Ontario’s government took advantage of a very rare event to make short-term financial gains during a time of economic hardship. The small Franco-Ontario hamlet of Corbeil, birthplace of the Quintuplets, became a booming tourist attraction with massive crowds and enormous profits. These five girls were raised in a zoo as babies.

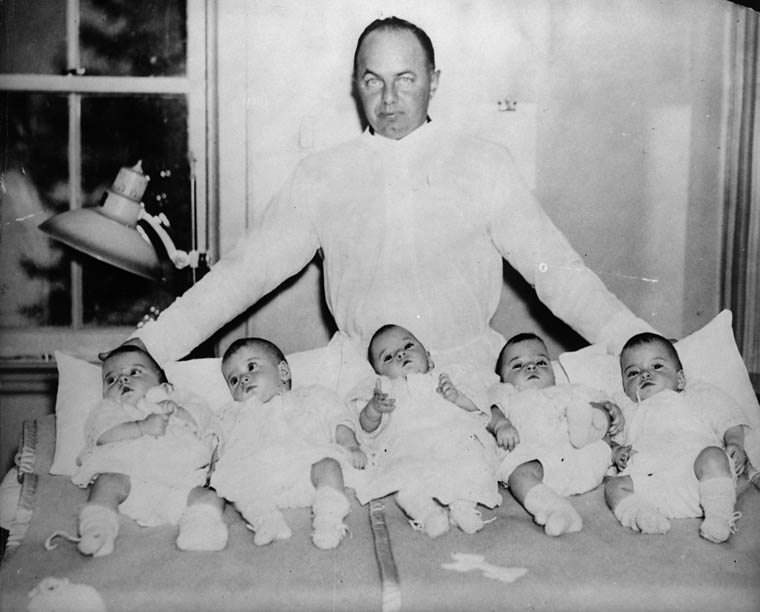

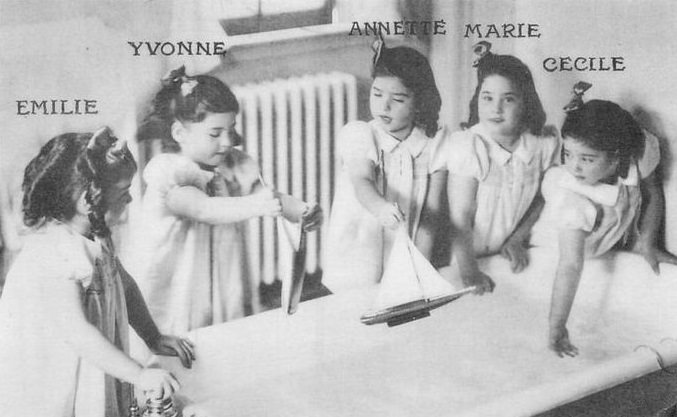

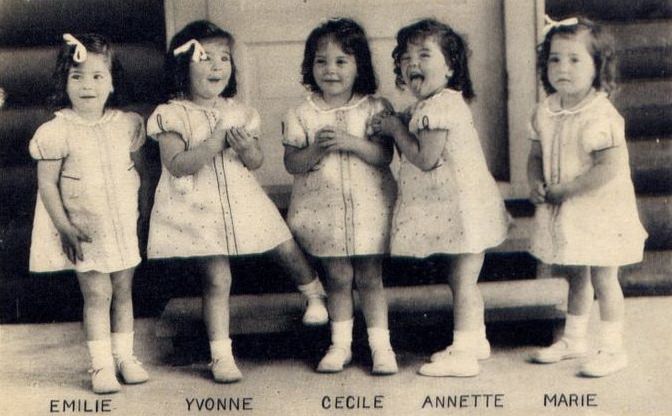

The Dionne quintuplets were born prematurely on May 28, 1934, near Callander, Ontario, Canada. There were 14 children born to the parents, 9 of whom were single births. The quintuplets were born to Elzire at the age of 24. While she suspected she was carrying twins, nobody was aware that quintuplets might be possible. Elzire was initially diagnosed with a “fetal abnormality”. Dr. Allan Roy Dafoe delivered the babies with the help of two midwives, Aunt Donalda and Madame Benoît Lebel, who were summoned by Oliva Dionne at midnight.

In total, the quintuplets weighed 13 pounds, 6 ounces (6.07 kg). The highest weight was 3 pounds 4 ounces and the lowest weight was 2 pounds 4 ounces. The weights and measurements of each individual were not recorded. Immediately, the quintuplets were wrapped in cotton sheets and old napkins and laid in the corner of the bed. Elzire went into shock, but she recovered in two hours. This set of “quints” had a unique distinction in that they were the first medically and genetically documented set to survive; no other quintuplet set had ever survived. The Dionne set had a sixth member that aborted during the third month of pregnancy. The University of Toronto studied the quintuplets biologically, psychologically, and dentally. According to the biological study, the set originated from one fertilized egg. Dionne quintuplets were formed by repeated twinnings of an embryo; therefore, six embryos were produced and five infants survived to birth.

An inquiry from Oliva’s brother to the local newspaper editor about how much he would charge for an announcement of five babies at a single birth sparked news of the unusual birth. Several individuals sent supplies and well-wishes (one letter from Appalachia recommends a tiny dose of burnt whiskey to prevent diarrhea); one hospital sent two incubators. A number of women offered their breast milk to the quintuplets as well. In exchange for their donations, the women received ten cents per ounce of milk. As a result, women were able to contribute to household income during the Great Depression. The milk was preserved and sent by train to the quintuplets once it was received. Every morning, Dr. Alan Brown of Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children delivered twenty-eight ounces of breast milk to the quintuplets.

During their childhood, the Quints lived in terrible conditions and were abused by the provincial government for publicity and funds. When the sisters were four months old, the Red Cross took custody of them and paid for their care and built a hospital for them. The Dionnes made a stage appearance as “Parents of the World Famous Babies” in Chicago in February 1935. Mitchell Hepburn, the Premier of Ontario at the time, extended the guardianship based on the Dionne vaudeville trip. The Dionne Quintuplets Act, passed in March 1935, officially made the girls wards of the Crown and extended guardianship to the age of eighteen to save them from further exploitation.

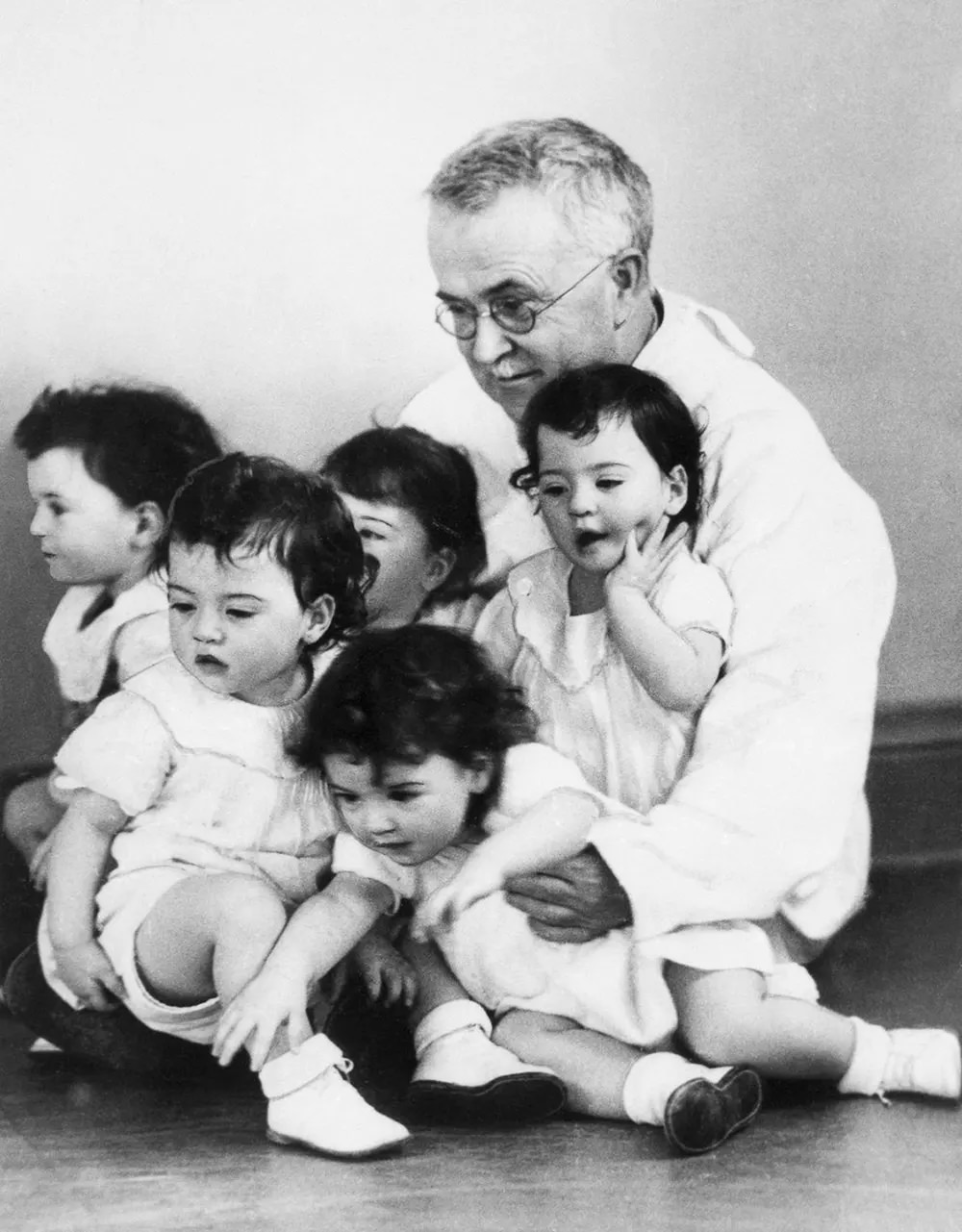

The government recognized the sisters’ public interest and set up a tourist industry around them. They were made wards of the provincial Crown, planned until they reached the age of 18. Their new caregivers and the five girls were housed in the Dafoe Hospital and Nursery across the street from their birthplaces. On September 21, 1934, the girls were moved from the farmhouse to the nursery, where they lived for nine years. The compound had an outdoor playground designed for public observation. Tourists were able to observe the sisters behind one-way screens through a covered arcade. Screens installed in one direction prevent distractions and noise. The facility was funded by a Red Cross fundraiser. Several times a day, the sisters were brought to the playground in front of the crowd.

The Dionne sisters were constantly tested, studied, and examined, and everything was documented. They lived in a somewhat rigid lifestyle at the compound. The children did not have to participate in chores and had private tutoring in the same building where they lived. Their exposure to the world outside the compound was limited to the daily rounds of tourists, who were generally heard but not seen from the sisters’ perspective. There was also occasional contact between them and their parents and siblings across the street. In the beginning, visitors watched the quintuplets through a hospital window. When visitors came, the quintuplets became excited, but became irritated when they left.

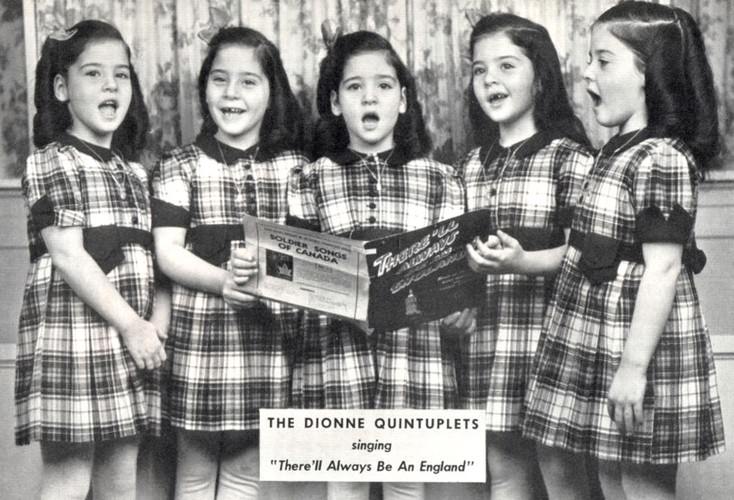

The observatory opened on Canada Day in 1936. There were thousands of tourists and hundreds of cars gathered to see the sisters. There were rules for visitors, including staying silent and not talking to the girls, moving to avoid obstructions, not taking photos if the weather was bad, and not speaking to the girls. Each day, about 3,000 people visited the observation gallery surrounding the outdoor playground to observe the Dionne sisters. Between 1936 and 1943, almost 3,000,000 people walked through the gallery. The area became known as Quintland because Oliva Dionne ran a souvenir shop and a woolen store opposite the nursery. There were souvenirs with pictures of the five sisters, including autographs, framed photographs, spoons, cups, plates, plaques, candy bars, books, postcards, and dolls.

In 1939, Dr. Dafoe resigned as guardian, and Oliva Dionne was gaining more support for reuniting the family. They were reunited because their parents worked hard to regain custody. In 1942, the Dionne family moved into the nursery with the quintuplets while they awaited the completion of their new home. The Dionne family moved into their new home in November 1943. The quintuplets used their fundraising funds to build the yellow brick, 20-room mansion. Their house was nicknamed “The Big House” because it was equipped with many amenities that were considered luxuries at the time, such as electric lighting, hot water, and telephones.

After turning 18 in 1952, the quintuplets left the family home and had little contact with their parents. There were three women who married and had children: Marie had two daughters, Annette had three sons, and Cécile had five children, including one who died in infancy and twins Bruno and Bertrand. Émilie devoted her brief life to becoming a nun. Yvonne completed nursing school before turning to sculpture and later becoming a librarian. Émilie died at the age of 20 as a result of a seizure. Marie lived alone in an apartment in 1970, and her sisters were concerned after not hearing from her for several days. Marie had been dead for days when her doctor arrived at her home and found her in bed. Cécile and Annette divorced, and by the 1990s, the three surviving sisters lived in Saint-Bruno-de-Montarville, a suburb of Montreal.