In the spring of 1942, the lives of Japanese Americans changed drastically. The attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan on December 7, 1941, created fear and suspicion across the United States. People were worried about national security, and this fear quickly turned into prejudice against Japanese Americans. The repercussions were immediate and severe. Prominent Japanese Americans were arrested, and many lost their jobs. They were subjected to verbal and physical attacks, and their achievements were disregarded.

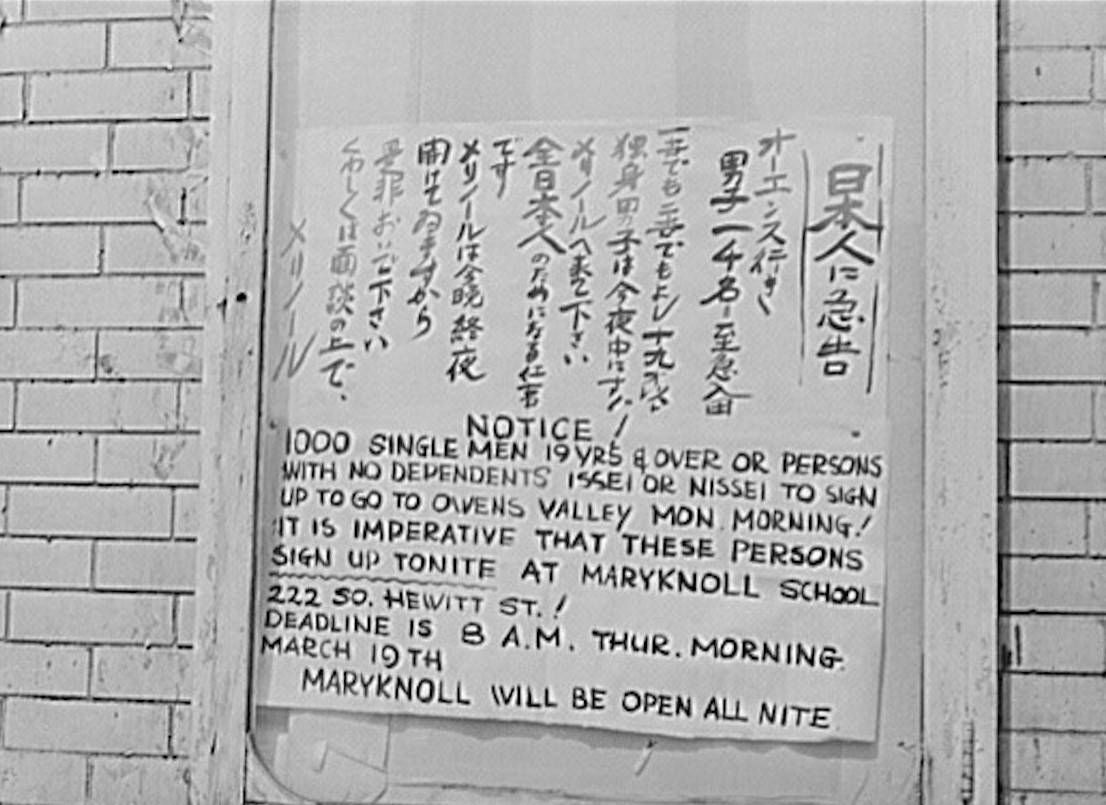

The situation worsened when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the evacuation and relocation of “any and all persons” from designated military areas. Soon after, California, along with much of Washington and Oregon, was declared a military area. Japanese Americans were viewed as potential threats, suspected of supporting Japan in the war. This suspicion was based on fear rather than any evidence.

General John L. DeWitt, the head of the Western Defense Command, played a key role in enforcing this order. He issued a military proclamation that imposed a curfew on all Japanese Americans living in the West Coast states. This curfew restricted their movements and increased the feeling of isolation and fear. The process of relocating tens of thousands of Japanese Americans to prison camps began shortly after.

Read more

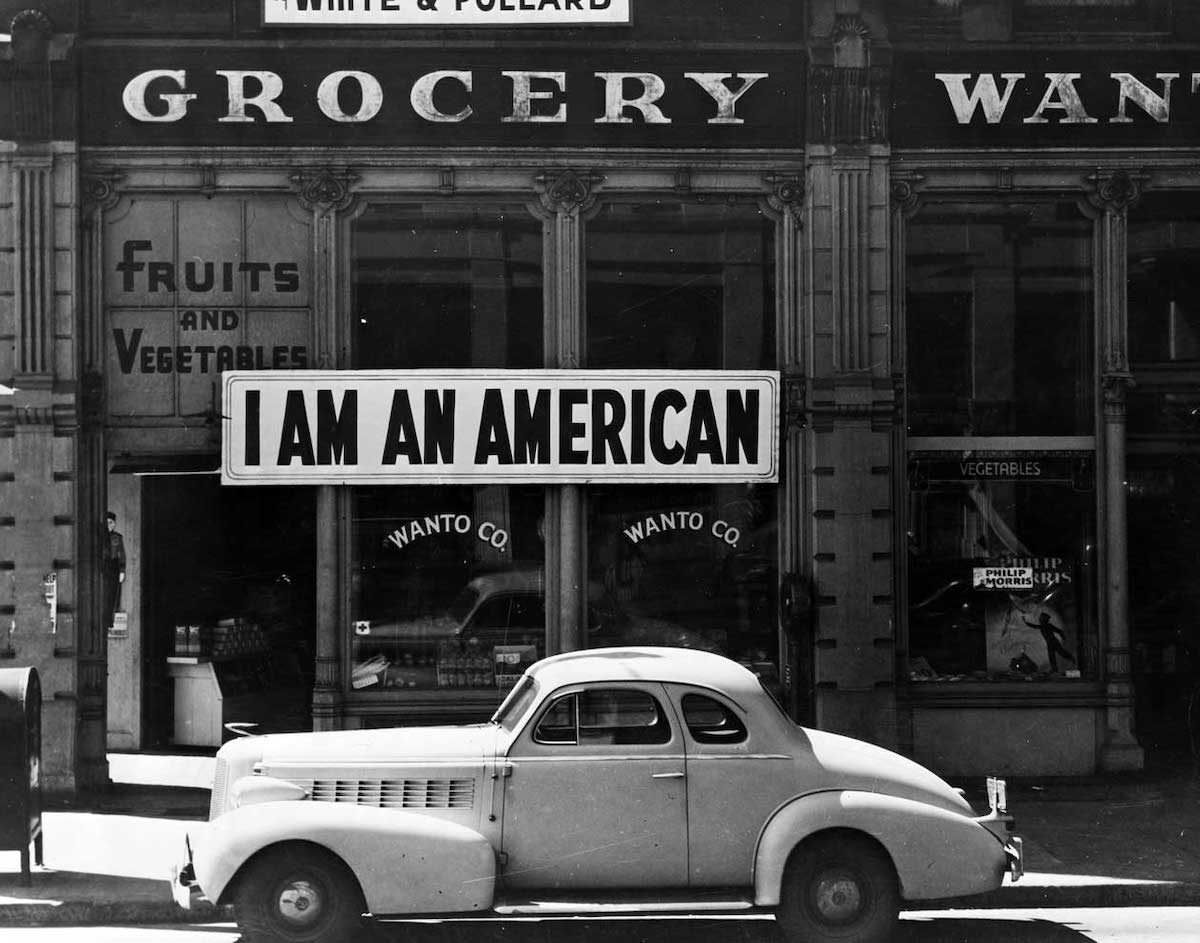

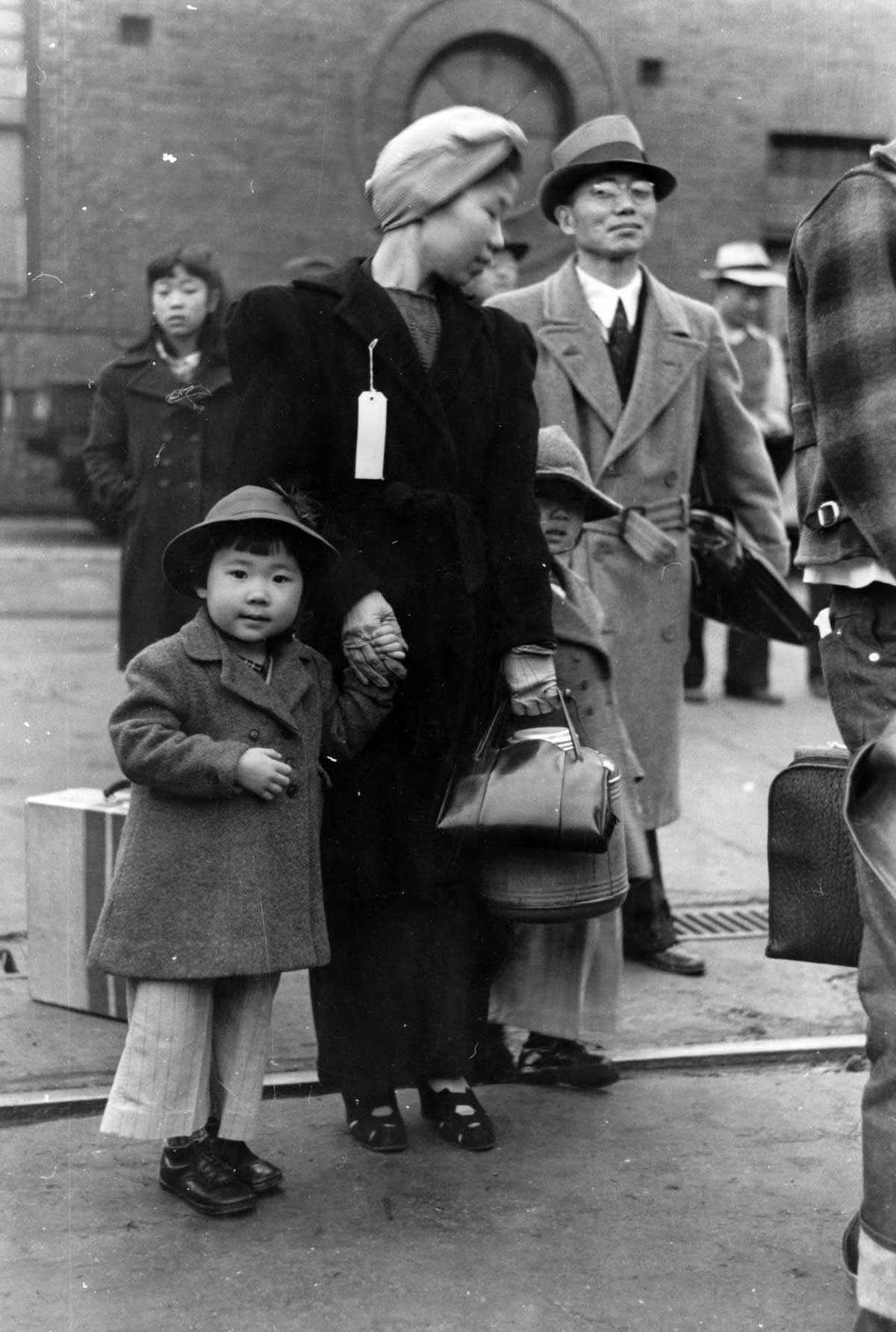

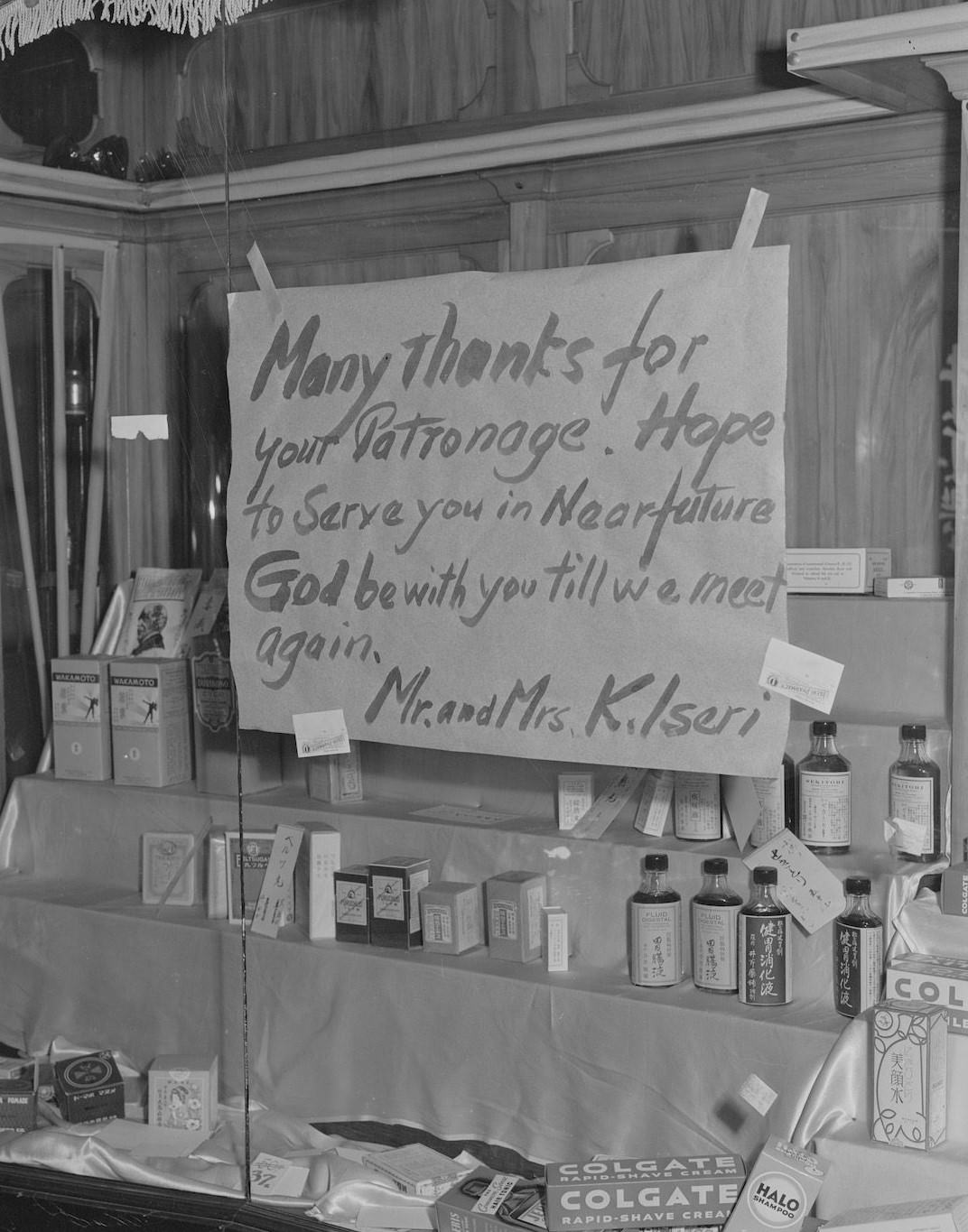

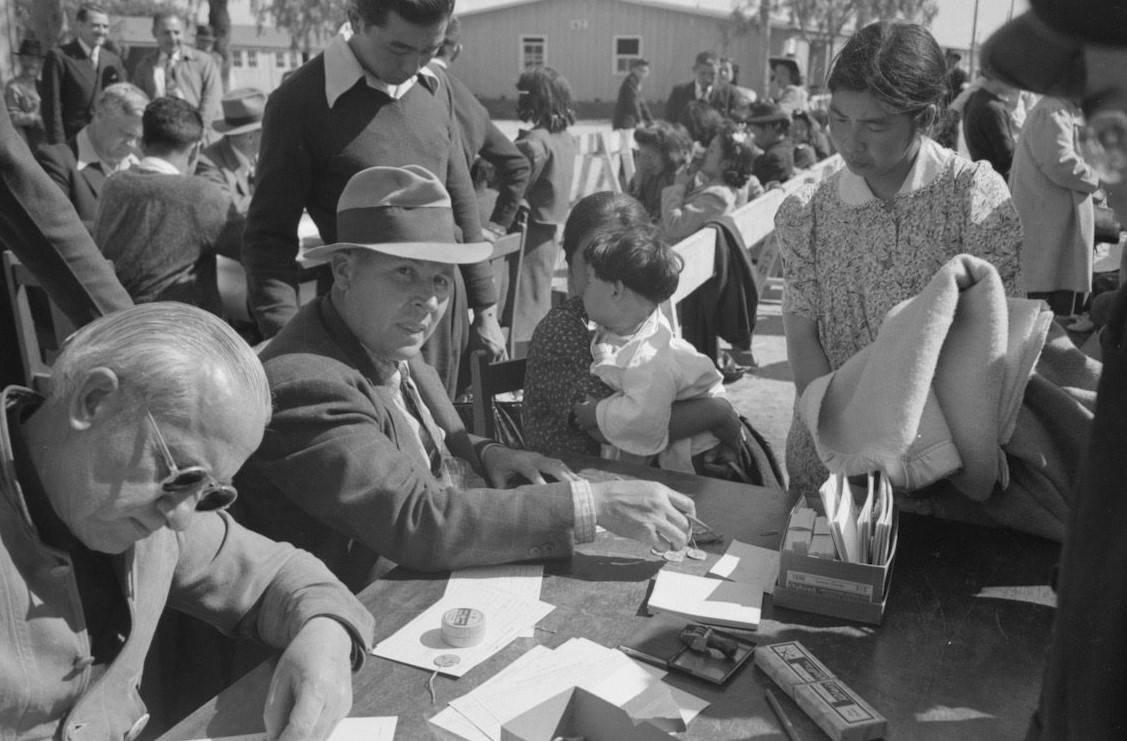

Japanese Americans were ordered to register with the government. They were given identification numbers and inoculations against communicable diseases. In a matter of days, they had to sell their homes, farms, businesses, and possessions. Many families were forced to abandon everything they had built. They were treated as enemies of the state, criminals in waiting, despite being loyal American citizens.

Evacuees were directed to gather at large locations, such as racetracks and fairgrounds. Around 120,000 Japanese Americans were housed in temporary accommodations made of tents and stables. These makeshift living spaces offered little comfort. Families waited there for their assignments to war relocation camps, which were located in remote and inhospitable areas.

When the camps were finally established, they were surrounded by barbed wire. Armed guards stood watch from tall towers, keeping a close eye on the prisoners. Families were crammed into single rooms, often with little privacy. The living conditions were harsh, and the sense of freedom was completely stripped away.

Despite the difficult circumstances, Japanese Americans tried to maintain a sense of normalcy. They set up schools and community centers within the camps. People began producing newspapers to keep their spirits alive and share news. They also organized social groups to support one another during this challenging time.

To obtain necessary goods, families could take supervised trips to nearby towns, such as Nyssa, Oregon. These trips allowed them to buy food and supplies, but they were still confined to the camps. If they needed clothing or other items, they often ordered from mail-order catalogs, especially the Sears Roebuck catalog. This was one of the few ways they could access basic necessities.

Communication with the outside world was limited but available. They could send letters and use communal pay phones to reach family and friends. However, the reality remained that they were not free. The camps were a constant reminder of their imprisonment and the loss of their rights as American citizens.

As the days turned into weeks and then months, life continued in the camps. Families adapted to their new surroundings, creating gardens, organizing classes, and forming sports teams. Children played together, trying to find joy in their confined environment. Adults worked on projects to improve their living conditions, striving to create a sense of community.

The experience was traumatic for many. People faced the loss of their homes, their businesses, and their freedom. The psychological impact of being labeled as enemies in their own country was immense. Many felt betrayed by a nation they had always considered home. Despite the hardships, the resilience of the Japanese American community shone through.