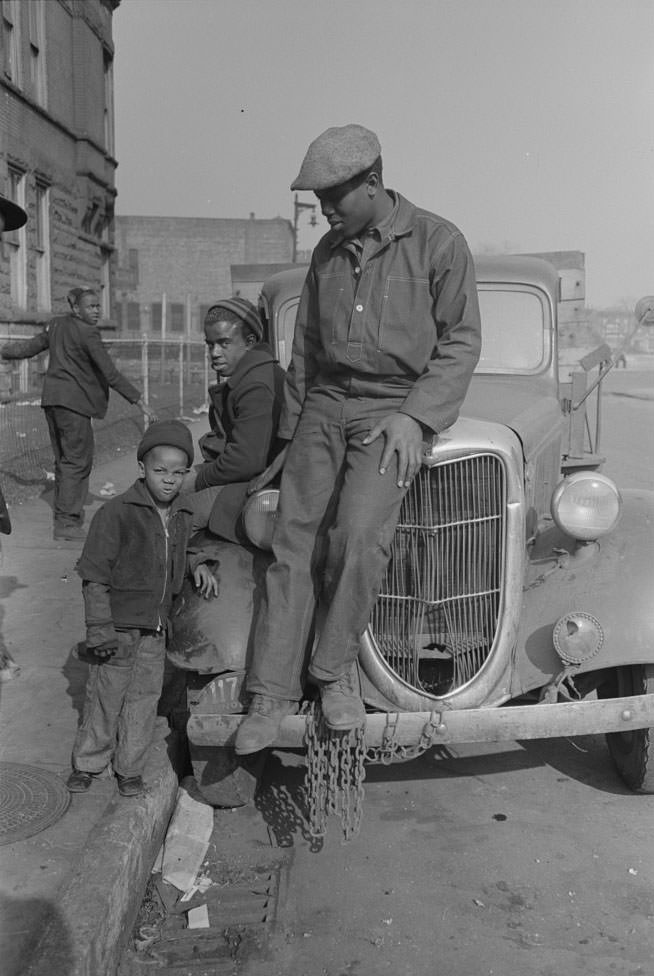

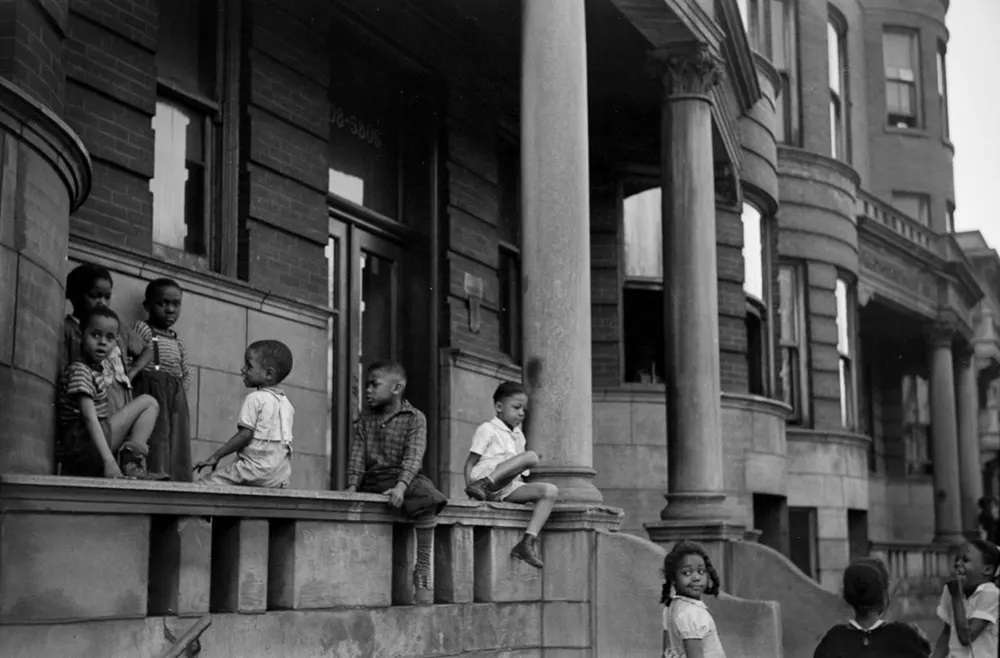

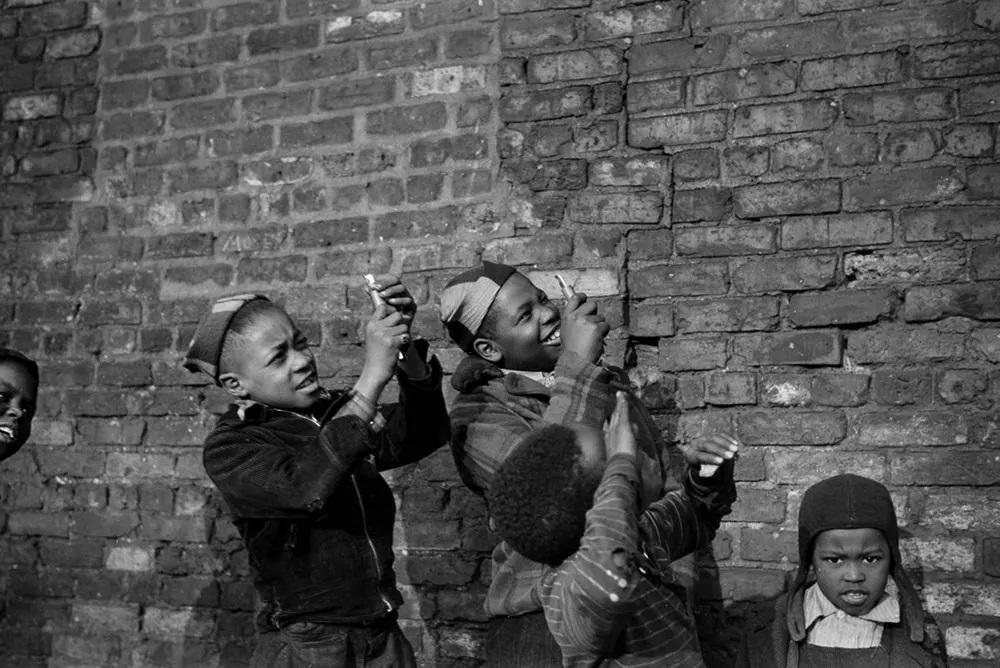

Many African-Americans left the South for Chicago during the Great Migrations of 1910 to 1960, creating an urban population. Before the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans of all classes lived on the South Side of Chicago as well as on the West Side. They started living in segregated communities regardless of income and strived to create neighborhoods where they could survive, sustain themselves, and determine their future. They established churches, community organizations, businesses, and music groups.

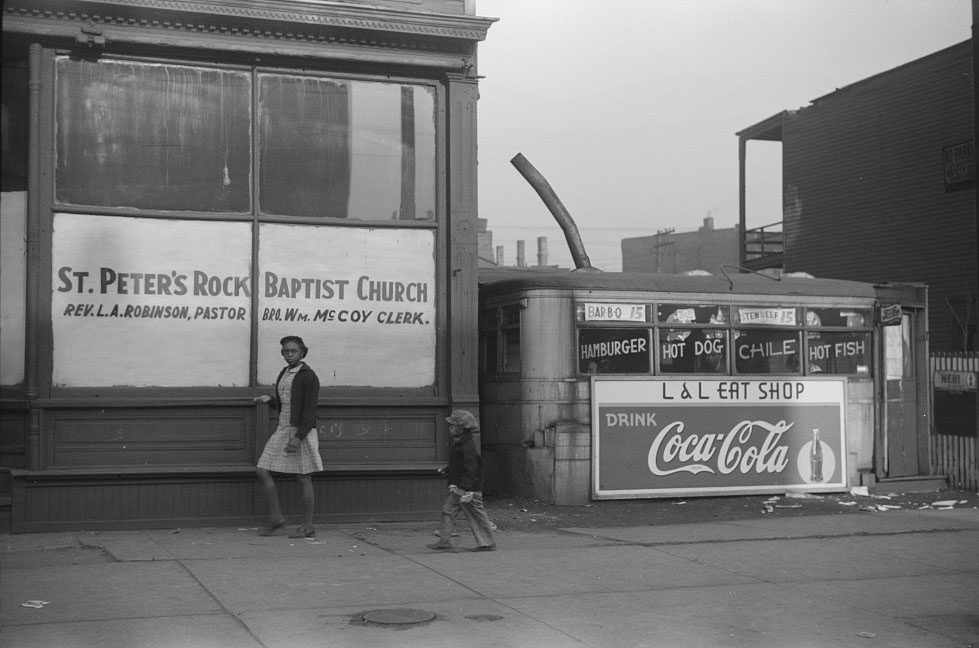

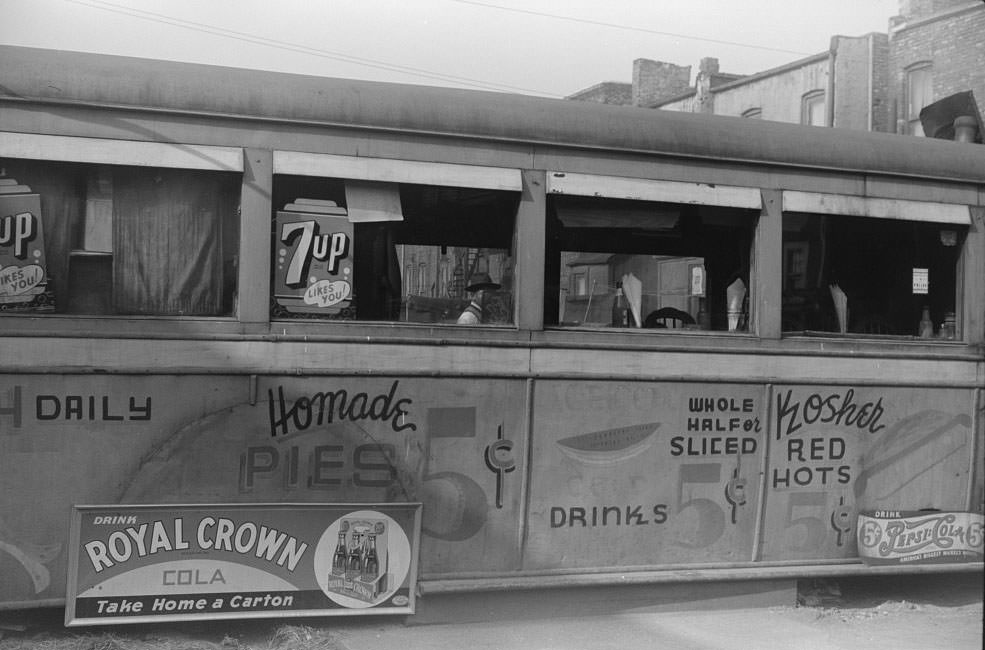

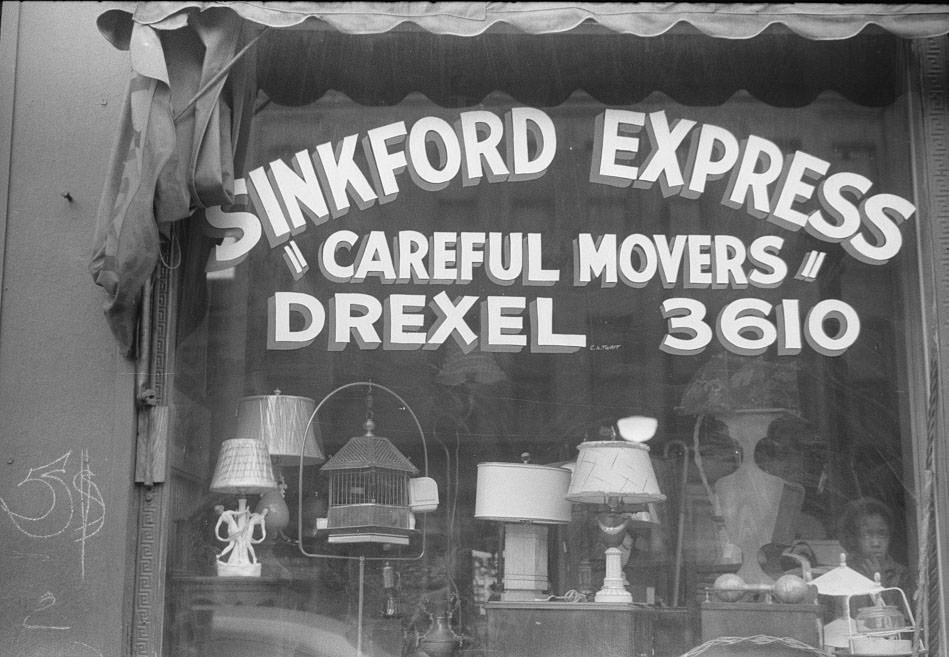

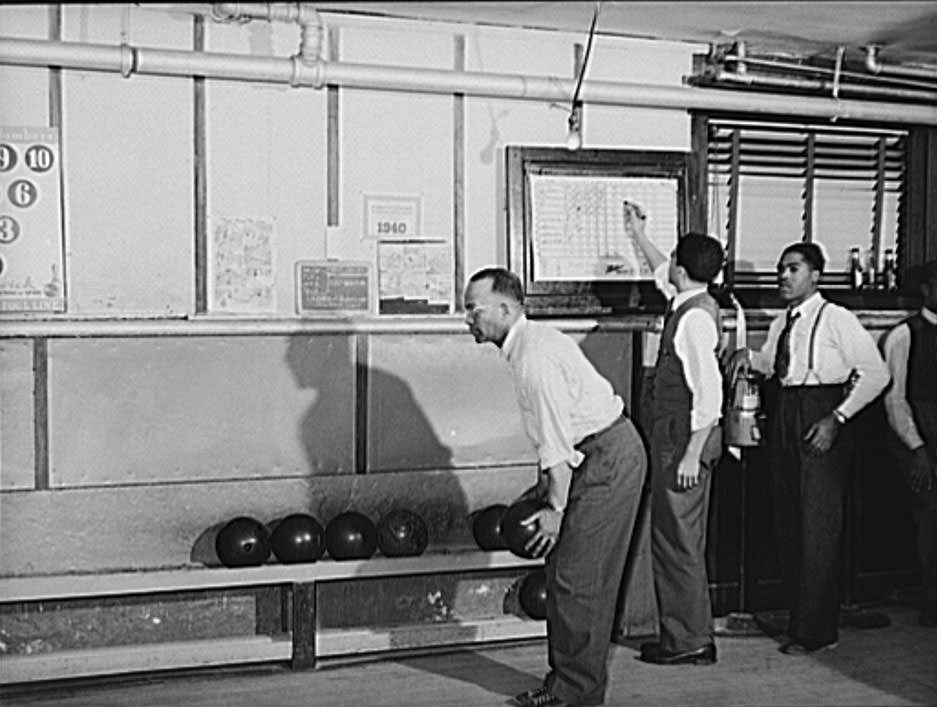

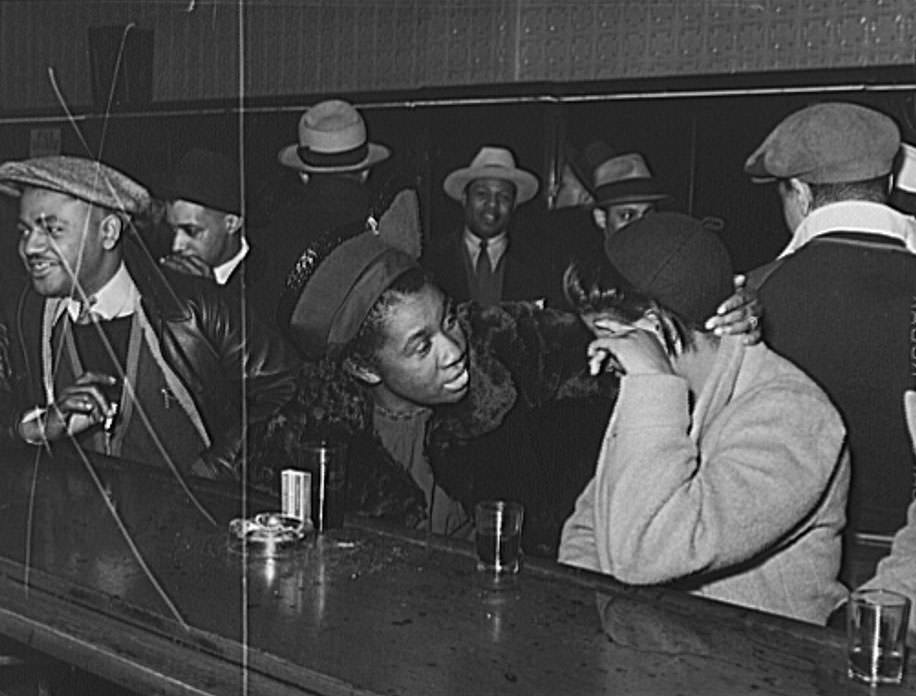

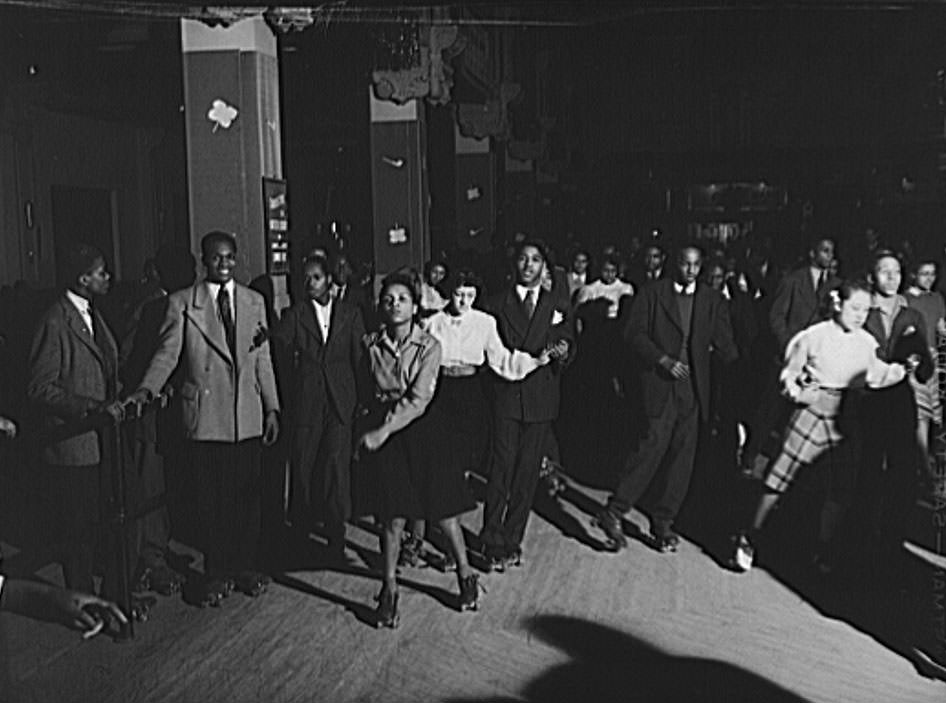

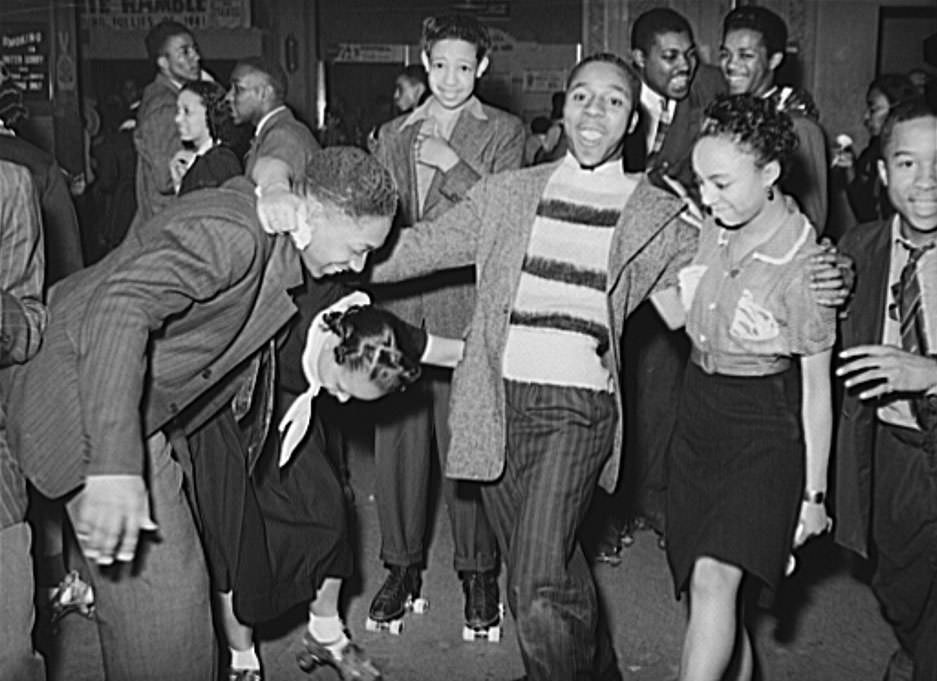

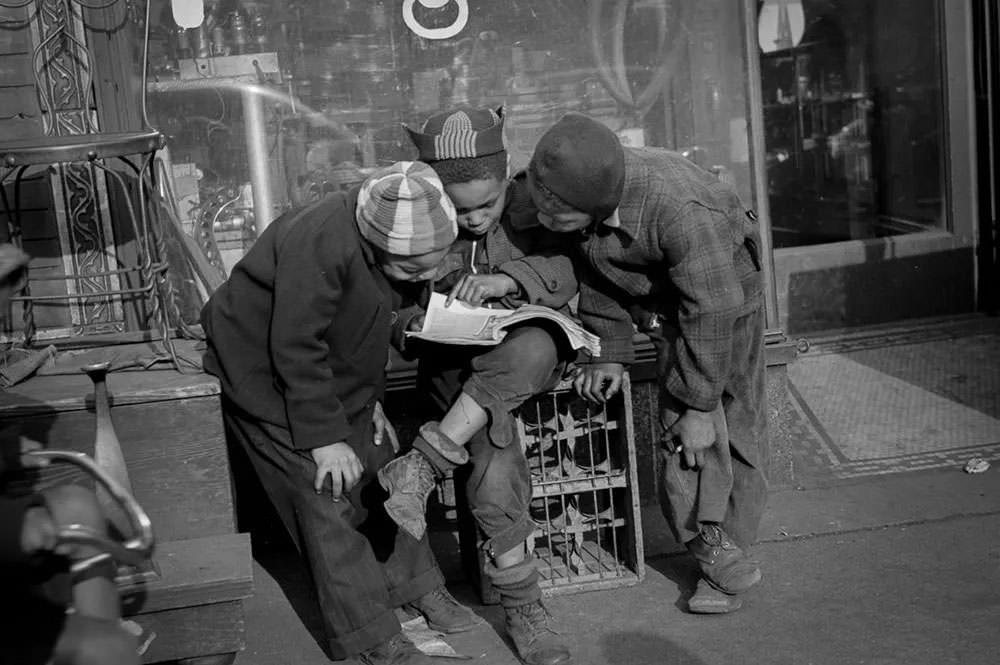

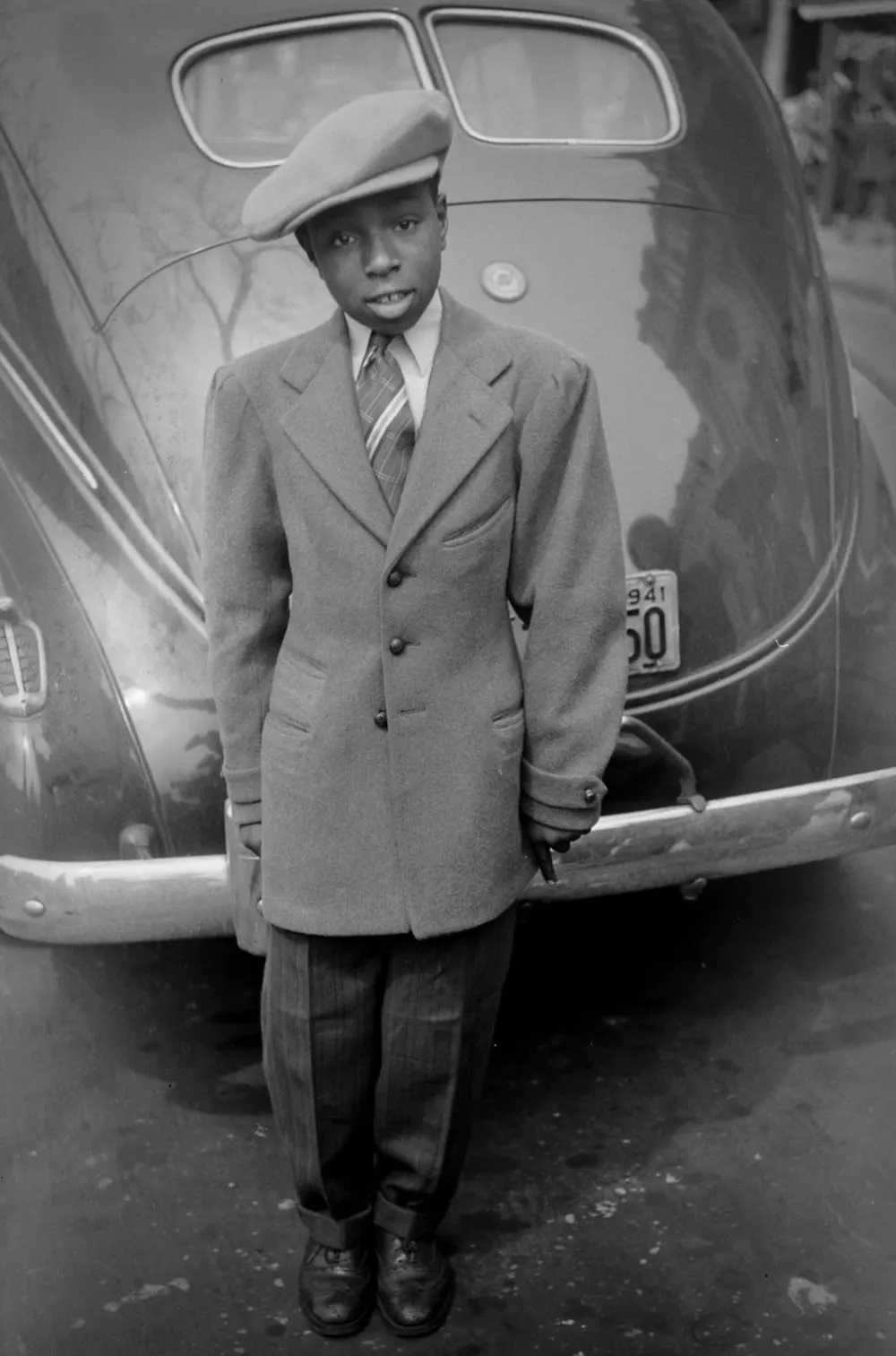

The South Side of Chicago became the center of African-American business and culture from the 1920s to the 1950s. At its peak, the narrow, seven-mile area was home to more than 300,000 people, but the neighborhood was surprisingly small. Chicago’s black population lived between the 22nd and 63rd streets between State Street and Cottage Grove. However, the pulsating energy of Bronzeville was centered around the busy intersections of 35th and State Street and 47th Street and South Parkway Boulevard (later renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive). People came to those intersections to eat, dance, shop, conduct business, and see the bustling black metropolis. There was a diverse mix of people in the black belt: young and old, poor and prosperous, professionals and laborers. There were many nightclubs and dance halls in Bronzeville. During the migration of Southern musicians, jazz, blues, and gospel music developed, attracting a broad audience.

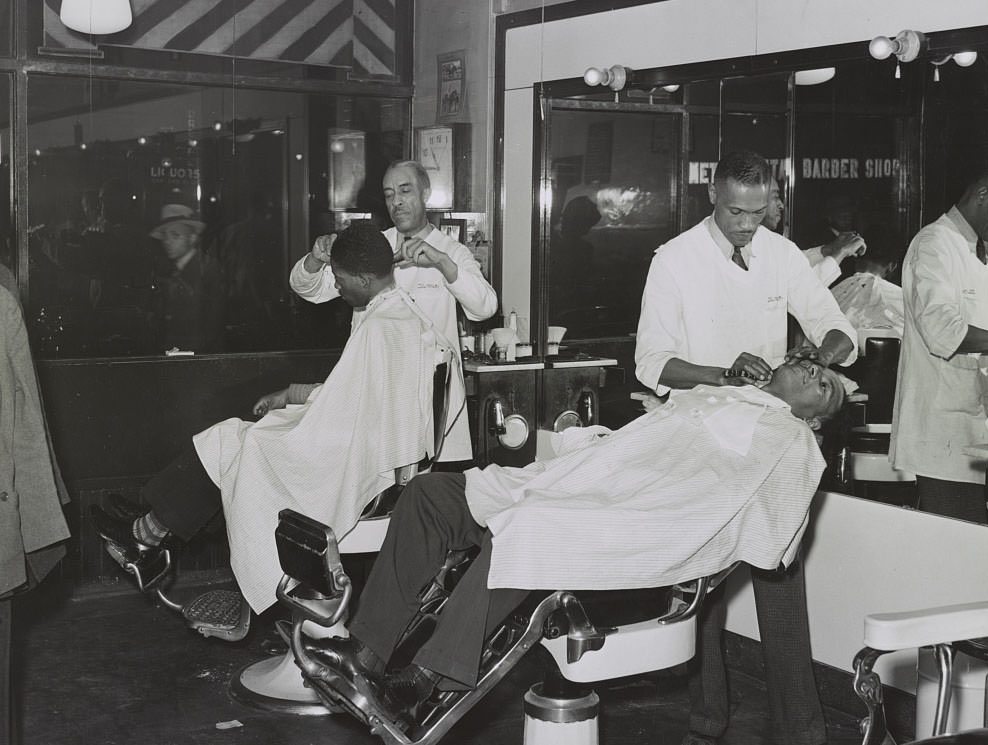

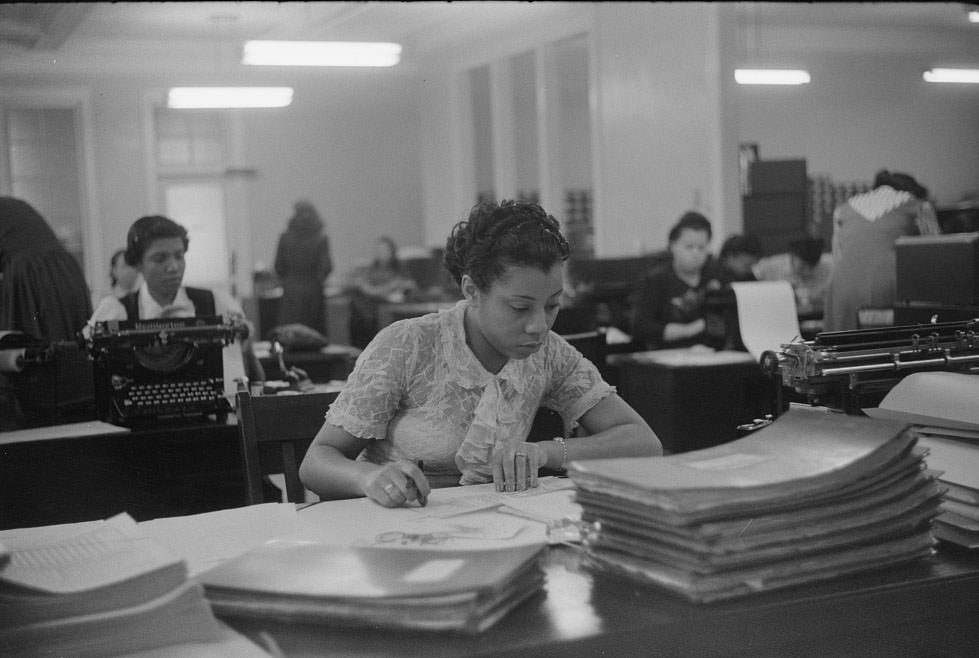

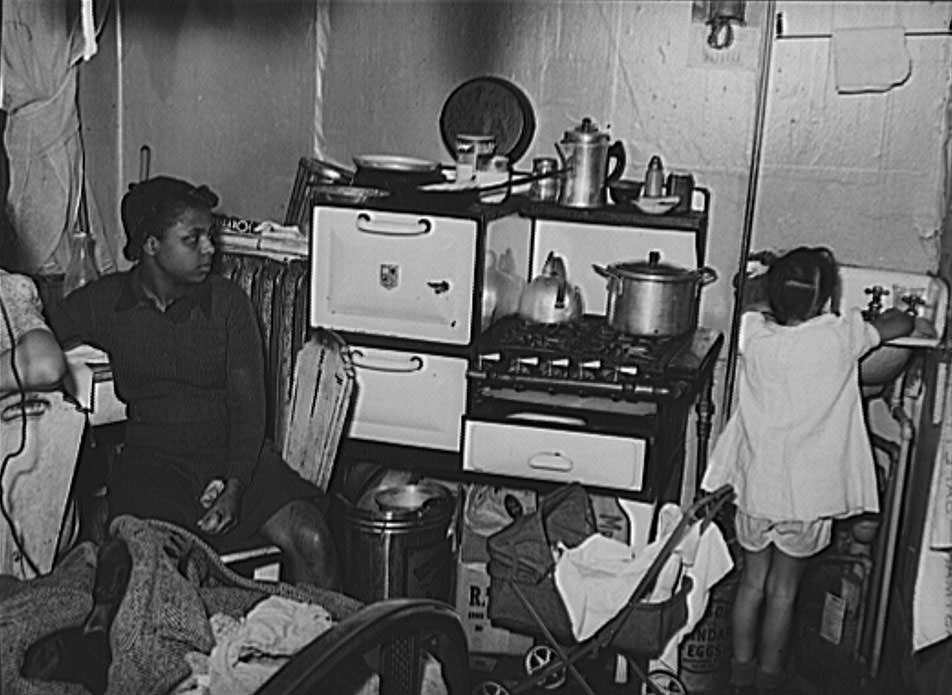

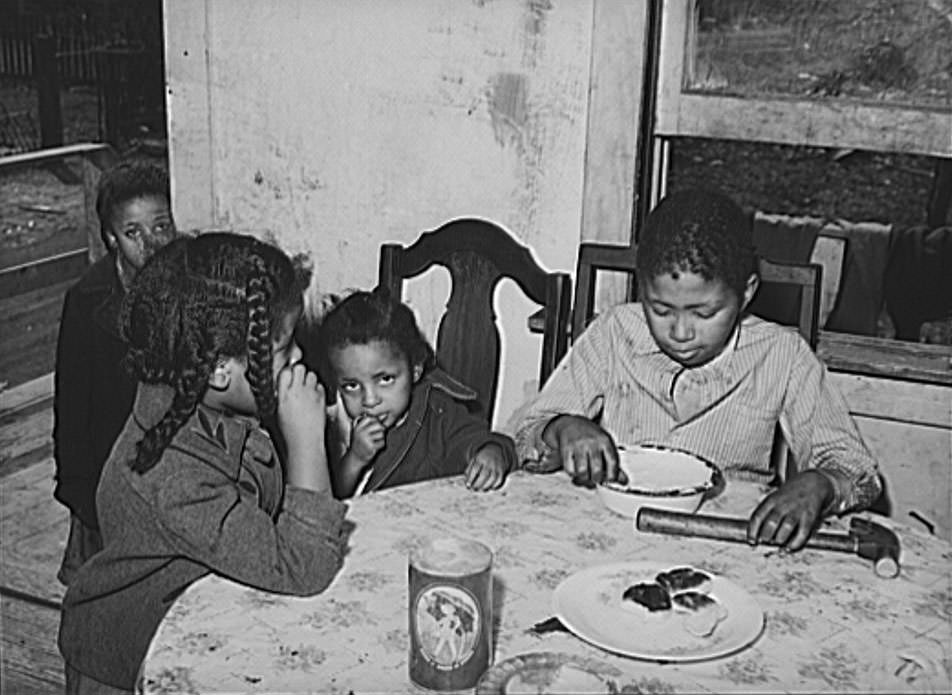

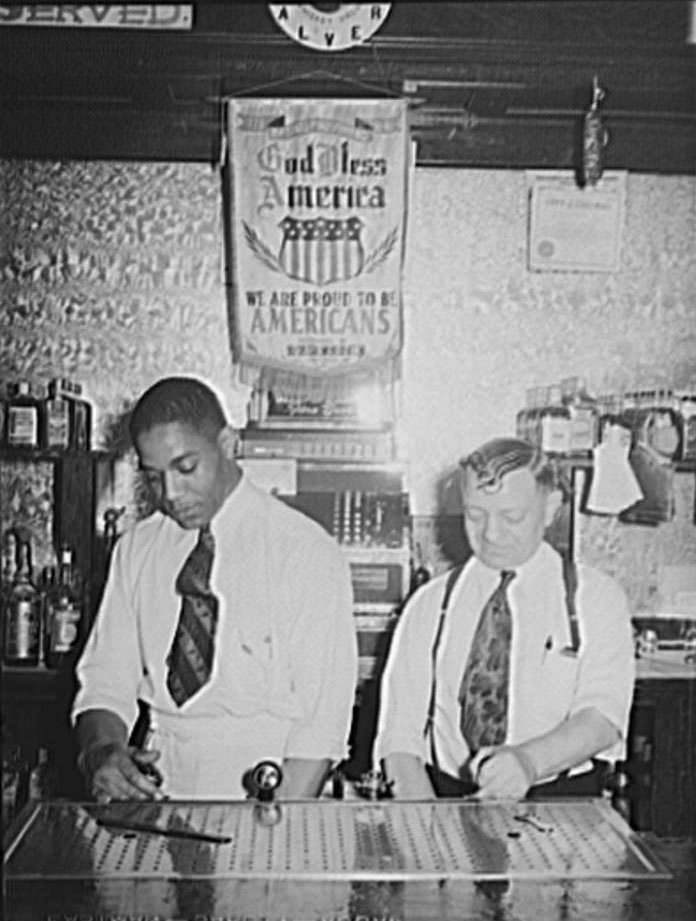

Chicago’s black population developed a class structure consisting of many manual laborers and domestic workers, alongside a small, but growing, class of middle- and upper-class business and professional elites. The city of Chicago expanded its professional class in 1929 when black Chicagoans gained access to city jobs. For African Americans in Chicago, fighting job discrimination was a constant struggle, as various employers restricted the advancement opportunities of black workers, which prevented them from earning higher wages. Beginning in the mid-20th century, blacks began to move up the ranks of the workforce.

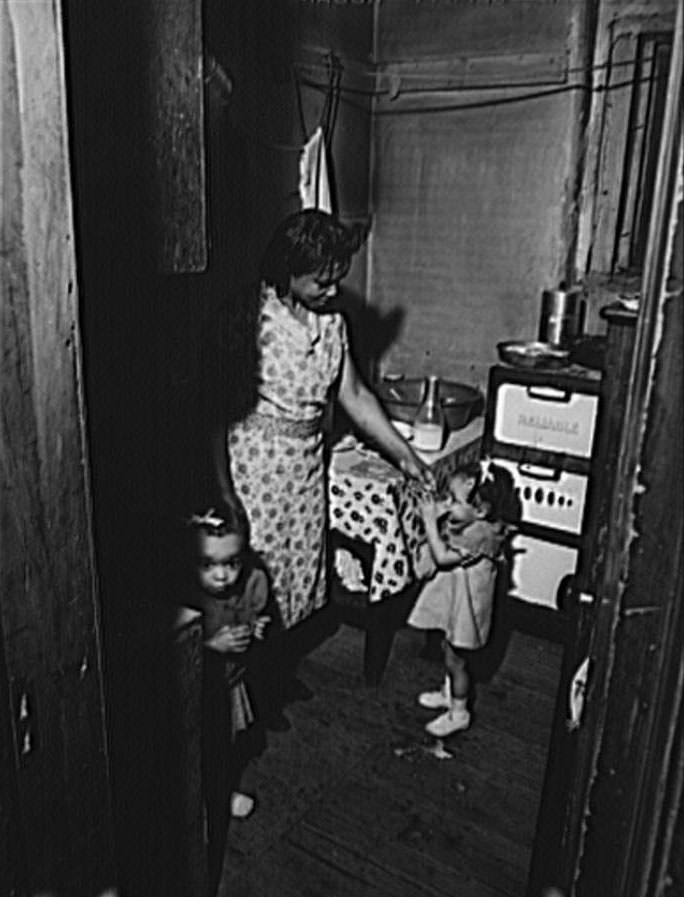

In 1941, the Farm Security Administration sent photographers Edwin Rosskam and Russell Lee to Chicago to document the everyday life of African-Americans. Their photographs show us Chicago Defender staff, roller-skaters, barbers, shoppers on Maxwell Street, nights out at The Regal, and worshippers at The Storefront Church on Easter.