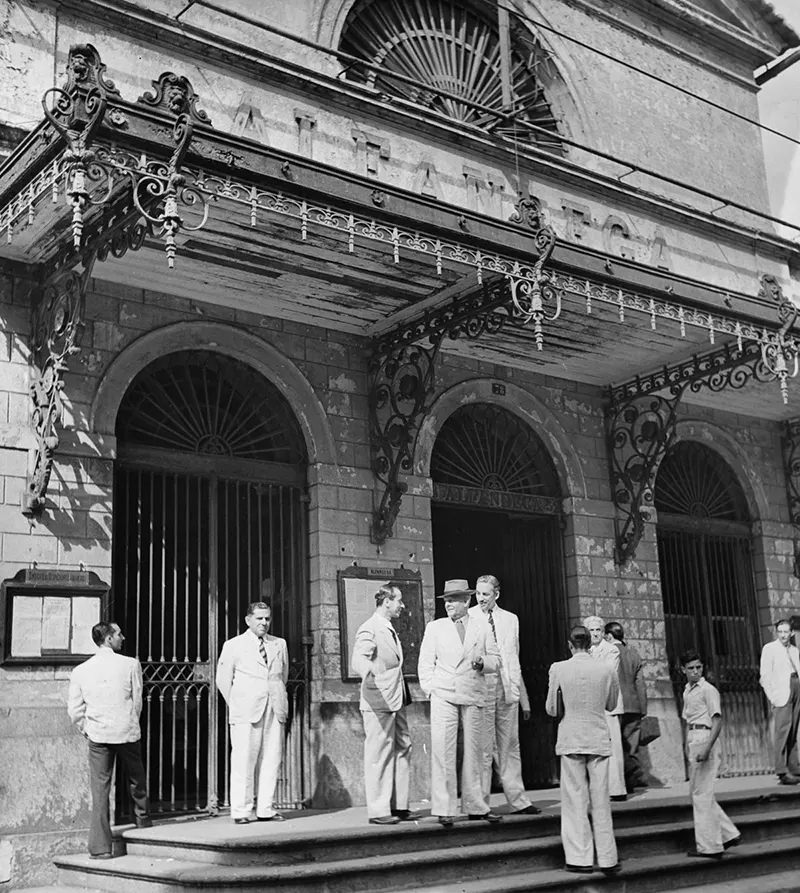

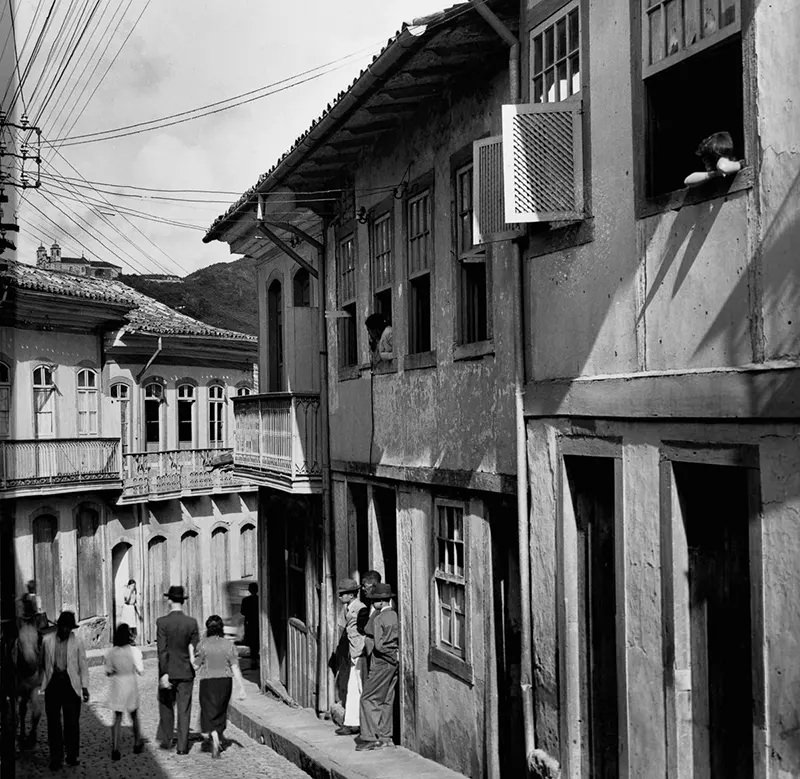

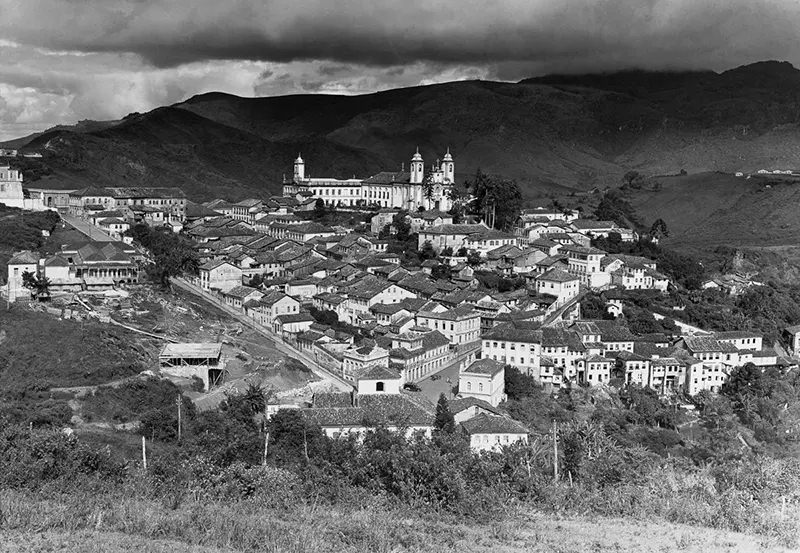

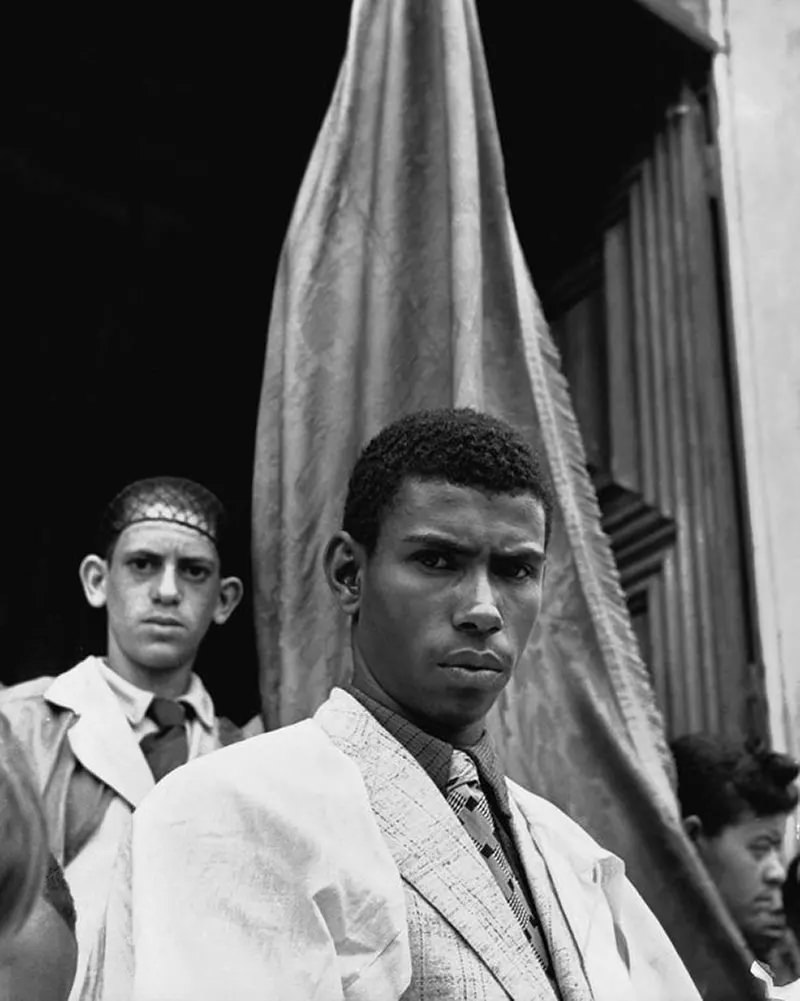

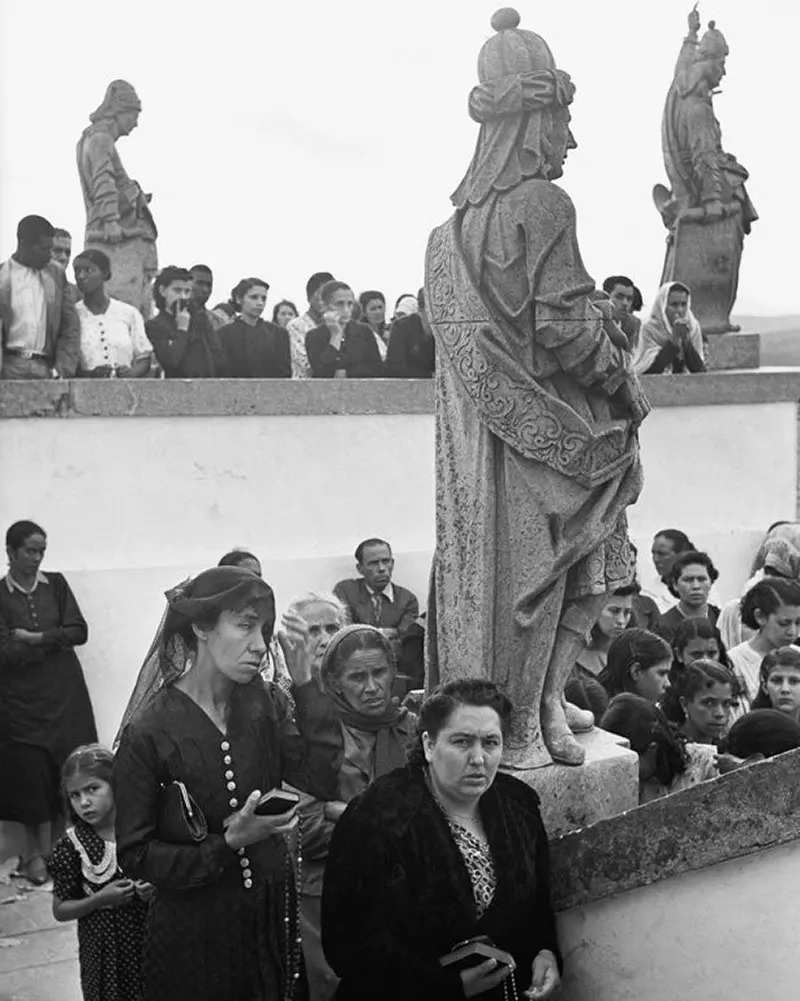

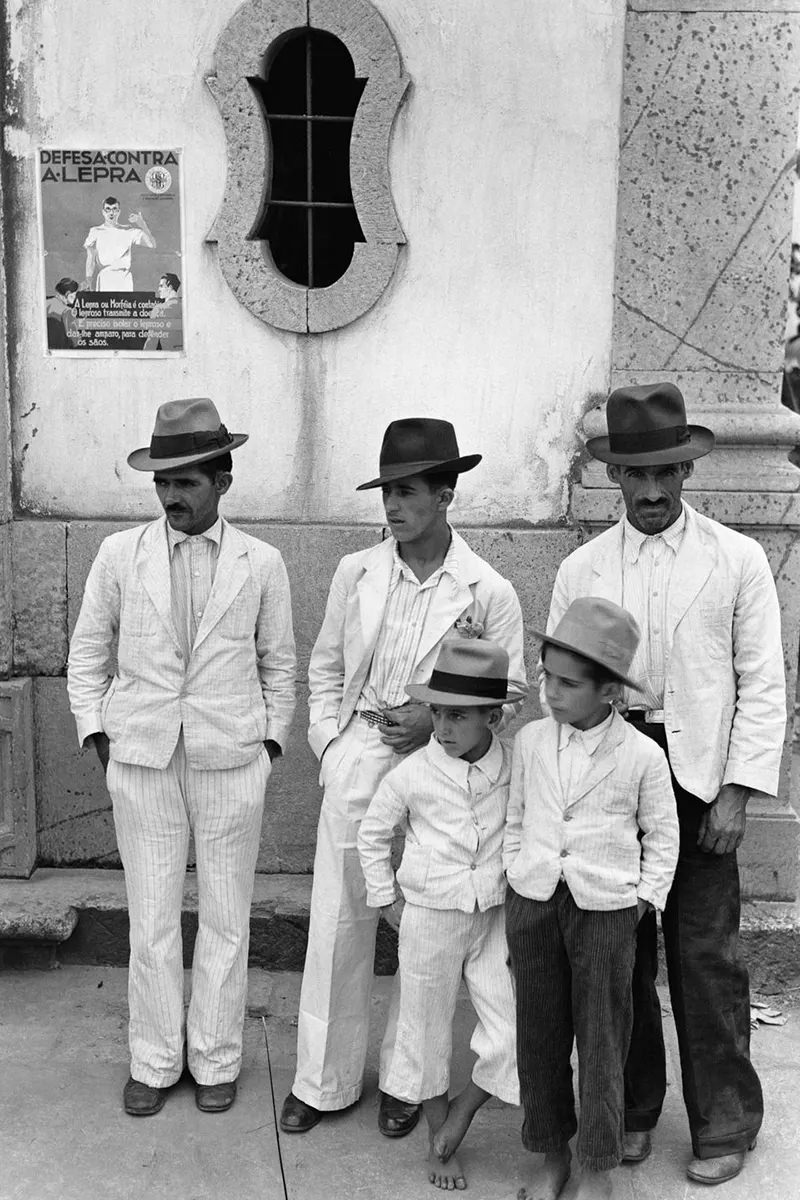

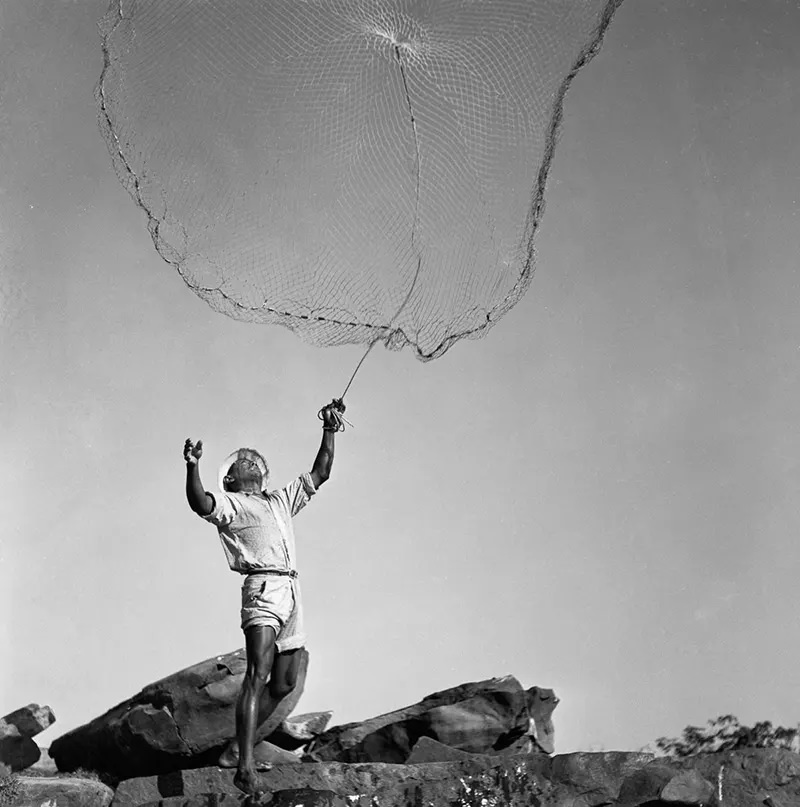

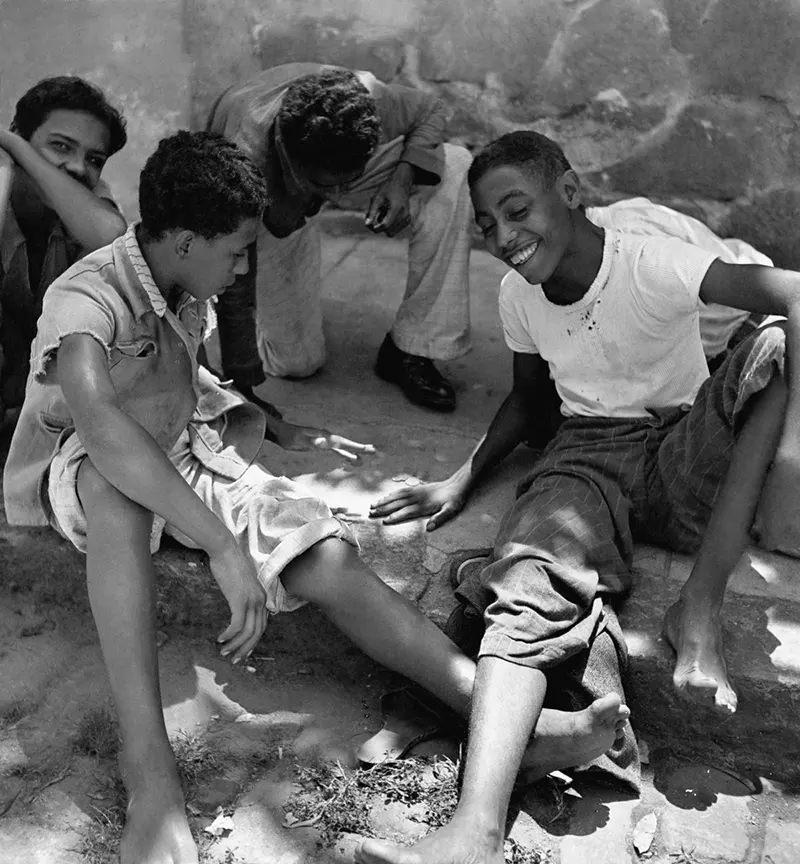

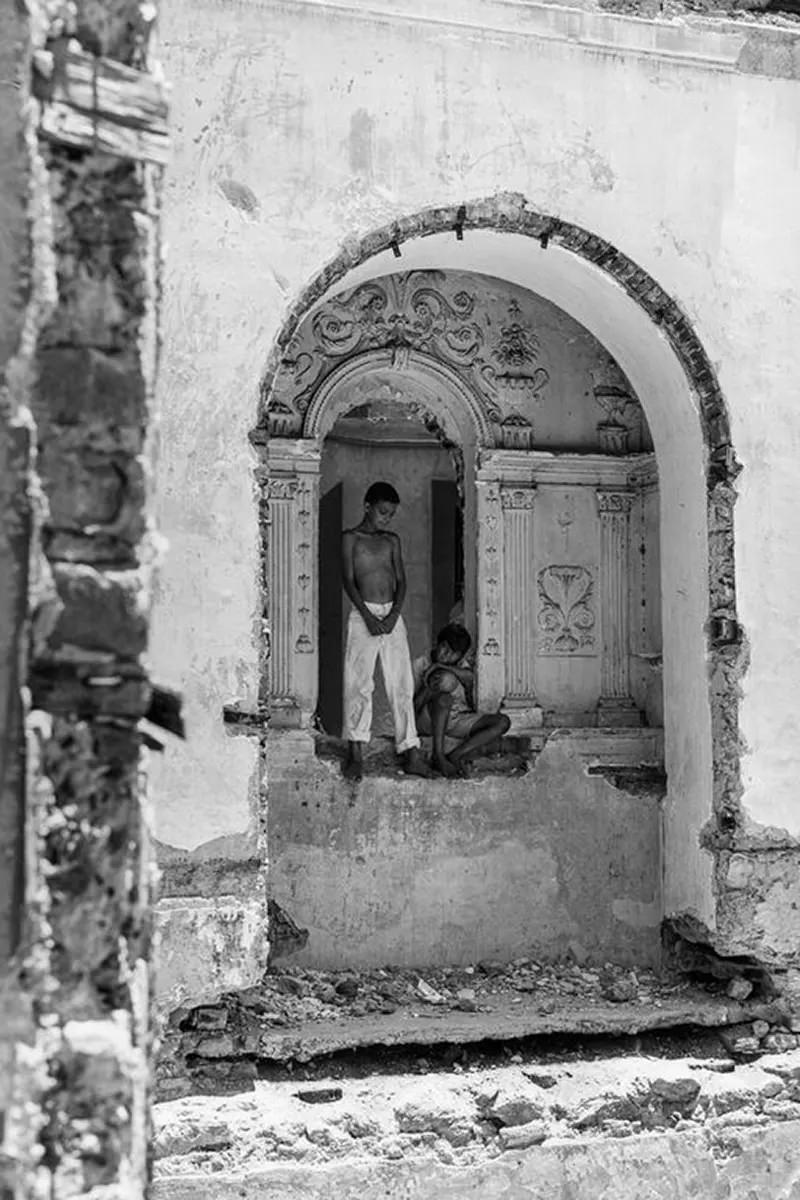

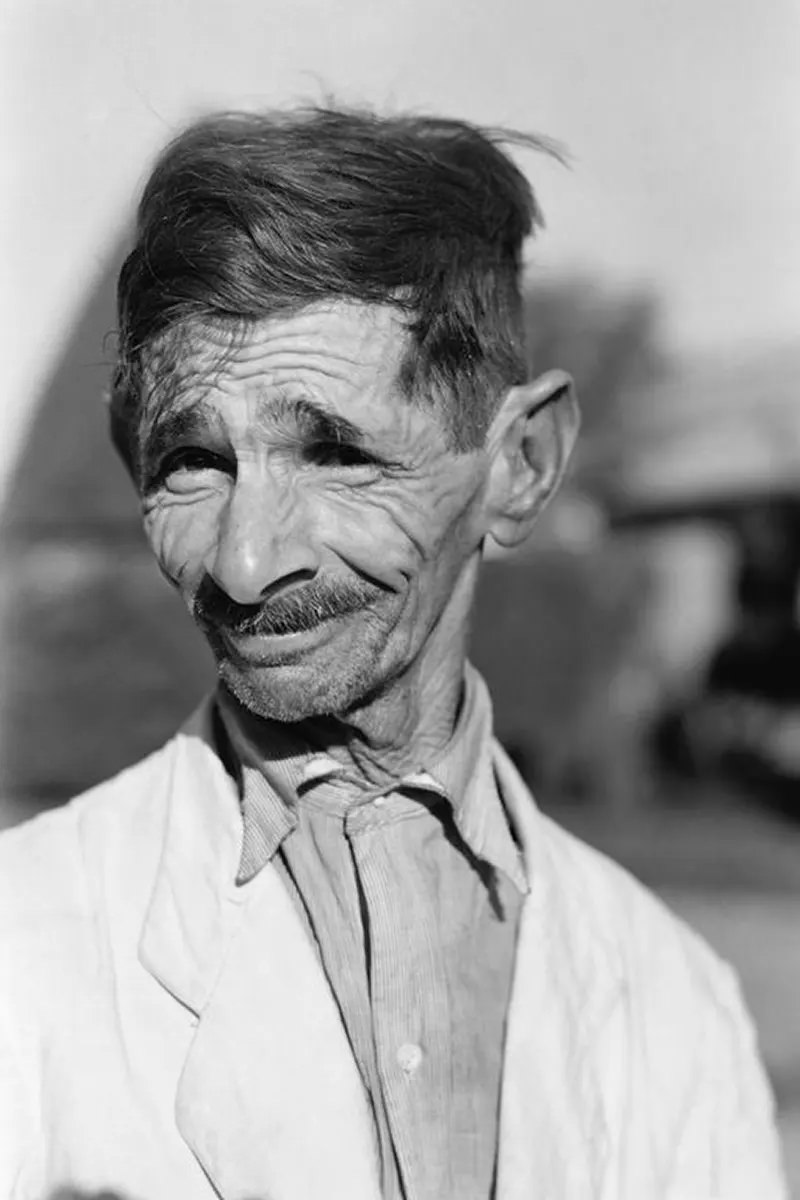

Photojournalist Genevieve Naylor, formerly of the Associated Press and the WPA, was sent to Brazil by Rockefeller’s agency in 1940 to support its wartime propaganda needs. As the Second World War gained steam, the State Department’s Office of Inter-American Affairs was charged with cultivating South American support for the Allies. Naylor’s collection of over a thousand photographs chronicles a period of Brazilian history that is rarely seen. Naylor’s photographs depict everyday life during a decade of modern Brazilian history that is little studied. The subjects include the rich and the poor, black Carnival dancers, fishermen, rural peasants from the interior, workers crammed into trolleys, and just ordinary Brazilians. Naylor’s equipment was modest because the film was rationed during the war. Because she did not have flash or studio lights, she carefully chose her shots, balancing spontaneity and composition. Of her work, nearly 1,350 photos survived and were preserved. After her return to the states in 1943, Naylor became only the second woman photographer to be given a one-woman show when her work was exhibited by New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Genevieve Naylor was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on February 2, 1915. Her father, Emmett Hay Naylor, a trade association lawyer and her mother, Ruth Houston Caldwell, were married on January 17, 1914. Genevieve’s middle name, Hay, references Abraham Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay. Genevieve’s parents divorced when she was 10 years old. After attending Miss Hall’s School, she attended the Music Box, an art school, where she studied painting at age 16. Genevieve met her teacher, Misha Reznikoff, at the Music Box. Two years later, in 1933, when Misha moved to New York, Genevieve soon followed, and they settled into the Bohemian lifestyle in Greenwich Village, where they lived in a studio apartment – a huge converted stable filled with colorful paintings, cigarette boxes, and parties that often lasted days with musicians, artists, and fans. She switched from painting to photography after attending an exhibit by photographer Berenice Abbott in 1934. In 1935, Naylor became Abbott’s apprentice, and they maintained a professional relationship until Naylor’s death.