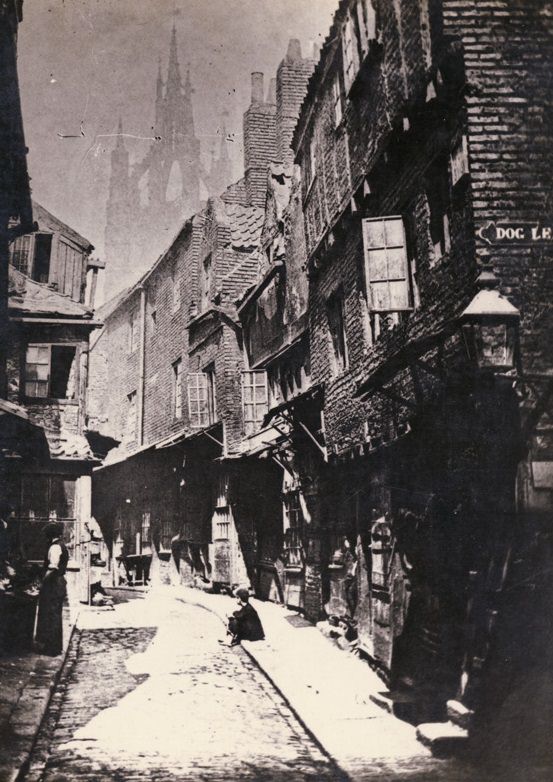

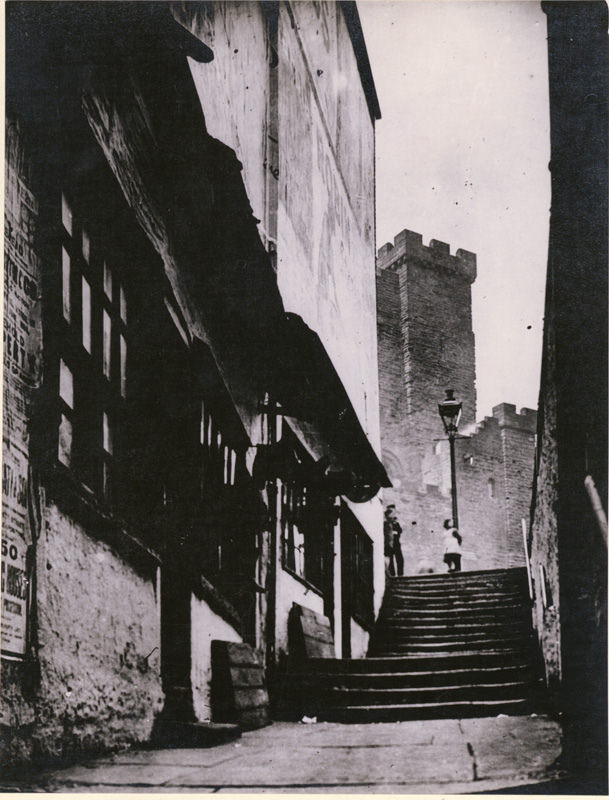

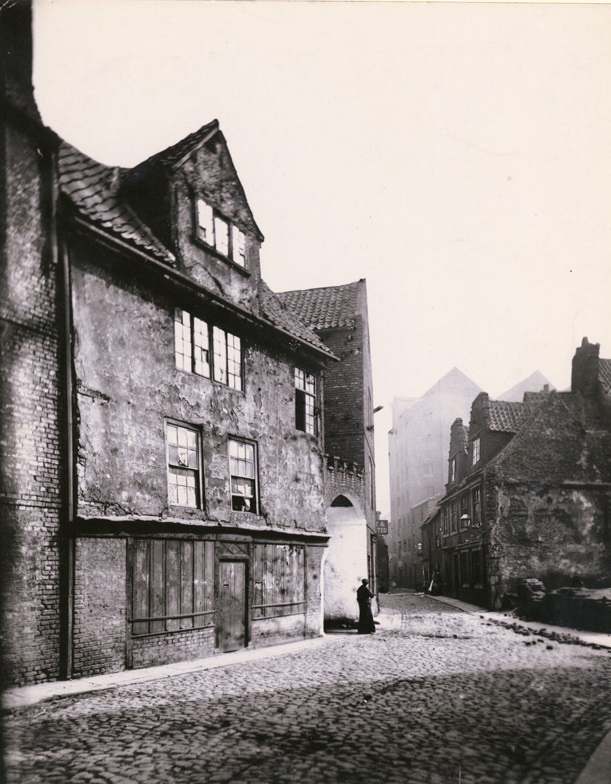

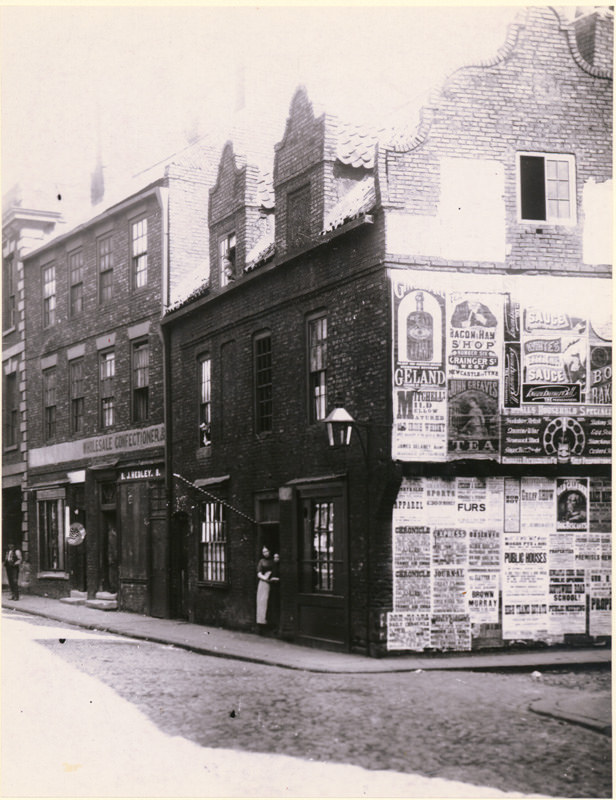

In the late 19th century, the city of Newcastle Upon Tyne was a thriving industrial hub in the north of England. As the 1880s dawned, this bustling city was undergoing significant transformations, both in terms of its physical landscape and the lives of its inhabitants.

The city’s economy was heavily reliant on heavy industries, such as shipbuilding, coal mining, and engineering. The River Tyne, which flows through the heart of Newcastle, was a crucial waterway for the movement of goods and materials. Shipyards along the river’s banks were a hive of activity, with workers constructing and repairing vessels that would carry cargo and passengers around the world.

Coal mining was another major industry in the region, and the city’s proximity to the rich coal seams of Northumberland and Durham made it an important center for this vital resource. Miners would descend deep underground to extract the coal, which was then transported to the city’s factories and power plants, fueling the engines of industry.

Read more

Beyond the shipyards and coal mines, Newcastle was also home to a thriving engineering sector. Factories and workshops dotted the cityscape, producing a wide range of machinery and equipment that were in high demand both locally and globally. The city’s engineers were renowned for their skill and innovation, constantly pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

As the 1880s progressed, the city’s population continued to grow, with people flocking to Newcastle in search of work and a better life. The influx of new residents led to the development of new neighborhoods and the expansion of existing ones. Rows of terraced houses sprang up, providing affordable accommodation for the city’s working-class families.

The city’s infrastructure also underwent significant improvements during this period. The construction of the Tyne Bridge in 1867 had made it easier for people and goods to move across the river, and in the 1880s, the city’s tram network was expanded, making it easier for residents to navigate the city.

One of the most notable developments in Newcastle during the 1880s was the construction of the iconic Central Station. Opened in 1850, the station had become increasingly crowded and outdated by the end of the 19th century. In 1878, a decision was made to demolish the old station and build a new, larger facility that could accommodate the growing number of passengers and trains.

The new Central Station, designed by the renowned architect John Dobson, was a magnificent example of Victorian architecture. Its grand, neo-Gothic façade and soaring arched roof became an iconic landmark in the city, symbolizing Newcastle’s status as an important transportation hub.

Alongside the city’s industrial and infrastructural developments, the 1880s also saw a flourishing of cultural and social life in Newcastle. The city’s theaters and music halls were bustling with activity, hosting a wide range of performances, from classical concerts to variety shows.

One of the most popular entertainment venues was the Theatre Royal, which had first opened its doors in 1837. By the 1880s, it had become a hub of cultural activity, attracting audiences from across the region to see the latest plays, operas, and musical performances.

The city’s literary scene was also thriving, with several prominent authors and poets calling Newcastle home. One such figure was the Geordie poet, Joseph Skipsey, whose work celebrated the lives and struggles of the city’s working-class residents.

Beyond the arts, the 1880s also saw the growth of various social and political movements in Newcastle. The city was a stronghold of the trade union movement, with workers organizing to fight for better wages and working conditions. The city’s growing middle class also became increasingly involved in civic affairs, advocating for improvements to public health, education, and infrastructure.

One of the most significant political developments in Newcastle during the 1880s was the rise of the Liberal Party. The city had traditionally been a Conservative stronghold, but the Liberals were able to make significant inroads, winning several local and national elections. This shift in the political landscape was driven in part by the city’s growing middle class, who were drawn to the Liberals’ progressive agenda.