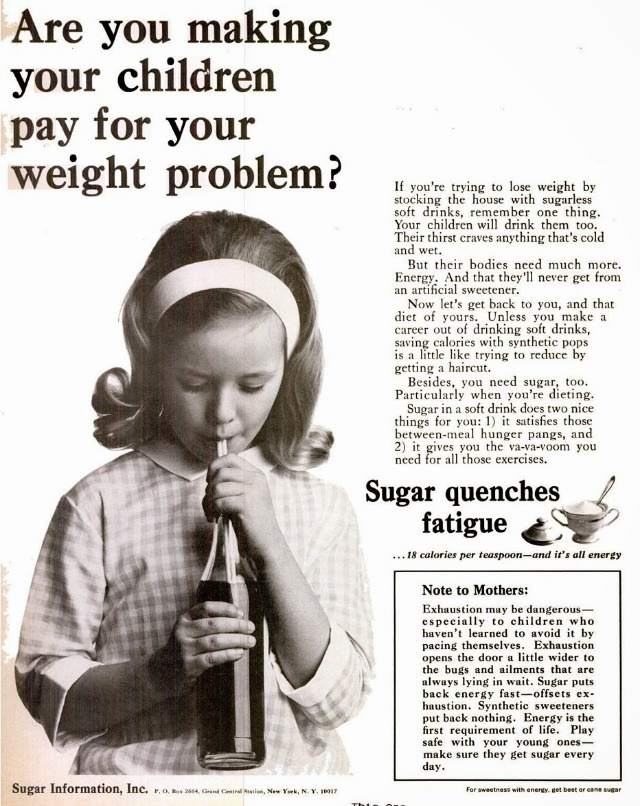

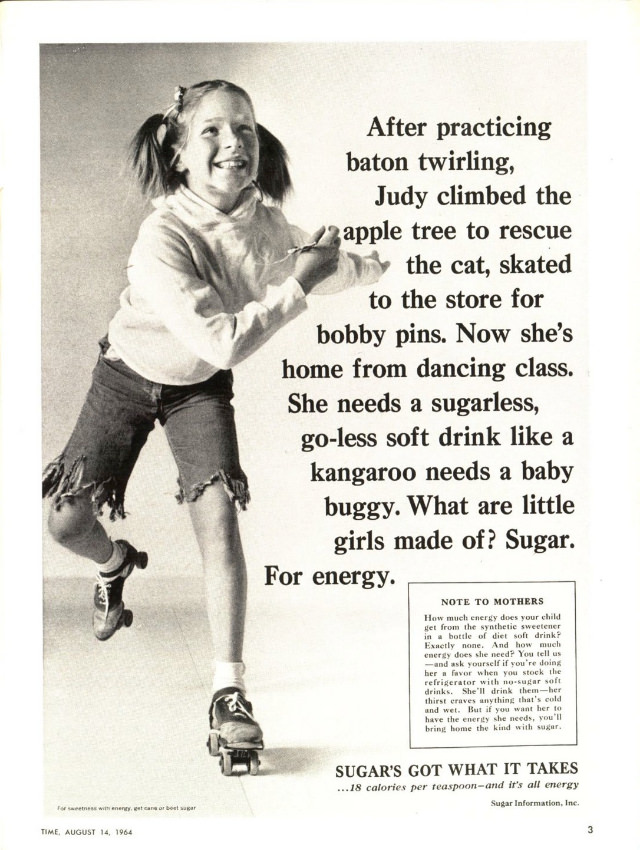

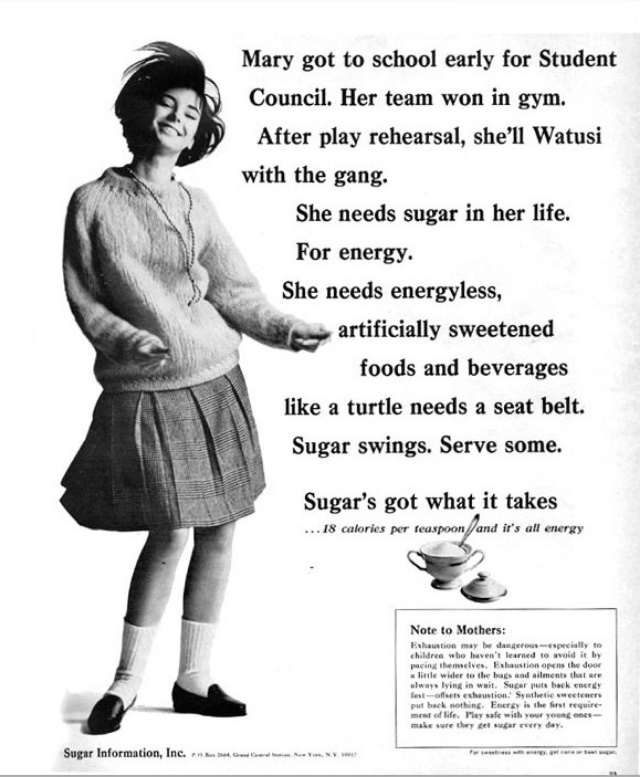

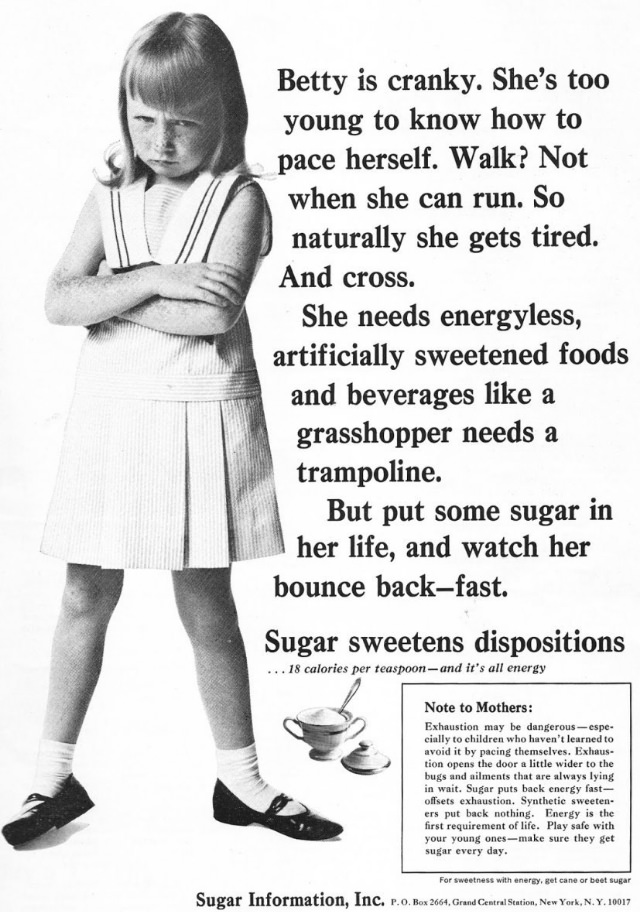

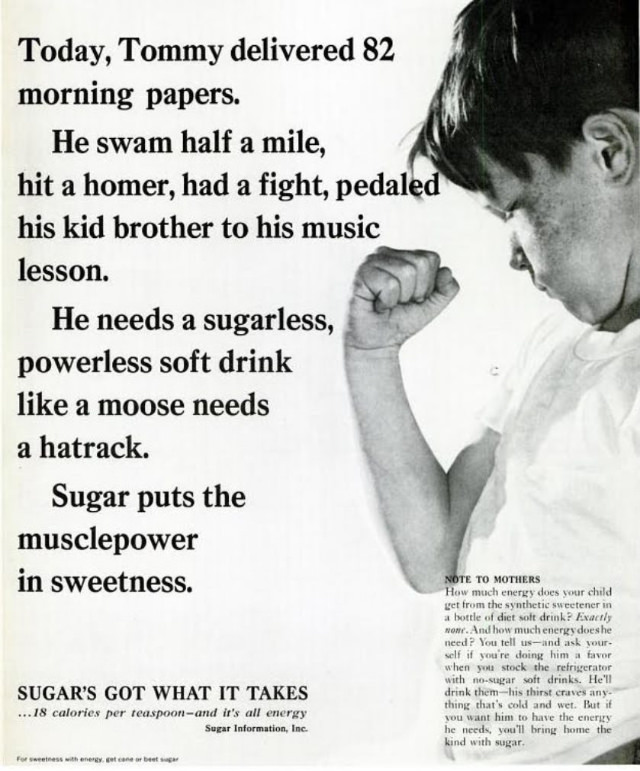

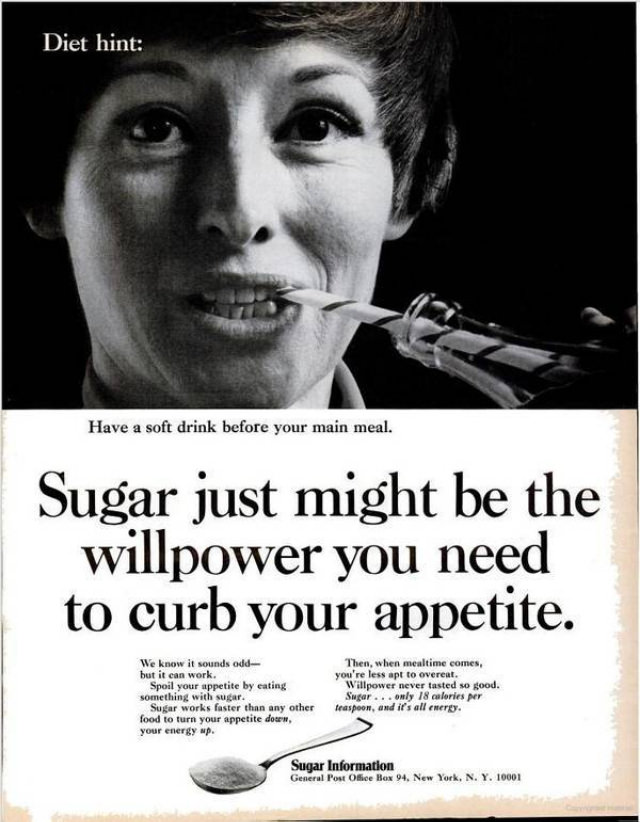

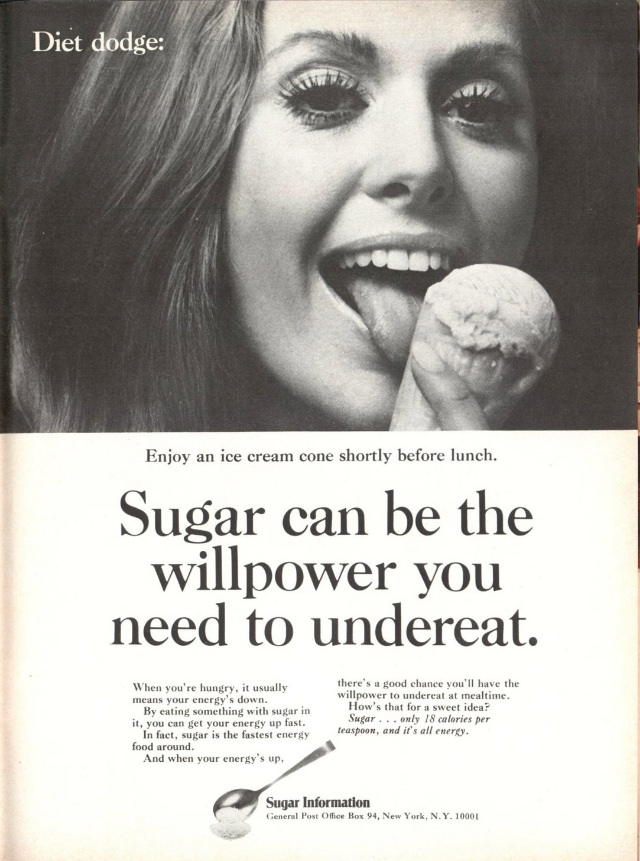

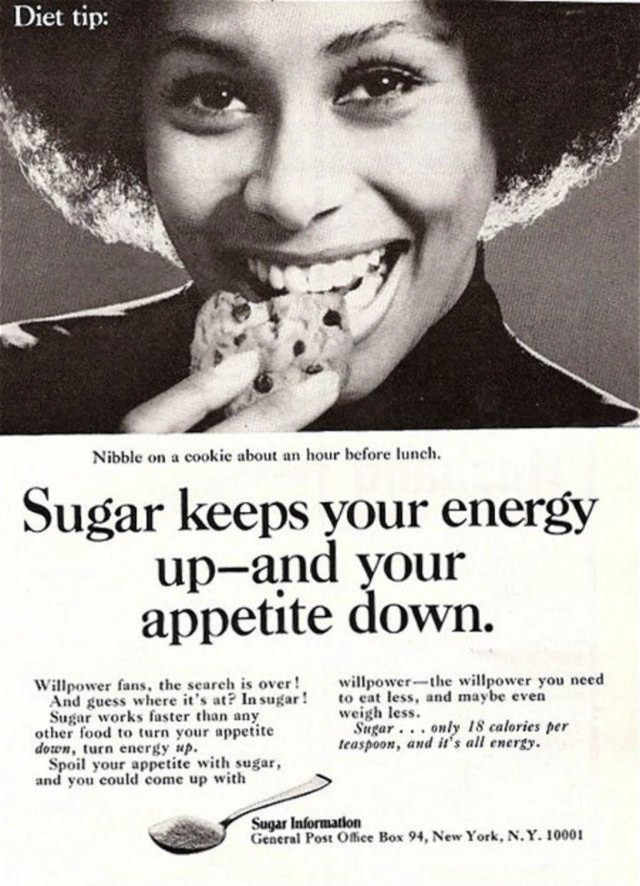

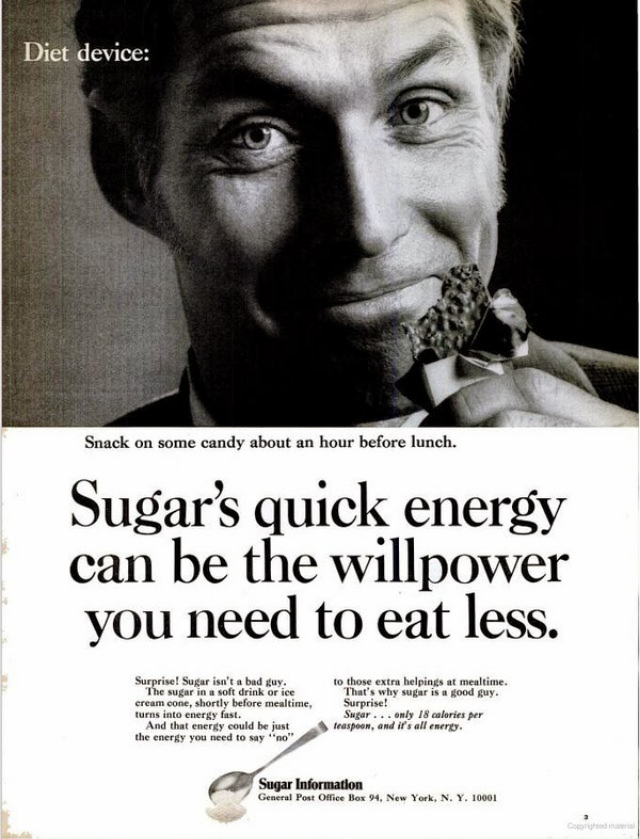

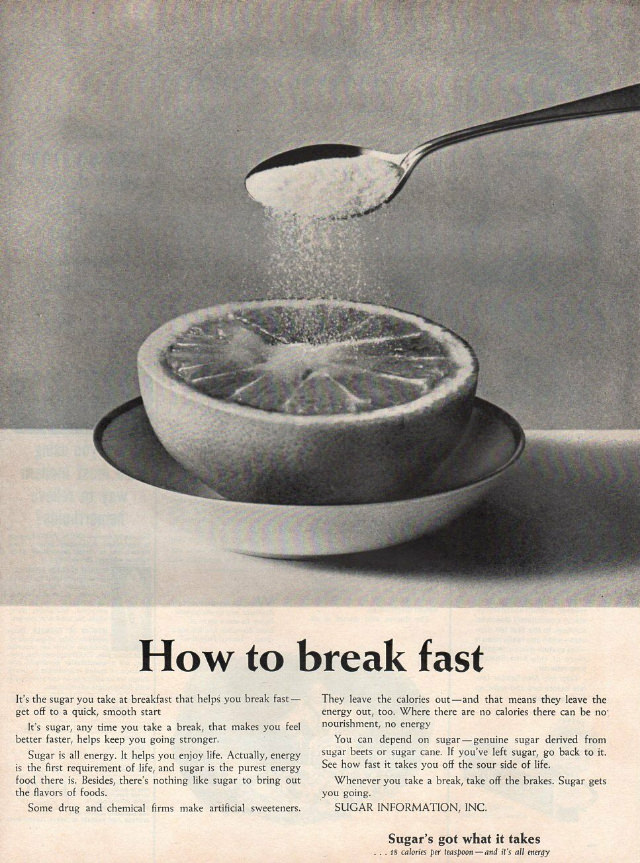

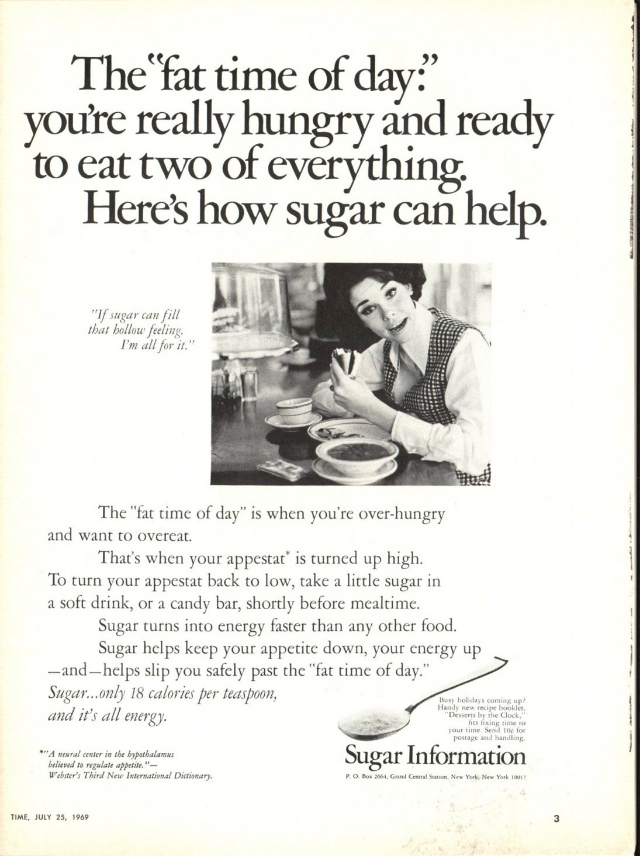

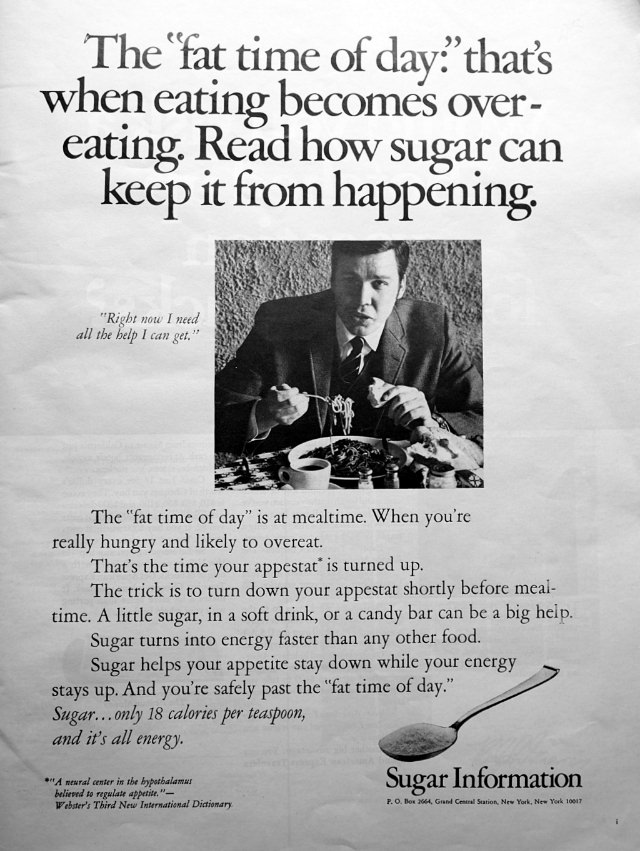

In the mid-1950s, health researchers began spreading the idea that sugar can contribute to weight gain, which led to the now-strange advertisements. Sugar firms increased their advertising budgets in response. Sugar Information Inc. even won an award in 1955 for “public interest advertising.” That process began to ramp up in the mid-1960s, mainly as diet soda started to gain market share. Sugar group ads countered that consumers should be aware diet sodas won’t help them lose weight since they aren’t satisfying or energizing in the same way that full-sugar drinks are.

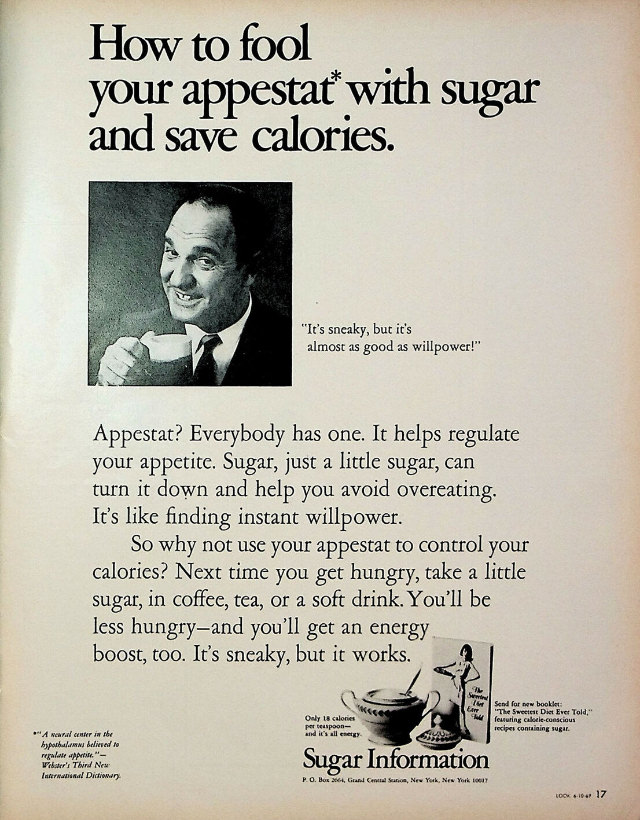

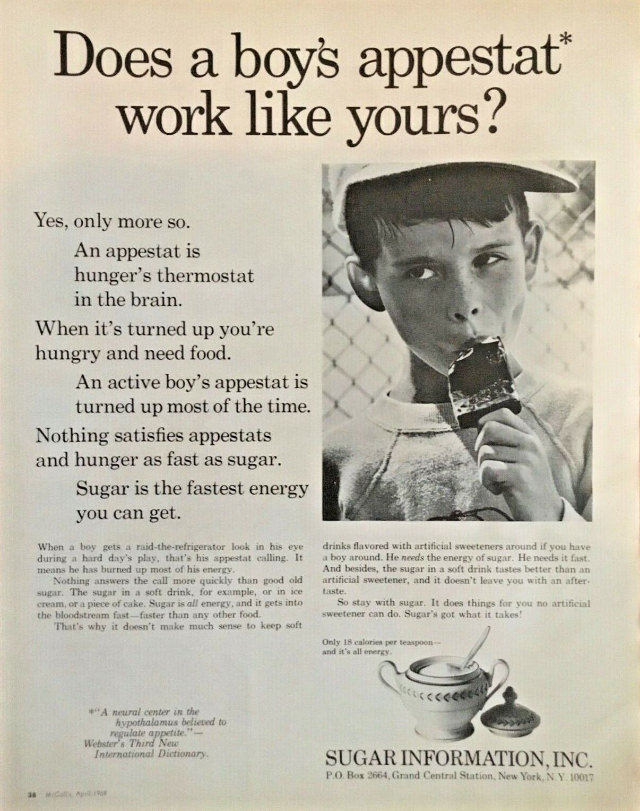

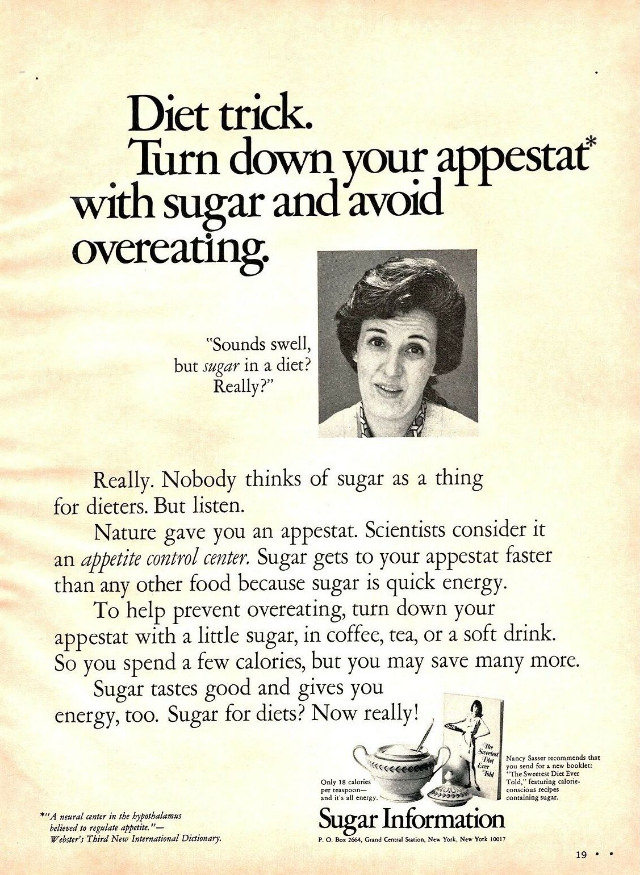

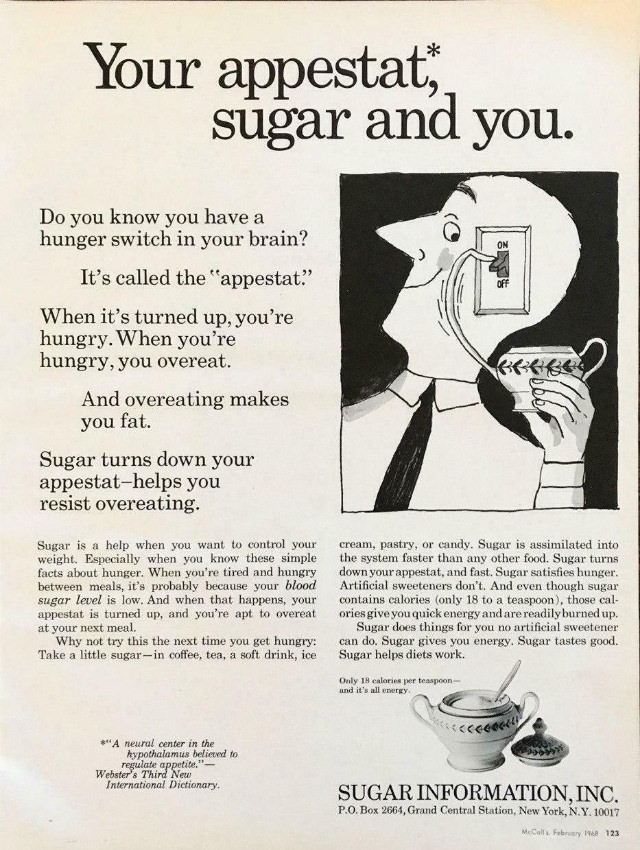

The advertising campaign was primarily based on the mid-century health concept of the “appestat,” which had been described by a nutritionist in a 1952 book on weight loss. A problem with “the individual’s appetite-regulating mechanism” could leave people unsatisfied and thus likely to overeat. In contrast to replacements, natural sugar can reduce the appetite and provide energy.

However, the Federal Trade Commission stepped in to stop the ads by December of 1971, citing that the advertisements implied that eating more sugar would mean eating fewer calories overall, but that was not true. The FTC began to ask advertisers for evidence supporting their claims during this time. Initially, the Sugar Association said the ads were actually full of good health advice, which the FTC misinterpreted. By the end of 1972, the sugar industry group agreed to spend upwards of $150,000 to run ads that clarified the earlier campaign.