In the shadowed corridors of World War II‘s global conflict, an unprecedented scientific endeavor was secretly underway. Codenamed the Manhattan Project, this monumental effort would culminate in the Trinity Test, forever changing the trajectory of warfare, international relations, and our understanding of the universe’s most fundamental forces.

Genesis of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project had its roots in a simple but alarming letter. In 1939, Albert Einstein and fellow physicist Leo Szilard penned a note to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning of the potential for Nazi Germany to harness the immense power of nuclear fission. This sparked a chain of events leading to the most ambitious scientific undertaking of the 20th century.

Assembling the Brightest Minds

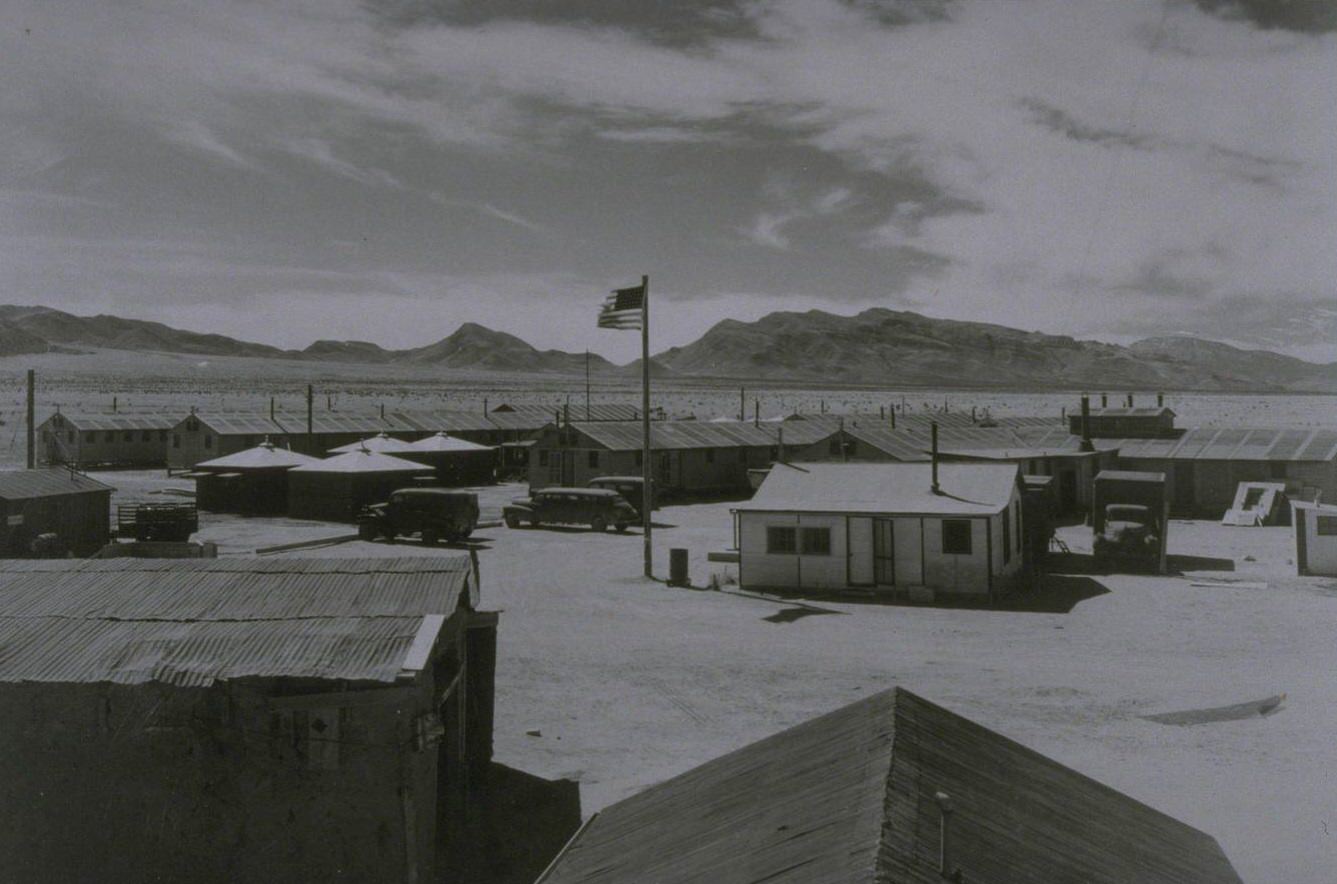

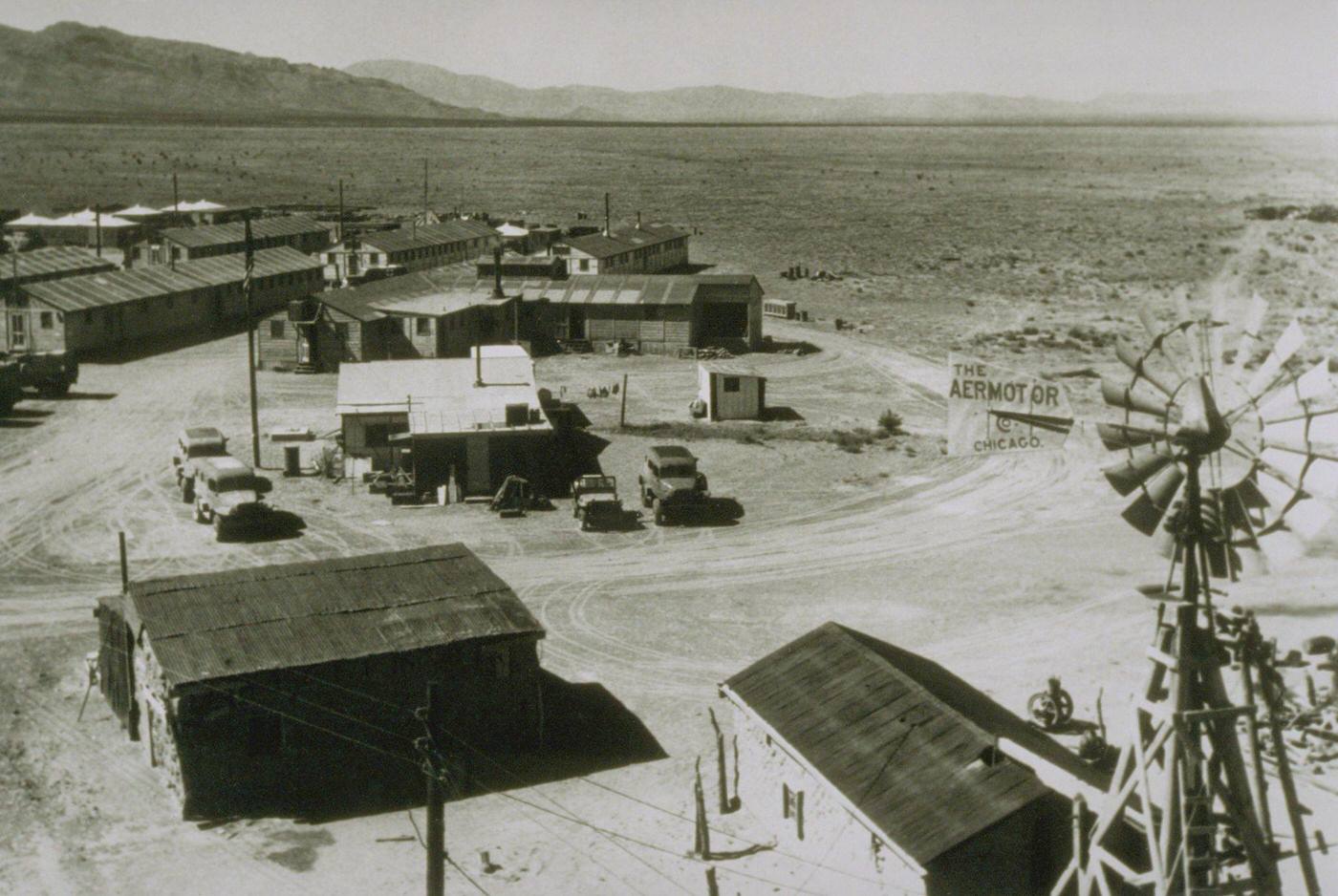

The U.S. soon began gathering its top scientists and engineers in secret locations, most notably Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Under the leadership of J. Robert Oppenheimer and supported by figures like Richard Feynman and Enrico Fermi, they worked on understanding and harnessing nuclear reactions.

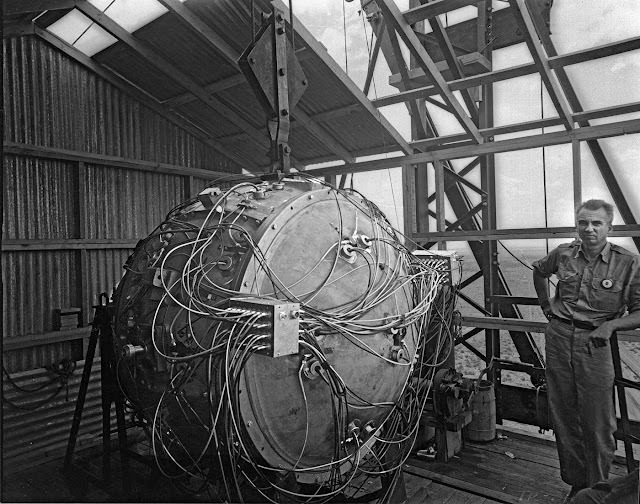

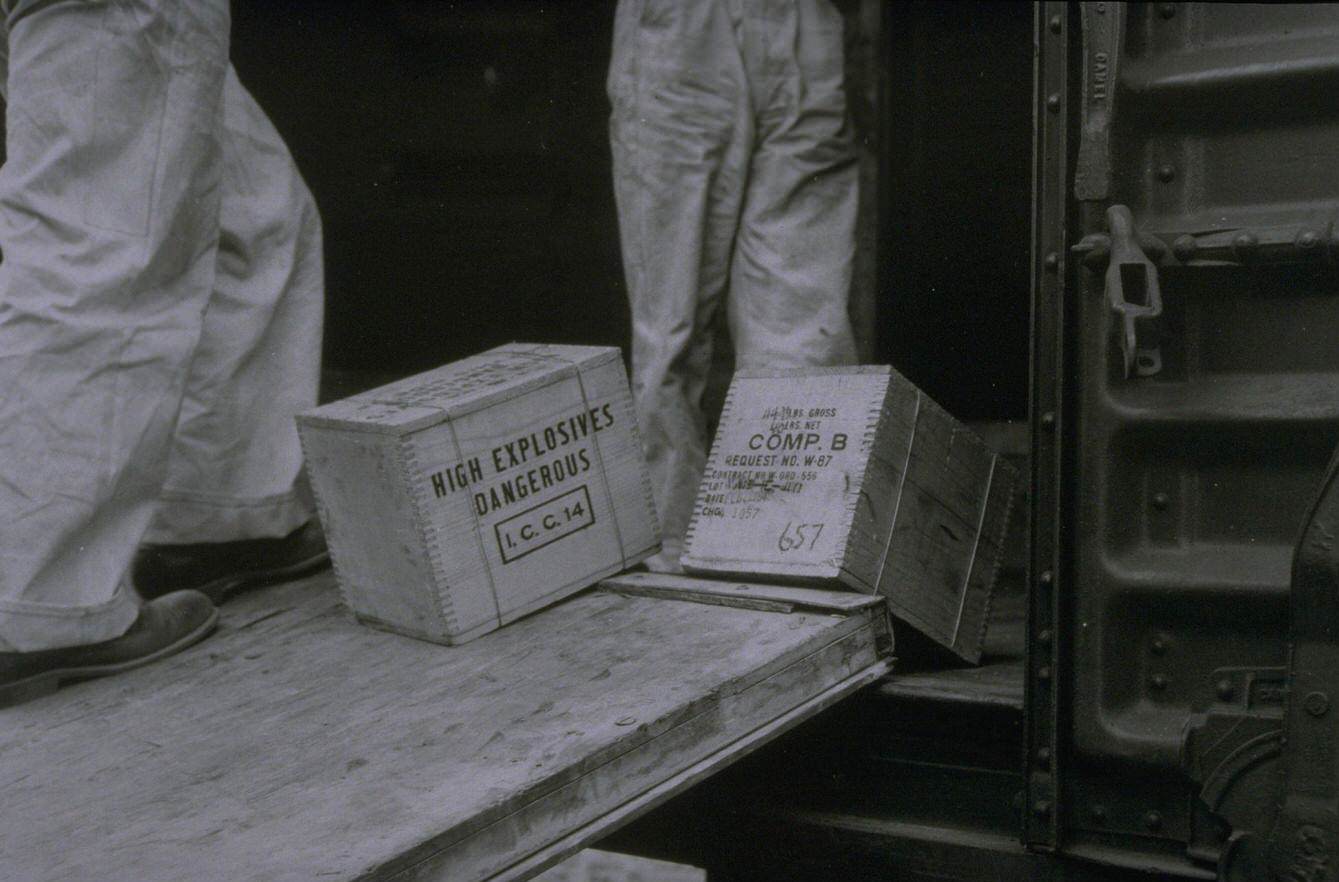

The challenges were immense. From isolating plutonium to inventing new methods to trigger nuclear reactions, the project pushed the boundaries of science. The researchers faced ethical and technical dilemmas as they grappled with creating a weapon of unprecedented destructiveness.

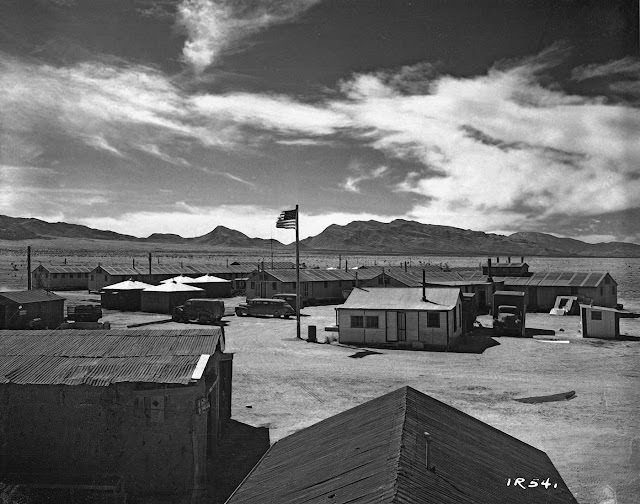

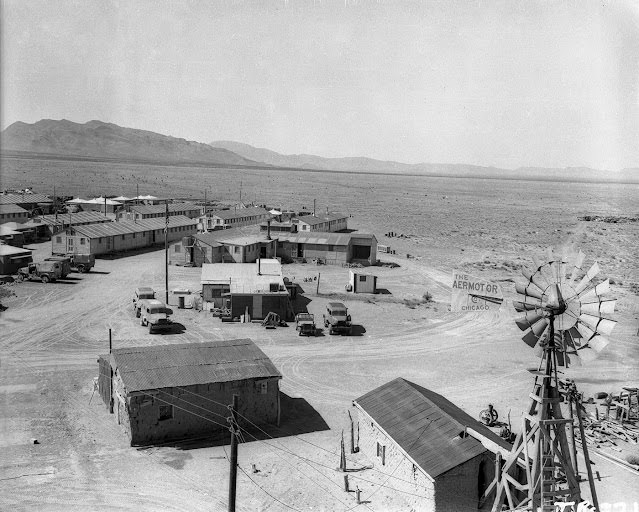

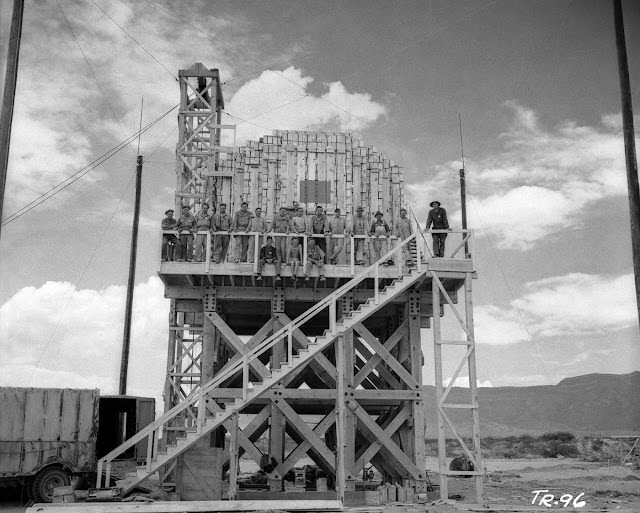

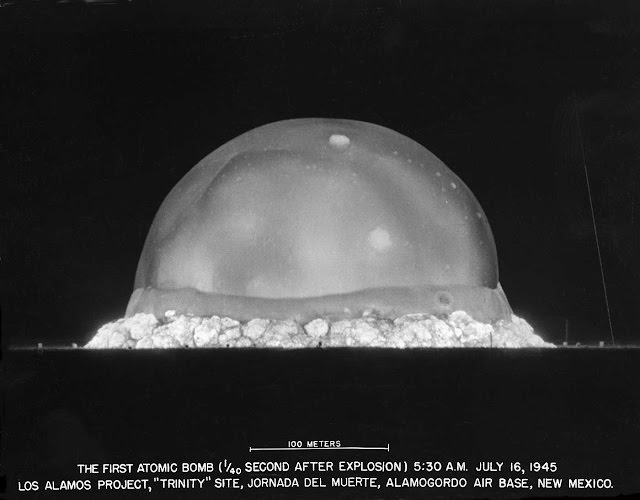

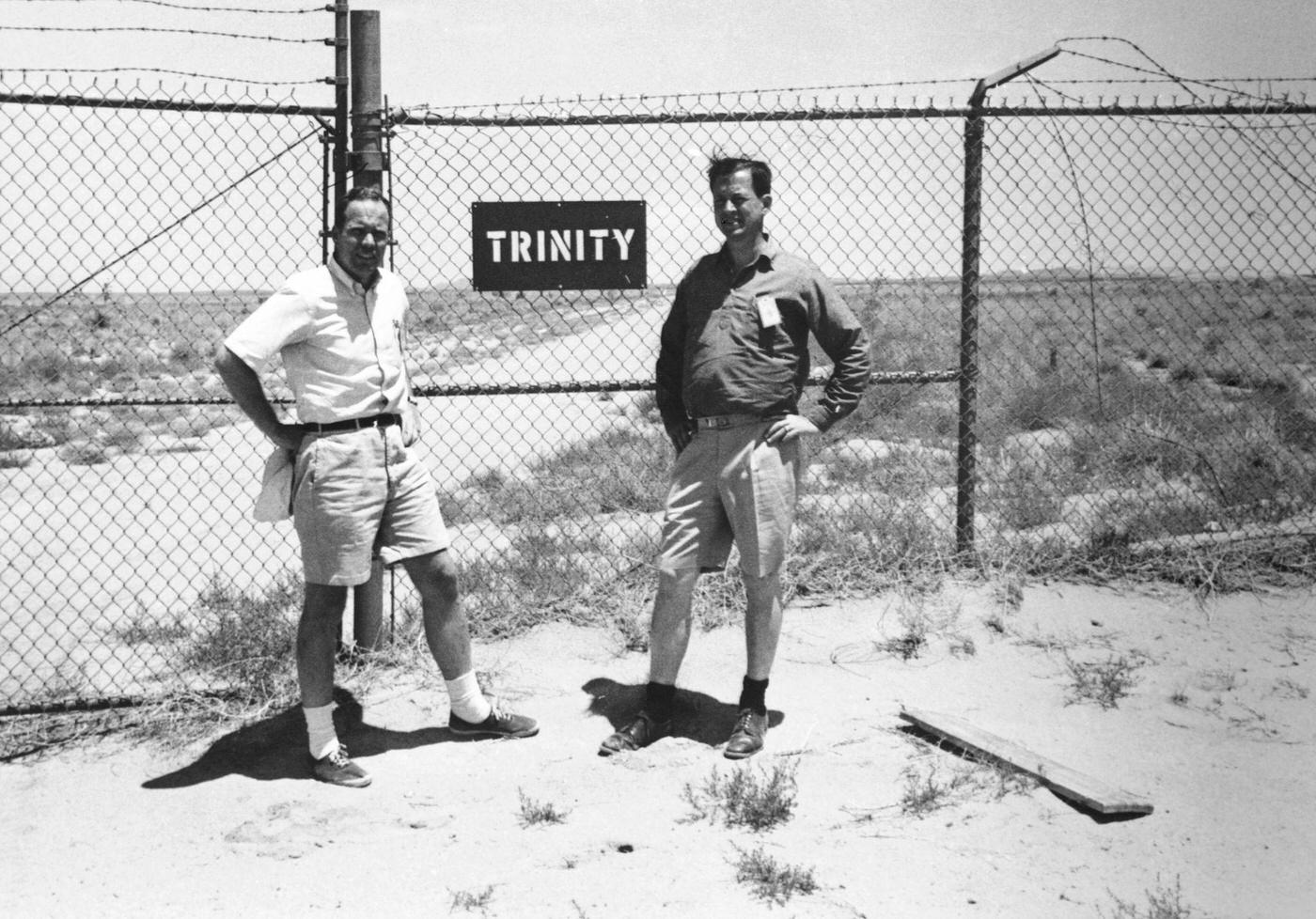

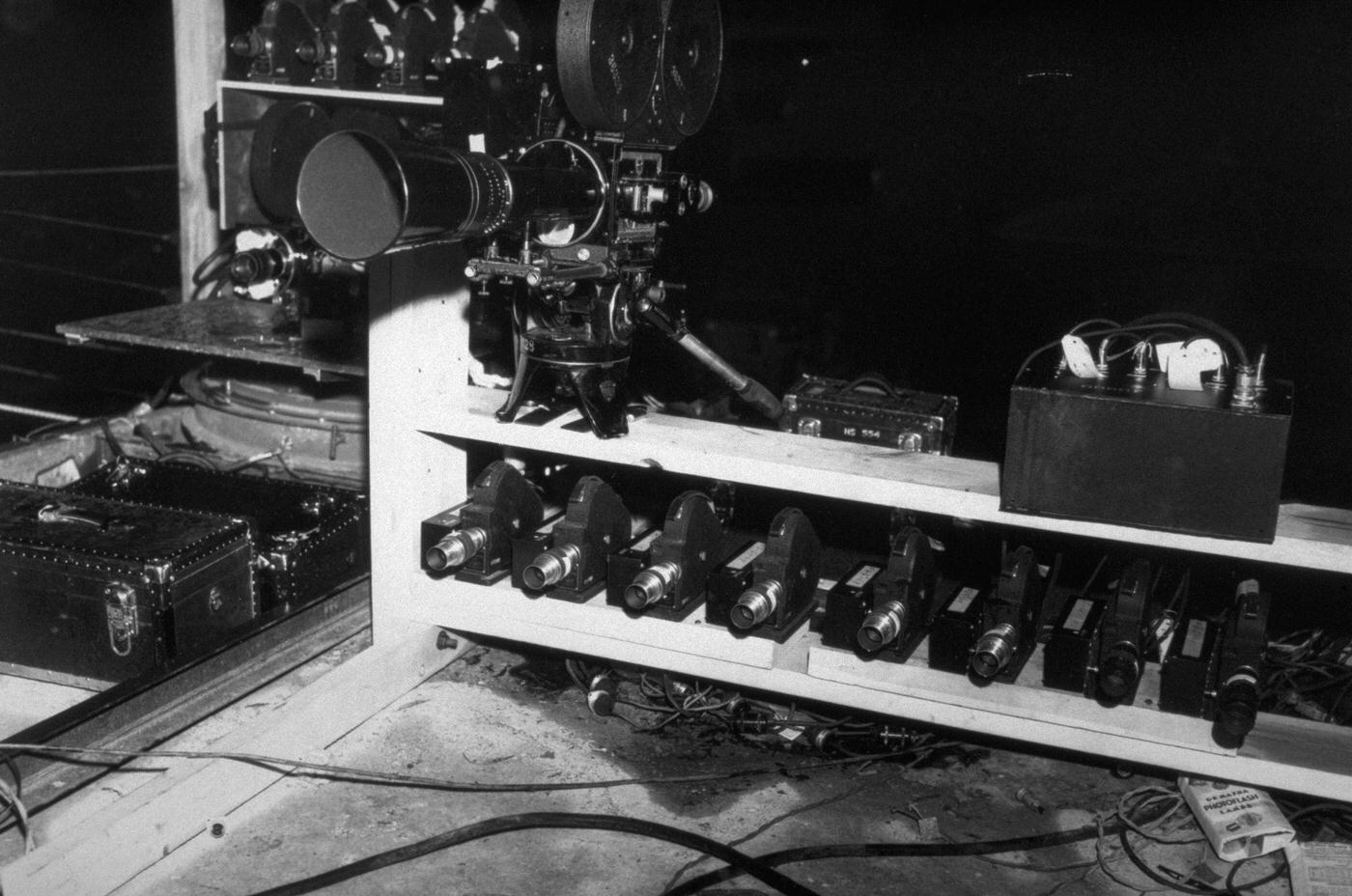

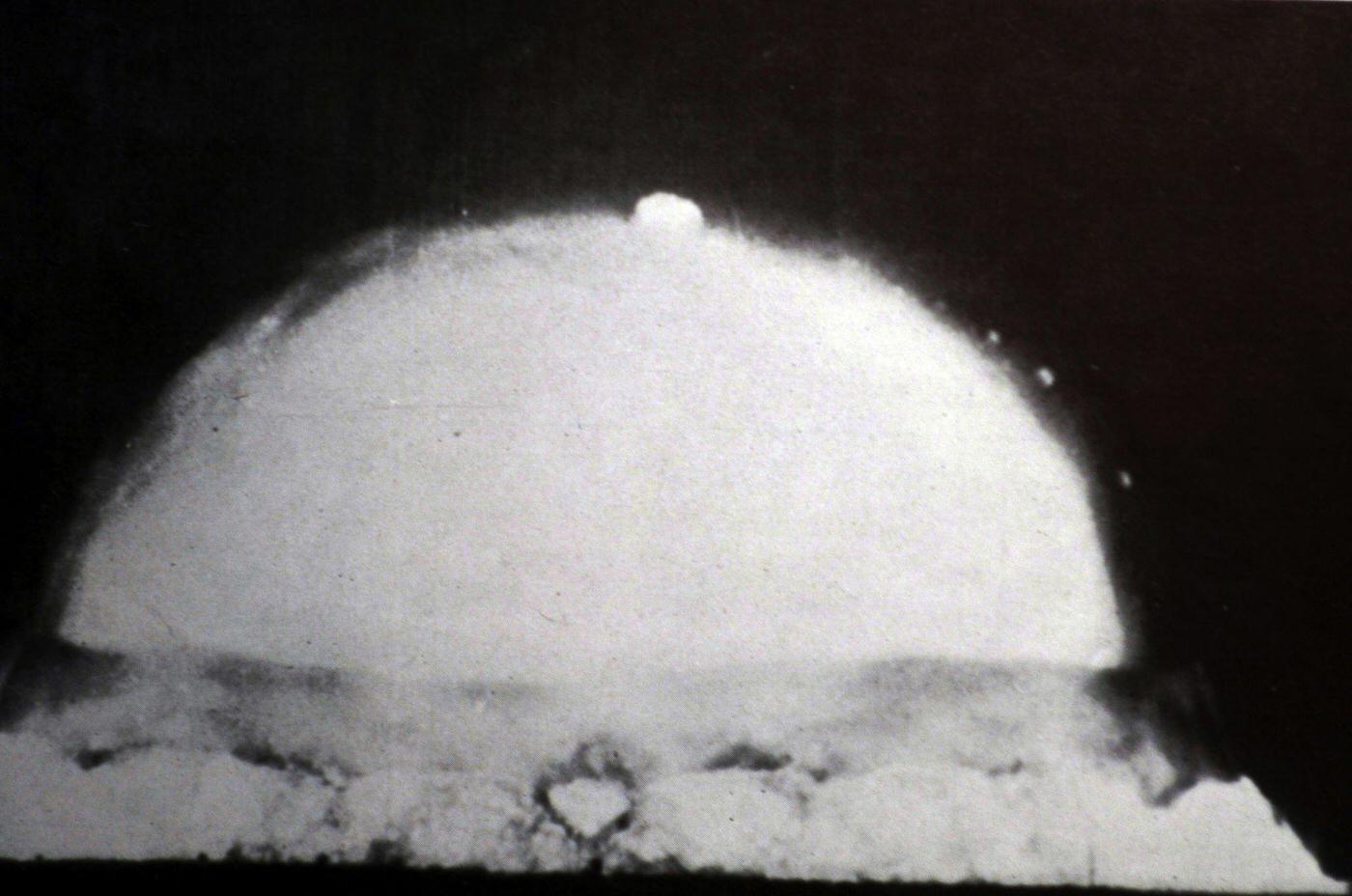

The Trinity Test: The World’s First Nuclear Detonation

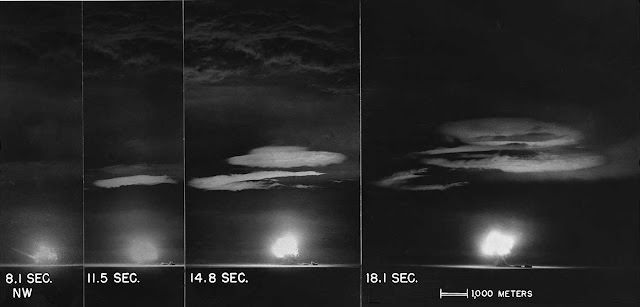

On July 16, 1945, in a desolate desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico, the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated. Codenamed “Trinity,” the test was a searing validation of the Manhattan Project’s success. Observers several miles away felt the heat on their faces, and the bright flash, even with goggles on, momentarily blinded them. The mushroom cloud, now an infamous symbol, ascended into the skies.

Beyond its military implications, the Manhattan Project paved the way for numerous scientific and technological advancements. Nuclear energy, medical applications of radioisotopes, and advancements in particle physics all have their roots in this era. Laboratories established during the project, like Los Alamos and Oak Ridge, continue to contribute to cutting-edge research today.

The atomic age seeped into every facet of American culture. From films and literature to art and music, the bomb and its implications became a recurrent theme. The counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, particularly, saw a strong anti-nuclear sentiment, symbolized by peace movements and protest songs.