When one imagines Ireland, lush verdant landscapes and ethereal coastlines often spring to mind. But for decades, our glimpse into the nation’s past was painted in shades of monochrome. That was, until two Frenchwomen, Marguerite Mespoulet and Madeleine Mignon-Alba, embarked on an unprecedented journey in 1913, capturing the heart and soul of Ireland in color for the first time.

The Adventurous Duo

Marguerite Mespoulet and Madeleine Mignon-Alba were not renowned photographers. They were, in fact, relatively novice in the realm of photography. But their determination and adventurous spirit outweighed their inexperience. They packed their bags, equipped themselves with cutting-edge technology – the Autochrome Lumière cameras, and set sail for Ireland as part of an ambitious worldwide endeavor known as “The Archives of the Planet.”

This revolutionary project, helmed by French banker and philanthropist Albert Kahn, aimed to create a “photographic inventory of the surface of the earth as it was occupied and organized by Man at the beginning of the 20th century.”

The Birth of Color Photography

Black and white images had narrated our history for decades. The transition to color was a radical leap that promised to add a new dimension to the world’s photographic archives. The technology Mespoulet and Mignon-Alba used was called autochrome color plates, an innovation by French inventors. This fledgling technology, a brainchild of the Lumière brothers, was indeed the harbinger of a vibrant era in photography.

The autochrome was a revolutionary process that used potato starches dyed red, green, and blue to create a filtering mosaic. Light passed through these microscopic filters when an image was taken, thereby capturing life in its full spectrum of color.

A Vivid Passage Through Ireland

For two months, Mespoulet and Mignon-Alba traversed the breadth and width of Ireland, documenting life as it unfolded before their lenses. They didn’t restrict themselves to capturing idyllic landscapes; instead, they delved deep into the social fabric of Ireland.

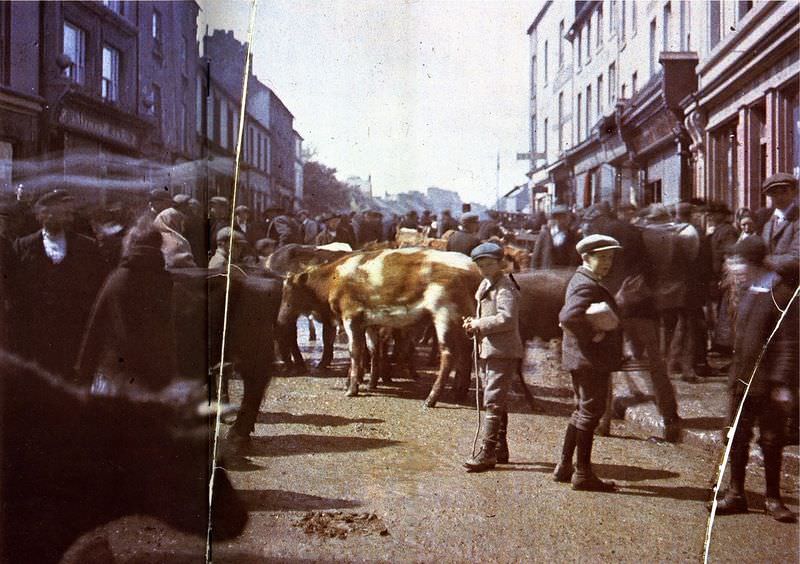

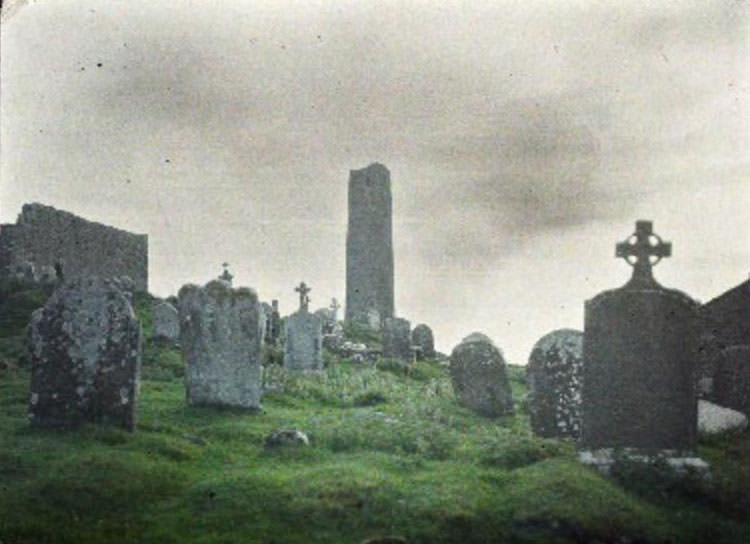

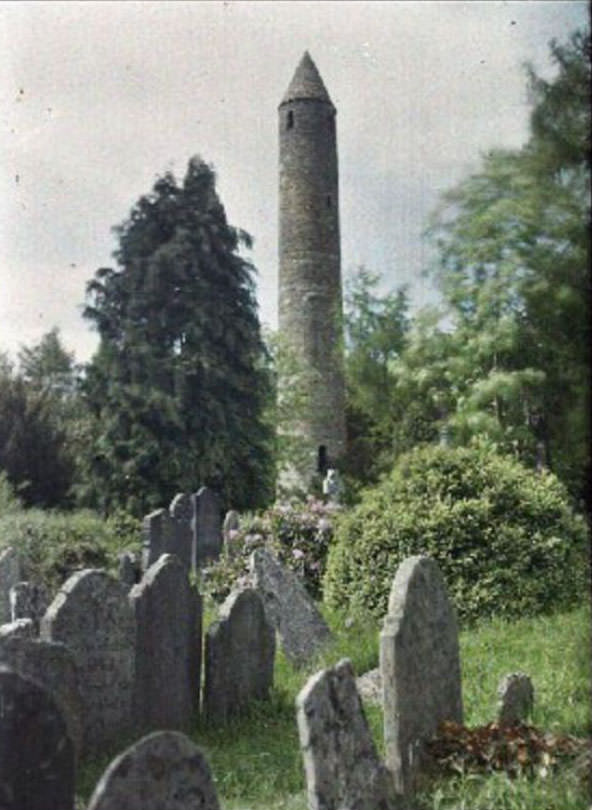

Their photographs reveal remote villages in the verdant countryside, offering an intimate look into the traditional Gaelic lifestyle that seemed untouched by the hands of time. They captured local folks in their everyday routines, children in play, women knitting, and farmers tending to their livestock. These images, tinged with shades of emerald green and rustic browns, evoke a sense of nostalgia for simpler times.

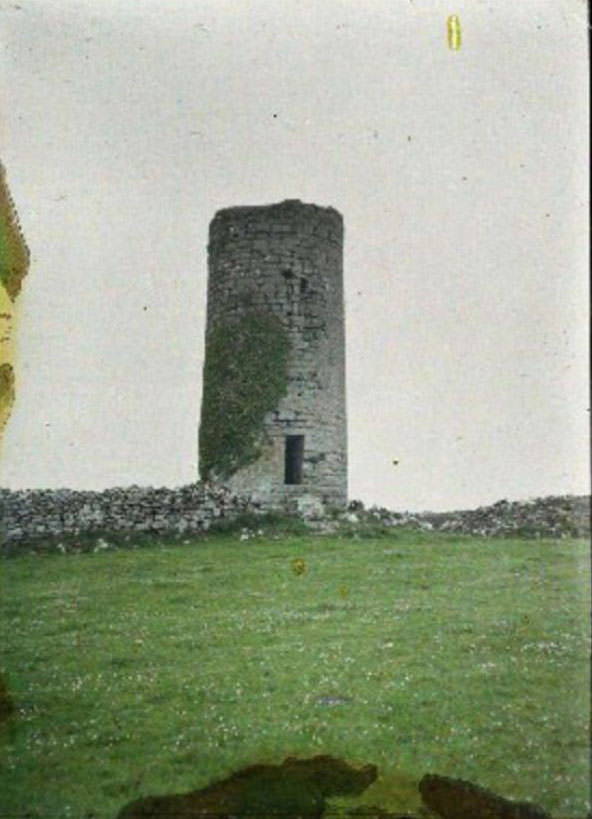

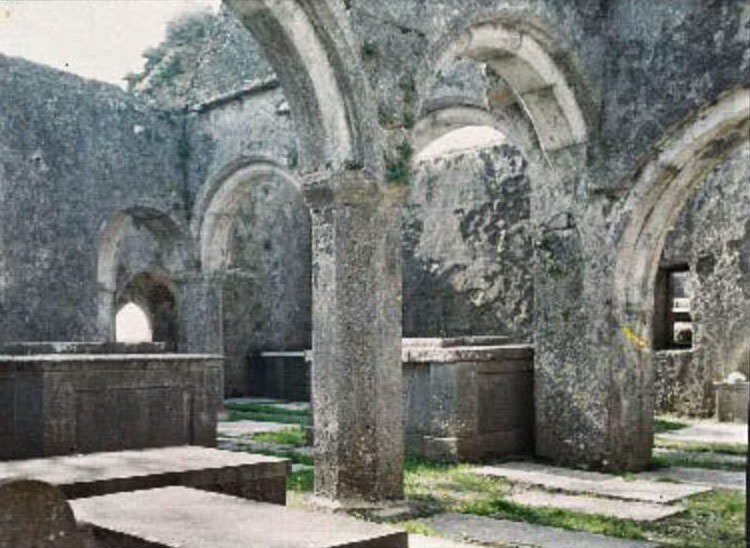

They also chronicled notable landmarks, such as ancient Celtic monuments, providing valuable visual references to Ireland’s rich history. Prominent Christian sites, such as timeless churches and tranquil cemeteries, too found a place in their colorful anthology. Their visual narrative stretched to the bustling streets of Galway City, bringing to light the contrast between the urban and rural Irish landscapes.