Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw (or Kwakiutl) are Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Most of them live on northern Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland and islands near Johnstone Strait and Queen Charlotte Strait. In the past, there were approximately 28 communities speaking dialects of Kwak’wala – the Kwakwaka’wakw language – but some of these died out or joined others, to the point where the number of communities is approximately in half. From the late 18th century onward, Europeans applied the name of one band, the Kwakiutl, to the entire group, a tradition that persists today. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Kwak’wala-speaking area has been inhabited for 8,000 years. The Kwakwaka’wakw fished, hunted, and gathered following the seasons before contact with Europeans, resulting in a plentiful supply of preserved food. As a result, they returned to their winter villages to perform ceremonies and engage in artistic endeavors for several months.

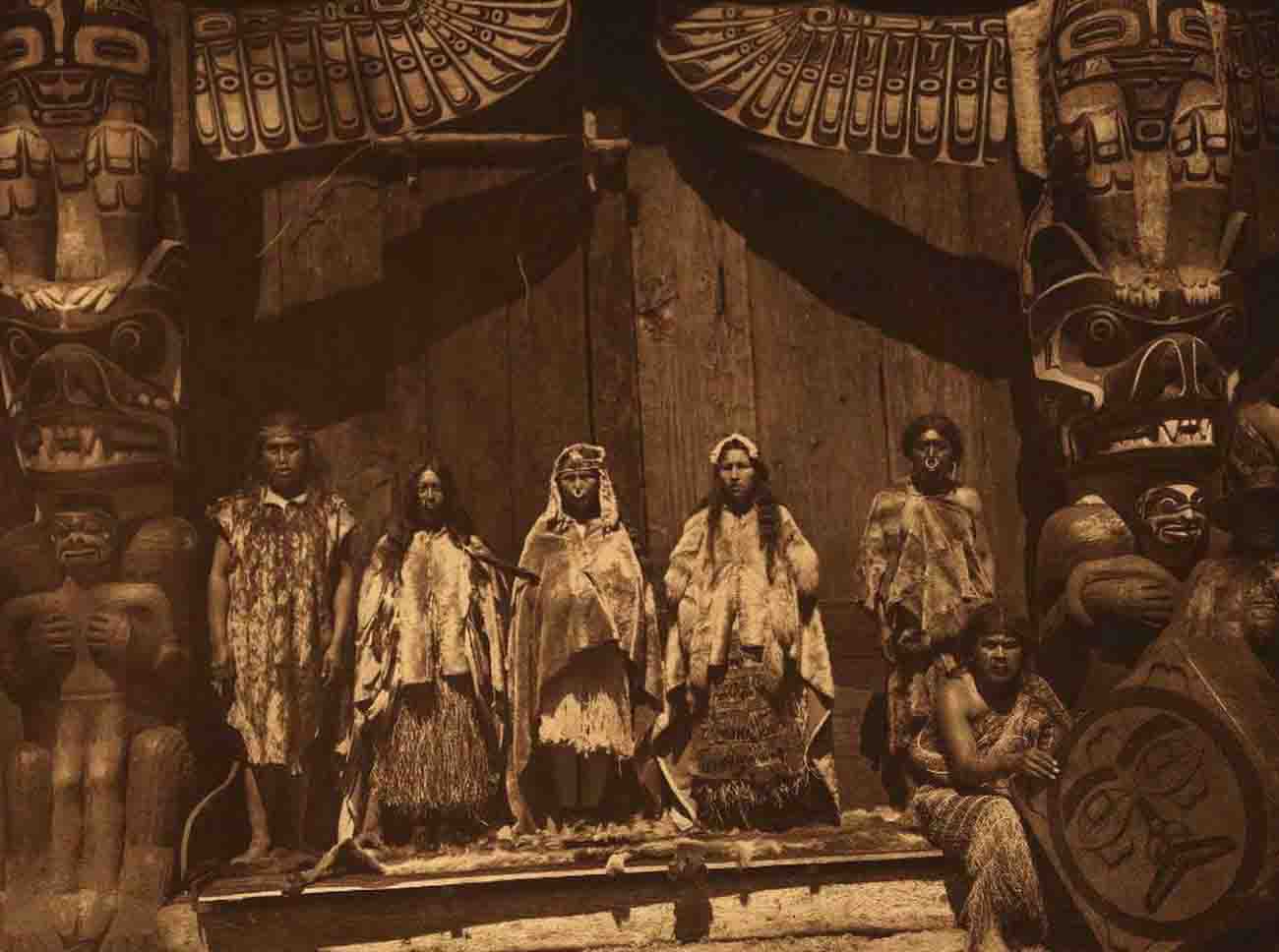

The first documented contact with Westerners occurred in 1792 during the expedition led by English officer Captain George Vancouver, followed by the settlement of European colonies on Canada’s West Coast. The Kwakwaka’wakw population dropped by up to 75% between 1830 and 1880 due to diseases brought by settlers. Their oral history claims their ancestors (ʼnaʼmima) arrived by land, sea, or underground in the form of animals. The ancestral animal that came at a particular spot shed its animal appearance and became human. A few animals that feature in these origin myths include Thunderbird, his brother Kolas, seagulls, orcas, grizzlies, and chief ghosts. The ancestors of some people come from distant places and have human origins. Potlatch ceremonies featured elaborate weaving and woodwork, and wealth was exhibited and traded as enslaved people and material goods. Franz Boas studied these customs in depth.

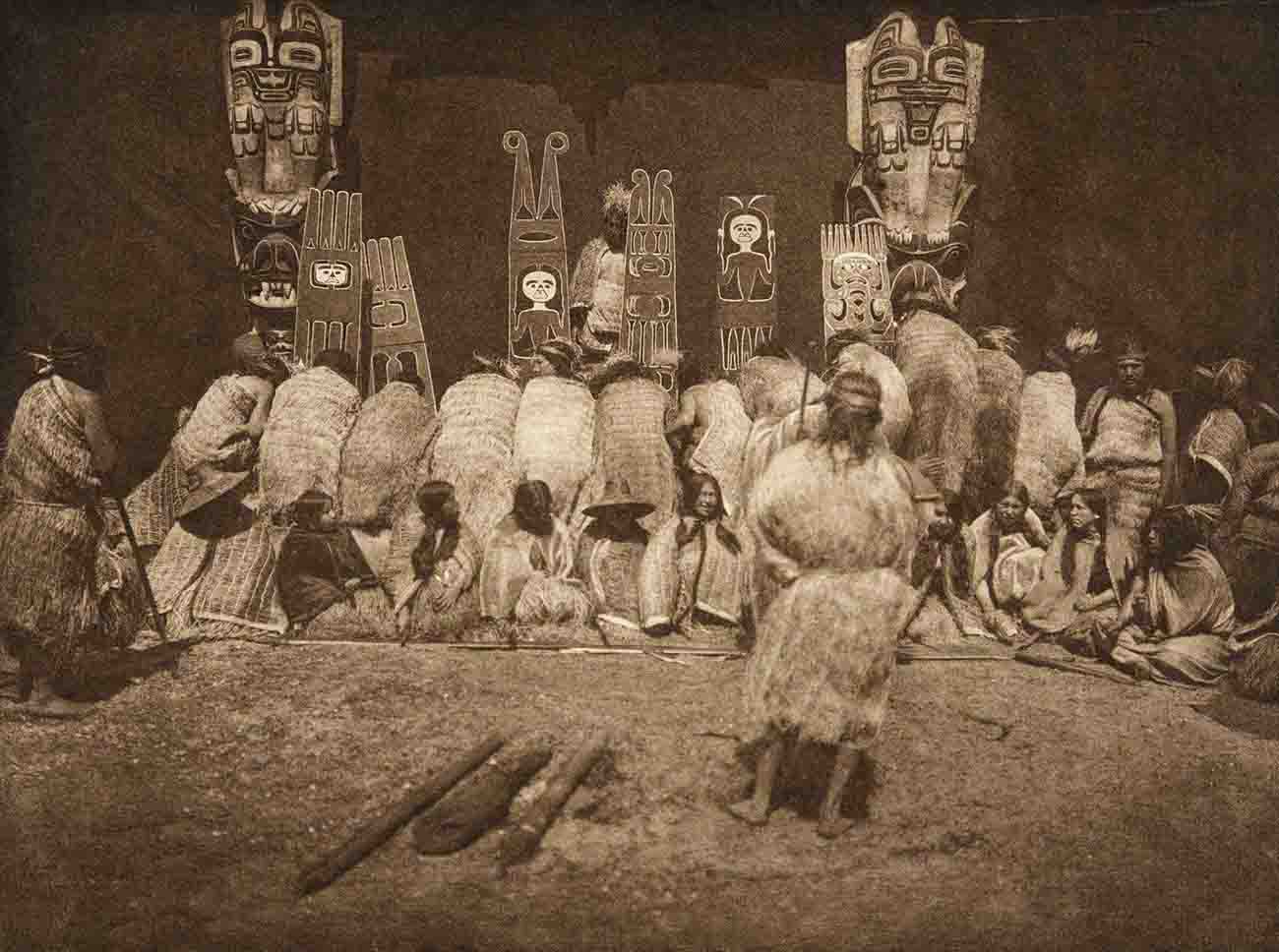

Contrary to most non-native societies, wealth and status were determined by how much you gave away, not how much you had. Giving away your wealth was an essential part of a potlatch. Potlatch culture is well known and studied in the Northwest. The Kwakwakaʼwakw still practice it, as do their neighbors known for their lavish artwork. It details the incredible artwork and legends associated with the potlatch, high politics, and the great wealth and power of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw chiefs in Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch.

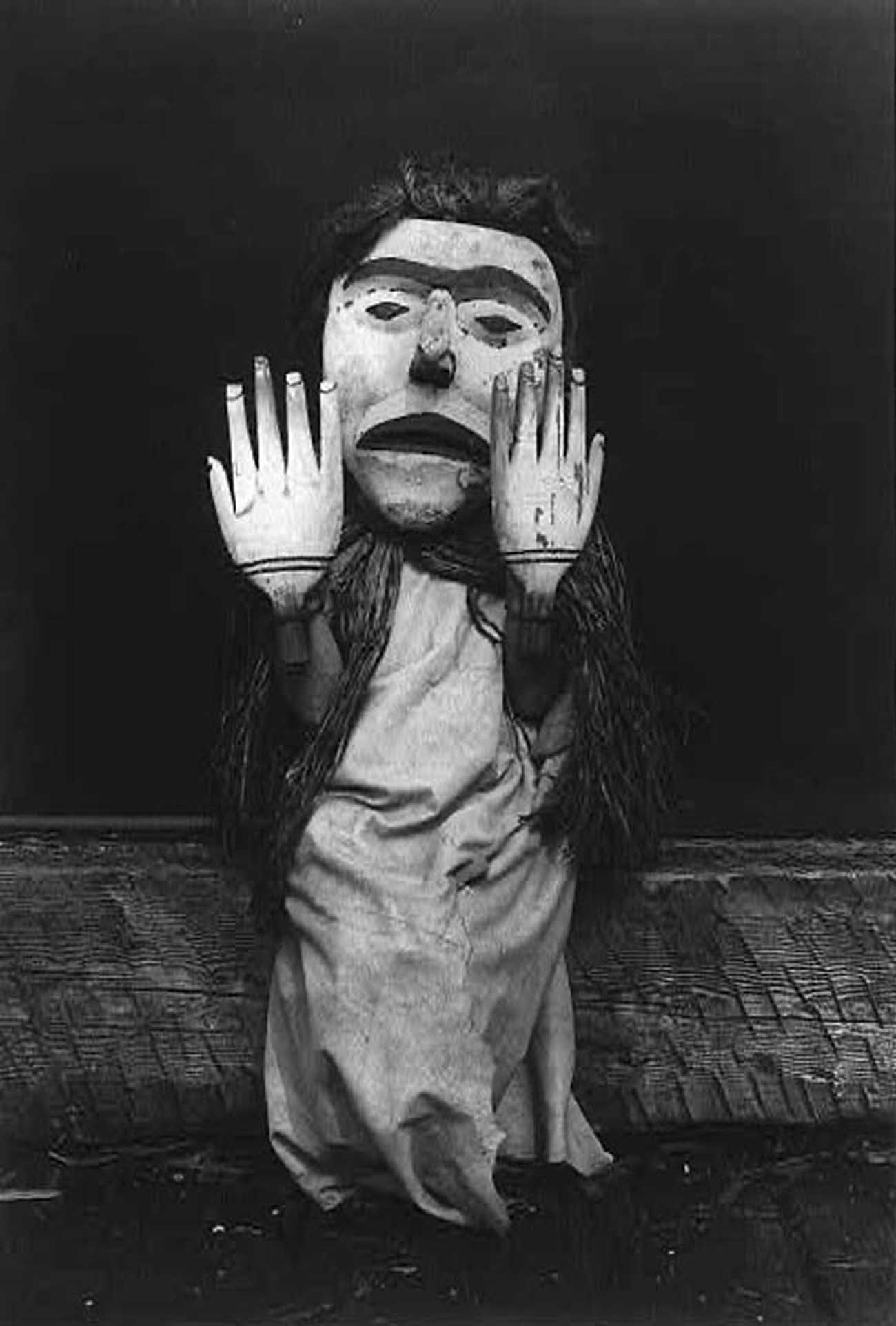

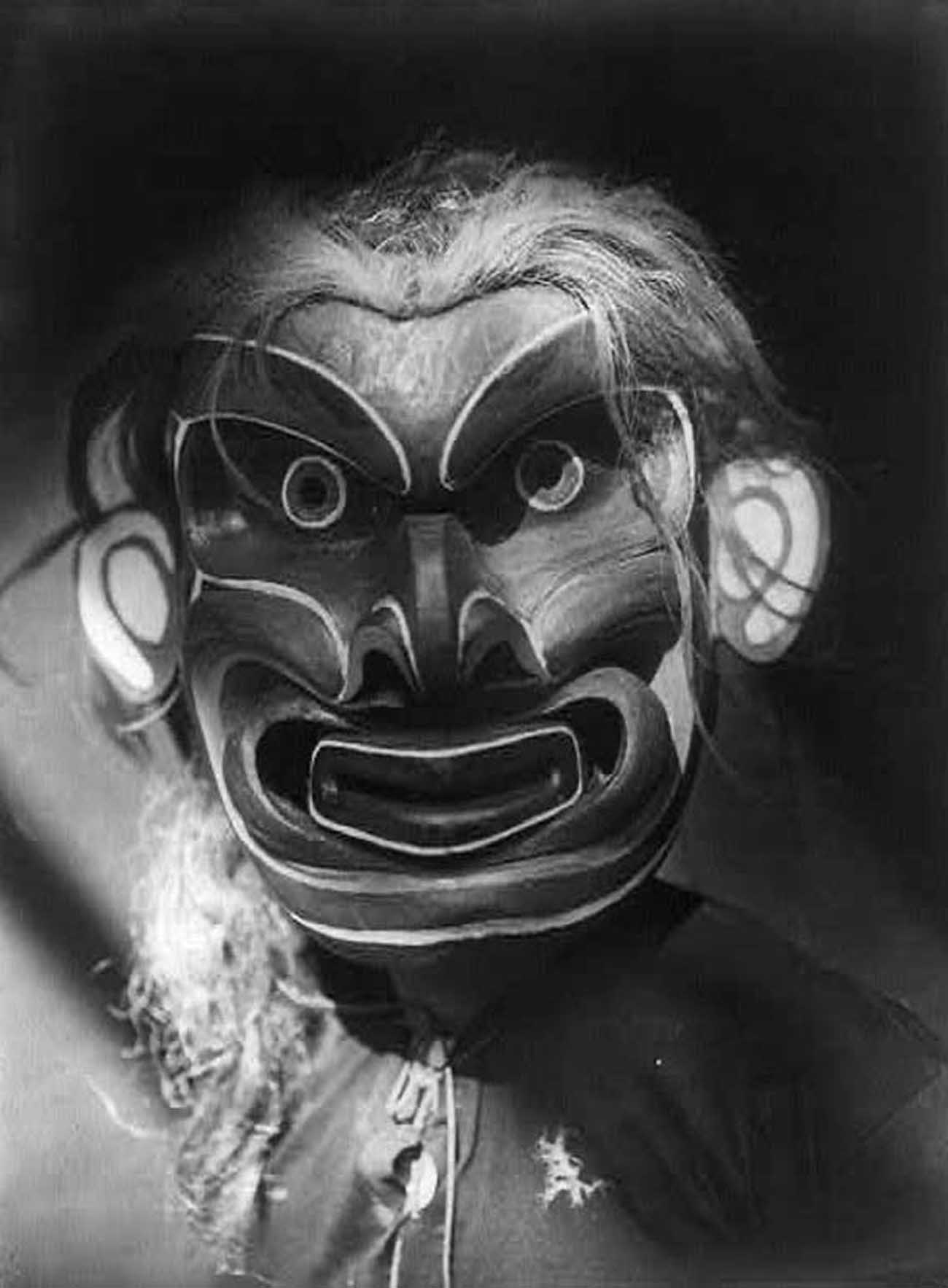

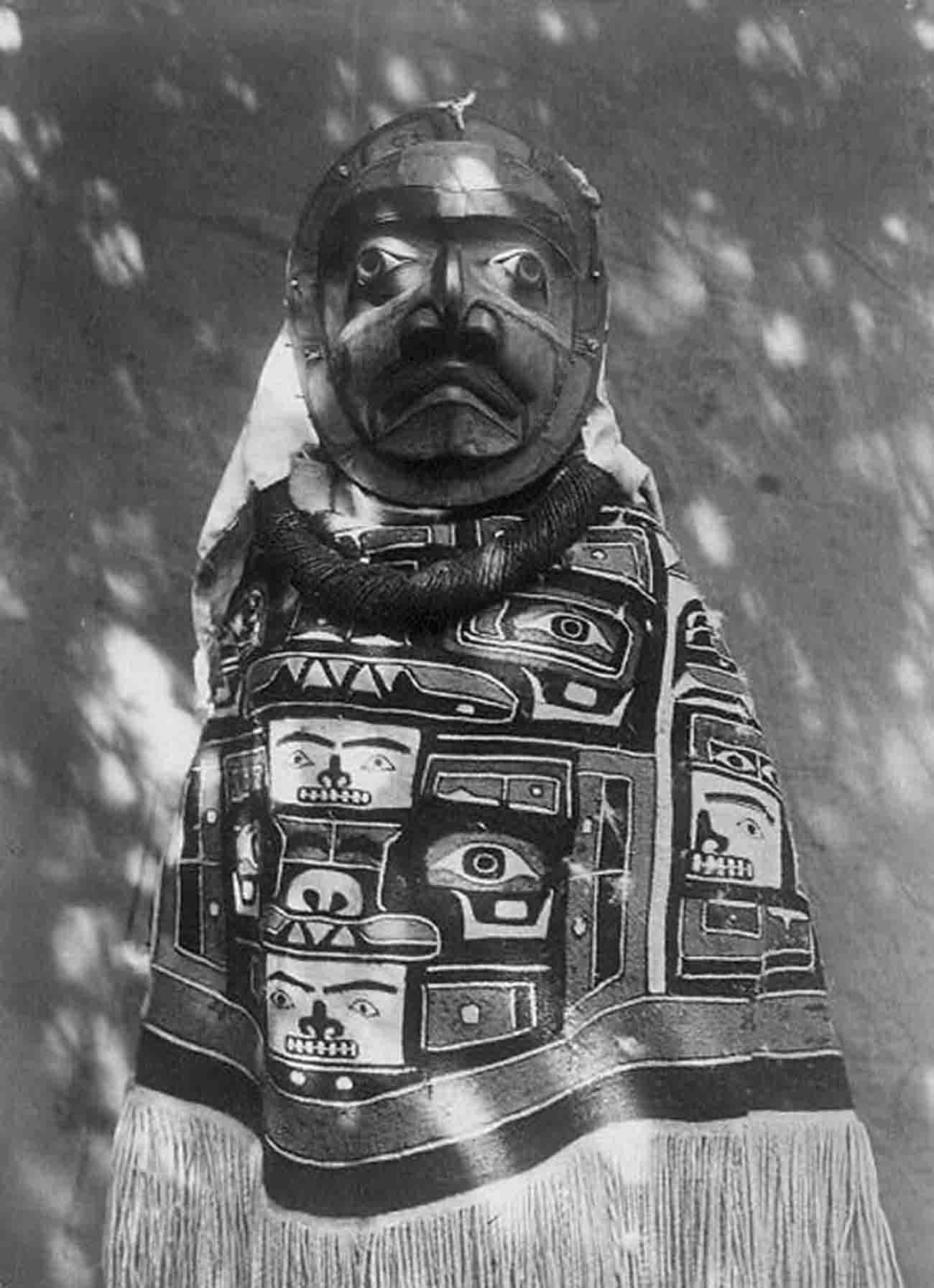

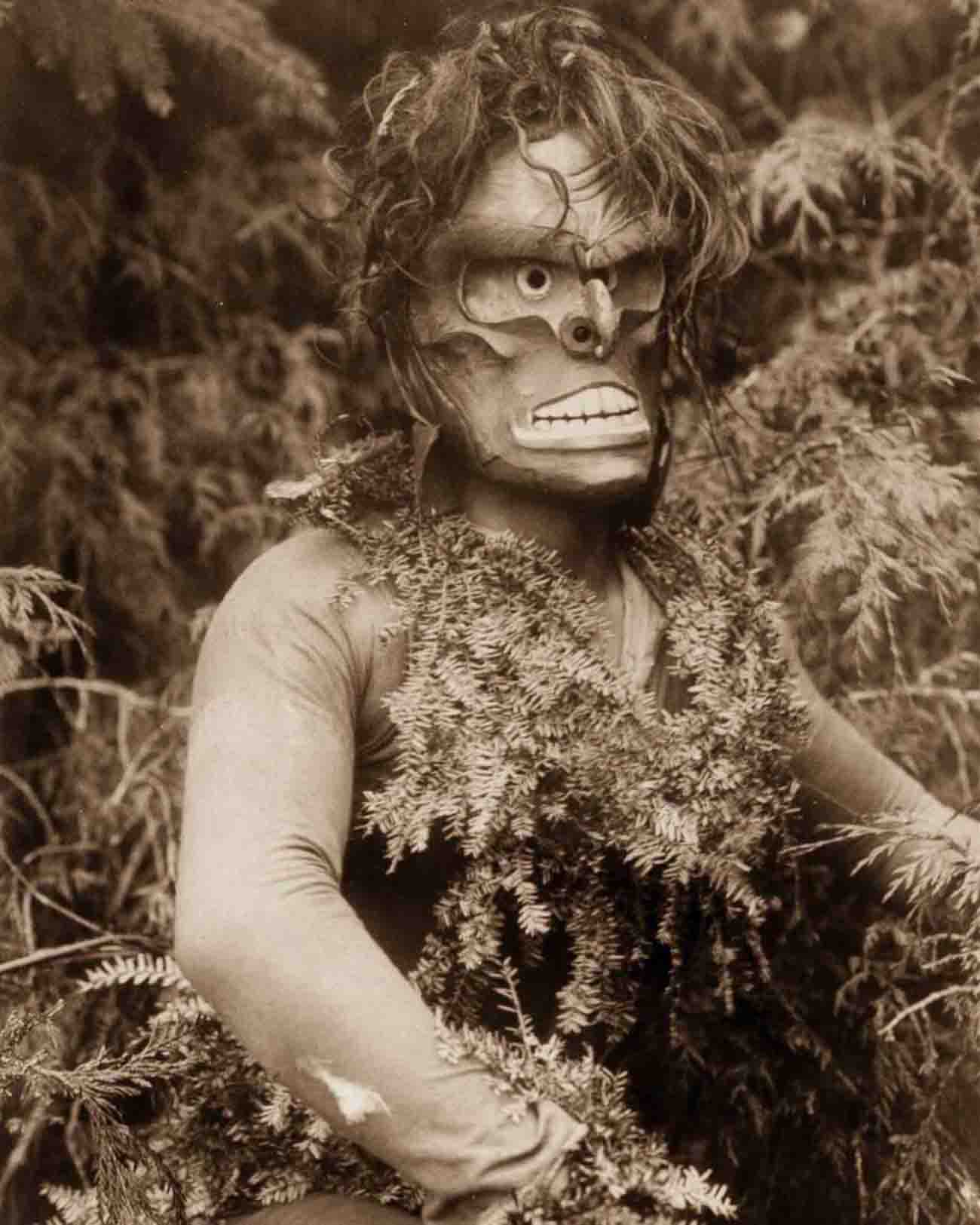

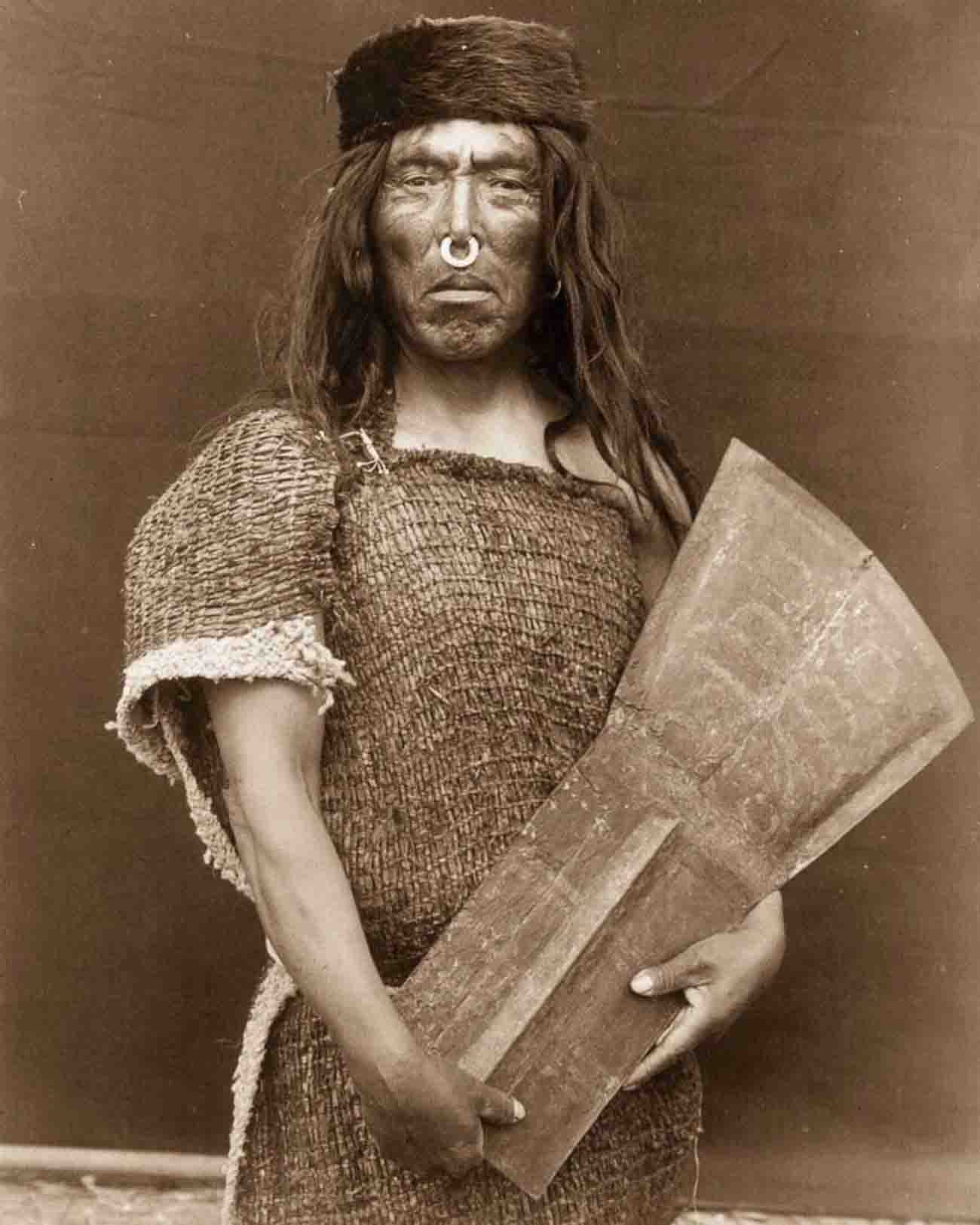

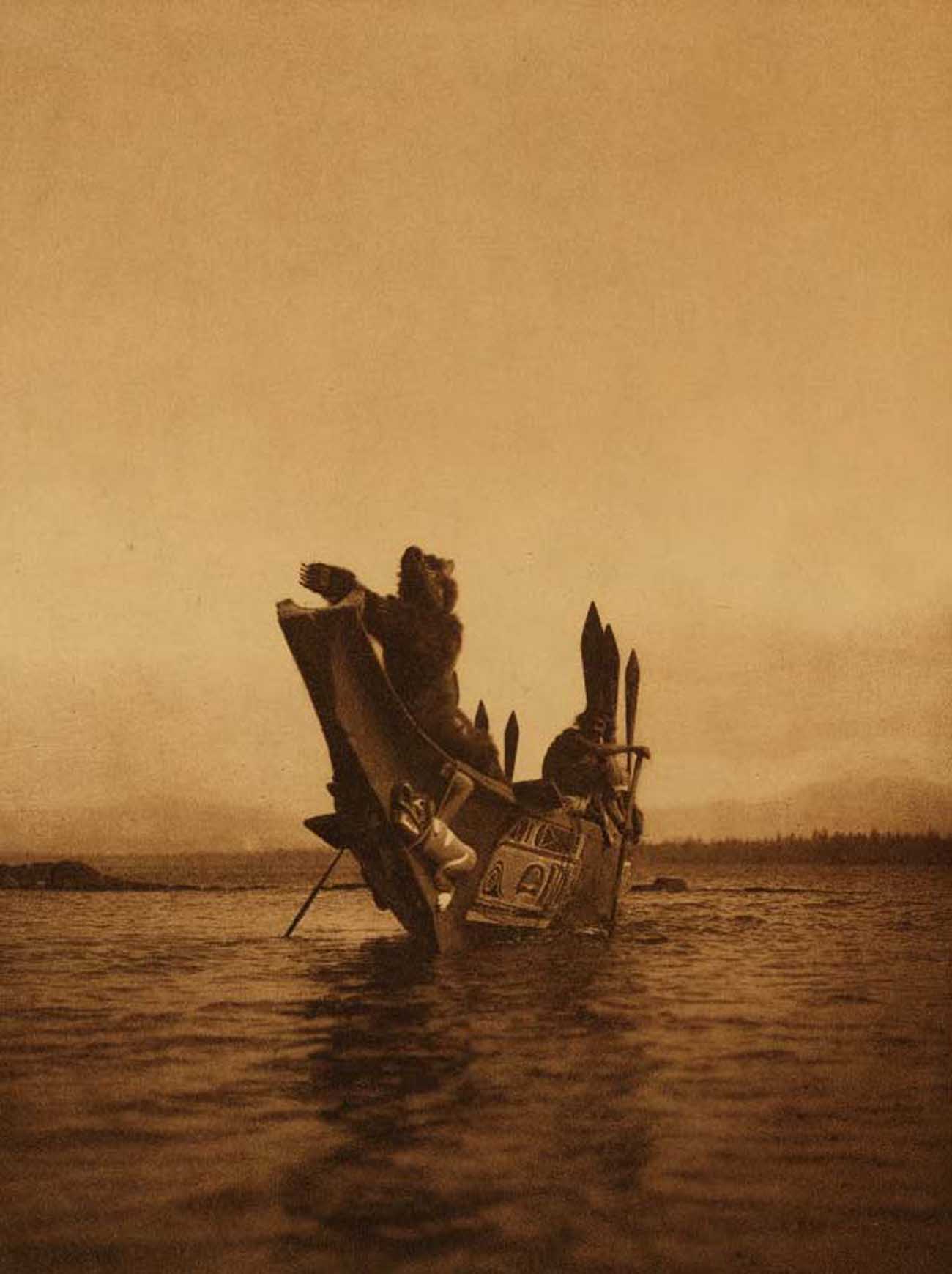

When the Canadian government focused on the assimilation of First Nations, it suppressed potlatch activities. According to William Duncan, in 1875, the potlatch represented “by far the most formidable of all obstacles” to Indians becoming Christians, if not civilized. The Indian Act of 1885 included a provision banning the potlatch and making it illegal to practice. A later amendment expanded the Act to prohibit guests from participating in the potlatch ceremony. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw were too numerous to police, and the government could not enforce the law. Kwakwakaʼwakw arts include totems, masks, textiles, jewelry, and carved objects ranging in size from transformation masks to 40 ft (12 m) high totem poles. The Kwakwakaʼwakw sculpted and carved cedar wood because it was readily available in the native regions. There were bold cuts, a degree of realism, and emphatic use of paints in carving totems. Kwakwakaʼwakw art is strongly influenced by masks, as masks are vital to portray the characters central to Kwakwakawakw dance ceremonies.

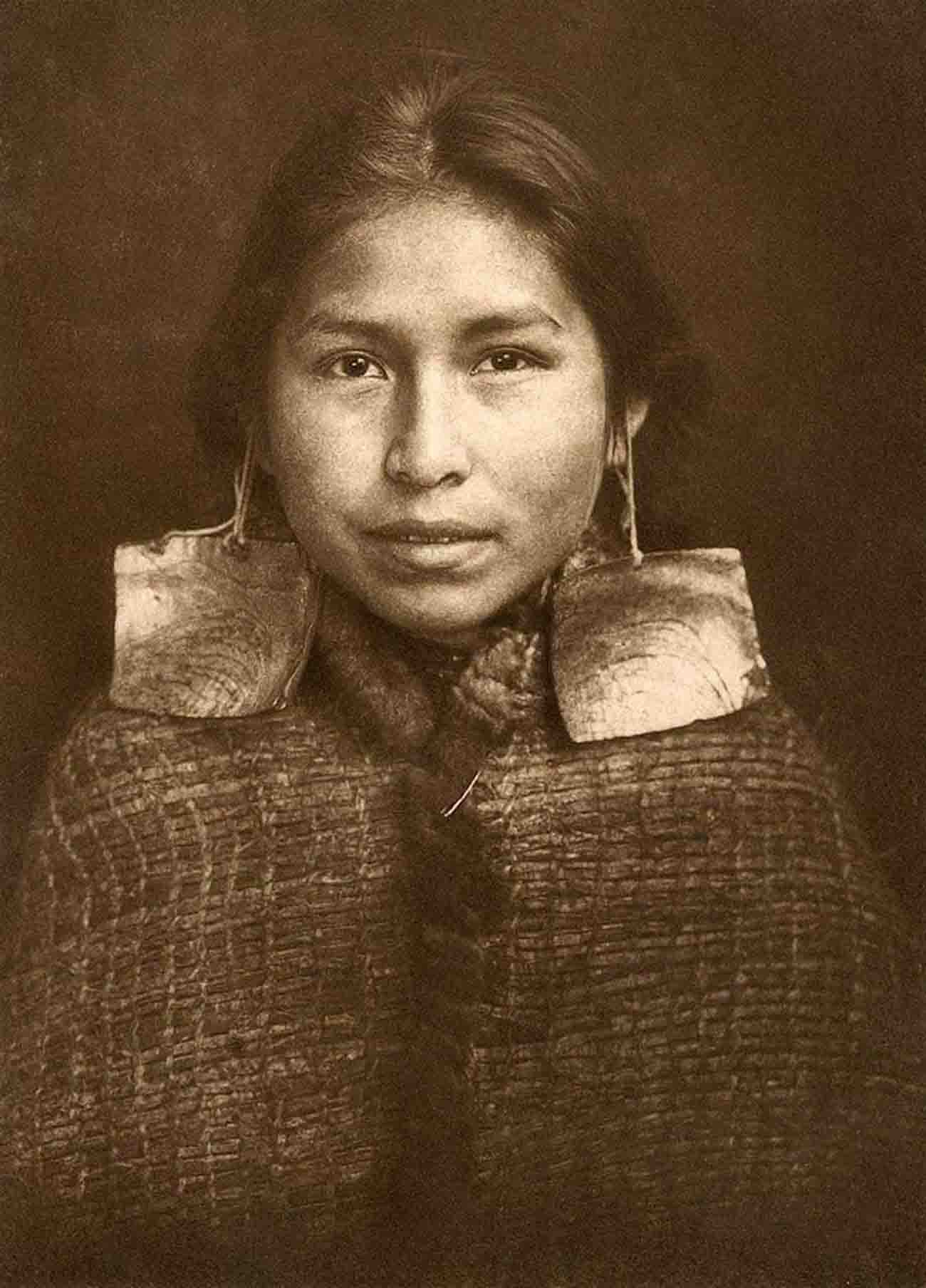

Edward Curtis (1868–1952), a photographer and ethnologist famous for his work with Native Americans, created the photographs of the Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial dress and masks.