees faced physical, emotional, and financial challenges, with some struggling to find employment and support themselves and their families. Losing a limb often significantly changes the individual’s role within the family and community, necessitating adaptations and support from loved ones.

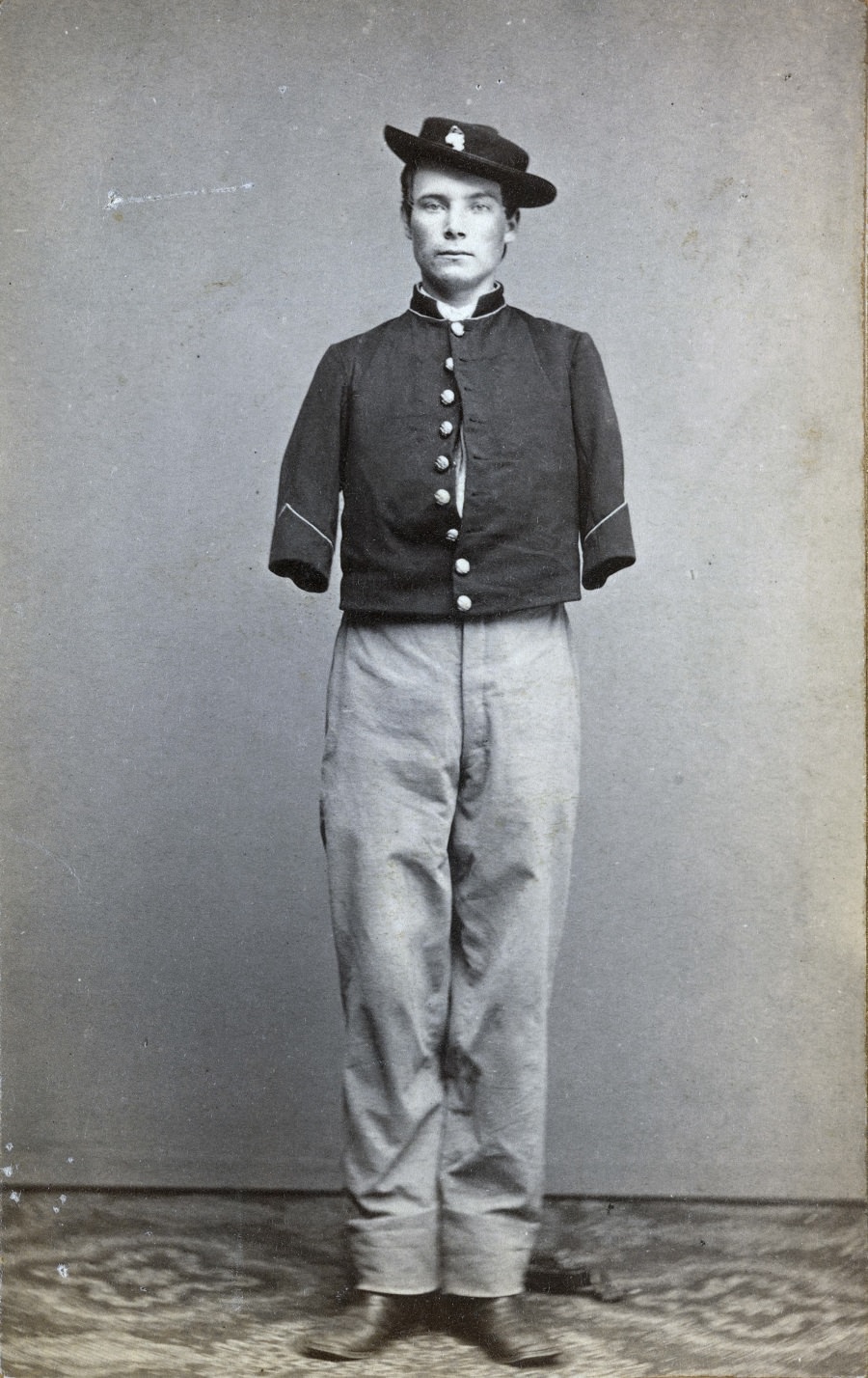

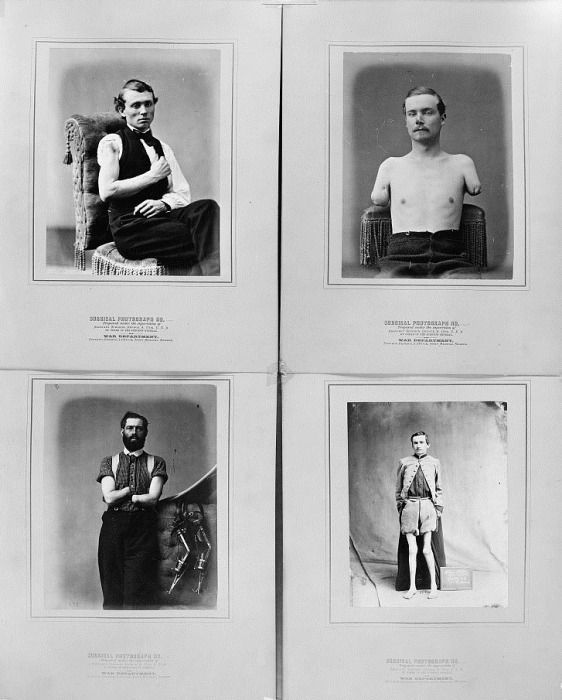

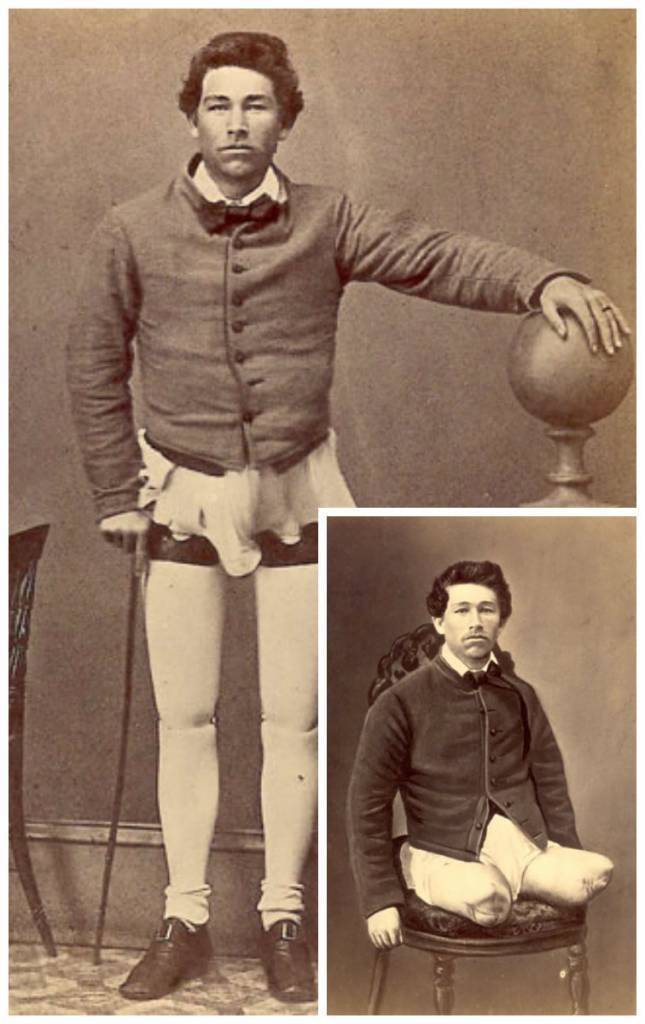

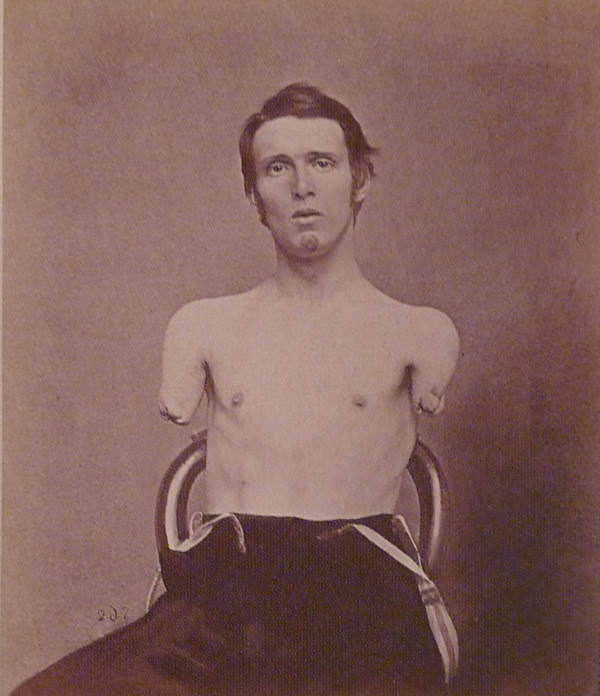

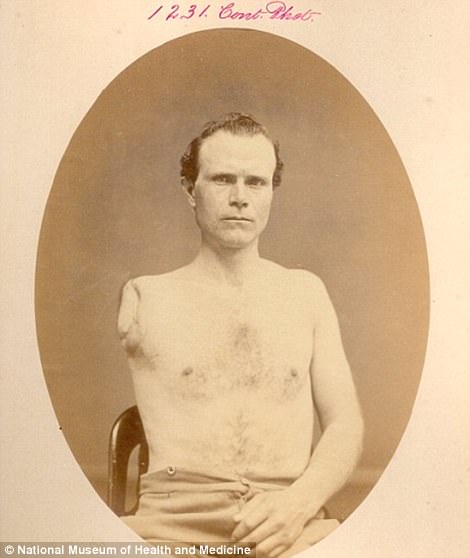

#1 Private William Sergent of Co. E, 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, in uniform, after the amputation of both arms. 1861.

He faced a life-altering challenge during the American Civil War when he underwent the amputation of both his arms. The exact circumstances surrounding his injuries are not detailed, but the double amputation suggests that he suffered severe wounds, likely from combat in the early years of the war, around 1861. Despite the profound physical impact of losing both arms, Sergent's photograph in uniform following his surgery represents his unwavering dedication to his regiment and the cause he fought for. His resilience in the face of adversity is emblematic of the determination and spirit of many soldiers during the Civil War. The medical treatments of the era, while rudimentary compared to modern standards, allowed soldiers like Sergent to survive and adapt to their new reality after sustaining such significant injuries.

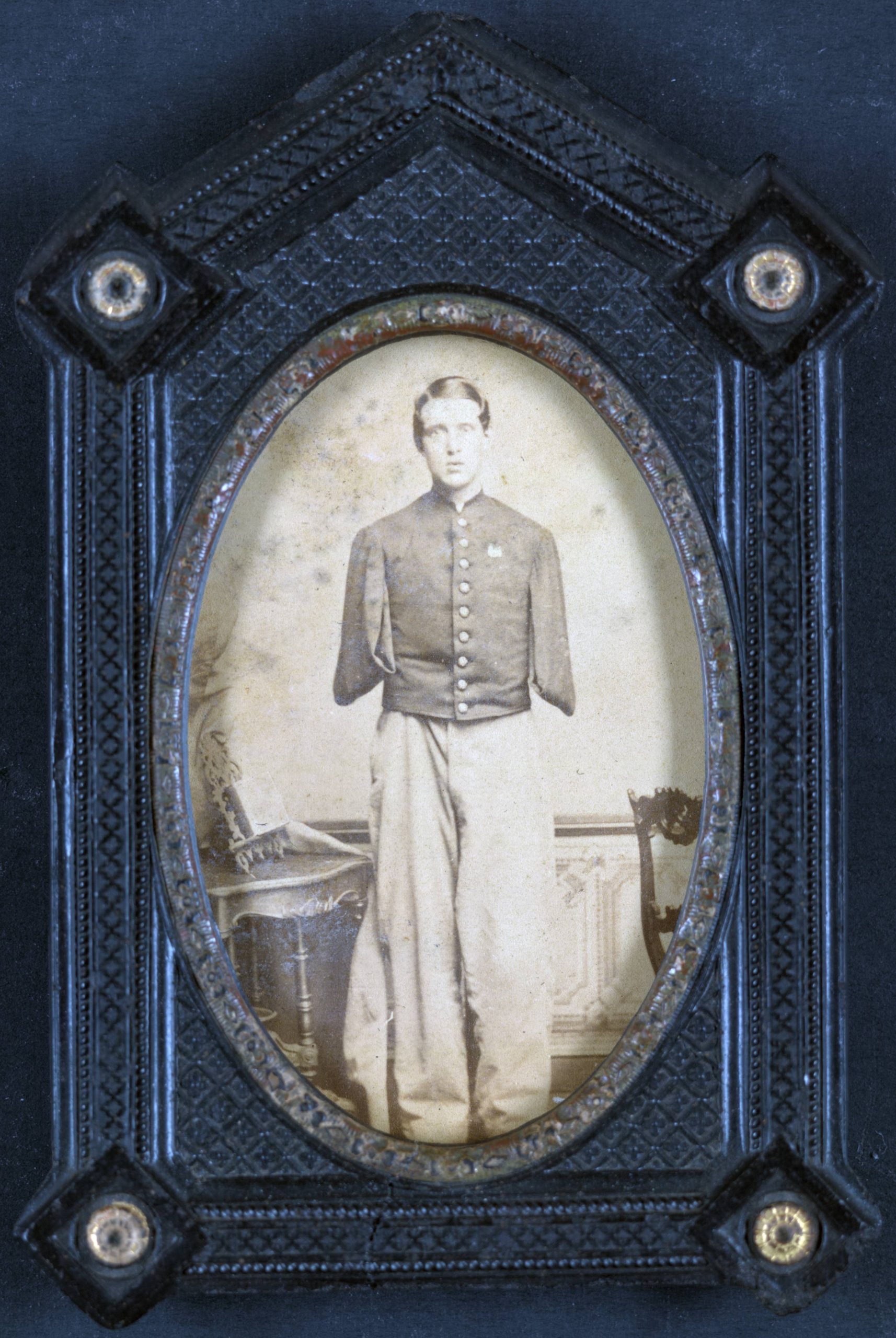

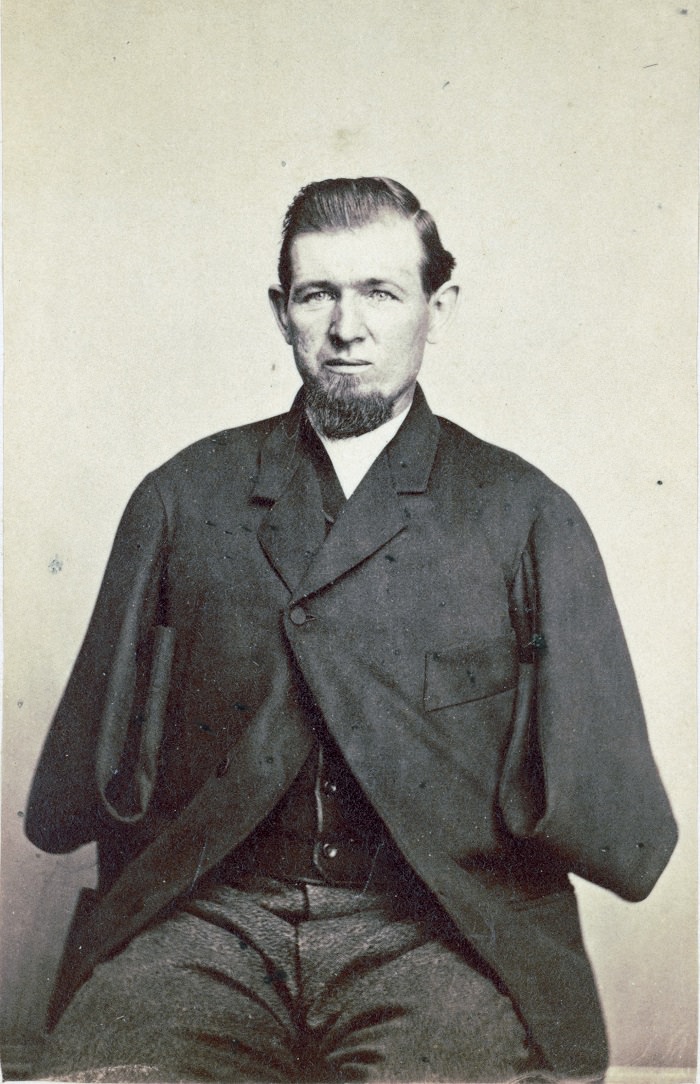

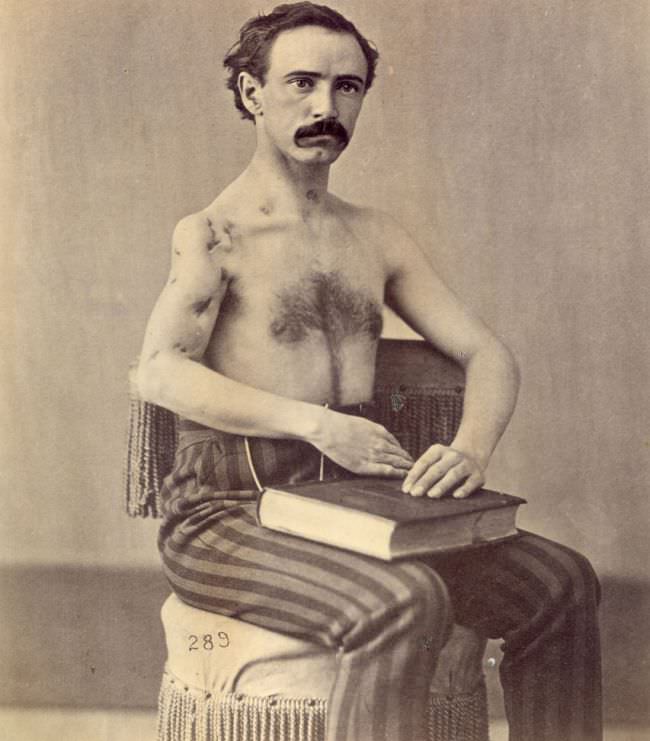

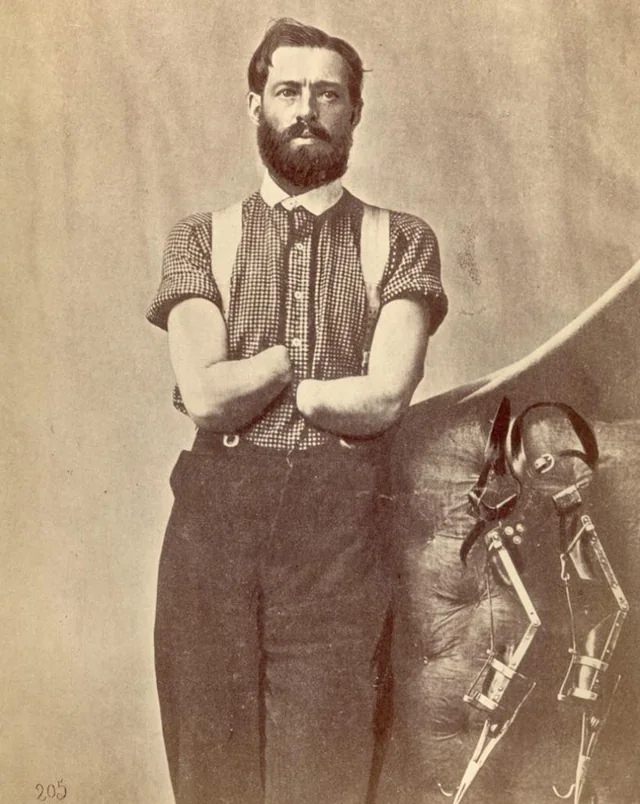

#2 Sergeant Alfred A. Stratton of Co. G, 147th New York Infantry Regiment, with amputated arms. 1864.

He suffered injuries that led to the amputation of both his arms in 1864. As a double amputee, Stratton demonstrated remarkable resilience and determination in the face of such life-altering circumstances.The medical procedures of the time, while rudimentary compared to today's standards, allowed soldiers like Stratton to survive severe injuries and continue their lives, albeit with significant physical limitations. It is a testament to the courage and spirit of Civil War soldiers, who were willing to make great sacrifices for their cause.

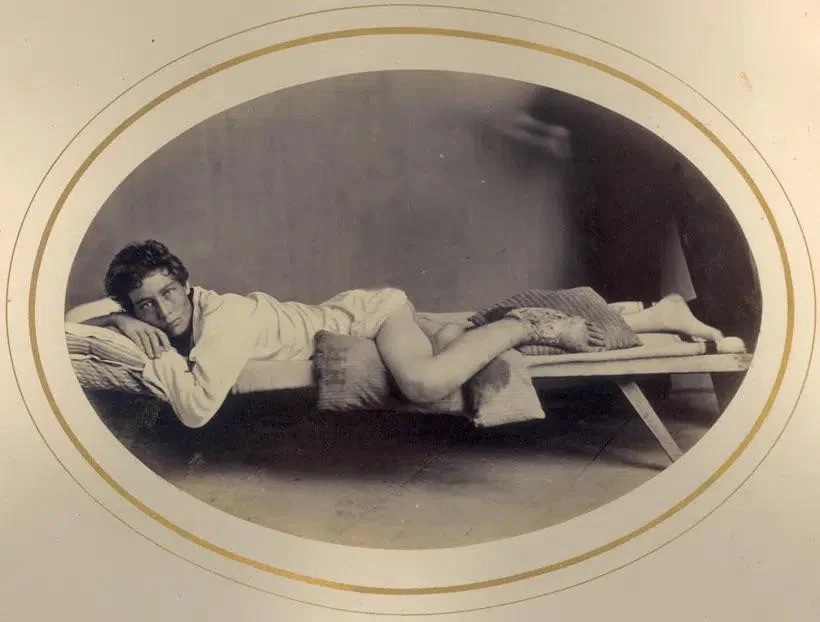

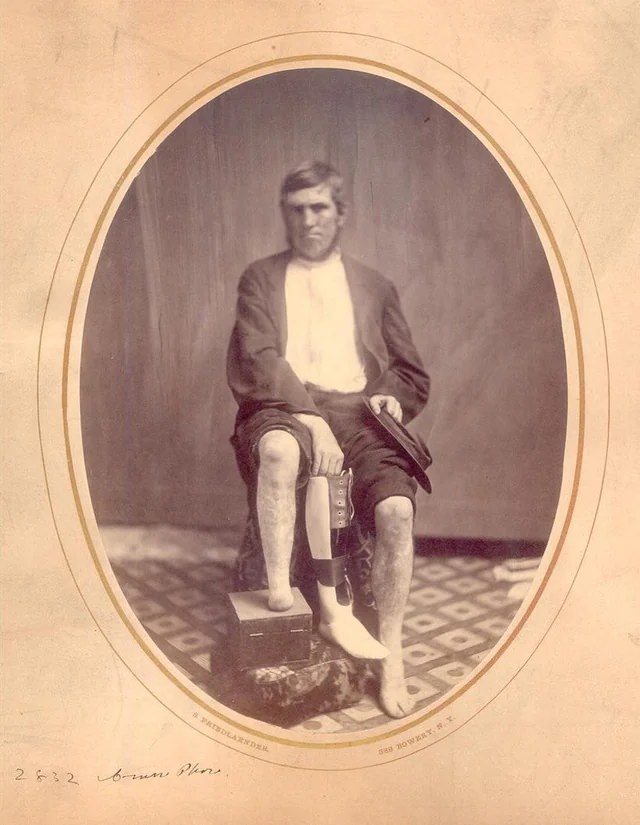

#3 Corporal Michael Dunn of Co. H, 46th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, after the amputation of his legs in 1864.

He faced significant challenges when he suffered injuries that required the amputation of both his legs in 1864. The exact circumstances surrounding the injuries are not provided, but it is likely that they occurred during combat.Following the amputations, Corporal Dunn faced substantial physical limitations and had to adapt to his new reality. The medical practices of the time, though less advanced than today's techniques, allowed soldiers like Dunn to survive such severe injuries. Dunn's resilience and determination were vital in coping with the physical and emotional challenges resulting from his amputations.

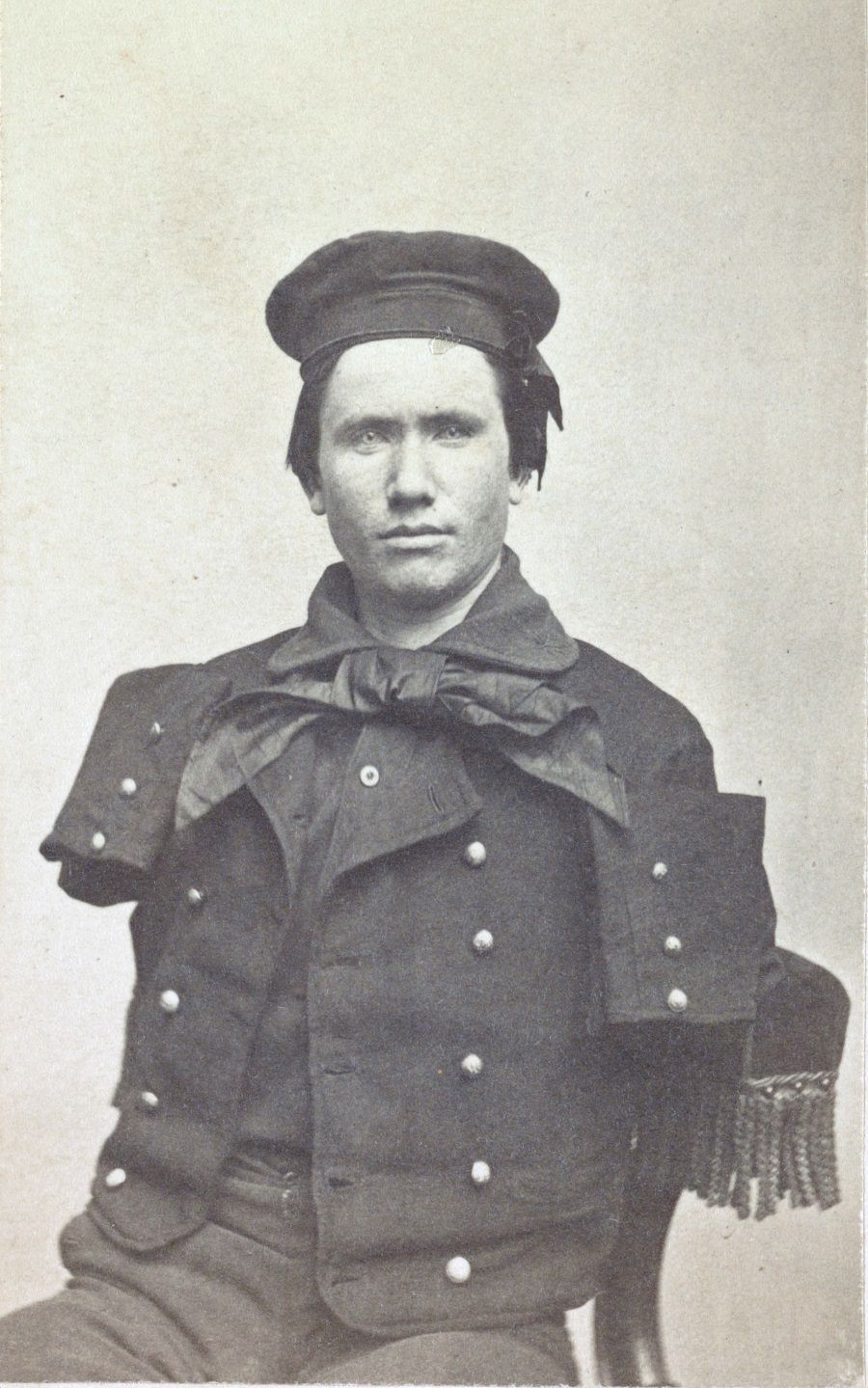

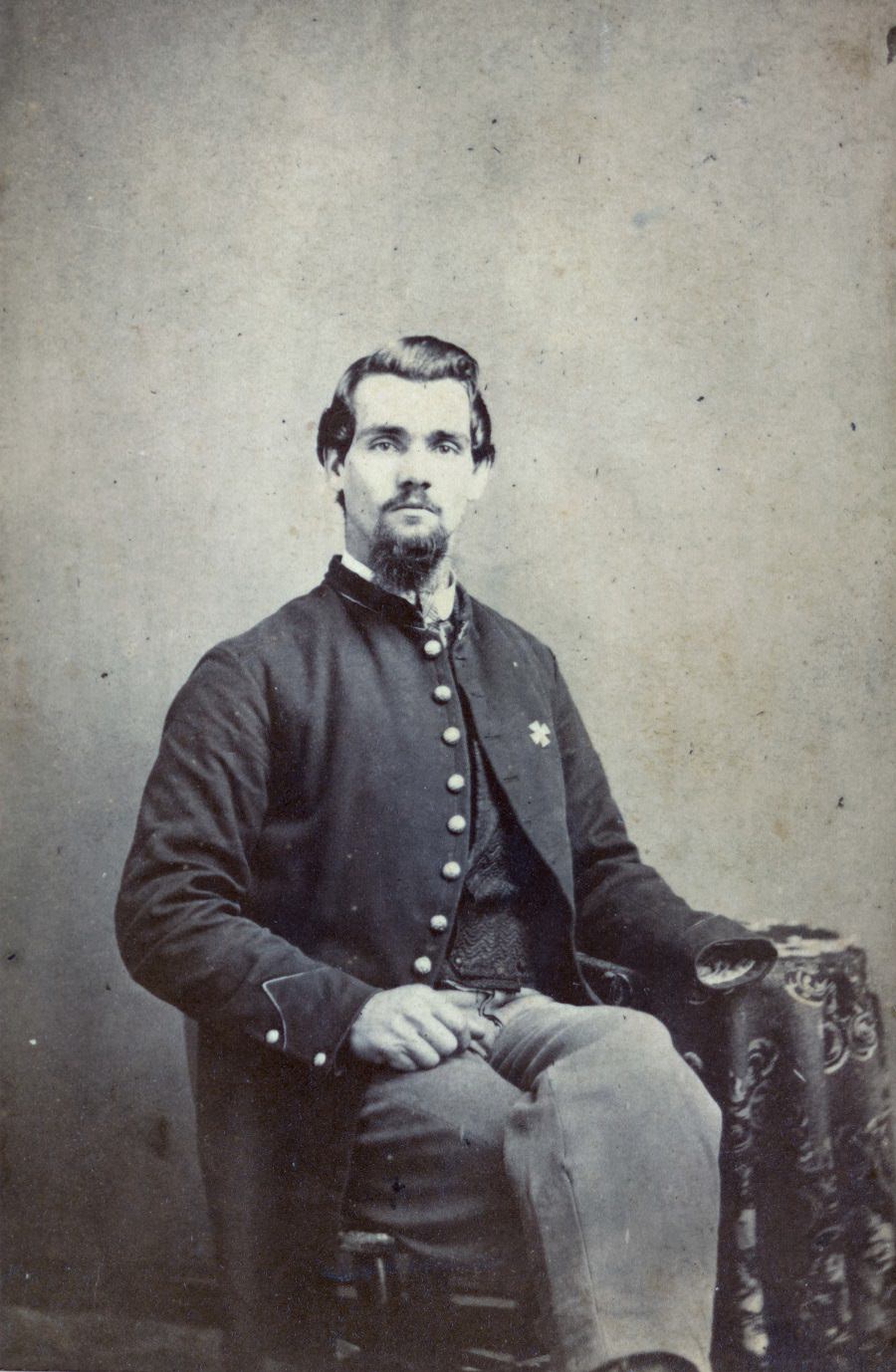

#4 Richard D. Dunphy, U.S. Navy coal heaver in uniform. 1864.

He served as a coal heaver in the U.S. Navy during the American Civil War. In 1864, Dunphy suffered serious injuries. Coal heavers like Dunphy played a vital role in maintaining the ships' steam engines by shoveling coal into the boilers. These laborers worked in difficult and dangerous conditions, with the constant risk of injury or even death.

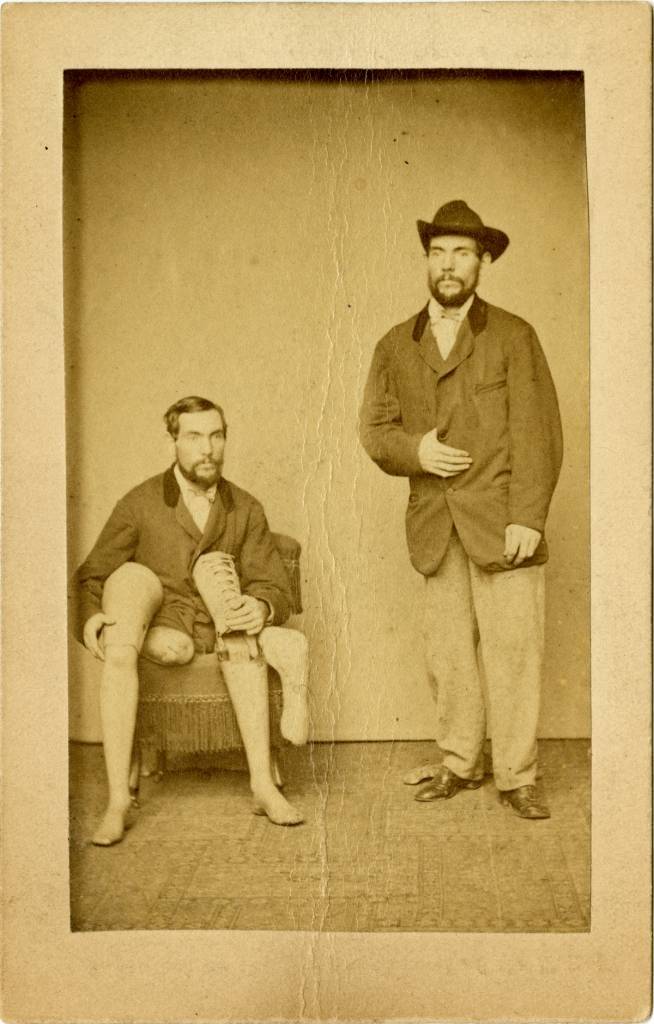

#5 John W. January, veteran of Co. B, 14th Illinois Cavalry Regiment, with prosthetic legs in 1890.

He served during the American Civil War. At some point during his service, he sustained injuries that led to the amputation of both his legs. The exact circumstances surrounding his injuries are not provided, but they likely occurred during a battle or an accident while on duty.By 1890, January had been fitted with prosthetic legs, which helped him regain mobility and independence in his daily life. Prosthetic technology during that time was still rudimentary compared to modern prosthetics, but it allowed amputees like January to adapt to their new reality and continue to be active members of society.

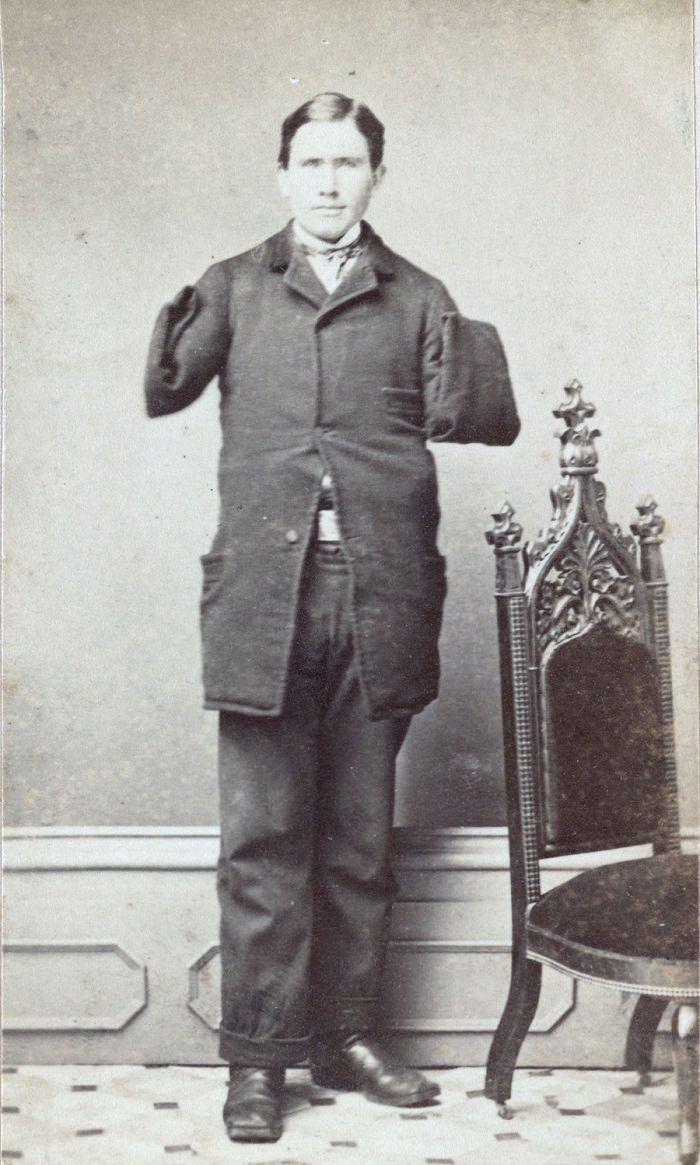

#6 Private Vernon Mosher of Co. F, 97th New York Infantry Regiment, in uniform, amputated hand visible, 1867.

He served in Company F of the 97th New York Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War. Unfortunately, the specific details about his experience or the circumstances surrounding his service are not available. Nevertheless, soldiers like Mosher played an essential role in the various engagements and campaigns throughout the war. The 97th New York Infantry Regiment, also known as the Conkling Rifles, was organized in Boonville, New York, in early 1862. They participated in numerous battles, including the Peninsula Campaign, the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Gettysburg, and the Battle of the Wilderness, among others. The regiment was involved in various campaigns and theaters of the war until they were mustered out in August 1865.As a member of the 97th New York Infantry Regiment, Private Mosher would have likely participated in some of these significant battles, facing the challenges and dangers of war.

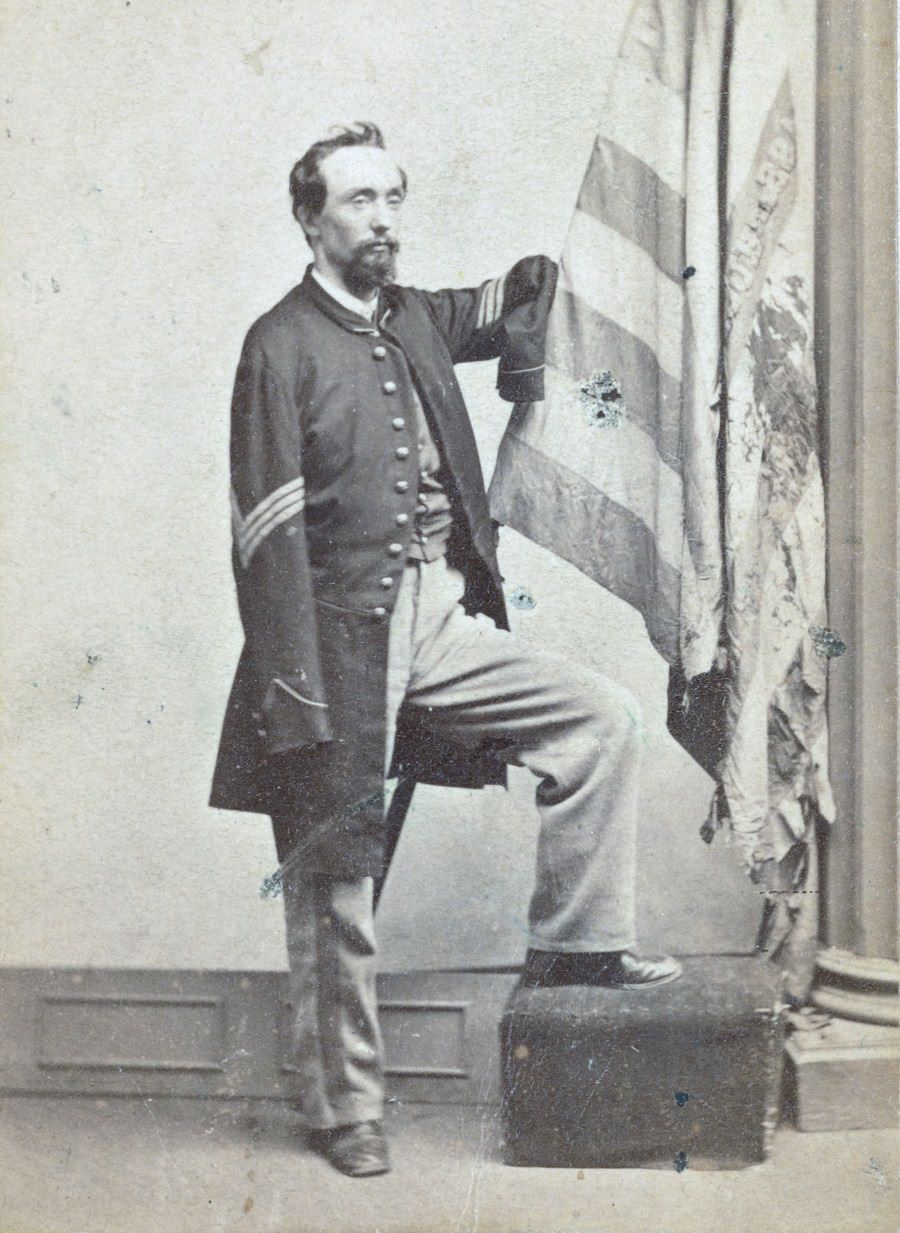

#7 Sergeant Thomas Plunkett of Co. E, 21st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in uniform with American flag, 1863.

Sergeant Thomas Plunkett served in Company E of the 21st Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War. He gained notoriety for his incredible act of bravery during the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. During the battle, a Confederate shell exploded near Sergeant Plunkett, causing severe injuries that ultimately led to the amputation of both his arms. Despite his injuries, Plunkett managed to save the flag of his regiment from falling into enemy hands by holding it against his body until help arrived. His actions were a testament to his commitment to his regiment and the Union cause.For his heroism, Plunkett was awarded the Medal of Honor on March 30, 1866. The citation for his medal recognized his courageous efforts in saving the regimental colors and highlighted his dedication to duty even in the face of severe personal injury.

#8 Private George W. Warner, wounded at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. Photographed in 1868.

Private George W. Warner served in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. The Battle of Gettysburg was one of the most crucial and deadliest engagements of the war, with over 50,000 casualties in just three days of fighting. While the specific details surrounding Private Warner's service, injuries, and recovery are not provided, it is evident that he, like many others, experienced the harsh realities of the battlefield. Soldiers who were wounded often faced long and painful recoveries, with many requiring amputations or suffering from lingering health issues.

#9 Richard D. Dunphy, wounded in the Battle of Mobile Bay and awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, 1864.

Richard D. Dunphy was a coal heaver in the U.S. Navy during the American Civil War. He was severely wounded in the Battle of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864. The battle was a significant naval engagement in which Union Admiral David G. Farragut led his fleet to capture the Confederate-held Mobile Bay, a key Southern port. His injuries were severe enough to require the amputation of both arms.The citation for Dunphy's Medal of Honor praised his gallant conduct and devotion to duty during the battle.

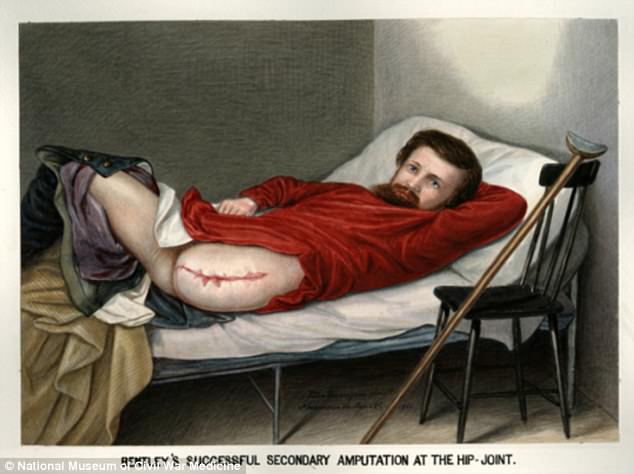

#10 Private George W. Lemon, who was shot in the leg at the 1864 Battle of the Wilderness 1864.

Heserved in the Union Army during the American Civil War and was shot in the leg during the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5-7, 1864. The battle, which took place in Virginia, was an intense and chaotic confrontation between Union General Ulysses S. Grant and Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The thick undergrowth and limited visibility in the Wilderness region made the fighting brutal, resulting in a high number of casualties on both sides. He was Captured by Confederates and treatment of his wounds was delayed and he suffered repeated infections. His leg was finally amputated.

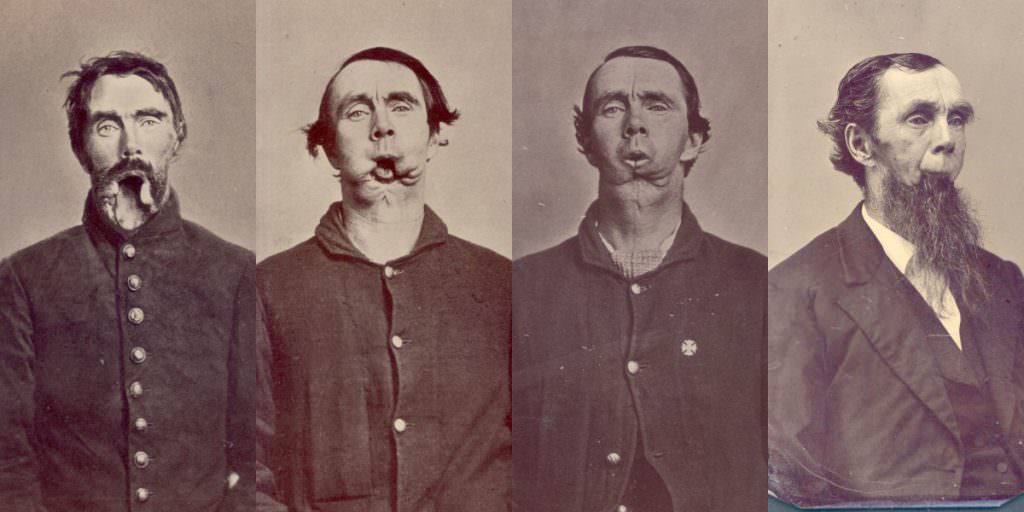

#11 Broken Faces of Warriors

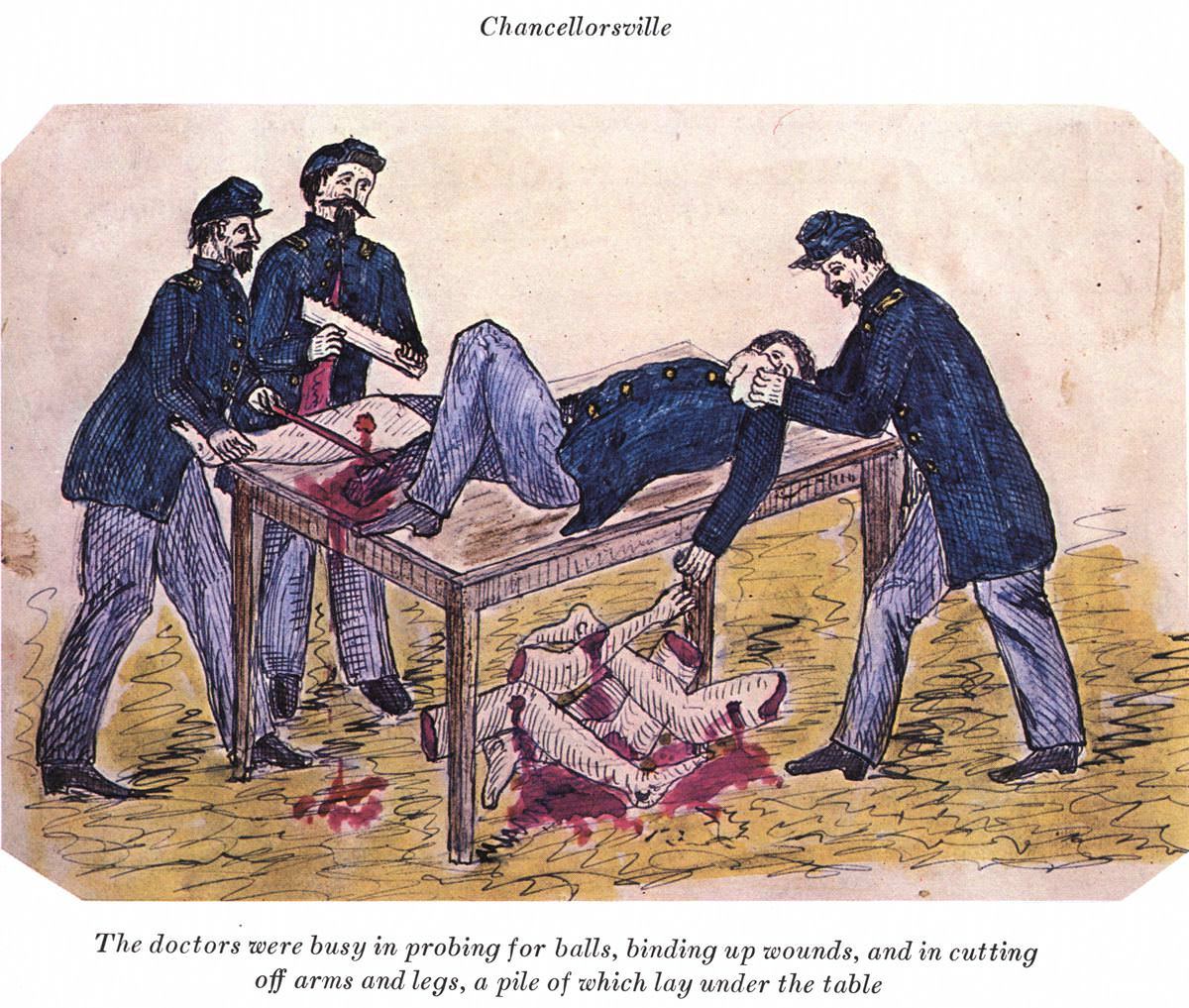

#12 Army doctors performing an amputation in a make-shift hospital during the U.S. Civil War (1861-65), 1863.

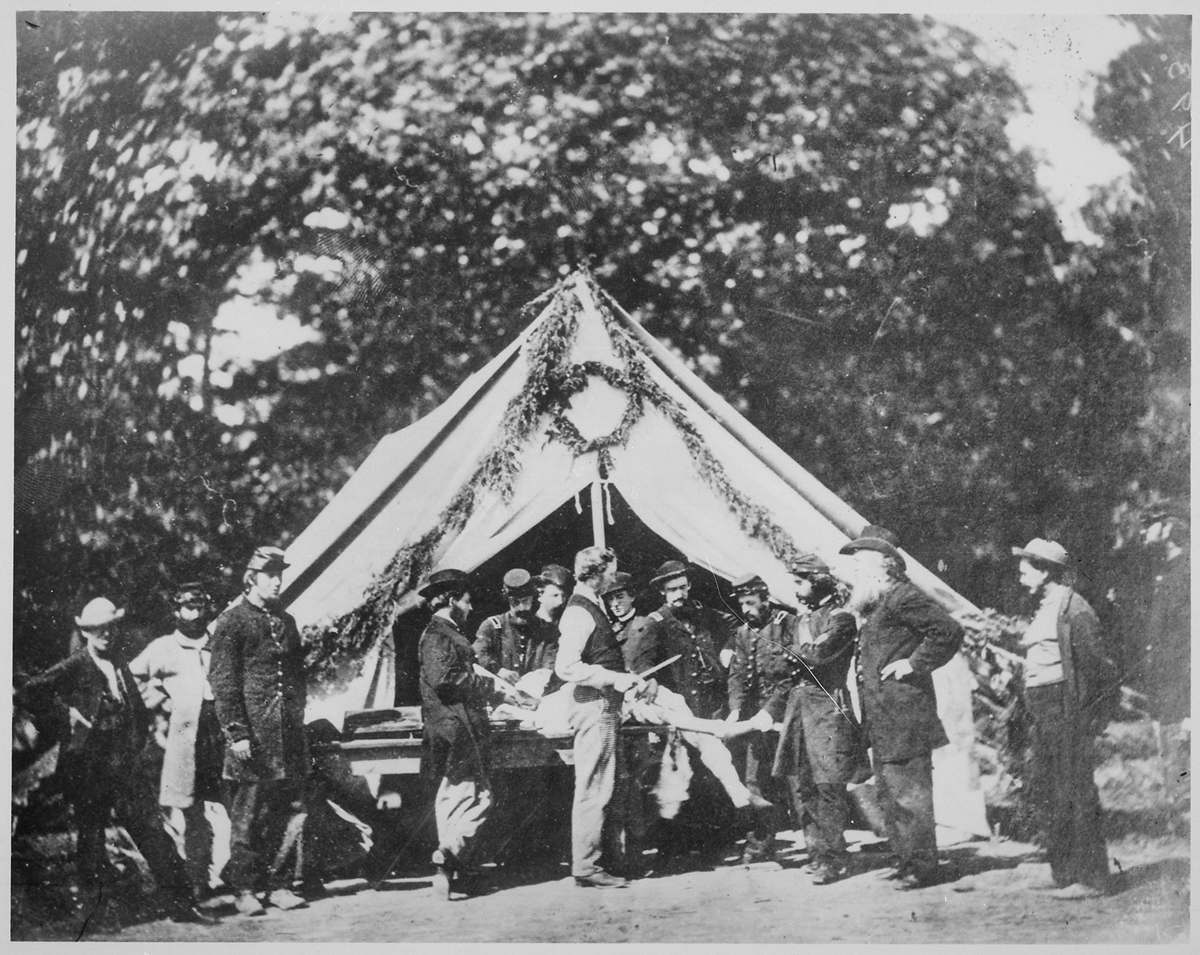

#13 Amputation being performed in front of a hospital tent, Gettysburg, July 1863

#14 This series of photographs, compiled by the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office, illustrates the different types of arm amputations.

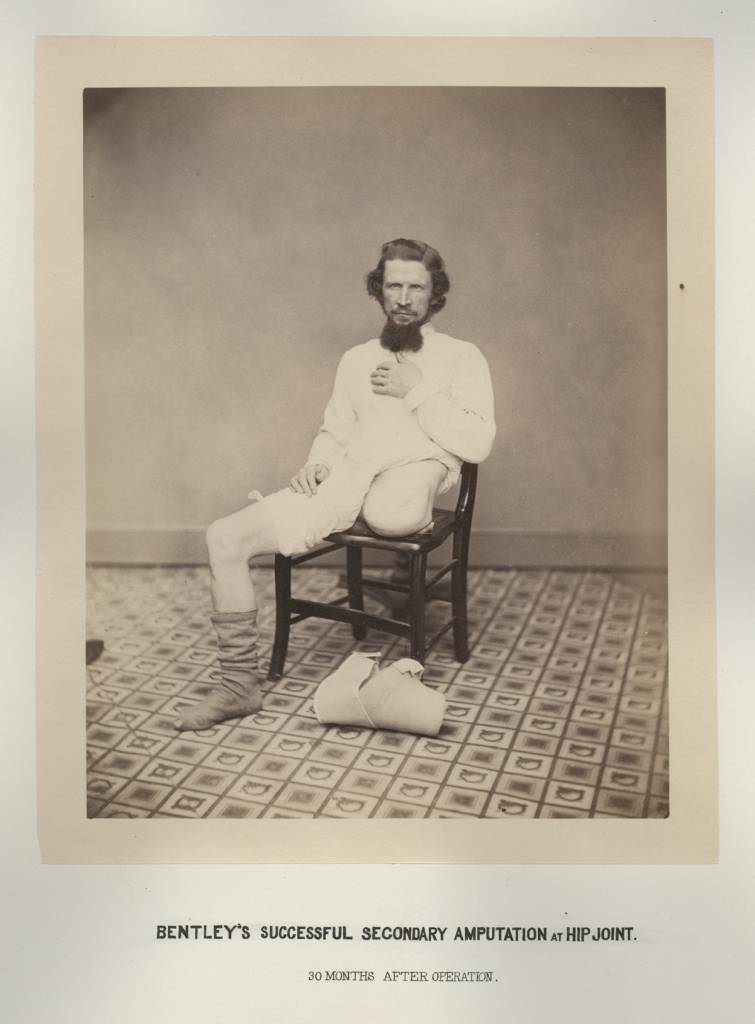

#15 Private George W. Lemon, from George A. Otis, Drawings, Photographs and Lithographs Illustrating the Histories of Seven Survivors of the Operation of Amputation at the Hipjoint, During the War of the Rebellion, Together with Abstracts of these Seven Successful Cases, 1867

Private George W. Lemon's story, as documented by George A. Otis, provides valuable insight into the experiences of soldiers during the American Civil War. Otis, an Assistant Surgeon in the Union Army and the curator of the Army Medical Museum, was responsible for collecting and preserving medical and surgical specimens, photographs, and case histories from the war. According to Otis, Private Lemon was shot in the leg during the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. Following his injury, it seems that Lemon faced considerable challenges in receiving proper medical care. As mentioned earlier, many soldiers faced delays in treatment, infections, and other complications, which sometimes led to amputations.

#16 Army Medical Wagon. Demonstration of the use of anesthesia in amputations.

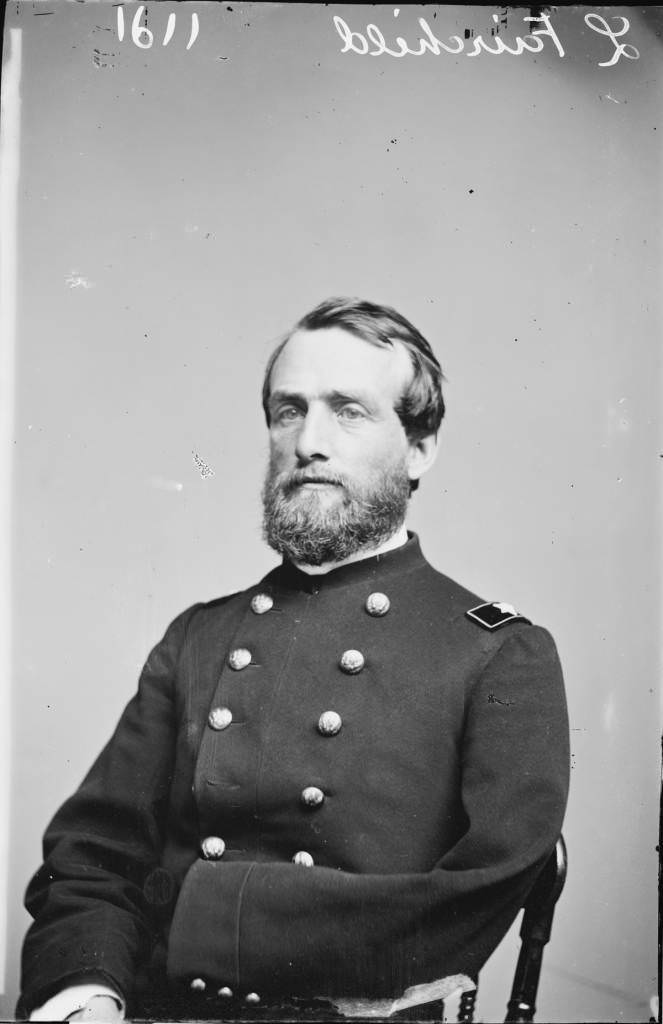

#17 Lucius Fairchild lost his left arm on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. He was elected Governor of Wisconsin in 1866.

He served as a Union Army officer during the American Civil War. He held the rank of Colonel when he was wounded on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863. The Battle of Gettysburg was a critical and deadly engagement that resulted in significant casualties on both sides. Fairchild's left arm was severely injured during the battle, and as a result, it had to be amputated. Despite this life-altering injury, he displayed remarkable resilience and continued to serve his country in various capacities after the war. After recovering from his wounds, Fairchild was promoted to Brigadier General and later Major General. He went on to have a successful political career, serving as the Secretary of State of Wisconsin, the Governor of Wisconsin for three terms, and the U.S. consul in Liverpool and Paris.

#18 Major General Daniel E. Sickles.

He was a prominent figure during the American Civil War, serving as a Union Army officer. Sickles had a colorful and controversial life, both before and after the war. His military career was marked by a combination of bravery, resilience, and at times, recklessness. During the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place from July 1 to 3, 1863, Sickles commanded the III Corps of the Army of the Potomac. On the second day of the battle, Sickles made a controversial decision to move his corps forward to occupy a higher ground, deviating from the defensive line planned by General George G. Meade. This move left his corps exposed and resulted in intense fighting. During the fighting on July 2, Sickles was severely wounded when a cannonball struck his right leg. He was evacuated from the battlefield, and his leg was amputated later that day. Despite the loss of his leg, Sickles remained active in military and political life. He was promoted to Major General after Gettysburg and continued to serve in the army until the end of the war. After the war, Sickles held several diplomatic posts, served as a U.S. Congressman, and was involved in veterans' organizations.

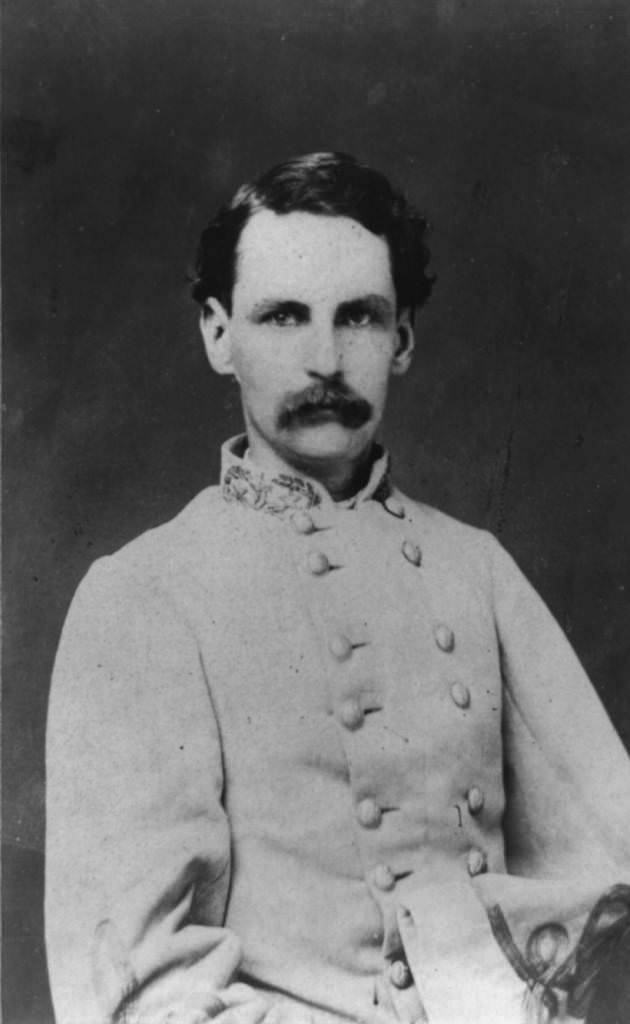

#19 Francis R. T. Nichols lost an arm and a foot in separate Civil War battles. He became Governor of Louisiana in 1877.

He was a Confederate soldier who served during the American Civil War, displaying remarkable resilience and determination. He lost an arm and a foot in separate battles, yet continued to serve his cause despite these life-altering injuries. Nichols began his military service as a Second Lieutenant in the 2nd Louisiana Infantry Regiment. In June 1862, during the Battle of Seven Pines (also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks) in Virginia, Nichols was severely wounded, leading to the amputation of his left arm. Despite this significant injury, he returned to active duty. In May 1864, Nichols faced another significant challenge during the Battle of the Wilderness, a fierce and bloody engagement in Virginia. During the battle, he sustained a severe injury to his right foot, necessitating its amputation. Remarkably, even after losing both an arm and a foot, Nichols persevered and continued to serve the Confederate cause. Eventually, he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General, becoming one of the youngest generals in the Confederate Army.

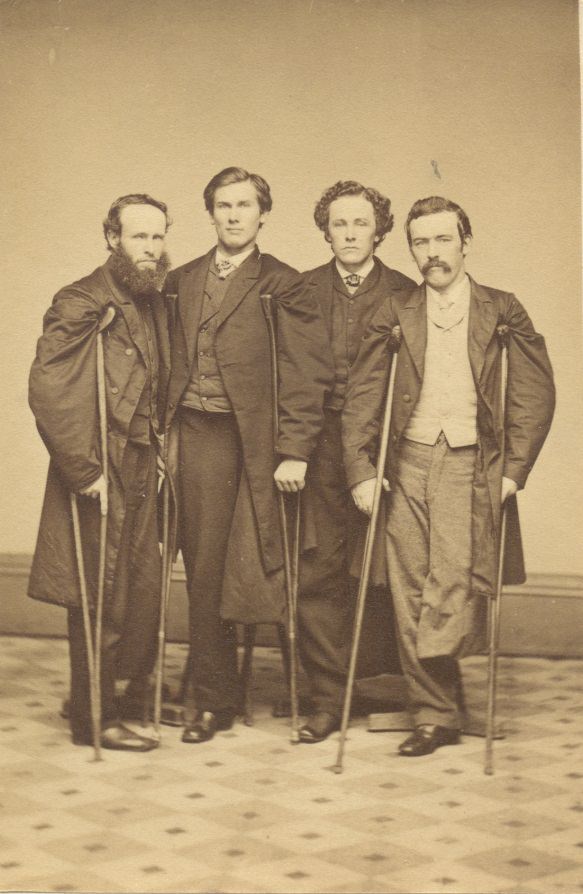

#20 Veterans John J. Long, Walter H. French, E. P. Robinson, and an unidentified companion, 1860s

John J. Long, Walter H. French, and E. P. Robinson were three veterans who served during the American Civil War. Long, French, and Robinson were among the countless men who demonstrated bravery and commitment to their respective causes during the war.

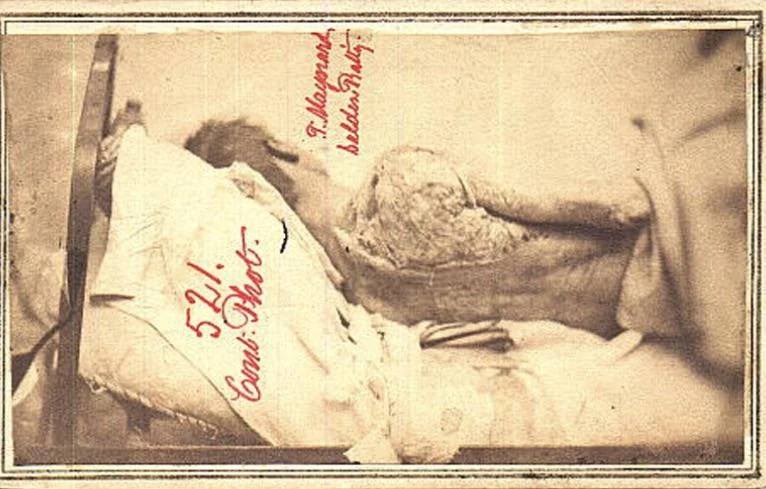

#21 Private Columbus Rush, Company C, 21st Georgia age 22, was wounded during the assault on Fort Stedman, Virginia, on March 25, 1865 by a shell fragment

Private Columbus Rush, a 22-year-old soldier from Company C of the 21st Georgia Infantry Regiment, was wounded during the assault on Fort Stedman, Virginia, on March 25, 1865. Fort Stedman was a crucial Union-held fortification near Petersburg, and the battle was part of the Confederate Army's desperate attempt to break the Union's stranglehold on the city. Rush was struck by a shell fragment during the battle, which caused a severe injury. Soldiers during the American Civil War faced a high risk of injury from various types of weaponry, including artillery shells. These fragments could cause significant damage to the human body, often leading to severe pain, disability, or even death. The Battle of Fort Stedman was one of the last major engagements of the Civil War, as the Confederate forces were eventually forced to abandon Petersburg and Richmond, leading to their ultimate surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

#22 A. A. Marks advertising card, showing a customer holding and wearing his artificial legs.

#23 On June 18, 1864, a cannon shot took both arms of Alfred Stratton. He was just 19 years old.

Alfred Stratton was a young soldier who faced a devastating injury during the American Civil War. On June 18, 1864, at the age of 19, a cannon shot took both of Stratton's arms. Amputations were often the only viable treatment for severe injuries caused by bullets, shrapnel, or other war-related traumas. Surgeons on both sides of the conflict performed these procedures under challenging conditions, often with limited medical supplies and equipment. The risk of infection and other complications was high, and recovery was difficult for many soldiers.

#24 Private. James P. whose humerus bone was fractured froma gunshot and removed.

James P. Kegerreis, Battery B, 2nd Pennsylvania Battalion Heavy Artillery, was wounded at Petersburg, Va., on June 17, 1864, by a conoidal ball (type of soft lead bullet), which entered just below the thyroid cartilage and to the left of the trachea, passed a little downward and to the right under the jugular vein, carrying away one of the wings of the trachea and emerging about a half-inch above the clavicle, was deflected in its course by hitting the butt of the musket and again entered in front of the right clavicle.

#25 Private Lewis Francis, Co. I, 14th New York Militia, was wounded July 21, 1861, at the first battle of Bull Run by a bayonet to the knee. He was stabbed at least 14 more times. He died May 31, 1874.

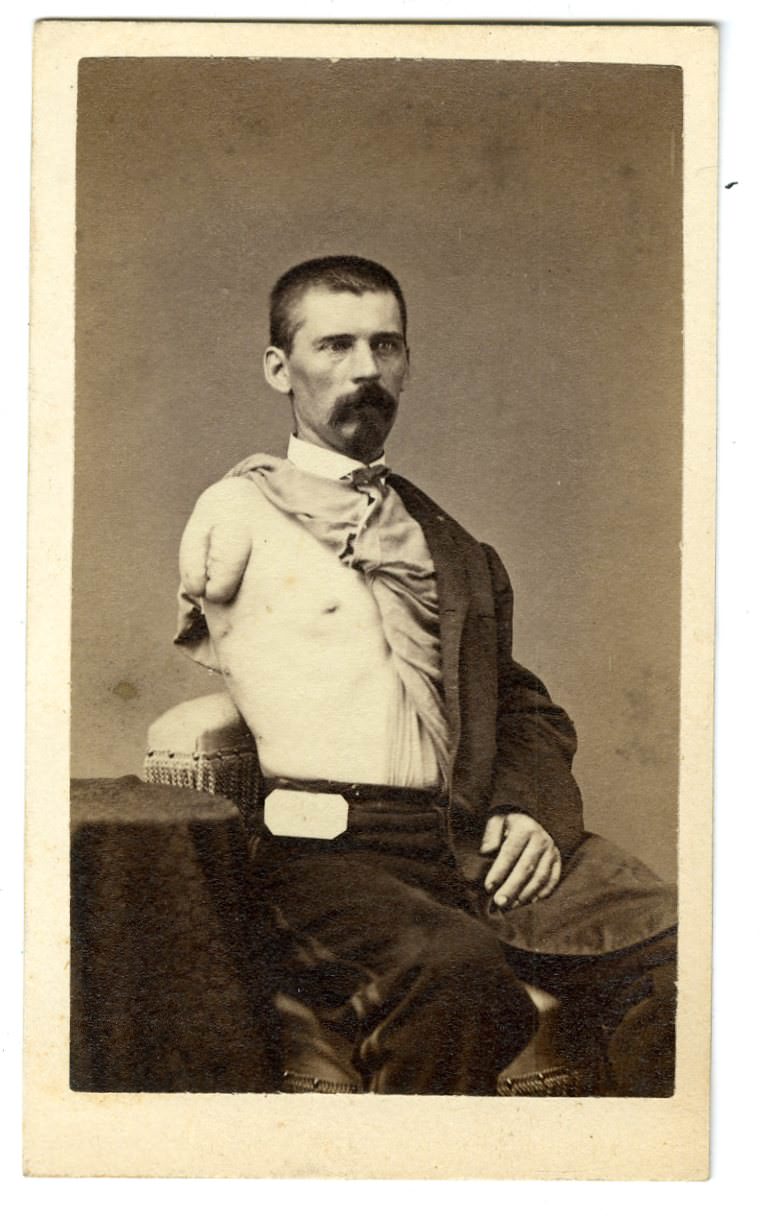

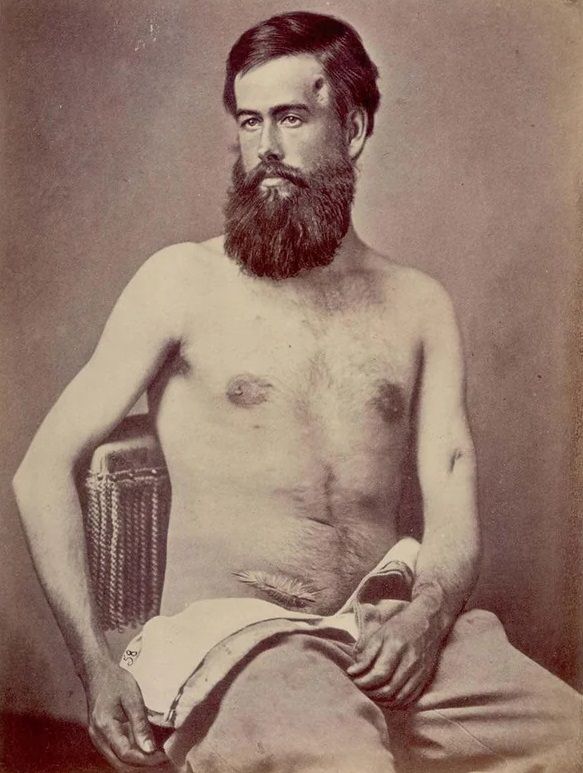

#26 Major General Henry Barnum shows off his war wounds. Barnum was shot through the side in 1862 and later received a Medal of Honor for his leadership.

He was shot through the side in 1862, sustaining a severe injury that left a lasting impact. Barnum's leadership and bravery during the war earned him the Medal of Honor, the United States' highest military award for valor. The Medal of Honor is presented to those who demonstrate exceptional gallantry and selflessness in the face of danger, often risking their lives for the sake of their fellow soldiers and their country.

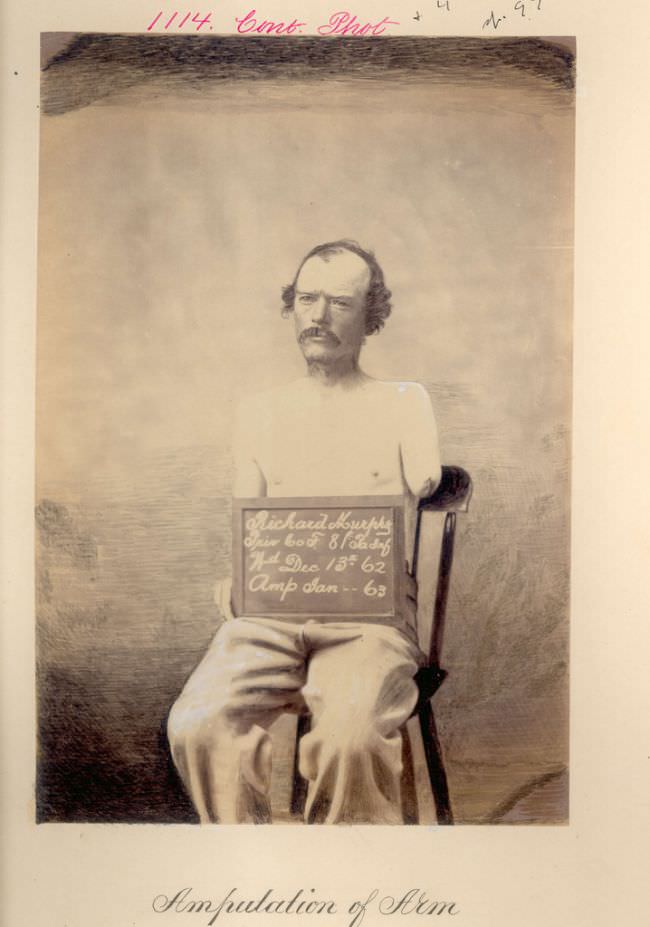

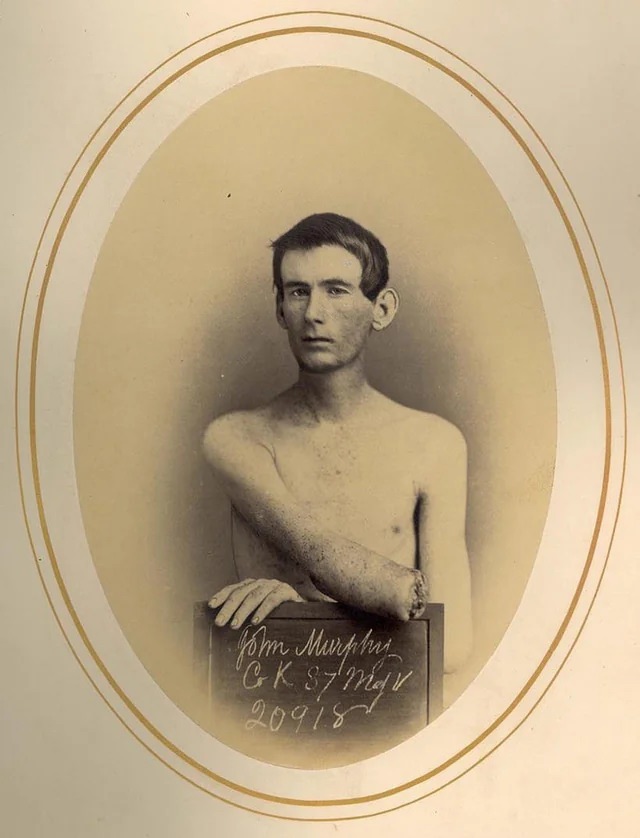

#27 Pennsylvania infantryman Richard Murphy was wounded in December 1862. Surgeons amputated his arm shortly thereafter.

He was wounded during the American Civil War in December 1862. His injury occurred at a time when the war was increasingly brutal and marked by significant casualties on both sides. Like many soldiers, Murphy faced the dangers of the battlefield and experienced the harsh realities of war.

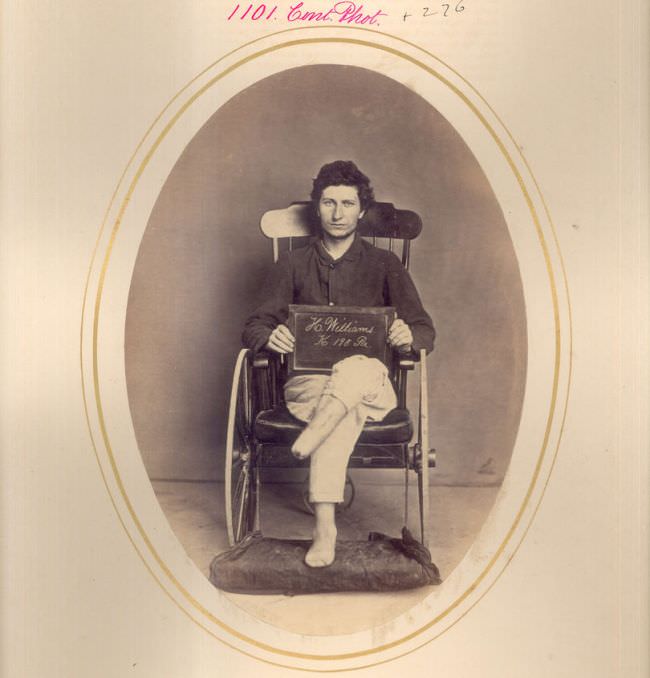

#28 Hiram Williams had his leg and foot amputated due to a shell wound in the Battle of Appomattox in 1865.

He sustained a severe shell wound during the Battle of Appomattox in 1865. This injury resulted in the amputation of his leg and foot, a life-altering event that was, unfortunately, all too common for soldiers in that conflict.

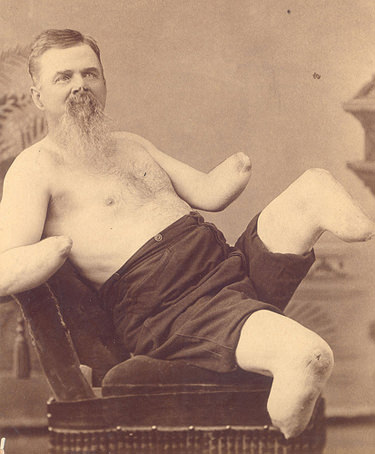

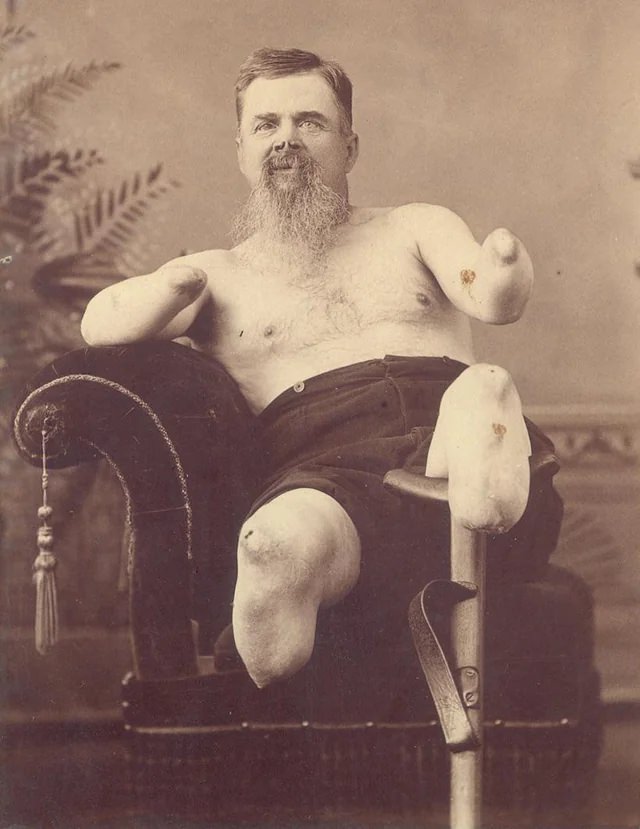

#29 A man who lost all of his limbs during a battle but he still managed to look cheeky for the camera.

#30 Soldier recovering from surgery after being amputated.

#31 Pile of severed, amputated arms and legs in an undated photo.

#32 Hiram Williams. Amputation of leg and foot, shell wound. PVT, Company K, 98th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Injured at the 1865 Battle of Appomattox

He was a Private in Company K of the 98th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the American Civil War. He suffered a devastating shell wound that led to the amputation of his leg and foot. This type of injury was common during the war, as the use of artillery and other heavy weaponry caused severe damage to soldiers on the battlefield. The 98th Pennsylvania Volunteers were involved in numerous engagements throughout the war, participating in some of the most significant battles, such as Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. The unit faced substantial danger and hardship, and soldiers like Hiram Williams paid a high price for their service. Amputations were a frequent occurrence during the Civil War due to the limited medical knowledge and resources available at the time. Surgeons often resorted to amputation as the primary treatment for severe limb injuries to prevent infection and save the soldier's life. Recovery was challenging for amputees like Williams, who had to adapt to life with a disability and the loss of a limb.

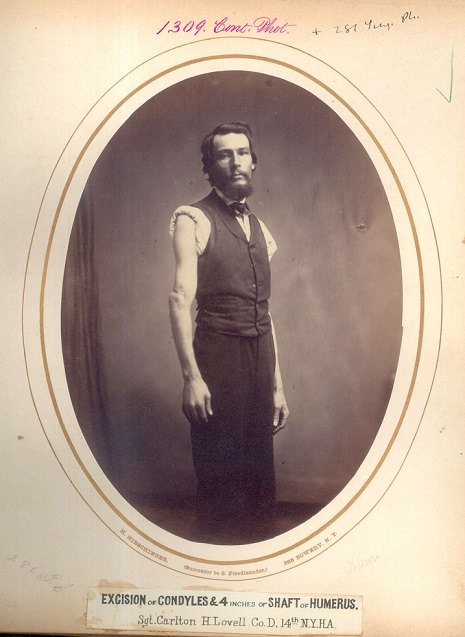

#33 Sgt. Carlton H. Lovell, 14th New York Heavy Artillery. Wounded June 2, 1864 at the Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia.

He fought in the American Civil War as a member of the 14th New York Heavy Artillery. On June 2, 1864, he was wounded during the Battle of Cold Harbor in Virginia.The Battle of Cold Harbor was a major engagement of the Civil War, fought between May 31 and June 12, 1864. The Union Army, led by General Ulysses S. Grant, suffered heavy losses in this battle, with over 7,000 casualties in just one hour on June 3. Sgt. Lovell was one of those casualties, wounded during the fierce fighting.

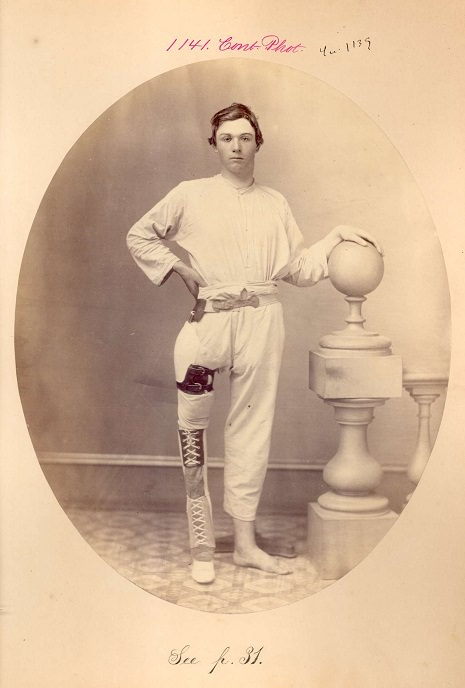

#34 Jason W. Joslyn. Excision of head & 4 inches of shaft femur, prosthesis in place. PVT, Company I, 7th New York Heavy Artillery. Injured at 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor

He was a private in Company I of the 7th New York Heavy Artillery during the American Civil War. He was injured during the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor, where he underwent a major surgical procedure known as excision of the head and 4 inches of the shaft of the femur. This procedure involved the removal of a portion of the femur bone in the thigh, typically due to severe injury or disease. In some cases, a prosthesis could be implanted to replace the missing bone, allowing the patient to regain some mobility and function.The 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor was a significant and bloody engagement of the Civil War, with thousands of casualties on both sides. J

#35 Sergeant Hector Sears from the Ohio Volunteers, was another to have six inches of his humerus removed

He was a soldier from Ohio who served in the American Civil War as a member of the Ohio Volunteers. During his service, he suffered a serious injury that resulted in the surgical removal of six inches of his humerus bone in his upper arm. After the surgery, Sergeant Sears required extensive medical attention and rehabilitation. He may have been fitted with a prosthesis or brace to help support his arm and shoulder

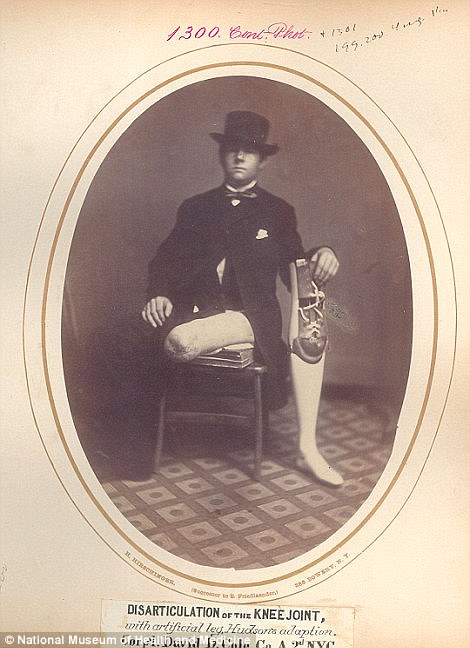

#36 Captain David D. Cole shows a stump where his leg was amputated following a complete separation of the knee joint at the Battle of Amelia Courthouse.

He was a soldier who fought in the American Civil War, and he suffered a severe injury during the Battle of Amelia Courthouse. During the battle, he suffered a complete separation of the knee joint, which required the amputation of his leg.

#37 Samuel Irwin, of the 67th Pennsylvania Volunteers, had his right arm cut off at the shoulder joint

The 67th Pennsylvania Volunteers were part of the Union Army and saw action in several key engagements, including the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness. These battles were marked by intense fighting and high casualties on both sides.

#38 This large single-edged amputation knife was used to cut through skin and muscle in circular amputations

#39 After skin and muscle had been were severed, this amputation saw – made with a steel blade and an ebony wooden handle – cut through bones

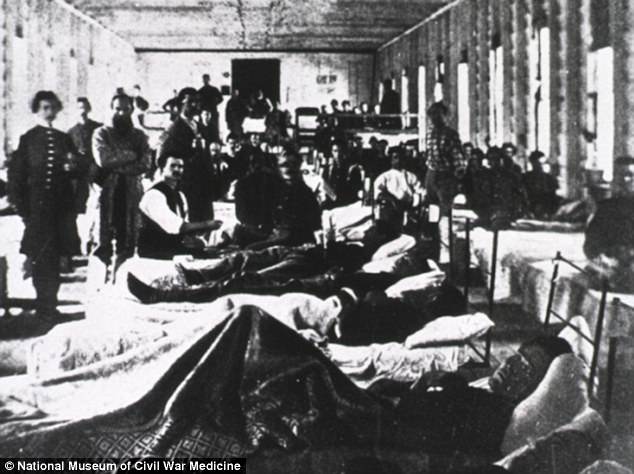

#40 A hospital ward in a convalescent camp in Alexandria, Virginia, pictured in the 1860s. In crowded camp conditions, infectious diseases spread rampantly and took more lives than battlefield injuries

#41 Surgeons carried around kits like this one, equipped with an amputation saw, knives, forceps and other surgical equipment

#42 This instrument is called a tooth key and was used for pulling teeth

#43 This prosthetic leg made of wood is a full left leg, articulated at the knee, with a leather shoe covering the foot. It still retains some of the original flesh-colored paint.

#44 This instrument, a fleam, was used for bloodletting. The U-shaped blade is spring-loaded and activated by the trigger above it. The depth of the cut can be regulated by a screw at the base of the lever.

#45 Spiral tourniquets were used during amputations to stem bleeding. The cloth strap would be wrapped around the limb, and the metal screw tightened until the blood flow slowed.

#46 This is a wooden stethoscope – the flat end was placed on the patient’s back or chest and the cupped end is the ear-piece.

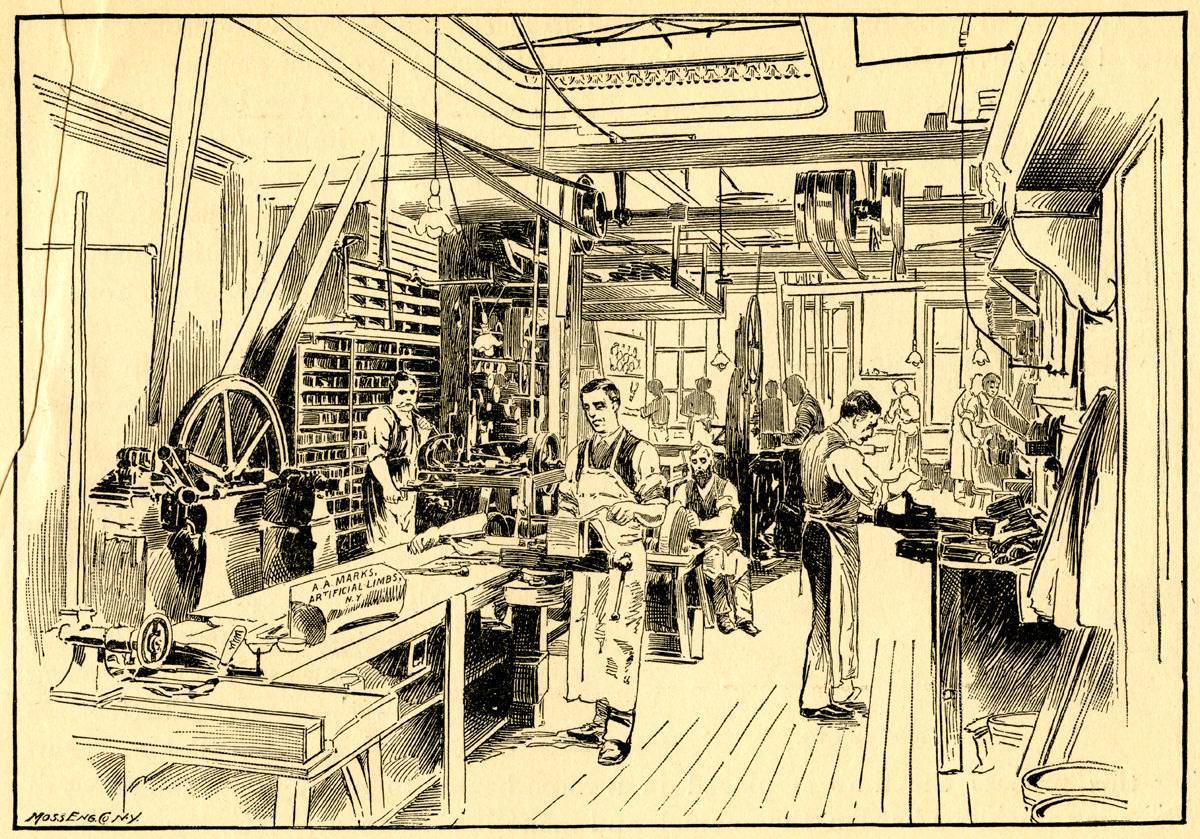

#47 This picture shows a prosthetics factory in the late 1800s. Almost 150 patents were issued for artificial limb designs between 1861 and 1873.

#48 A Manual of Military Surgery, Confederate States of America, Surgeon General’s Office, 1863

#49

#50 Pvt. Samuel H. Decker, Company I, 4th US artillery. Double amputation of the forearms for injury caused by the premature explosion of a gun on 8 October 1862, at the Battle of Perryville, KY. Shown with self-designed prosthetics.

He currently receives an annual pension of $300 and works as a doorkeeper at the House of Representatives. Thanks to his remarkable apparatus, he can write clearly, pick up small objects like pins, carry items of moderate weight, feed and dress himself, and even act as a formidable police officer in instances of disorder in the Congressional gallery. The 4th US Artillery was an important unit in the Union Army, providing artillery support in many of the major engagements of the Civil War. Their service and sacrifice, along with that of other soldiers during the conflict, helped to shape the course of American history and should be remembered and honored.

#51

#52

#53

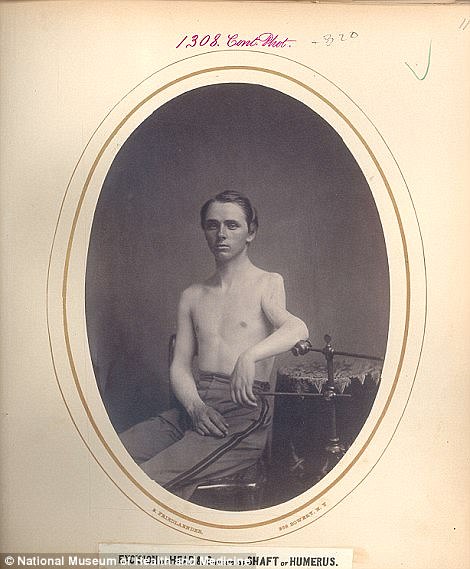

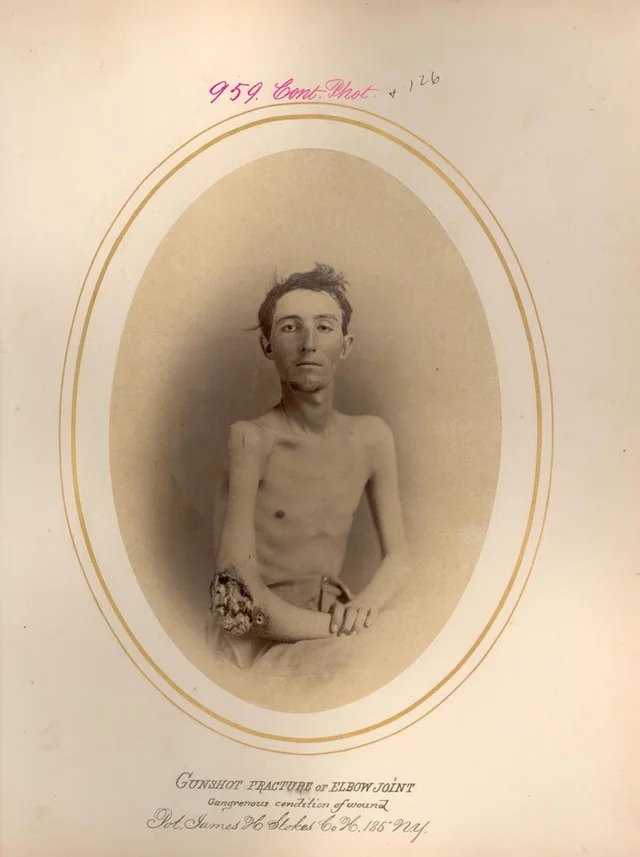

#54 James H. Stokes, Hospital Number 20,219, Private, Co. H, 185th N.Y. Vols., aged 20, a native of New York, was admitted to Harewood U.S.A. Gen’l Hospital, April 2nd, 1865 from City Point.

On March 29th, 1865, Stokes was struck by a Minie ball at Gravelly Run, Virginia. The bullet fractured his humerus and caused severe inflammation in his right forearm and elbow. was admitted to Harewood U.S.A. General Hospital on April 2nd, 1865, where he underwent surgery on his elbow joint. Unfortunately, gangrene set in by May 1st, which required further treatment with turpentine and kerosene oil. Stokes also received internal stimulants, iron chloride tincture, quinine, and a nutritious diet to aid in his recovery.Over the following months, his condition improved, and by June 1st, his arm was healing well. However, the injury ultimately resulted in anchylosis, or joint stiffness. Stokes was discharged on July 5th, 1865, after months of treatment under the care of Surgeon R.B. Bontecou. This story highlights the challenges faced by amputees during the Civil War, as well as the medical advancements and treatments of the time.

#55

#56 Private Edson D. Bemis, K, 12th Massachusetts, was wounded at Antietam by a musket ball, which fractured the shaft of his left humerus.

He was one of the 12th Massachusetts regiment was a resilient soldier who endured multiple injuries during the American Civil War. At Antietam, Bemis suffered a fractured left humerus due to a musket ball, which eventually healed with minimal displacement and shortening. After being promoted to corporal, he sustained another injury at the battle of the Wilderness, where a musket ball struck his right iliac fossa. Bemis underwent treatment at Chester Hospital near Philadelphia, experiencing extensive sloughing around the wound before it ultimately healed. Remarkably, Bemis returned to duty after eight months and was injured once more at Hatcher's Run near Petersburg. This time, a musket ball fractured his left temporal bone and lodged in his left cerebral hemisphere. Surgeons removed the ball and bone fragments on February 8, 1865. By July 15, 1865, the head wound was nearly healed, with only a slight discharge of pus remaining. Despite visible pulsations of the brain beneath the skin, Bemis retained full mental and sensory faculties. Corporal Bemis' remarkable survival and recovery from multiple severe injuries exemplify the resilience and determination of soldiers during the Civil War. His case can be found in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, providing insight into the surgical practices and treatments of the time.

#57

#58

#59

#60 James P. Kegerreis, Company B, 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery.

Private James P. Kegerreis, a soldier from Company B of the 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery, demonstrated an impressive recovery after suffering a complex gunshot injury during the Battle of Petersburg on June 17, 1864. A conoidal ball struck Kegerreis below the thyroid cartilage and to the left of the trachea, passing downward and to the right beneath the jugular vein. The bullet damaged a wing of the trachea before exiting above the clavicle, just three inches from the point of entrance. The trajectory of the bullet was altered when it struck the butt of Kegerreis' musket, re-entering his body in front of the right clavicle, two inches from the acromial end. It continued through the surgical neck of the humerus and exited near the center of the deltoid muscle. The severity of this injury required the excision of the humerus and involved damage to the trachea, clavicle, and shoulder joint. Despite the complexity of the wound, Private Kegerreis remarkably recovered from his injuries, showcasing the resilience of soldiers during the American Civil War and the surgical advancements made during this period.

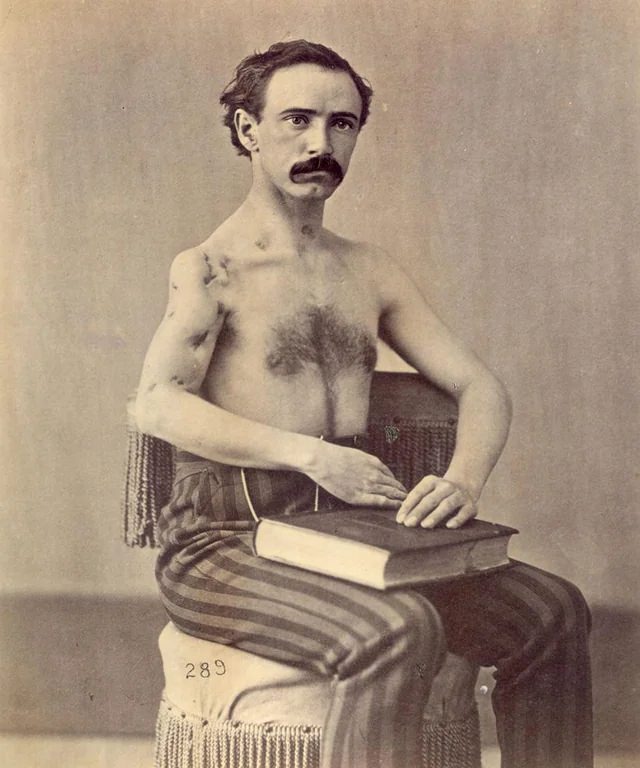

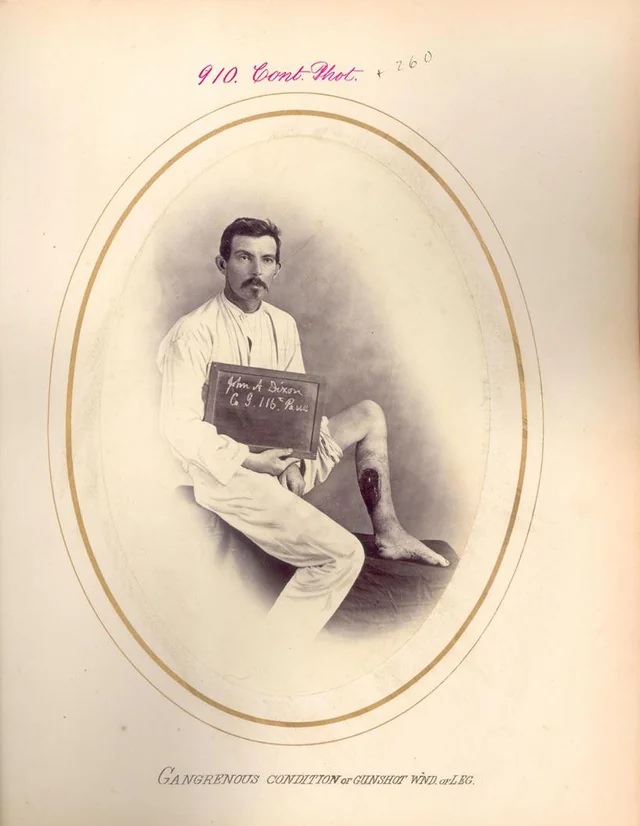

#61 John A. Dixon, Hospital Number 20,459, Serg’t, Co.

Sergeant John A. Dixon, a 32-year-old soldier from Company I, 116th Pennsylvania Volunteers, was admitted to Harewood U.S.A. General Hospital on April 12, 1865, after sustaining a gunshot wound to his left leg during the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia. The injury, which occurred on March 31, 1865, affected the lower third of his leg and caused damage to the soft tissues. Upon admission, both Dixon's overall health and the condition of his injured leg were considered good. His recovery progressed relatively smoothly until May 10, 1865, when gangrene developed in the affected area. Despite this complication, Dixon's outcome was ultimately favorable, and he began to heal under the care of Surgeon R.B. Bontecou, who was in charge of the hospital. Sergeant Dixon's case serves as another example of the resilience of Civil War soldiers and the medical treatments available at that time. Despite the challenges they faced, many soldiers managed to recover and heal from severe injuries, thanks tothe dedicated efforts of medical professionals.

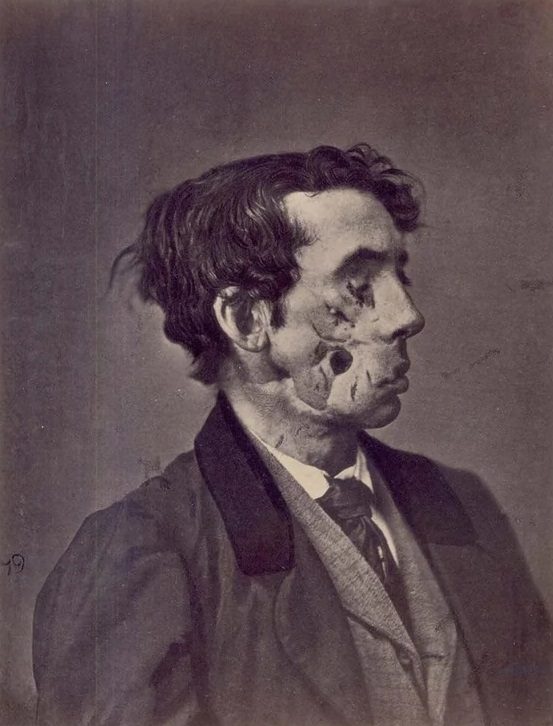

#62 Private Joseph Harvey, C, 149th New York, was wounded at the battle of Chancellorsville, May 3, 1863, by a fragment of shell.

Private Joseph Harvey of Company C, 149th New York, suffered severe injuries at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863. A fragment of a shell destroyed his right eye, fractured his right superior maxilla, chipped off a piece of his lower jaw, and extensively lacerated his right cheek. Harvey was captured by the enemy and remained a prisoner for 11 days. In June 1863, he was admitted to Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria. By August, exfoliated bone fragments were removed from his wounds. A ferrotype, a photograph-like image, captured the appearance of his injuries at that time and was sent to the Army Medical Museum. On May 7, 1865, Harvey was discharged from service due to physical disability but later found work as a night-watchman at the Commissary Hospital in Alexandria. When his photograph was taken on June 22, 1865, the loss of substance in Harvey's cheek remained unrepaired, causing liquids and saliva to escape from the wound. He also experienced slight deafness and partial facial paralysis on the right side. Harvey received a pension for his service-related injuries, but his death was reported on December 9, 1868, from an unknown cause. Private Harvey's case, documented by George A. Otis, is a testament to the resilience and determination of Civil War soldiers who endured life-altering injuries on the battlefield.

Anesthesia was not well understood at the time and was only mainstreamed in Britain 15-20 years before the Civil War. It was difficult to come by in the numbers needed to supply an army. Pain was not seen as a major issue in the 19th century. Surgeons were overworked and not well-trained. The best doctors from the East coast schools were reserved for desperate cases or to tend to wounded officers. Regimental infirmaries were staffed by an eclectic mix of enthusiasts, quacks, frauds, and med-school dropouts. In many cases, there were only 1-2 surgeons available to tend to thousands of wounded soldiers. Anesthesia might have made 1 person more comfortable but could cost the time needed to save 4 other lives, so it was not a priority for many surgeons.

Sadly, despite the use of anesthetics, many soldiers still died from infections after amputations during the Civil War. The reality of the time was that it was a dangerous and frightening time to be a soldier.

Morphine was extensively used during the Civil War, but addiction became a concern. Consequently, diamorphine was developed to help individuals transition off of morphine. However, that is a different story.

Then they created oxycodone to get people off the diamorphine.That, of course, is another story.

Yes, that’s correct. Morphine was commonly used as a pain reliever during the Civil War, but its addictive properties were not fully understood at the time. Many soldiers became addicted to the drug, and this addiction often continued long after the war was over. In 1874, a chemist named C.R. Wright synthesized diacetylmorphine, which was marketed by the Bayer pharmaceutical company as a non-addictive alternative to morphine. However, this new drug was soon found to be even more addictive than morphine and was eventually banned in the United States in 1924.

The anesthetics used during that time period were often imprecise and not held to the same quality standards as today.

Alcohol was the only available anesthetic at the time, and later on, there was a widespread addiction to morphine among soldiers that was referred to as “the soldier’s disease.”

If there were any anesthetics used during the Civil War, it was certainly not widespread or consistent. There is evidence to suggest that some alcohol was used as an anesthetic, but this is not a reliable or effective method. A book about the Napoleonic War describes how patients would sing during amputations and how severed limbs were thrown out of windows into piles. The same instruments were often used on multiple patients without proper sanitation. In one account, a soldier who made too much noise during surgery was hit with the arm that had just been amputated from another patient. The mindset of the time was very different from today, and it can be difficult to understand and imagine the experiences of those in the past.

Based on my understanding, the drug you may be referring to is chloroform. While it was used as an anesthetic during the Civil War, it was not always readily available and there were issues with its administration, including the risk of overdose and death. Additionally, many surgeons preferred to operate without anesthesia due to concerns about its safety and the potential for it to delay treatment. However, the use of anesthesia did increase during the war, and drugs like ether and chloroform were used when available.

In the film Gone with the Wind, the doctor discusses the shortage of anesthesia and the need to amputate a gangrenous leg regardless. Additionally, during this time period, there were issues with cleanliness as surgical tools were not always properly cleaned, and amputated limbs were often discarded outside the medical tents or buildings.

During my childhood in the 1950s, I was treated by a doctor who lived just three houses up the street and was in his 70s. He was a retired military physician and had written an important book on military surgery and treatment of war injuries. The book became the “bible” for military doctors and surgeons in the USA and Britain from 1916 onwards and was published in ten editions between 1916 and 1918.

Why was amputation so common during the Civil War?

The primary reason for the high number of amputations during the Civil War was the extensive use of large-caliber minie-ball ammunition, which caused severe and often irreparable damage to bones and soft tissue. In addition, the lack of antiseptics and antibiotics and the overwhelming number of patients made it difficult to perform extensive surgeries or attempt to repair the damage. As a result, amputations were often the only option for saving the lives of wounded soldiers.

During the Civil War, medical technology was not advanced enough to repair shattered bones and shredded blood vessels. The most effective way to save a soldier’s life was to remove the severely injured limb, as leaving it attached could lead to infection and death.

Amputation was a common medical practice before the Civil War because of the lack of advanced medical technology to repair severely damaged limbs. In cases where an artery was damaged, amputation was necessary to prevent the person from bleeding to death. This was also the case in previous times when medical technology was not advanced enough to repair damaged arteries.

Before the advent of antibiotics and germ theory, the only way to prevent gangrene was to amputate the affected limb. Additionally, a new type of bullet, the Minnie ball, caused more severe wounds.

The lack of sterilization and black powder muskets. Black powder muskets required a larger diameter bullet due to weak propellant, which caused extensive damage to bones and blood vessels that medicine at the time could not repair. Additionally, wounds left by the bullets required bandages, but with no knowledge of sterilization, the bandages were often reused after a light washing, causing infections that led to gangrene and amputation of the limb. The same contaminated bandages were then reused on the next patient, perpetuating the cycle of infections.

The expanding ammunition they used, like the Minnie ball, shattered bone on impact, unlike the old musket ball ammo that usually went clean through. Due to the extensive bone damage, amputation was often necessary, as there was no time or technology to repair it. Additionally, amputation was used to prevent infection, but unfortunately, the procedure itself often led to gangrene.

the lack of intravenous fluids and blood transfusions meant that hemorrhaging had to be stopped immediately to prevent death. Aseptic surgical techniques were not yet developed, leading to a higher incidence of wound infections. Additionally, general anesthesia had not been invented, so operations had to be performed quickly. Finally, the absence of antibiotics at the time meant that treatment options for infected wounds were limited. The first antibiotic, sulfanilimide, was not developed until 1936.

Many soldiers in photographs from this era appear to be very thin. Was this due to their injuries or was it common for soldiers to be thin during this time?

The soldiers during that time often suffered from malnutrition due to poor food provisions. In some cases, it was difficult to stay provisioned, which led to soldiers becoming extremely skinny. There were also issues with feeding POWs, which was a low priority and led to anger among Northerners regarding the South’s treatment of prisoners.